Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

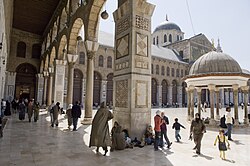

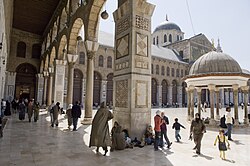

Courtyard

View on WikipediaA courtyard or court is a circumscribed area, often surrounded by a building or complex, that is open to the sky.

Courtyards are common elements in both Western and Eastern building patterns and have been used by both ancient and contemporary architects as a typical and traditional building feature.[1] Such spaces in inns and public buildings were often the primary meeting places for some purposes, leading to the other meanings of court. Both of the words court and yard derive from the same root, meaning an enclosed space. See yard and garden for the relation of this set of words. In universities courtyards are often known as quadrangles.

Historic use

[edit]

Courtyards—private open spaces surrounded by walls or buildings—have been in use in residential architecture for almost as long as people have lived in constructed dwellings. The courtyard house makes its first appearance c. 6400–6000 BC (calibrated), in the Neolithic Yarmukian site at Sha'ar HaGolan, in the central Jordan Valley, on the northern bank of the Yarmouk River, giving the site a special significance in architectural history.[2] Courtyards have historically been used for many purposes including cooking, sleeping, working, playing, gardening, and even places to keep animals.

Before courtyards, open fires were kept burning in a central place within a home, with only a small hole in the ceiling overhead to allow smoke to escape. Over time, these small openings were enlarged and eventually led to the development of the centralized open courtyard we know today. Courtyard homes have been designed and built throughout the world with many variations.

Courtyard homes are more prevalent in temperate climates, as an open central court can be an important aid to cooling house in warm weather.[3] However, courtyard houses have been found in harsher climates as well for centuries. The comforts offered by a courtyard—air, light,[4] privacy, security, and tranquility—are properties nearly universally desired in human housing. Almost all courtyards use natural elements.[5]

Comparison throughout the world

[edit]

Middle East

[edit]Courtyards were widely used in the ancient Middle East.[6] Middle Eastern courtyard houses reflect the nomadic influences of the region. Instead of officially designating rooms for cooking, sleeping, etc., these activities were relocated throughout the year as appropriate to accommodate the changes in temperature and the position of the sun. Often the flat rooftops of these structures were used for sleeping in warm weather. In some Islamic cultures, private courtyards provided the only outdoor space for women to relax unobserved. Convective cooling through transition spaces between multiple-courtyard buildings in the Middle East has also been observed.[3][7]

In c. 2000 BC Ur, two-storey houses were constructed around an open square were built of fired brick. Kitchen, working, and public spaces were located on the ground floor, with private rooms located upstairs.[8]

Europe

[edit]The central uncovered area in a Roman domus was referred to as an atrium. Today, we generally use the term courtyard to refer to such an area, reserving the word atrium to describe a glass-covered courtyard. Roman atrium houses were built side by side along the street. They were one-storey homes without windows that took in light from the entrance and from the central atrium. The hearth, which used to inhabit the centre of the home, was relocated, and the Roman atrium most often contained a central pool used to collect rainwater, called an impluvium. These homes frequently incorporated a second open-air area, the garden, which would be surrounded by Greek-style colonnades, forming a peristyle. This created a colonnaded walkway around the perimeter of the courtyard, which influenced monastic structures centuries later.

The medieval European farmhouse embodies what we think of today as one of the most archetypal examples of a courtyard house—four buildings arranged around a square courtyard with a steep roof covered by thatch. The central courtyard was used for working, gathering, and sometimes keeping small livestock. An elevated walkway frequently ran around two or three sides of the courtyards in the houses. Such structures afforded protection, and could even be made defensible.

China

[edit]

The traditional Chinese courtyard house, (e.g. siheyuan), is an arrangement of several individual houses around a square. Each house belongs to a different family member, and additional houses are created behind this arrangement to accommodate additional family members as needed. The Chinese courtyard is a place of privacy and tranquility, almost always incorporating a garden and water feature. In some cases, houses are constructed with multiple courtyards that increase in privacy as they recede from the street. Strangers would be received in the outermost courtyard, with the innermost ones being reserved for close friends and family members.

In a more contemporary version of the Chinese model, a courtyard can also be used to separate a home into wings; for example, one wing of the house may be for entertaining/dining, and the other wing may be for sleeping/family/privacy. This is exemplified by the Hooper House in Baltimore, Maryland.

United States

[edit]

A courtyard apartment building type appeared in Chicago in the early 1890s and flourished into the 1920s. They are characterized primarily by a low height, a structure along three sides of a rectangular or square lot, and an open court extending perpendicular to the street. The courtyards are generally deeper than they are wide, but many finer ones are wider than they are deep. Influenced by the privacy and domesticity of a standalone house as much as by strict health codes, the architectural style provided outdoor access and ventilation unseen in earlier multi-unit housing in the United States.

Relevance today

[edit]

More and more, architects are investigating ways that courtyards can play a role in the development of today's homes and cities. In densely populated areas, a courtyard in a home can provide privacy for a family, a break from the frantic pace of everyday life, and a safe place for children to play. With space at a premium, architects are experimenting with courtyards as a way to provide outdoor space for small communities of people at a time. A courtyard surrounded by 12 houses, for example, would provide a shared park-like space for those families, who could take pride in ownership of the space. Though this might sound like a modern-day solution to an inner city problem, the grouping of houses around a shared courtyard was common practice among the Incas as far back as the 13th century[citation needed].

In San Francisco, the floor plans of "marina style" houses often include a central patio, a miniature version of an open courtyard, sometimes covered with glass or a translucent material. Central patios provide natural light to common areas and space for potted outdoor plants. In Gilgit/Baltistan, Pakistan, courtyards were traditionally used for public gatherings where village related issues were discussed. These were different from jirgahs, which are a tradition of the tribal regions of Pakistan.

Gallery

[edit]-

Binnenhof, the Hague, Netherlands. It houses the meeting place of both houses of the States General of the Netherlands,

-

Bahia Palace, Marrakesh, Morocco

-

Daisen-in, a sub-temple of Daitoku-ji, one of the five most important Zen temples of Kyoto

-

A courtyard in Rome, Italy

-

Saint-Émilion's Romanesque ruins

-

City Palace, Udaipur, India

-

Tripoli, the Karamanli House

-

Interior of the ING Building, Edmonton, Canada

-

The courtyard and the pool in Rakib-khaaneh mansion in Isfahan, Iran

-

Central patio in Buenos Aires, Antonio Ballvé Penitentiary Museum

-

Courtyard in Essaouira, Morocco

-

Beit Ghazaleh, Aleppo, Syria

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 149.

- ^ Garfinkel Y. 1993. "The Yarmukian Culture in Israel". Paléorient, 19.1:115 – 134.

- ^ a b Ernest, Raha (2011-12-16). "The role of multiple courtyards in the promotion of convective cooling". eprints.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-01-12.

- ^ Reynolds, John S. (2002). Courtyards: Aesthetic, Social, and Thermal Delight. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 26. ISBN 0-471-39884-5. OCLC 46422024.

- ^ Reynolds, John S. (2002). Courtyards: Aesthetic, Social, and Thermal Delight. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 27. ISBN 0-471-39884-5. OCLC 46422024.

- ^ Reynolds, John S. (2002). Courtyards: Aesthetic, Social, and Thermal Delight. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. IX. ISBN 0-471-39884-5. OCLC 46422024.

- ^ Abdulkareem, Haval A. (2016-01-06). "Thermal Comfort through the Microclimates of the Courtyard. A Critical Review of the Middle-eastern Courtyard House as a Climatic Response". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. Urban Planning and Architectural Design for Sustainable Development (UPADSD). 216: 662–674. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.12.054. ISSN 1877-0428.

- ^ Tim McNeese (1999), History of Civilization - The Ancient World, Lorenz Educational Press, p. 10 ISBN 9780787703875

- Atrium: Five Thousand Years of Open Courtyards, by Werner Blaser 1985, Wepf & Co.

- Atrium Buildings: Development and Design, by Richard Saxon 1983, The Architectural Press, London

- A History of Architecture, by Spiro Kostof 1995, The Oxford Press.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Courtyards at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Courtyards at Wikimedia Commons