Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

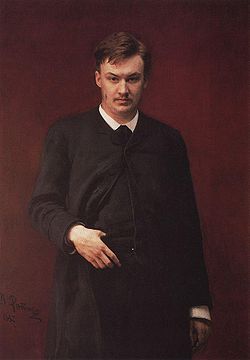

Ilya Repin

View on Wikipedia

Ilya Yefimovich Repin[a] (5 August [O.S. 24 July] 1844 – 29 September 1930) was a Ukrainian-born Russian painter.[b][c] He became one of the most renowned artists in Russia in the 19th century.[7][12][13] His major works include Barge Haulers on the Volga (1873), Religious Procession in Kursk Province (1880–1883), Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan (1885), and Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks (1880–1891). He is also known for the revealing portraits he made of the leading Russian literary and artistic figures of his time, including Mikhail Glinka, Modest Mussorgsky, Pavel Tretyakov, and especially Leo Tolstoy, with whom he had a long friendship.

Key Information

Repin was born and brought up in Chuguev, then part of the Russian Empire. His father had served in an Uhlan regiment in the Russian army and then sold horses.[14] Repin began painting icons at age sixteen. He failed at his first effort to enter the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Saint Petersburg, but went to the city anyway in 1863, audited courses, and won his first prizes in 1869 and 1871. In 1872, after a tour along the Volga River, he presented his drawings at the Academy of Art in St. Petersburg. Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich awarded him a commission for a large scale painting, The Barge Haulers of the Volga, which launched his career. He spent two years in Paris and Normandy, seeing the first Impressionist expositions and learning the techniques of painting in the open air.[15]

He suffered one setback in 1885 when his history portrait of Ivan the Terrible killing his own son in a fit of rage caused a scandal, resulting in the painting being removed from exhibition. But this was followed by a series of major successes and new commissions. In 1898, with his second wife, he built a country house, which he called "The Penates" ('Penaty' in Russian) in the village of Kuokkala, Finland, where they entertained Russian society.[15] The house and garden now constitute the Penaty Memorial Estate and the village and district were renamed to Repino, now a suburban area of Russia's Saint Petersburg.[15]

In 1905, following the repression of street demonstrations by the Imperial government, he quit his teaching position at the Academy of Fine Arts. He welcomed the February Revolution in 1917, but was appalled by the violence and terror unleashed by the Bolsheviks following the October Revolution. Later that year, Finland declared its independence from Russia. Following this event, Repin was unable to travel to St. Petersburg (renamed Leningrad), even for an exhibition of his own works in 1925. Repin died on 29 September 1930, at the age of 86, and was buried at the Penates. His home is now a museum and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[16]

Biography

[edit]Early life and work

[edit]

Ilya Yefimovich Repin was born on 5 August [O.S. 24 July] 1844 in Chuguev, a town in the Kharkov Governorate of the Russian Empire.[17][18] The town, now known by Chuhuiv, is now a city in the Kharkiv Oblast of Ukraine. His father, Yefim Vasilyevich Repin (1804–1894), was a military settler who served in an Uhlan regiment of the Imperial Russian Army.[18] He fought in the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828, the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829, and the Hungarian campaign of 1849. When his father retired from the army in the early 1850s, after 27 years of service, he became an itinerant merchant selling horses.[19] Although some sources referred to Repin as having Cossack or Ukrainian ancestry, he had none; instead, he identified as a Russian born in Little Russia – the name applied to Ukraine at the time.[20] His ancestors were ethnic Russians who served in the streltsy and were sent to Chuguev to assist local Cossacks.[21] Despite this, he felt affinity with both the Cossacks and Ukrainians.[22]

Repin's mother, Tatyana Stepanovna Repina (née Bocharova; 1811–1880), was also the daughter of a soldier. She had family ties to noblemen and officers; the Repins had six children and were moderately well-off.[23][24] He had two younger brothers: one who died at the age of ten, and another named Vasily.[19] Repin spent much of his childhood in the provincial town of Chuguev, located 45 miles (72 km) from Kharkov, the second-largest city in Little Russia.[18]

In 1855, at the age of eleven, he was enrolled at the local school where his mother taught.[25][26] He showed a talent for drawing and painting, and when he was thirteen, his father enrolled him in the workshop of Ivan Bunakov, an icon painter. He restored old icons and painted portraits of local notables. At the age of sixteen, his skill was recognized, and he became a member of an artel, or cooperative of artists, the Society for the Encouragement of Artists, which traveled around Voronezh province to paint icons and wall paintings.[27]

Repin had much higher ambitions. In October 1863, he competed for admission to the Imperial Academy of Arts in the capital, Saint Petersburg. He failed in his first attempt, but persevered, rented a small room in the city, and took courses in academic drawing. In January 1864 he succeeded and was allowed, without fee, to attend classes.[27] His brother Vasily also followed him to Saint Petersburg.[19]

At the academy he met the painter Ivan Kramskoi, who became his professor and mentor.[25] When Kramskoi founded the first independent union of Russian artists, Repin became a member. In 1869, he was awarded a gold medal second-class for his painting Job and His Brothers.[28] He met the influential critic Vladimir Stasov and painted a portrait of Vera Shevtsova, his own future wife.[23]

First success

[edit]-

Early sketch for Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870)

-

Barge Haulers on the Volga, Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg (1870–1873)

-

Early study, Storm on the Volga, State Russian Museum (1873)

-

Resurrection of the Daughter of Jairus (1874)

In 1870, with two other artists, Repin traveled to the Volga River to sketch landscapes and studies of barge haulers (the Repin House in Tolyatti and the Repin Museum on the Volga commemorate this visit). When he returned to Saint Petersburg, the quality of his Volga boatmen drawings won him a commission from Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich for a large scale painting on the subject. The painting, Barge Haulers on the Volga was completed in 1873. The following year, he was awarded a gold medal first-class for his painting The Resurrection of the Daughter of Jairus.[23]

In May 1872, he married Vera Alexeievna Shevtsova (1855–1917).[29] She joined him on his travels, including a trip to Samara, where their first child, Vera, was born. They had three other children; Nadia, Yuri, and Tatyana.[29] The marriage was difficult, as Repin had numerous affairs, while Vera cared for the children. They were married for fifteen years.

In an 1872 letter to Stasov, Repin wrote: "Now it is the peasant who is the judge and so it is necessary to represent his interests. (That is just the thing for me, since I am myself, as you know, a peasant, the son of a retired soldier who served twenty-seven hard years in Nicholas I's army.)"[30] In 1873, Repin traveled to Italy and France with his family. His second daughter, Nadezhda, was born in 1874.[31]

Paris and Normandy

[edit]-

A Novelty Seller in Paris, Tretyakov Gallery (1873)

-

A Paris Cafe, Museum of Avant-Garde Mastery, Moscow (1875)

-

Sadko, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg (1876)

Repin's painting Barge Haulers of the Volga, shown at the Vienna International Exposition, brought him his first International attention. It also earned him a grant from the Academy of Fine Arts which allowed him to make an extended tour of several months to Austria, then Italy, and finally in 1873, to Paris. He rented an apartment in Montmartre at 13 rue Veron, and a small attic studio under a mansard roof at number 31 on the same street.[28]

He remained in Paris for two years. He described his subjects as "the principal types of Parisians, in the most typical settings." He painted the street markets and boulevards of Paris, and especially the varied faces and costumes of the Parisians of every class. His major Russian work created in Paris was Sadko (1876), a mystical allegory of an undersea kingdom, which included elements of Art Nouveau. He gave the young heroine a Russian face, surrounded by a strange and exotic setting. He wrote to his friend the civic Stasov: "This idea describes my present situation, and perhaps, the situation of all of our Russian art".[28] In 1876, his Sadko painting won him a place in the Russian Academy of Fine Arts.

He was in Paris in April 1874, when the First Impressionist Exhibition was held. In 1875, he wrote to Stasov about "The liberty of the "impressionalists", Manet, Monet et the others, and their infantile truthfulness."[28] In 1876, he painted a portrait of his wife Vera in the exact style of Berthe Morisot's portrait by Édouard Manet. as a tribute to Manet and Morisot.[32] Though he admired some impressionist techniques, especially their depictions of light and color, he felt their work lacked moral or social purpose, key factors in his own art.[17]

Following the ideas of the Impressionists, he spent two months at Veules-les-Roses in Normandy, painting landscapes in the open air. In 1874–1876 he contributed to the Salon in Paris.[33] In 1876, he wrote to the secretary of the Russian academy of arts: "You told me not to become "Francified." What are you saying? I dream only of returning to Russia and working seriously. But Paris was of great utility to me, it can't be denied."[34]

Moscow and "The Wanderers" (1876–1885)

[edit]-

Religious Procession in Kursk Province (1880–1883; Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

-

Detail of the Religious Procession in Kursk Province (1881–1883)

-

Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan, Tretyakov Gallery (1885)

-

The Tsarevna Sophia Alekseyevna, Tretyakov Gallery (1879)

-

They Did Not Expect Him, Tretyakov Gallery (1884–1888)

Repin returned to Russia in 1876. His son Yury was born the following year. He moved to Moscow that year, and produced a wide variety of works including portraits of the painters Arkhip Kuindzhi and Ivan Shishkin. He became involved with the "Wanderers", an artistic movement founded in St. Petersburg in 1863. The style of the Wanderers was resolutely realistic, patriotic, and politically engaged, determined to break with classical models and to create a specifically Russian art.[35] It involved not only painters, but sculptors, writers and composers.[33]

Repin created a series of major historical works, including the Religious Procession in Kursk Governorate (1883), which was presented at the 12th annual exposition of the Wanderers. It was notable both for its extraordinary crowd of realistic figures, including surly policemen, weary monks, children and beggars, each expressing a vivid personality. He also experimented with outdoor sunlight effects, apparently influenced by the impressionists and his outdoor studies in France.[35] His next major work of this period was Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan. This painting, depicting the tsar, his face full of horror, just after he has killed his son with his sceptre in a demented rage. It caused a scandal. Some critics saw it as a veiled criticism of Tsar Alexander III, who had brutally suppressed the opposition after a failed assassination attempt. It was also attacked by the more aesthetic faction of the Wanderers, who considered it overly sensationalist. It was vandalised twice and was finally, at the tsar's request, removed from view. The tsar reconsidered his decision, and the painting was finally put back on view.[36]

The portrait of Tsarevna Sophia Alekseyevna is one of his most tragic historical works. It depicts the daughter of Tsar Alexis who became regent of Russia after the death of her father, but then was deposed from power in 1689 and locked away in a convent by her half-brother, Peter the Great. The painting captures her fury as she realises her future life.[37]

They Did Not Expect Him (1884–1888) is a notable and subtle historical work of the period, depicting a young man, a former narodnik or revolutionary, emaciated and frail from prison and exile, returning unexpectedly to his family. The story is told by the different expressions on the faces of his family and small details, such as the portraits of Tsar Alexander III and of favourite Russian poets on the wall.[38]

Repin and Tolstoy

[edit]-

Portrait of Tolstoy (1887)

-

Tolstoy reading under a tree in the forest, Tretyakov Gallery Moscow (1891)

-

Tolstoy writing at Yasnaya Polyana, Pushkin House (1891)

-

Tolstoy barefoot, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg (1901)

-

Portrait of Tolstoy shortly before his death (1908)

In 1880, Leo Tolstoy came to Repin's small studio on Bolshoi Trubny street in Moscow to introduce himself. This developed into a friendship between the 36-year-old painter and the 52-year-old writer that lasted thirty years until Tolstoy's death in 1910. Repin regularly visited Tolstoy at his Moscow residence, and his country estate at Yasnaya Polyana. He painted a series of portraits of Tolstoy in peasant dress, working and reading under a tree at Yasnaya Polyana. Tolstoy wrote of an 1887 visit by Repin: "Repin came to see me and painted a fine portrait. I appreciate him more and more; he is lively person, approaching the light to which all of us aspire, including us poor sinners."[38] His last trip to see Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana was in 1907, when Tolstoy was 79. Despite his age, Tolstoy went horseback riding with Repin, ploughed fields, cleared paths of brush and hiked through the countryside for nine hours, all the while discussing philosophy and morals. Repin's portraits of Tolstoy in country dress were widely exhibited, and helped build Tolstoy's legendary image.[38]

Repin and Russian composers

[edit]-

Anton Rubinstein, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (1881)

-

Portrait of M. P. Mussorgsky, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (1881)

-

Mikhail Glinka composing the opera Ruslan and Ludmilla, painted thirty years after Glinka's death (1887)

-

Alexander Glazunov, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg (1887)

-

Portrait of composer and chemist Alexander Borodin (1888)

In addition to his portraits of Tolstoy and Russian writers, Repin painted portraits of the major Russian composers of his time, His images, like his paintings of Tolstoy and other writers, became an integral part of the image of these composers. His portrait of Modest Moussorgsky was particularly famous. The composer suffered from alcoholism and depression. Repin painted him in four sittings, beginning four days before his death. When Moussorgsky died, Repin used the proceeds of the sale of the painting to erect a monument to the composer.[39]

His portrait of Mikhail Glinka, composer of the opera Ruslan and Ludmilla (1887) was an unusual work for Repin. The portrait was painted after Glinka's death (Repin never met him), and was based on drawings and recollections of others. Other composers painted by Repin included Alexander Glazunov who had just completed Borodin's opera "Prince Igor", and Anton Rubinstein the founder of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory of Music.[39]

His third daughter, Tatyana, was born in 1880.[33] He frequented the art circle of Savva Mamontov, which gathered at Abramtsevo, his estate near Moscow. Here Repin met many of the leading painters of the day, including Vasily Polenov, Valentin Serov, and Mikhail Vrubel.[40] In 1882 he and Vera divorced; they maintained a friendly relationship afterwards.[41]

Repin's contemporaries often commented on his special ability of capturing peasant life in his works. In an 1876 letter to Stasov, Kramskoi wrote: "Repin is capable of depicting the Russian peasant exactly as he is. I know many artists who have painted peasants, some of them very well, but none of them ever came close to what Repin does."[42] Leo Tolstoy later stated that Repin "depicts the life of the people much better than any other Russian artist."[17] He was praised for his ability to reproduce human life with powerful and vivid force.[42]

Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks

[edit]-

Preparatory sketch, Tretyakov Gallery (1878)

-

Preliminary version detail (1880–1890)

-

Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed IV, State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg (1880–1891)

In 1883, he traveled around Western Europe with Vladimir Stasov. Repin's painting Religious Procession in Kursk Province was shown at the eleventh Itinerants' Society Exhibition. In that year, he painted The Wall of Pere Lachaise Cemetery Commemorating the Paris Commune. In 1886, he traveled to the Crimea with Arkhip Kuindzhi, and produced drawings and sketches on biblical subjects.

In 1887, he visited Austria, Italy, and Germany, and retired from the board of the Wanderers, painted two portraits of Leo Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana and painted Alexander Pushkin on the Shore of the Black Sea (in collaboration with Ivan Aivazovsky).[43] In 1888, he traveled to southern Russia and the Caucasus, where he did sketches and studies of descendants of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. Throughout the 1870s to 1880s, he visited Chuguyev and gathered materials for his future works. There, he painted his Archdeacon.[44]

Many of Repin's finest portraits were produced in the 1880s. Through the presentation of real faces, these portraits express the rich, tragical, and hopeful spirit of the period. His portraits of Aleksey Pisemsky (1880), Modest Mussorgsky (1881), and others created throughout the decade have become familiar to whole generations of Russians. Each is completely lifelike, conveying the transient, changeable nature of the sitter's state of mind. They give an intense embodiment of both the physical and spiritual life of the people who sat for him.[45]

In 1887 he was separated from his wife Vera. He visited Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana, and painted his portrait, and then took a long trip along the Volga and the Don, to the Cossack regions. This trip gave him material for his most famous historical work, Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. The painting depicts an apocryphal event in 1678, when a group of cossacks supposedly amused themselves by drafting a highly insulting letter to the Turkish sultan, addressing him as "The Grand Imbecile".[46] Repin worked on this painting periodically between 1880 and 1891, creating an extraordinary ensemble of expressive faces. Most of the models were faculty members from the Academy of Arts, and had a variety of nationalities, including Russians, Ukrainians, a Cossack student, Greeks, and Poles. The Cossack with a yellow hat, at the top right and almost hidden by Taras Bulba, is Fyodor Stravinsky, an opera singer with the Mariinsky Theatre, of Polish descent, and the father of the composer Igor Stravinsky.[47][48] The central figure in the painting was inspired by a legendary Cossack leader Ivan Sirko, modeled by Russian General Mikhail Dragomirov.[49] The finished work was so popular that he painted a second version.[50]

-

The Wall of Pere Lachaise Cemetery Commemorating the Paris Commune (1883) (Tretyakov Gallery)

-

Tsar Alexander III Receives Local Government Officials at Petrovsky Palace (1886)

-

Tsar Nicholas II (1896) by Repin

In 1890, he was given a government commission to work on the creation of a new statute for the Academy of Arts. In 1891 he resigned from the Wanderers in protest against a new statute that restricted the rights of young artists. An exhibition of works by Repin and Shishkin was held in the Academy of Arts, including Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. In 1892 he held a one-man exhibition at the History Museum in Moscow. In 1893 he visited academic art schools in Warsaw, Kraków, Munich, Vienna, and Paris to observe and study teaching methods. He spent the winter in Italy and published his essays Letters on Art.[51]

In 1894, he began teaching a class at the Higher Art School attached to the Academy of Arts, a position he held, off and on, until 1907.[52] In 1895 he painted portraits of Emperor Nicholas II, and Princess Maria Tenisheva. In 1896, he attended the All-Russian Exhibition in Nizhny Novgorod. His paintings were exhibited in Saint Petersburg, at the Exhibition of Works of Creative Art. His paintings from this year included The Duel and Don Juan and Dona Anna. In 1897, he rejoined the Wanderers, and was appointed rector of the Higher Artistic School for a year. In 1898 he traveled to the Holy Land, and painted the icon Carrying the Cross for the Russian Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Jerusalem. After returning to Russia, he attended Pavel Tretyakov's funeral. In 1899 he joined the editorial board of the magazine World of Art, but soon quit.

Move to Finland (1890)

[edit]-

What Freedom! (1903)

-

The Penaty Memorial Estate, originally in Finland, now in Repino, Saint Petersburg

In 1890, Repin met Natalia Nordman (1863–1914), who became his common-law wife. She was the daughter of an admiral, a writer and feminist, an activist for the improvement of working conditions. She advocated a simple life close to nature. In 1899, he acquired land near a village of Kuokkala, about forty kilometres north of St. Petersburg, and they built what is the Penaty Memorial Estate, a country house, which became his home for the next thirty years. It was located in the Grand Duchy of Finland, then part of the Russian Empire, about an hour by train from St. Petersburg. At first he used it only as a summer house, but after he resigned from the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts in 1907, it became his full-time home and studio.[53][54][55] It was a rather eccentric estate, including a studio covered with a pyramidal lantern roof, a landscape garden with a "Pushkin alley" of trees, a multicoloured music kiosk in the Egyptian style, and a telescope overlooking the Gulf of Finland. He hosted vegetarian breakfasts for his guests (a practice he adapted from Tolstoy), and very elaborate receptions on Wednesdays. His Wednesday guests included the opera singer Chaliapin, the writer Maxim Gorky, the composer Alexander Glazunov the writer Aleksandr Kuprin; artists Vasily Polenov, Isaak Brodsky and Nicolai Fechin as well as poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, philosopher Vasily Rozanov and scientist Vladimir Bekhterev. [53][54][56][self-published source?]

In 1900, he took Nordman to the World Exhibition in Paris, where he served as a painting judge. They visited Munich, the Tyrol, and Prague, His painting Get Thee Behind Me, Satan! was shown at the 29th Exhibition of the Wanderers. In 1901, he received from the tsar one of his largest commissions, portraits of all sixty members of State Council. He proceeded with the help of photographs and the aid of two of his students.[57] One of the subjects was Alexander Kerensky, the Russian president before the Bolshevik seizure of power.[54] In addition to his government commissions, he found time for a light work on an entirely different theme; a painting in 1902–1903 called What Freedom! depicting two students dancing in the waves at the beach after completing their examinations.[58][54]

Revolution and disillusion (1900–1905)

[edit]-

Natalia Nordman in a Tyrolese Hat (1900)

-

In the Sunlight: Portrait of Nadezhda Repina (1900)

-

Ceremonial Sitting of the State Council on 7 May 1901 Marking the Centenary of its Foundation (1902–1903). Repin was a pioneer in photographic realism.

-

Demonstration on 17 October 1905 (1905)

The repression of popular demonstrations in front of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg in 1905 disillusioned Repin. He called 1905 "the year of disaster and shame". He resigned from his teaching post at the Academy of Fine Arts, and concentrated on painting. The movements toward democracy in the early 20th century inspired Repin, he joined the Constitutional Democratic Party, was offered the rank of Councillor of State, and was invited to take a seat in the Duma, the national assembly. He made a colourful painting of the celebration of the new Russian Constitution of 1905. Later, he painted the portrait of the newly-elected Russian President, Alexander Kerensky.

Repin concentrated on writing his memoirs, which he finished in 1915. He visited St. Peterburg to see expositions, including a 1909 show of works by the modernist Wassily Kandinsky. Repin was not impressed; he described it as "the swamps of artistic corruption".[59]

He visited Munich, the Tyrol, and Prague, and painted Natalia Nordman in a Tyrolese Hat and In the Sunlight: Portrait of Nadezhda Repina. In 1901, he was awarded the Legion of Honor. In 1902–1903, his works included the paintings Ceremonial Meeting of the State Council and What a Freedom!, over forty portrait studies, and portraits of Sergei Witte and Vyacheslav von Plehve.[54]

In 1904, he gave a speech at a memorial gathering for the artist Vasily Vereshchagin. He painted a portrait of the writer Leonid Andreyev and his work The Death of the Cossack Squadron Commander Zinovyev. He made sketches depicting government troops opening fire on a peaceful demonstration on 9 December 1905.[54] During 1905 Repin participated in many protests against bloodshed and tsarist repressions, and tried to convey his impressions of these emotionally and politically charged events in his paintings.[60]

He also did sketches for portraits of Maxim Gorky and Vladimir Stasov and two portraits of Natalia Nordman. In 1907, he resigned from the Academy of Arts, visited Chuguyev and the Crimea, and wrote reminiscences of Vladimir Stasov. In 1908, he publicly denounced capital punishment in Russia. He illustrated Leonid Andreyev's story The Seven Who Were Hanged, and his painting The Cossacks from the Black Sea Coast was exhibited at the Itinerants' Society Exhibition. In 1909, he painted Gogol Burning the Manuscript of the Second Part of Dead Souls, and in 1910, portraits of Pyotr Stolypin, and the children's writer and poet Korney Chukovsky.[54]

War, the Bolshevik Revolution and later years (1917–1930)

[edit]-

Repin in his studio at the Penaty Memorial Estate (1914)

-

Drawing of a Red Army soldier stealing bread from a child (1918)

-

The Gopak, the last painting of Repin (1926–30), painted on linoleum, because he could not get a canvas large enough

-

The tomb of Repin at the Penaty Memorial Estate

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 brought a series of setbacks and tragedies to Repin. His wife became ill with tuberculosis, and departed for treatment in Locarno, Switzerland. She refused assistance from her family and died in Switzerland in 1914. Then, following the October 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Finland, including Rupin's home, "The Penates" ('Penaty' in Russian), declared its independence from Russia. The border was closed, and Repin refused to return to Russia. He turned to Finland for new clients, painting a large group portrait of notable Finnish leaders and artists, including the architect Eliel Saarinen, the composer Jean Sibelius, and the future Finnish president, Carl Gustav Mannerheim. Repin included the back of his own head in the painting.[61]

In 1916, Repin worked on his book of reminiscences, Far and Near, with the assistance of Korney Chukovsky. He welcomed the early phases of the Russian Revolution, namely the February Revolution of February 1917. However, he was hostile to the Bolsheviks and was appalled by their rise to power in the October Revolution and the violence and terror they unleashed thereafter. In 1919, he donated his collection of works by Russian artists and his own works to the Finnish National Gallery in Helsinki, and in 1920, honorary celebrations of Repin were held by artistic circles in Finland. In 1921–1922, he painted The Ascent of Elijah the Prophet and Christ and Mary Magdalene (The Morning of the Resurrection).[62]

Repin was so hostile to the new Soviet government, that he even lashed out at their spelling reform. Specifically, he objected to writing his last name "Рѣпинъ" (Repin) under the new rules, which made it "Репин", as the elimination of the letter "ѣ" led many people to incorrectly spell his name as Ryopin.[63]

After end of the war in 1918, Repin could travel again. In 1923, Repin held a one-man exhibition in Prague. Celebrations were given in 1924 in Kuokkala to mark Repin's 80th birthday, and an exhibition of his works was held in Moscow. In 1925, a jubilee exhibition of his works was held in the Russian Museum in Leningrad (renamed St Petersburg-Petrograd). The new Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, sent a delegation of Soviet artists, including a former student of Repin, Isaak Brodsky, to persuade Repin to return to St. Petersburg, and to give up his residence in Finland. But Repin did not want to be under the thumb of Stalin, and refused, though he donated three sketches devoted to the Revolution of 1905 and the portrait of Alexander Kerensky to the Museum of the Revolution of 1905.[64] In 1928–1929, while still in Finland, he continued working on the painting The Hopak Dance (The Zaporozhye Cossacks Dancing), begun in 1926, which was his final work. It portrays Repin's admiration of Ukraine and its culture. Repin painted it with oil on linoleum, because he could not get a canvas large enough.[65]

Repin died in 1930, and was buried at The Penates ('Penaty').[66] In one of his last letters he wrote: "kind, dear compatriots [...] I ask you to believe in the sense of my devotion and endless regret that I can't move to live in a sweet, joyful Ukraine [...] Loving you from the childhood, Ilya Repin".[44] After the Winter War in 1939, the territory of Kuokkala was annexed by the Soviet Union. In 1948, despite Repin's hostility towards Bolshevism, it was renamed Repino in his honor. The Penates became a museum in 1940,[17] and is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Portraits

[edit]-

The Dragonfly, Repin's daughter Vera, aged twelve (1884)

-

Sketch for Portrait of Sergei Witte, the first prime minister of the new Russian government (1903)

-

Portrait of Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov, founder of the Tretyakov Gallery

-

Portrait of Sophie Menter, pianist and professor of music at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory

-

Painter Elizaveta Zvantseva, Ateneum Gallery, Helsinki (1889)

-

General and military writer Mikhail Dragomirov (1889)

-

General Dragamirov was also the model for a Cossack leader in "Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks"

Repin particularly excelled at portrait painting. He produced more than three hundred portraits in his career. He painted most of the notable political figures, writers and composers of his time. One exception was Dostoevsky, whose mysticism Repin did not appreciate at all. He preceded each portrait with six or seven sketches. He had to persuade a reluctant Tolstoy to be portrayed working in a field with bare feet, as he usually did.

Drawings and sketches

[edit]-

Sketch for Religious Procession in Kursk (1878)

-

Pencil sketch of the composer Alexander Glazunov (1880s)

-

Drawing for Nevsky Prospect in St. Petersburg, graphite pencil on paper (1887)

-

The actress Eleanor Duse by Repin, charcoal on paper (1891)

-

Study for portrait of the art patroness Princess Maria Tenisheva (1896)

With some of his paintings, Repin made one hundred or more preliminary sketches. He began his works with sketches in pencil or charcoal, using lines and cross-hatching. Often he would rub the drawing with his finger or an eraser to get the precise shading that he desired. He sometimes used drawings or paintings of his children to experiment with different points of view. For his large paintings, he made very detailed studies, experimenting with the composition and judging the overall impression.

Genre painting

[edit]-

Repin's family on a turf bench (1876)

-

Seeing off a Recruit, State Russian Museum (1879)

No Russian painter of the 19th or 20th century was more skilled at genre painting, portraying scenes of daily life in a sympathetic and perceptive way, giving each character a distinct purpose and personality. His works ranged from domestic scenes to small dramas, such as policemen arresting a young militant for distributing revolutionary tracts.

Style and technique

[edit]

Repin persistently searched for new techniques and content to give his work more fullness and depth.[67] Repin had a set of favorite subjects, and a limited circle of people whose portraits he painted. But he had a deep sense of purpose in his aesthetics, and had the great artistic gift to sense the spirit of the age and its reflection in the lives and characters of individuals.[68] Repin's search for truth and for an ideal led him in various directions artistically, influenced by hidden aspects of social and spiritual experiences as well as national culture. Like most Russian realists of his times, Repin often based his works on dramatic conflicts, drawn from contemporary life or history. He also used mythological images with a strong sense of purpose; some of his religious paintings are among his greatest.[14]

His method was the reverse of the general approach of impressionism. He produced works slowly and carefully. They were the result of close and detailed study. He was never satisfied with his works, and often painted multiple versions, years apart. He also changed and adjusted his methods constantly in order to obtain more effective arrangement, grouping and coloristic power.[69] Repin's style of portraiture was unique, but owed something to the influence of Édouard Manet and Diego Velázquez.[57]

Legacy

[edit]Repin was the first Russian artist to achieve European fame using specifically Russian themes.[17] His 1873 painting Barge Haulers on the Volga, radically different from previous Russian paintings, made him the leader of a new movement of critical realism in Russian art.[70] He chose nature and character over academic formalism. The triumph of this work was widespread, and it was praised by contemporaries like Vladimir Stasov and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The paintings show his feeling of personal responsibility for the hard life of the common people and the destiny of Russia.[67]

On 5 August 2009, Google celebrated Ilya Repin's Birthday with a doodle.[71]

In a 2017 VTsIOM poll, Repin ranked third as the most favorite artist of Russians, with 16% of respondents naming him as their favorite, behind Ivan Aivazovsky (27%) and Ivan Shishkin (26%).[72][73][74]

Gallery

[edit]- Paintings

-

Slavic Composers (1871)

-

Ukrainian Woman by Repin (1876)

-

Ukrainian traditional peasant house (1880)

-

The Surgeon Evgeny Vasilyevich Pavlov in the Operating Theater (1888)

-

Portrait of Composer César Antonovich Cui (1890)

-

Neapolitan Woman (1894)

-

Portrait of Countess Natalia Petrovna Golovina (1896)

-

The Blonde Woman (1898, portrait of Tevashova)

-

Gogol burning the manuscript of the second part of "Dead Souls" (1909)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /iːljə ˈrɛpɪn/;[2] also spelled Riepin or Rjepin; Russian: Илья Ефимович Репин, pronounced [ˈrʲepʲɪn], pre-reform spelling: Илья Ефимовичъ Рѣпинъ; Ukrainian: Ілля Юхимович Рєпін/Ріпин, romanized: Illia Yukhymovych Riepin/Ripyn;[3] Finnish: Ilja Jefimovitš Repin.

- ^ Attributed to the following sources:[4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

- ^ Repin spoke both Russian and Ukrainian fluently, although he considered himself a Russian.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ Moskvinov, V. N. (1955). Репин в Москве. Moscow: Государственное издательство культурно-просветительской литературы. p. 32.

- ^ Kaltenbach, G. E. (1934). Dictionary of Pronunciation of Artists' Names with Their Schools and Dates: For American Readers and Students. Art Institute of Chicago. p. 56.

- ^ "Спецпроєкт "Справжні". Ілля Ріпин: художник, якого намагається привласнити росія - Фільтр". Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Iovleva, L. I. (2003). "Repin, Il'ya". Grove Art Online. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t071521. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4.

Russian of Ukrainian birth

- ^ "Repin, Ilya Efimovich", Benezit Dictionary of Artists, Oxford University Press, 31 October 2011, doi:10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.b00151213, ISBN 978-0-19-977378-7, retrieved 19 January 2023,

Ukrainian, 19th–20th century, male. Active in Finland from 1917. ... Ilya Efimovich Repin was the son of a soldier-settler from the Russian Army. In later life he would draw on his birthplace for the subject matter in works such as The Zaporozhe Cossacks Writing a Reply to the Turkish Sultan.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ "ULAN Full Record Display: Repin, J. J. (Russian painter, 1844-1930)". Union List of Artist Names (Getty Research). Retrieved 19 January 2023.

Nationalities: Russian (preferred) / Ukrainian

- ^ a b Chilvers, Ian (2015a). "Repin, Ilya". The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-178276-3.

The most famous Russian painter of his day and a central figure in his country's cultural life.

- ^ Chilvers, Ian; Glaves-Smith, John (2015b). "Repin, Ilya". A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-179222-9.

- ^ Jackson, David (1 January 2003). "Repin, Ilya". The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866203-7.

- ^ Chilvers 2004.

- ^ Lang, Walther K. (2002). "The Legendary Cossacks: Anarchy and Nationalism in the Conceptions of Ilya Repin and Nikolai Gogol". Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. 1 (1).

Though Ilya Repin was born and brought up in the Ukraine and spoke fluent Ukrainian, he considered himself a Russian.

- ^ Leigh 2020, p. 221.

- ^ Valkenier, Bale & Nutt 1990, p. xiii, Ilya Repin was Russia's foremost painter of the late nineteenth century. He was the stellar figure of Russian realism.

- ^ a b Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, p. 15 (in French)

- ^ Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, pp. 15-17 (in French)

- ^ a b c d e Chilvers 2004, p. 588.

- ^ a b c Valkenier, Bale & Nutt 1990, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Valkenier, Bale & Nutt 1990, p. 6.

- ^ Valkenier, Bale & Nutt 1990, p. 10, "Although Repin was sometimes credited with Cossack or Ukrainian ancestry, he had neither. He considered himself a Russian born in Little Russia".

- ^ Valkenier, Bale & Nutt 1990, p. 10, "His forebears were Russians who served in the Moscow elite corps (the Streltsy) and had been sent down to Chuguev in 1639 to strengthen some Cossacks who had transferred their loyalty to the tsar".

- ^ Valkenier, Bale & Nutt 1990, p. 10, "Though ethnically a Russian, Repin nevertheless felt affinity with the Cossacks and Ukrainians".

- ^ a b c Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 181.

- ^ Buchastaya S. I., Sabodash E. N., Shevchenko O. A. (2014). New findings on I. Y. Repin's genealogy and a new view on the artist's origin Archived 9 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine article from the Contemporary Issues of Local and World History magazine at the I. Y. Repin's Memorial Art Museum website, pp. 183—187 (in Russian) ISSN 2077-7280

- ^ a b Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, p. 14 (in French)

- ^ a b Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Pommerau, Claude (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, p. 14 (in French)

- ^ a b c d Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021 (in French), p. 34

- ^ a b Leigh 2020, p. 226.

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021 (in French), p. 38

- ^ a b Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, pp. 40–43 (in French).

- ^ Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, pp. 28 (in French).

- ^ Ilya Repin-Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, p. 50 (in French).

- ^ a b c Ilya Repin-Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, p. 23 (in French)

- ^ a b Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, pp. 52-55 (in French)

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 25.

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 130.

- ^ a b Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 183–184.

- ^ a b "Шукач | Мемориальный музей - усадьба И.Е.Репина в Чугуеве". shukach.com. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 78.

- ^ Waugh, Daniel Clarke (1978). The Great Turkes Defiance: On the History of the Apocryphal Correspondence of Ottoman Sultan in its Muscovite and Russian Variants. Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Publishers. ISBN 9780089357561 an Waugh, Daniel Clarke (1978). The Great Turkes Defiance: On the History of the Apocryphal Correspondence of Ottoman Sultan in its Muscovite and Russian Variants. Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Publishers. ISBN 9780089357561

- ^ "Корреспондент: Веселые запорожцы. История создания картины Запорожцы пишут письмо турецкому султану - архив". korrespondent.net. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "Запорожцы пишут письмо турецкому султану — bubelo.in.ua".

- ^ Prymak 2013, p. 9.

- ^ Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, pp. 26-27 (in French)

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Bolton 2010, p. 115.

- ^ a b Il1901ya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, p 60-63 (in French)

- ^ a b c d e f g Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 187–189.

- ^ Apresyan, A. (25 January 2020). "5 eccentricities of great Russian painters". Russia Beyond. Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Daniel Coenn (28 July 2013). Repin: Drawings. Lulu.com. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-304-27417-5.[self-published source]

- ^ a b Leek 2005, p. 63.

- ^ Il1901ya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, p 16-17 (in French)

- ^ Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, p 17 (in French)

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 121.

- ^ Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, p 64 (in French)

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 190–191.

- ^ "9 цитат из писем Ильи Репина • Arzamas". Arzamas. 13 March 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Ilya Repin- Peindre l'âme Russe, Claude Pommereau (editor), Beaux Arts Editions, Paris, October 2021, p 65 (in French)

- ^ Кириллина Е. Репин в «Пенатах». Л., 1977, с. 198.

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 191.

- ^ a b Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 21.

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 13.

- ^ Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 30.

- ^ Bolton 2010, p. 114.

- ^ Ilya Repin's Birthday, retrieved 9 August 2023

- ^ "Айвазовский – к 200-летию!". wciom.ru (in Russian). Russian Public Opinion Research Center. 28 July 2017. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Poll reveals Russians enjoy Aivazovsky's paintings more than other artists' works". TASS. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Самым известным среди россиян живописцем оказался Иван Шишкин" (in Russian). Interfax. 28 July 2017. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chilvers, Ian (2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860476-1.

- Bolton, Roy (2010). Views of Russia & Russian Works on Paper. Sphinx Books. ISBN 978-1-907200-05-2.

- Leek, Peter (2005). Russian Painting. Parkstone Press. ISBN 978-1-85995-939-8.

- Leigh, Allison (17 September 2020). "Ilia Repin: On Masculine Vulnerability". Picturing Russia's Men: Masculinity and Modernity in Nineteenth-Century Painting. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-5013-4181-6.

- Sternine, Grigori; Kirillina, Elena (2011). Ilya Repin. Parkstone Press. ISBN 978-1-78042-733-1.

- Prymak, Thomas M. (2013). "A Painter from Ukraine: Ilya Repin". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 55 (1–2): 19–43. doi:10.1080/00085006.2013.11092725.

- Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl; Bale, Chris; Nutt, Tim (1990). Ilya Repin and the World of Russian Art. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-06964-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Parker, Fan; Stephen Jan Parker (1980). Russia on Canvas: Ilya Repin. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00252-2.

- Sternin, Grigory (1985). Ilya Repin: Painting Graphic Arts. Leningrad: Auroras.

- Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1990). Ilya Repin and the World of Russian Art. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-06964-2.

- Marcadé, Valentine (1990). Art d'Ukraine. Lausanne: L'Age d'Homme. ISBN 978-2-8251-0031-8.

- Jackson, David, The Russian Vision: The Art of Ilya Repin (Schoten, Belgium, 2006) ISBN 9085860016

- Karageorgevich, Prince Bojidar, "Professor Repin," in the Magazine of Art, xxiii. p. 783 (1899)

- Prymak, Thomas M., "Message to Mehmed: Repin Creates his Zaporozhian Cossacks," in his Ukraine, the Middle East, and the West (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2021), pp. 173–200.

- Шишанов, В.А. «Ниспровержение на пьедестал»: Илья Репин в советской печати 1920–1930-х годов / В.А. Шишанов // Архип Куинджи и его роль в развитии художественного процесса в ХХ веке. Илья Репин в контексте русского и европейского искусства. Василий Дмитриевич Поленов и русская художественная культура второй половины XIX – первых десятилетий XX века : материалы научных конференций. – М. : Гос. Третьяковская галерея, 2020. – С. 189–206.

External links

[edit]- Ilya Repin at the Russian Academy of Arts' official website (in Russian)

- Ilya Repin at the Web Gallery of Art

Ilya Repin

View on GrokipediaIlya Yefimovich Repin (5 August [O.S. 24 July] 1844 – 29 September 1930) was a Russian realist painter of Ukrainian origin, born in Chuhuiv within the Russian Empire, who emerged as a central figure in the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) movement, emphasizing socially conscious art over academic formalism.[1] His works captured the hardships of Russian peasants and laborers, historical dramas, and penetrating portraits of intellectuals and composers, reflecting a commitment to naturalistic representation grounded in direct observation of life.[1] Repin's technical mastery in rendering human emotion and social critique earned him acclaim as one of Russia's foremost artists of the nineteenth century, influencing subsequent generations including early Soviet realism.[1] Repin's breakthrough came with Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870–1873), a monumental canvas depicting exhausted workers towing a barge, symbolizing the exploitation under tsarist rule and establishing his reputation for empathetic genre scenes.[1] Among his most provocative achievements was Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan (1885), portraying the sixteenth-century tsar in a fit of rage fatally striking his heir, which ignited public scandal for humanizing a revered autocrat in a moment of tyrannical violence and led to its temporary censorship before reinstatement amid debates over historical truth versus national myth.[1][2] He produced iconic portraits, such as those of Leo Tolstoy in various introspective poses over decades and Modest Mussorgsky on his deathbed, capturing the psychological depth of Russia's cultural elite.[1] In his later years, Repin relocated to his Penaty estate in Kuokkala, Finland (now Repino, Russia), in 1898, where he continued painting until partial paralysis in 1917; disillusioned with the Bolshevik Revolution, he remained in Finland, effectively in self-imposed exile, and was posthumously honored yet critiqued in Soviet narratives for his pre-revolutionary ties.[1] His oeuvre, blending empirical observation with moral inquiry, remains a cornerstone of Russian art, housed primarily in institutions like the Tretyakov Gallery and State Russian Museum.[1]

Biography

Early Life and Education

Ilya Yefimovich Repin was born on August 5, 1844 (July 24 Old Style), in Chuhuiv, Kharkov Governorate, Russian Empire (now Chuhuiv, Ukraine), into a family of military settlers of Russian ethnicity.[1][3] His father, Yefim Vasilyevich Repin, had served as a soldier for 27 years before engaging in horse trading, while the family operated an inn amid modest circumstances.[1][3] Repin received initial schooling locally and briefly pursued a course in topography and surveying, but his interest gravitated toward art, influenced by his older brother who introduced him to painting materials.[4][3] At age 13, Repin apprenticed under local icon painter Ivan Bunakov, assisting in the creation of religious images for churches and homes.[1][5] By 15, he had established himself as an independent icon painter, joining teams to decorate interiors and amassing savings through commissions to fund further ambitions.[1][6] This practical training honed his technical skills in draftsmanship and color application, though he sought broader artistic development beyond provincial religious art.[1] In autumn 1863, at age 19, Repin relocated to Saint Petersburg with his savings, attempting entry into the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts but failing the entrance examination.[5][7] He then enrolled in a preparatory drawing school led by Ivan Kramskoi, where he refined his abilities and formed connections with aspiring artists.[7][1] In 1864, Repin successfully passed the Academy's entrance and began formal studies, progressing through its rigorous curriculum under professors emphasizing classical techniques and historical themes.[1][5] During this period, he produced works such as Students Studying for an Exam at the Academy of the Arts (1864), reflecting his immersion in academic life.[1]

Academy Training and Initial Recognition

Repin arrived in Saint Petersburg on November 1, 1863, at age nineteen, aspiring to enroll at the Imperial Academy of Arts but failing the initial entrance examination.[8] He audited classes while preparing, demonstrating sufficient progress to gain admission the following year in 1864.[9] His early work Students Studying for an Exam (1864), housed in the State Russian Museum, captures the intensity of academic preparation and reflects his budding realism and attention to detail at age twenty.[10] During his seven-year tenure at the Academy (1864–1871), Repin received progressive recognition through competitive awards. In May 1865, he earned the Small Silver Medal, the institution's lowest accolade, which granted him full student status and privileges.[8] By 1869, he secured the Minor Gold Medal for Job and His Friends, signaling his advancing skill in historical and biblical subjects.[11] Culminating his studies, Repin was awarded the Grand Gold Medal in 1871, enabling a travel pension for artistic development abroad.[3] This honor, tied to his competition piece The Resurrection of Jairus' Daughter, marked his initial prominence within Russian art circles, bridging academic rigor with emerging realist tendencies that would define his career.[8]Rise with the Peredvizhniki Movement

Repin's alignment with the Peredvizhniki, or Association of Traveling Art Exhibitions, emerged from his commitment to realist depictions of Russian social realities, particularly following his 1870 expedition along the Volga River with artist Fyodor Vasilyev. This journey inspired his seminal work Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870–1873), portraying eleven exhausted laborers towing a barge against the current, which captured the movement's emphasis on the hardships of the lower classes and critiqued the dehumanizing effects of manual toil under the tsarist system.[1][12] The painting's raw portrayal of human endurance and subtle hierarchy among the haulers—highlighted by the youthful, defiant figure of the lead hauler—earned widespread acclaim and positioned Repin as a rising voice in realist art.[1] Though not among the group's founders who seceded from the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1863, Repin shared their ideals of accessible, truth-driven art that bypassed academic formalism to reach broader audiences through itinerant shows. He contributed to early Peredvizhniki exhibitions in the 1870s, including displays of Volga studies like Storm on the Volga (1873), which further showcased his evolving mastery of dramatic naturalism intertwined with human struggle.[13][14] These participations, predating his formal membership, marked his initial ascent, as the traveling format amplified exposure and public engagement with his socially charged canvases.[15] Repin officially joined the Association in 1878, solidifying his role amid the group's peak influence in the 1870s and 1880s.[16][17] This affiliation propelled his career, enabling sustained exhibition of works that blended genre scenes with implicit social commentary, such as early studies for religious processions, and fostering collaborations with fellow realists like Ivan Kramskoi and Viktor Vasnetsov.[18] His integration into the Peredvizhniki not only enhanced his reputation but also reinforced the movement's challenge to elite art institutions, drawing critical attention and patronage from reform-minded intellectuals.[19]International Influences and Travels

In 1873, Ilya Repin, funded as a pensioner by the Imperial Academy of Arts, embarked on an extended study trip abroad, first visiting Italy before settling primarily in Paris, France, where he remained until 1876.[20] During this period, he rented a studio in the French capital and immersed himself in the local art scene, producing works such as A Novelty Seller in Paris (1873) and A Paris Cafe (1875), which captured everyday urban life through direct observation.[21] Repin's time in Paris exposed him to the paintings of Eugène Delacroix and the principles of plein-air painting, fostering an appreciation for freer brushwork and natural light that subtly informed his evolving realist style without fully adopting Impressionist tendencies.[22] This encounter with French modernism contrasted with the academic rigor of his Russian training, prompting him to integrate elements of spontaneity into his depictions of Russian subjects upon return.[23] Repin undertook additional travels to Western Europe in the 1880s and beyond, including trips to Austria, Italy, and Germany during the decade, as well as visits in 1883, 1889, 1894, and 1900.[24][6] In 1898, he journeyed to Palestine, an experience that contributed to his exploration of Orientalist themes, drawing on European precedents in exotic subject matter while grounding them in his realist approach.[25] These later excursions reinforced his commitment to observational accuracy but yielded fewer direct stylistic shifts compared to his formative Parisian years.Mature Career and Major Commissions

Repin's mature career from the 1880s onward featured large-scale historical and genre paintings that emphasized dramatic psychological tension and social commentary, often supported by patrons such as Pavel Tretyakov, founder of the Tretyakov Gallery, who acquired many of his works.[17] Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan (1883–1885), measuring 199.5 × 254 cm and housed in the Tretyakov Gallery, portrays the tsar's horror following his fatal blow to his heir on November 16, 1581, blending historical accuracy with intense emotional realism derived from contemporary accounts.[26] This painting, completed after two years of study, exemplifies Repin's shift toward monumental narratives exploring power and regret, influencing later Russian art through its visceral impact.[1] Concurrent with historical subjects, Repin produced Religious Procession in Kursk Province (1880–1883), a sprawling canvas depicting a miracle-working icon's transport amid a cross-section of Russian society, from devout peasants to opportunistic officials, underscoring class disparities and folk traditions observed during his travels.[27] The work's detailed crowd of over 100 figures highlights Repin's technical mastery in composition and lighting, drawing from direct sketches to critique religious fervor intertwined with superstition.[9] Similarly, They Did Not Expect Him (1884–1888), also in the Tretyakov collection, illustrates a Siberian exile's unanticipated return home, capturing familial shock and political undertones of tsarist repression through subtle expressions and domestic clutter.[28] Portrait commissions formed a significant portion of Repin's output, immortalizing Russia's intellectual elite with penetrating psychological insight. In March 1881, he painted Modest Mussorgsky during the composer's final hospital days, rendering the 42-year-old musician's gaunt features and haunted gaze in oil on canvas, now at the Tretyakov Gallery, to convey creative exhaustion amid alcoholism's toll.[29] That same year, Repin completed the portrait of Anton Rubinstein, the pianist-conductor, emphasizing his commanding presence and artistic vigor.[30] His ongoing relationship with Leo Tolstoy yielded multiple portraits, including the 1887 seated study revealing the writer's introspective depth, and 1891 depictions of Tolstoy reading in the forest and writing at Yasnaya Polyana, both acquired by the Tretyakov, which underscore Repin's ability to capture philosophical intensity through naturalistic pose and environment.[31] Repin also tackled epic historical scenes like Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed III (1880–1891), a 203 × 358 cm canvas depicting the Ukrainian Cossacks' defiant letter in 1676, incorporating over 40 figures based on period documents and models to celebrate martial spirit and irreverence.[26] In 1901–1903, he received an official commission for the Ceremonial Sitting of the State Council on 7 May 1901, a vast group portrait of 56 figures including Tsar Nicholas II, executed with photographic precision to document imperial governance, reflecting Repin's versatility in formal state art.[26] By the 1890s, Repin served as professor of painting at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg, mentoring students while continuing independent works that reinforced his status as a pivotal figure in Russian realism.[32]Relocation to Finland and Later Challenges

In 1899, Repin purchased an estate in the village of Kuokkala, part of the Russian Empire's Grand Duchy of Finland, where he designed and built his residence, naming it Penaty after the Roman household deities. He relocated there more permanently around 1903, using it as a summer retreat and studio while wintering in St. Petersburg until the political upheavals of 1917.[11][26] The October Revolution of 1917 and Finland's subsequent declaration of independence on December 6, 1917, transformed Repin's situation dramatically. With the border closure between Finland and Soviet Russia in April 1918, he found himself effectively exiled in Kuokkala, now Repino under Finnish sovereignty, severing direct access to his former networks in St. Petersburg (renamed Petrograd in 1914 and later Leningrad). Repin had initially welcomed the February Revolution's promise of reform but grew deeply disillusioned with the Bolsheviks' ensuing violence and terror, viewing their regime as tyrannical and antithetical to cultural freedoms.[33][9][34] Soviet authorities repeatedly urged Repin to return, with Vladimir Lenin extending an invitation shortly after the revolution, followed by delegations under Joseph Stalin in the 1920s, including his former student Isaak Brodsky, offering honors and resources to lure the aging artist back as a symbol of continuity. Repin consistently declined, citing frailty, the physical impossibility of travel, and his contempt for Bolshevik authoritarianism, which he equated in oppressiveness to the tsarist autocracy he had once critiqued. This stance isolated him further, as Finland's neutrality shielded him from persecution but also from Soviet artistic patronage and exhibitions.[35][17][5] Compounding these political estrangements were physical ailments: by the early 1900s, Repin suffered partial paralysis in his right hand, likely from overwork and neuritis, which progressively limited his ability to paint with precision and forced adaptations like using his left hand or relying on assistants for finishing works. Despite these constraints, he produced sketches, portraits of local Finns, and experimental pieces at Penaty, though his output dwindled amid the solitude and lack of Russian models or stimuli. Repin died at the estate on September 29, 1930, at age 86, his later years marked by a defiant independence that preserved his realist ethos amid revolutionary chaos.[36][37][1]Personal Life

Family, Marriages, and Domestic Affairs

Repin married Vera Alekseevna Shevtsova, the daughter of his landlord Alexei Ivanovich Shevtsov, in 1872.[38][1] The couple had four children: daughter Vera, born in 1872; daughter Nadezhda, born in 1874; son Yuri, born in 1877; and daughter Tatiana, born in 1880.[38][39] Domestic life was strained, as Repin pursued extramarital affairs while Shevtsova managed childcare and household duties amid his demanding artistic career; the marriage ended in separation around 1884 and formal divorce by 1887.[1][39] In 1900, Repin entered a second marriage with writer Natalia Borisovna Nordman-Severova (1863–1914), whom he had met a decade earlier.[40][41] The union had no children but influenced Repin's lifestyle; Nordman, a vegetarian and women's rights advocate, prompted him to adopt a plant-based diet and relocate to her estate, Penaty (The Penates), in Kuokkala, Finland (now Repino, Russia), where they resided until her death from tuberculosis in 1914.[40][24] Repin's son Yuri, an aspiring artist, lived intermittently at Penaty but struggled with mental health issues, leading to his isolation there as a recluse in later years.[42]Key Intellectual and Artistic Associations

Repin formed enduring artistic ties with the Peredvizhniki, or Wanderers, joining their Association of Traveling Art Exhibitions in 1878 after initial associations during his Academy years; key collaborators included Ivan Kramskoi, the group's ideological leader who mentored Repin in realist principles, and Vasily Polenov, a fellow student and lifelong friend from St. Petersburg Academy days.[1][15] These connections emphasized socially conscious realism, with Repin contributing to their itinerant exhibitions that critiqued tsarist autocracy and rural hardships through paintings like Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870–1873).[16] Intellectually, Repin's friendship with Leo Tolstoy commenced in 1880 when Tolstoy visited his Moscow studio, evolving into mutual influence marked by visits to Yasnaya Polyana and debates on art's moral role; Repin produced at least eleven portraits of Tolstoy from 1881 to 1910, capturing the writer's asceticism and physical decline, though their bond strained over Tolstoy's rejection of professional artistry as elitist.[43] The critic Vladimir Stasov, a fervent advocate of nationalist art, bolstered Repin's career by promoting his works and introducing radical publications like those of the Narodnaya Volya group, fostering Repin's engagement with populist and anti-autocratic ideas.[44] Repin also cultivated associations with Russia's nationalist composers, often linked through Stasov and shared cultural circles; he painted Modest Mussorgsky in March 1881 during the composer's final days from alcoholism, rendering a stark, unflattering likeness that highlighted personal decline, while portraying Alexander Borodin in 1888 and Anton Rubinstein in 1881 amid their mutual interest in Slavic themes.[3] These portraits reflected Repin's immersion in the "Mighty Handful" milieu, where music and visual art converged in evoking Russian folk essence, though relationships varied from professional commissions to casual acquaintances rather than deep collaborations.[45]Artistic Production

Genre and Social Realist Paintings

Repin's genre paintings frequently depicted scenes of Russian peasant and working-class life, infused with social realist elements that critiqued exploitation and inequality, aligning with the Peredvizhniki group's emphasis on truthful portrayals of societal conditions over idealized academic subjects.[46] These works drew from direct observations, emphasizing empirical realism in composition and human expression to convey causal links between labor conditions and human suffering.[47] His seminal social realist painting, Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870–1873), portrays eleven exhausted burlaks—seasonal laborers—straining to tow a barge upstream along the Volga River under harsh summer conditions. Conceived during Repin's 1870 travels by steamer on the river, where he sketched real individuals including peasants, convicts, and a former monk, the canvas highlights physical degradation through detailed anatomy, tattered clothing, and bowed postures, while the defiant gaze of the young central hauler suggests emerging resistance against systemic toil.[47] [48] Exhibited in 1873 with the Peredvizhniki, it garnered praise for exposing the dehumanizing effects of manual labor in imperial Russia, influencing public discourse on reform.[49]

In Religious Procession in Kursk Province (1880–1883), Repin rendered an Easter procession bearing the icon of the Virgin of the Sign, blending devout pilgrims with corrupt officials, drunken merchants, and superstitious peasants to underscore hypocrisies in church-state relations and popular religiosity. Based on studies from actual Kursk processions observed in the late 1870s, the composition's crowded diagonal thrust and individualized faces—ranging from ecstatic to opportunistic—reveal social stratification and moral decay without overt didacticism.[46] Acquired by Pavel Tretyakov for 10,000 rubles upon its 1883 exhibition, the work provoked debate on institutional abuses, as Repin intended to depict "the entire Russian people" in their varied authenticity.[50] They Did Not Expect Him (1884–1888) captures the tense reunion of a pardoned political prisoner with his bourgeois family in a dimly lit interior, their expressions mixing shock, fear, and tentative hope to illustrate the pervasive chill of autocratic surveillance on private life. Prompted by amnesties following Alexander III's 1880 ascension amid revolutionary unrest, including the 1881 regicide, Repin drew from contemporary accounts of exiles' returns, using subtle lighting and frozen postures to evoke psychological realism and the human cost of dissent.[44] [51] Displayed at the 1888 Peredvizhniki exhibition, it addressed suppressed narratives of political incarceration, resonating in an era of heightened censorship.[52] These paintings collectively advanced social realism by grounding critique in observed particulars, prioritizing causal depictions of environment's toll on individuals over abstract moralizing.[53]

Historical and Nationalistic Works

Repin's historical paintings frequently depicted pivotal moments from Russian history, emphasizing dramatic psychological tension and the human cost of power. These works, executed with meticulous realism, drew from primary historical sources and aimed to evoke empathy for complex figures amid autocratic rule. Among his most renowned is Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan (1885), portraying Tsar Ivan IV cradling his mortally wounded son, Ivan Ivanovich, following a fatal blow struck on November 16, 1581, during a heated argument reportedly triggered by the son's pregnant wife appearing underdressed before the tsar.[54] [55] The canvas captures the tsar's immediate regret and horror, with blood pooling from the son's head wound, underscoring themes of tyrannical rage and irreversible consequence; exhibited at the 20th Peredvizhniki show, it provoked controversy, leading to a temporary ban by imperial censors in 1885 over fears of inciting regicidal sentiments, though it was reinstated after public outcry.[2] Another significant historical piece, The Tsarevna Sophia Alekseyevna (1879), illustrates the regent's confinement in the Novodevichy Convent after her 1689 overthrow by her half-brother Peter the Great. Repin depicts Sophia in monastic garb, seated amid sparse furnishings, her posture conveying a mix of resignation and latent defiance reflective of her role as a politically ambitious figure who had briefly wielded power during the minority of Tsars Ivan V and Peter I from 1682 to 1689.[56] The painting, housed in the Tretyakov Gallery, highlights the personal toll of dynastic intrigue, with Repin's attention to costume and expression drawing from convent records and portraits to evoke the tragedy of fallen royalty.[57] Repin's nationalistic inclinations surfaced prominently in Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks (1880–1891), a large-scale canvas commemorating the 17th-century Cossacks' defiant response to Sultan Mehmed IV's 1676 demand for submission. The work shows the Zaporozhian Sich leaders, including hetman Ivan Sirko, composing a scathingly humorous letter filled with insults—such as calling the sultan a "Turkish devil and strumpet"—symbolizing Slavic resistance to Ottoman imperialism and autocratic overreach.[58] [59] Repin incorporated models from Ukrainian and Russian circles, infusing the scene with boisterous camaraderie to celebrate Cossack autonomy and democratic ethos, traits viewed as emblematic of proto-nationalist fervor; completed after over a decade of study, including trips to Ukraine, it resides in the State Russian Museum and embodies Repin's vision of historical vitality as a bulwark against despotism.[60] These paintings collectively reflect Repin's engagement with Russia's past not as mere chronicle but as a lens for examining enduring tensions between authority and individual agency, often laced with subtle critique of contemporary tsarist parallels.[61]Portraits and Figure Studies

Repin's portraits emphasized psychological depth, capturing the subject's character through expressive poses, lighting, and facial details rooted in direct observation.[1] He produced portraits of prominent Russian intellectuals, composers, and writers, often during brief sittings that demanded rapid execution to seize fleeting expressions.[1] These works avoided flattery, prioritizing truthful representation over idealization, as seen in his depiction of subjects in moments of contemplation or fatigue. A prime example is the Portrait of Modest Mussorgsky (1881, oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), painted in the final days before the composer's death from alcoholism; Repin conveyed Mussorgsky's exhaustion and genius through disheveled features and intense gaze, completed in three sessions.[62] Similarly, the Portrait of Anton Rubinstein (1881, Tretyakov Gallery) portrays the pianist in dynamic profile, highlighting his energetic persona amid a musical score. Repin executed multiple portraits of Leo Tolstoy, including one in 1887 (oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery) showing the writer seated with a book, emphasizing his contemplative austerity.[63] His figure studies, frequently preparatory for genre or historical compositions, focused on anatomical precision and naturalistic movement, drawn from live models to ensure verisimilitude.[1] These included nude and draped figures, as well as ethnic types observed during travels, serving to build authentic compositions like those in Barge Haulers on the Volga.[1] Repin transformed such studies into psychologically charged elements, basing characters on amalgamated real individuals to heighten dramatic realism without caricature.[51] Later portraits, such as Alexander Borodin (1888) and posthumous Mikhail Glinka (1887), extended this approach to composers, integrating personal artifacts to evoke creative essence. Repin's method involved exhaustive sketching to dissect form and emotion, contributing to his reputation for penetrating human insight in Russian art.[1]Drawings, Sketches, and Etchings

Repin produced over five hundred drawings, sketches, and related graphic works across his career, many serving as preparatory studies that captured anatomical details, expressions, and compositions for his major paintings. These pieces highlight his rigorous preparatory process, emphasizing empirical observation and iterative refinement through direct sketching from life. Techniques included pencil for precise line work and shading, charcoal for bold tonal contrasts, quill pen for fluid ink lines, and graphite for subtle modeling, particularly in portrait studies of intellectuals and artists.[64][65] During his Paris residence from 1873 to 1876, Repin compiled a sketchbook containing 129 drawings, predominantly in pencil with seven in colored crayon and two in ink, documenting urban scenes, individual figures, clothing, and group dynamics. This volume, which includes notes on sitters' physical traits and a 1873 self-portrait on its cover, informed key works like A Parisian Café (1875) and A Novelty Seller in Paris (1873), revealing his methodical approach to integrating observed details into finished oils. Acquired by the Musée d'Orsay in 2022 through the Meyer Louis-Dreyfus Fund, the sketchbook underscores Repin's academic training in line mastery and his adaptation of French influences to Russian realist aims.[20] For Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870–1873), Repin conducted multiple site visits to the Volga River, yielding extensive sketches of laborers' physiques, gaits, and the riverine environment to ensure naturalistic accuracy in the final canvas. An early compositional sketch from 1870 outlines the procession's arrangement, while figure studies emphasized muscular strain and varied postures among the haulers. Similarly, preparatory drawings for Storm on the Volga (1873) focused on turbulent water and atmospheric effects, prioritizing dynamic form over idealized rendering. These sketches often exhibited greater immediacy and psychological intensity than the polished paintings, as noted by art analysts reviewing museum holdings.[1] Repin also created standalone drawings, such as a 1890 pencil portrait of a Cossack on paper laid to cardboard, demonstrating his skill in capturing ethnic attire and resolute expressions. His etching output was more limited, with examples like A Woman in a Cap employing intaglio to render fabric textures and facial contours through etched lines and aquatint tones, though prints formed a minor aspect of his oeuvre compared to drawings.[66][67]Style and Technique

Core Principles of Realism

Repin's adherence to realism, shaped by his association with the Peredvizhniki movement founded in 1870, centered on faithful representation of everyday Russian life through direct observation and meticulous study.[14] He rejected the Imperial Academy's neoclassical emphasis on idealized historical subjects, instead prioritizing naturalistic depictions of ordinary people, laborers, and social conditions to convey unvarnished truth.[1] This approach demanded extensive on-site sketching and research, as seen in his preparation of numerous studies for works like Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870–1873), where he individualized each figure based on real models to achieve hyper-naturalistic detail.[14] Central to his philosophy was the principle that art must be "clear and faithful to the truth," capturing the poetic essence of reality without romantic embellishment.[1] Repin integrated empathy and psychological depth, using harmonious application of color, line, and tonal gradations to express mood and individual character, thereby highlighting human struggles and societal inequities.[1] In Barge Haulers on the Volga, for instance, the near-photographic accuracy of forms and light underscores the physical toll of labor, embodying the Peredvizhniki's commitment to social critique through empathetic realism rather than overt propaganda.[13] His technique emphasized precision in rendering light, texture, and expression to evoke emotional resonance, distinguishing his works from mere documentation by infusing observed reality with insightful pathos.[1] Repin viewed Russian reality as inherently compelling, capable of drawing viewers into its authentic narratives, which aligned with the movement's goal of making art accessible and relevant to the broader populace via traveling exhibitions that reached over 40,000 annual visitors by 1877.[1][13] This democratic ethos reinforced realism's core tenet of accuracy over artifice, ensuring depictions served humanitarian ideals by exposing truths of peasant life and autocratic oppression.[14]

.jpg/250px-RepinSelfPortrait_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)