Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Mira.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

from Grokipedia

Mira (ο Ceti), also known as the "Wonderful Star," is a red giant star located in the constellation Cetus, serving as the prototype for a class of pulsating variable stars known as Mira variables.[1][2] This asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star, with a spectral type of M7IIIe and a mass of approximately 1.2 solar masses, undergoes regular pulsations that cause its visual brightness to vary dramatically over a period of about 332 days, ranging from a maximum of around 2nd magnitude (visible to the naked eye) to a minimum of 10th magnitude (requiring a telescope).[3][2]

Discovered as a variable star in August 1596 by Dutch astronomer David Fabricius, who initially mistook it for a nova due to its sudden appearance and subsequent fading, Mira was the first long-period variable identified beyond novae and eclipsing binaries like Algol.[4][5] In 1638, Phocylides Holwarda conducted systematic observations that revealed its roughly 330-day cycle, confirming its periodic nature and earning it the Latin name Mira ("wonderful") in 1662 by Hevelius for its remarkable variability.[6] At a distance of approximately 300 light-years (92 parsecs) from Earth, Mira is the nearest example of a wind-accreting binary system, consisting of the red giant primary orbited by a white dwarf companion (Mira B, or VZ Ceti) at a separation of about 100 AU over an orbital period of roughly 500 years.[7][3]

As an evolved star nearing the end of its life, Mira exhibits a diameter of about 650 million kilometers—roughly 470 times that of the Sun—and a surface temperature around 3,000 K, contributing to its reddish hue and strong emission lines from surrounding dust and gas.[3] It is actively losing mass through stellar winds, forming a comet-like tail extending over 13 light-years, as observed by NASA's Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) in 2007, while the star travels through space at a high proper motion of about 130 km/s relative to the Local Standard of Rest.[8] These properties make Mira a key object for studying late-stage stellar evolution, mass loss in AGB stars, and the dynamics of symbiotic binary systems, with potential implications for its eventual transformation into a planetary nebula.[7][9]

Identification

Nomenclature

The name Mira originates from the Latin term mira, meaning "wonderful" or "astonishing," which was assigned by the Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius in his 1662 work Historiola Mirae Stellae to highlight the star's striking variability.[3] This moniker reflects the astonishment it elicited among early observers due to its periodic brightening and fading.[10] In 2016, the International Astronomical Union approved the name Mira for this star.[11] Prior to this, the star received its Bayer designation as Omicron Ceti (ο Ceti) from Johann Bayer in his 1603 star atlas Uranometria, where it was cataloged as a fourth-magnitude star in the constellation Cetus.[12] It also appears in other major catalogs, including the Henry Draper Catalogue as HD 14386, Flamsteed's numbering as 68 Ceti, and the AAVSO variable star index as 0214-03.[13] Common alternative designations include Mira Ceti and o Ceti, the latter a simplified form of the Bayer name.[14] In modern Chinese astronomical nomenclature, it is referred to as 米拉 (Mǐlā), a transliteration of the Latin name.[15]Location and Visibility

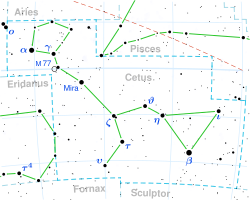

Mira, also known as Omicron Ceti, resides in the constellation Cetus. Its position in the sky is given by J2000.0 coordinates of right ascension 02ʰ 19ᵐ 20.⁸ and declination −02° 58′ 39″.[16] These coordinates place Mira near the celestial equator, facilitating observation from both hemispheres under suitable conditions. As a long-period variable star, Mira exhibits an apparent visual magnitude that fluctuates between 2.0 at maximum brightness and 10.1 at minimum, rendering it naked-eye visible during peak phases from dark-sky sites. At its brightest, it rivals second-magnitude stars, though it requires binoculars or a small telescope when fainter than magnitude 6. From the Northern Hemisphere, Mira is optimally visible during the autumn and winter seasons, rising in the southeast after sunset and reaching a high southern altitude by midnight.[4] Observers in mid-northern latitudes can track it from late August through April, though it becomes unobservable near the Sun from late March to June. In the Southern Hemisphere, its near-equatorial declination allows visibility for much of the year, peaking overhead during local spring and summer evenings. Mira displays a proper motion of +9.33 mas/yr in right ascension and −237.36 mas/yr in declination, indicating a predominantly southward drift across the sky. This transverse motion translates to a tangential velocity of approximately 103 km/s relative to the Sun, combining with its heliocentric radial velocity of +63.8 km/s to yield a total space velocity of about 130 km/s relative to the local standard of rest. The direction of this high-speed travel through the interstellar medium is aligned with the star's observed bow shock and trailing wake.Observation History

Pre-Telescopic Records

The variability of Mira, a long-period variable star with a pulsation cycle of approximately 331 days, allows it to reach naked-eye visibility at maximum brightness of around 2.0 magnitude during rare bright peaks, though its red color (B-V ≈ 1.3–1.4) reduces the effective naked-eye limit to about 4.5–6.0 magnitude under typical conditions. This has fueled scholarly debate on whether ancient observers could have detected it without telescopes, particularly given cultural biases against recognizing stellar changes in fixed ancient skies and the infrequency of sufficiently bright apparitions. Possible pre-telescopic records include a suggested observation by the Greek astronomer Hipparchus around 134 BC, when Mira may have been at a bright maximum, as inferred from historical analyses of his catalog, though direct confirmation is lacking. In the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder described a "new star" in the region of Cetus, but this is widely regarded as a comet rather than Mira, with no mention of variability. Chinese astronomical annals record a guest star in the Tianjun asterism on December 25, 1070 AD, positioned near Mira's location, potentially aligning with a historical peak; however, it was interpreted as a comet, and no variability was noted, leaving the identification inconclusive. Despite these potential alignments—such as estimated bright peaks around 137 BC and 1077 AD based on the star's period—there is no definitive pre-17th-century evidence of Mira's variability, and the scholarly debate remains unresolved, with most experts attributing the absence of records to observational limitations and the star's inconsistent brightness rather than complete oversight.Post-Telescopic Discovery

The first confirmed observation of Mira's variability occurred on August 3, 1596, when Dutch astronomer David Fabricius (1564–1617) noted a previously unrecorded star of about third magnitude in the constellation Cetus while searching for Mercury; he initially classified it as a nova, but by October it had faded from visibility.[10] Fabricius reobserved the star on February 15, 1609, confirming its return near the same position, marking the earliest documented record of a variable star's periodicity, though he did not recognize the recurrent nature at the time.[17] These naked-eye detections predated widespread telescope use but established Mira as o Ceti in early star catalogs. In 1638, Dutch astronomer Phocylides Holwarda conducted the first systematic observations of Mira over an extended period, determining its variability cycle to be approximately 330 days and thereby first recognizing its periodic nature.[18] In 1662, Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius (1611–1687) systematically tracked Mira over multiple cycles, recognizing its regular waxing and waning brightness as unlike any fixed star, and named it Stella Mira ("Wonderful Star") in his work Historiola Mirae Stellulae in Cete, emphasizing its extraordinary behavior.[19] Hevelius's observations, spanning from 1659 to 1661, documented the star's disappearance and reappearance, solidifying its status as the prototype of long-period variables.[17] During the 19th century, German astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm August Argelander (1799–1875) and collaborators conducted extensive photometric monitoring of Mira, compiling over 1,000 observations that refined its variability cycle to approximately 330 days, providing a foundational dataset for variable star astronomy.[17] Argelander's systematic approach, detailed in publications like Bonner Durchmusterung (1859–1862), highlighted Mira's consistent period despite amplitude fluctuations, influencing the establishment of variable star observing networks.[20] Early 20th-century spectroscopic studies, beginning with Alfred H. Joy's work at Mount Wilson Observatory in the 1920s, revealed Mira's radial velocity variations of up to 50 km/s synchronized with its light cycle, indicating atmospheric pulsations as the cause of variability.[21] These observations, using absorption lines in the star's M-type spectrum, confirmed the pulsation's role in driving mass loss and brightness changes, advancing understanding of red giant evolution.[22]Physical Properties

Distance and Motion

Mira's distance from the Solar System has been determined primarily through trigonometric parallax measurements from space-based astrometry. The distance is approximately 123 parsecs (400 light-years), based on Hipparcos parallax of about 8.1 mas and refined estimates from other methods.[24] The Gaia mission's Data Release 3 (2022) provides astrometric data, but for bright, variable stars like Mira, measurements have larger uncertainties due to saturation and pulsation effects, and are not used as the primary distance indicator.[25] Historical estimates from the Hipparcos mission in the 1990s placed Mira at 120–150 parsecs, based on parallaxes of roughly 6.7–8.3 milliarcseconds; these values align well with modern estimates from combined measurements. Mira's space motion includes a radial velocity of approximately +64 km/s, indicating recession from the Sun, and a tangential velocity of ~110–140 km/s derived from its proper motion and distance. The resulting total velocity of ~130 km/s relative to the Local Standard of Rest situates Mira within the local galactic stellar population, tracing an orbit typical of thin-disk stars.[7] The proper motion components contribute to long-term visibility changes in the sky but are secondary to the parallax for distance determination.[25]Stellar Parameters

Mira is classified as a late-type red giant with a spectral type of M7IIIe, characterized by strong molecular bands of titanium oxide (TiO) in its spectrum and emission lines indicative of a pulsating atmosphere. The effective temperature of its photosphere ranges from approximately 2900 K to 3000 K, reflecting the cool outer layers typical of such evolved giants. This temperature regime contributes to the star's distinctive red color and its placement on the cool end of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram among asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars. Mira has an estimated mass of about 1.2 solar masses (M⊙), consistent with its AGB evolutionary phase. The stellar radius of Mira varies with its pulsation cycle but averages between 400 and 600 solar radii (R⊙), making it one of the largest known stars. Its bolometric luminosity, which accounts for emission across all wavelengths, is estimated at 4000 to 8000 solar luminosities (L⊙), driven by the energy release from internal nuclear processes. These dimensions and brightness levels underscore Mira's status as a luminous, extended object, with the radius derived from interferometric measurements of its angular diameter combined with parallax data.[3] Surface gravity on Mira's photosphere is low, with log g ≈ -0.5, consistent with the weak gravitational pull on its expansive envelope. The star exhibits a composition typical of slightly metal-poor giants. As an AGB star, Mira is in a late evolutionary phase where hydrogen fusion has ceased in the core, and energy is primarily generated through helium-shell burning surrounding a degenerate helium core. This stage involves thermal pulses that periodically ignite helium fusion, leading to the expansion and pulsations observed in Mira variables.Variability

Pulsation Cycle

Mira serves as the prototype for Mira variables, a subclass of long-period variables consisting of asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars that exhibit large-amplitude pulsations.[26] The primary pulsation period of Mira is approximately 332 days, as determined from extensive photometric observations.[24] These pulsations arise from radial oscillations in the star's extended envelope, where convective instability drives periodic expansions and contractions with a velocity amplitude of 20–30 km/s, as measured from high-excitation spectral lines.[27] The resulting light variation is roughly sinusoidal but asymmetric, featuring a steep rise to maximum brightness over roughly one-third of the cycle followed by a more gradual decline; visual magnitudes typically peak at 3.4 and fade to a minimum of 9.3, though cycle-to-cycle variations can result in extremes of about 2.0 to 10.1 mag.[24][1][3]Amplitude and Spectrum

Mira's variability is characterized by a typical visual amplitude of approximately 6 magnitudes.[24] This large change in apparent magnitude is a defining feature of Mira-type variables, driven by the pulsation cycle with a period of approximately 332 days.[24] In the infrared, the amplitude is smaller than in the visual band, typically around 3 magnitudes in the K-band, due to the reduced sensitivity of longer wavelengths to the temperature variations during the cycle.[28] The spectral type of Mira evolves significantly over its variability cycle, shifting from M5e at maximum light to M9e at minimum light.[29] This change reflects cooling of the stellar atmosphere, with titanium oxide (TiO) bands becoming stronger and more prominent near minimum, contributing to the star's redder appearance during its fainter phases.[30] The strengthening TiO absorption is a key spectroscopic indicator of the atmospheric dynamics in Mira variables. Corresponding to these spectral shifts, Mira's color index (B-V) varies from about +1.0 at maximum to +2.5 at minimum, underscoring the substantial drop in effective temperature as the star fades.[31] This reddening effect amplifies the visual amplitude, as the emission shifts toward longer wavelengths where the eye is less sensitive. Analysis of observed-minus-calculated (O-C) diagrams reveals a possible long-term trend in Mira's pulsation period. This secular evolution may be linked to structural changes in the star's envelope, though the effect is subtle and requires long-baseline observations for confirmation.[32]Binary System

Orbital Parameters

The Mira binary system has an orbital period of roughly 500 years. Recent astrometric data, including from Gaia, support parameters consistent with historical estimates, though refinements continue due to the long period. The relative orbit has an angular semi-major axis of approximately 0.5 arcseconds, equivalent to a physical semi-major axis of about 100 AU at the system's distance of approximately 123 parsecs (400 light-years).[33] This orbit is highly eccentric, with an eccentricity of ~0.98, resulting in extreme variations in separation between the components over the orbital cycle.[34] The orbital inclination relative to the plane of the sky is approximately 100–130°, which implies a periastron distance of roughly 0.8 AU. Such close approaches at periastron enable periodic accretion events as the companion passes through the denser inner regions of the primary's wind. Determination of these orbital elements relies on high-resolution techniques, including speckle interferometry for resolving the pair's relative position and Gaia astrometric measurements for precise proper motions and parallax. These modern methods have significantly refined historical visual orbit calculations, which suffered from larger uncertainties due to the system's long period and faint companion, providing better constraints on the eccentricity and inclination through integration of multi-epoch data spanning centuries.[35]Mira A

Mira A is the primary component of the Mira binary system, classified as an asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star with a current mass of approximately 1.0–1.2 M⊙.[36] This mass reflects significant envelope loss during its post-main-sequence evolution from an initial progenitor of roughly twice the solar mass. As an AGB star, Mira A undergoes periodic thermal pulses in its helium-burning shell, occurring approximately every 10,000 years, which drive convective mixing and third dredge-up episodes that enrich its surface composition.[37] These pulses contribute to the star's high luminosity and instability, marking it as the prototypical Mira variable. The physical size of Mira A is substantial, with interferometric measurements revealing an angular diameter of about 30 mas in the near-infrared during its pulsation cycle.[38] Near maximum light, the limb-darkened angular diameter reaches approximately 43 mas at 2.2 μm, corresponding to a physical radius of roughly 575 R⊙ assuming a distance of 123 pc.[39][40] This large radius underscores its extended envelope, where the photosphere expands and contracts significantly over its ~332-day pulsation period. The intense surface convection in Mira A, coupled with its radial pulsations, is influenced by the binary nature of the system, where tidal forces from the companion potentially amplify these dynamical processes. Orbital effects at periastron may further perturb the star's outer layers, enhancing atmospheric dynamics during close approaches.[41]Mira B

Mira B is the compact secondary component in the Mira binary system, identified as a white dwarf with an estimated mass of approximately 0.6 M_\sun and an effective temperature around 14,000 K.[42][43] This white dwarf accretes material from the wind of its primary companion, powering its emission across multiple wavelengths.[42] The white dwarf nature of Mira B was inferred from ultraviolet observations beginning in the late 1970s, which detected an ultraviolet excess inconsistent with the cool primary star alone.[44] Confirmation came from spectra obtained with the International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE) between 1979 and 1985, revealing a hot continuum source dominating the UV flux during the primary's light minimum; analysis showed broad emission lines and a variable UV spectrum attributable exclusively to Mira B.[44][42] X-ray observations by the Chandra X-ray Observatory provide direct evidence for an accretion disk surrounding Mira B, where infalling material from the primary's stellar wind collides and heats up, producing soft X-ray emission with temperatures around 4 million K.[45] These detections, resolved spatially from the primary, highlight the disk's role in the system's energy output and variability.[46] Evolutionary models indicate that Mira B originated as a main-sequence star of roughly solar mass, which evolved to fill its Roche lobe and underwent a common envelope phase with the progenitor of the primary, ejecting the envelope and leaving the white dwarf in a close orbit.[42] This post-common envelope configuration facilitates ongoing wind accretion, shaping the current dynamics of the binary. The orbital proximity enables significant interactions, including mass transfer that sustains the accretion processes observed.[42]Circumstellar Environment

Mass Loss

Mira A's mass loss is primarily driven by radiation pressure on dust grains condensed in its extended atmosphere, resulting in a steady stellar wind that characterizes its late asymptotic giant branch evolution. Observations of CO rotational lines indicate a current mass-loss rate of approximately M yr, with some recent high-resolution studies suggesting values as low as M yr for the combined bipolar outflows when accounting for anisotropy.[47][48] The outflow reaches terminal velocities of roughly 3-5 km s, as determined from the velocity gradients and line profiles in CO emission, which trace the acceleration of the wind from the stellar surface outward. These measurements reveal a slow expansion consistent with dust-driven dynamics, where the gas is coupled to dust grains accelerated by stellar photons.[49] Pulsations in Mira A's atmosphere enhance mass loss by generating shock waves that propagate outward, particularly during the post-maximum phase of the cycle, lifting dense material to cooler regions where dust formation is favored and enabling more efficient momentum transfer. This pulsation-enhanced dust-driven process leads to episodic variations in the outflow rate, superimposed on the average steady loss.[50] Over the entire asymptotic giant branch phase, Mira A is estimated to have lost a total of 0.2-0.4 M from its envelope, based on evolutionary models matching its pulsation properties and current parameters. The binary companion, Mira B, may briefly modulate this loss through gravitational interactions that shape the wind geometry.[51][48]Molecular Envelope

The molecular envelope surrounding Mira consists primarily of cool gas and dust ejected from the primary star, Mira A, with key molecular species including silicon monoxide (SiO), water vapor (H₂O), and carbon monoxide (CO). These molecules trace different layers of the envelope: SiO emission is prominent in the innermost regions near the stellar surface, H₂O appears in intermediate zones beyond the dust condensation region, and CO dominates the outer, more extended parts where it serves as a reliable tracer of the overall mass distribution.[52][53] High-resolution Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) observations reveal that the extended envelope spans radii of approximately 100–200 AU, encompassing structured features such as detached arcs and outflows observable in ¹²CO(3–2) emission up to about 250 AU from the binary center.[54] The envelope exhibits pronounced asymmetries, driven by gravitational torque from the companion Mira B, which perturbs the outflowing material and imprints spiral or bipolar patterns, including a south-western outflow and north-eastern arms with velocities of 5–10 km s⁻¹.[54] Dust grains, particularly alumina (Al₂O₃), form close to Mira A at radii of roughly 2–3 stellar radii (about 5–10 AU), where they condense in the dynamically active atmosphere and enhance opacity, thereby accelerating the wind and modulating the star's photometric variability through scattering and absorption.[27] ALMA imaging further discloses intricate dynamics within this region, including shock-induced fragmentation in CO and SiO distributions and a large-scale bow shock interacting with the interstellar medium at greater distances, though inner envelope structures at ~100 AU show evidence of turbulent shocks from episodic ejections.[54]References

- https://science.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/missions/hubble/hubble-separates-stars-in-the-mira-binary-system/