Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Uniform Resource Name

View on WikipediaA Uniform Resource Name (URN) is a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) that uses the urn scheme. URNs are globally unique persistent identifiers assigned within defined namespaces so they will be available for a long period of time, even after the resource which they identify ceases to exist or becomes unavailable.[1] URNs cannot be used to directly locate an item and need not be resolvable, as they are simply templates that another parser may use to find an item.

URIs, URNs, and URLs

[edit]URNs were originally conceived to be part of a three-part information architecture for the Internet, along with Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) and Uniform Resource Characteristics (URCs), a metadata framework. As described in RFC 1737,[2] and later in RFC 2141,[3] URNs were distinguished from URLs, which identify resources by specifying their locations in the context of a particular access protocol, such as HTTP or FTP. In contrast, URNs were conceived as persistent, location-independent identifiers assigned within defined namespaces, typically by an authority responsible for the namespace, so that they are globally unique and persistent over long periods of time, even after the resource which they identify ceases to exist or becomes unavailable.[1]

URCs never progressed past the conceptual stage,[4] and other technologies such as the Resource Description Framework later took their place. Since RFC 3986[5] in 2005, use of the terms "Uniform Resource Name" and "Uniform Resource Locator" has been deprecated in technical standards in favor of the term Uniform Resource Identifier (URI), which encompasses both, a view proposed in 2001 by a joint working group between the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF).[4]

A URI is a string of characters used to identify or name a resource on the internet. URIs are used in many Internet protocols to refer to and access information resources. URI schemes include the http and ftp protocols, as well as hundreds of others.

In the "contemporary view", as it is called, all URIs identify or name resources, perhaps uniquely and persistently, with some of them also being "locators" which are resolvable in conjunction with a specified protocol to a representation of the resources.

Other URIs are not locators and are not necessarily resolvable within the bounds of the systems where they are found. These URIs may serve as names or identifiers of resources. Since resources can move, opaque identifiers which are not locators and are not bound to particular locations are arguably more likely than identifiers which are locators to remain unique and persistent over time. But whether a URI is resolvable depends on many operational and practical details, irrespective of whether it is called a "name" or a "locator". In the contemporary view, there is no bright line between "names" and "locators".

In accord with this way of thinking, the distinction between Uniform Resource Names and Uniform Resource Locators is now no longer used in formal Internet Engineering Task Force technical standards, though the latter term, URL, is still in wide informal use.

The term "URN" continues now as one of more than a hundred URI "schemes", urn:, paralleling http:, ftp:, and so forth. URIs of the urn: scheme are not locators, are not required to be associated with a particular protocol or access method, and need not be resolvable. They should be assigned by a procedure which provides some assurance that they will remain unique and identify the same resource persistently over a prolonged period. Some namespaces under the urn: scheme, such as urn:uuid: assign identifiers in a manner which does not require a registration authority, but most of them do. A typical URN namespace is urn:isbn, for International Standard Book Numbers. This view is continued in RFC 8141 (2017).[1]

There are other URI schemes, such as tag:, info: (now largely deprecated), and ni:[6] which are similar to the urn: scheme in not being locators and not being associated with particular resolution or access protocols.

Syntax

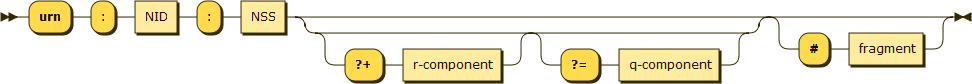

[edit]The syntax of a urn: scheme URI is represented in the augmented Backus–Naur form as:[5][7]

namestring = assigned-name

[ rq-components ]

[ "#" f-component ]

NID = (alphanum) 0*30(ldh) (alphanum)

ldh = alphanum / "-"

NSS = pchar *(pchar / "/")

rq-components = [ "?+" r-component ]

[ "?=" q-component ]

r-component = pchar *( pchar / "/" / "?" )

q-component = pchar *( pchar / "/" / "?" )

f-component = fragment

; general URI syntax rules (RFC3986)

fragment = *( pchar / "/" / "?" )

pchar = unreserved / pct-encoded / sub-delims / ":" / "@"

pct-encoded = "%" HEXDIG HEXDIG

unreserved = ALPHA / DIGIT / "-" / "." / "_" / "~"

sub-delims = "!" / "$" / "&" / "'" / "(" / ")" / "*" / "+" / "," / ";" / "="

alphanum = ALPHA / DIGIT ; obsolete, usage is deprecated

or, in the form of a syntax diagram, as:

- The leading scheme (

urn:) is case-insensitive. <NID>is the namespace identifier, and may include letters, digits, and-.- The NID is followed by the namespace-specific string

<NSS>, the interpretation of which depends on the specified namespace. The NSS may contain ASCII letters and digits, and many punctuation and special characters. Disallowed ASCII and Unicode characters may be included if percent-encoded.

In 2017, the syntax for URNs was updated:[1]

- The slash character (

/) is now allowed in the NSS to represent names containing slashes from non-URN identifier systems. - The q-component was added to enable passing of parameters to named resources.

- The r-component was added to enable passing of parameters to resolvers. However, the updated specification notes that it should not be used until its semantics are defined via further standardization.

Namespaces

[edit]In order to ensure the global uniqueness of URN namespaces, their identifiers (NIDs) are required to be registered with the IANA. Registered namespaces may be "formal" or "informal". An exception to the registration requirement was formerly made for "experimental namespaces",[8] since rescinded by RFC 8141.[1]

Formal

[edit]Approximately sixty formal URN namespace identifiers have been registered. These are namespaces where Internet users are expected to benefit from their publication,[1] and are subject to several restrictions. They must:

- Not be an already-registered NID

- Not start with

urn- - Be more than two letters long

- Not start with

XY-, where XY is any combination of two ASCII letters - Not start with

x-(see "Experimental namespaces", below)

Informal

[edit]Informal namespaces are registered with IANA and assigned a number sequence (chosen by IANA on a first-come-first-served basis) as an identifier,[1] in the format

"urn-" ⟨number⟩

Informal namespaces are fully fledged URN namespaces and can be registered in global registration services.[1]

Experimental

[edit]An exception to the registration requirement was formerly made for "experimental namespaces".[8] However, following the deprecation of the "X-" notation for new identifier names,[9] RFC 8141[1] did away with experimental URN namespaces, indicating a preference for use of the urn:example namespace where appropriate.[10]

Examples

[edit]| URN | corresponds to |

|---|---|

urn:isbn:0451450523

|

The 1968 book The Last Unicorn, identified by its International Standard Book Number. |

urn:isan:0000-0000-2CEA-0000-1-0000-0000-Y

|

The 2002 film Spider-Man, identified by its International Standard Audiovisual Number. |

urn:ISSN:0167-6423

|

The scientific journal Science of Computer Programming, identified by its International Standard Serial Number. |

urn:ietf:rfc:2648

|

The IETF's RFC 2648. |

urn:mpeg:mpeg7:schema:2001

|

The default namespace rules for MPEG-7 video metadata. |

urn:oid:2.16.840

|

The OID for the United States. |

urn:uuid:6e8bc430-9c3a-11d9-9669-0800200c9a66

|

A version 1 UUID. |

urn:nbn:de:bvb:19-146642

|

A National Bibliography Number for a document, indicating country (de), regional network (bvb = Bibliotheksverbund Bayern), library number (19) and document number.

|

urn:lex:eu:council:directive:2010-03-09;2010-19-UE

|

A directive of the European Union, using the proposed Lex URN namespace. |

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CDC8D258-8F57-41DC-B560-247E17D3DC8C

|

A Life Science Identifiers that may be resolved to http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CDC8D258-8F57-41DC-B560-247E17D3DC8C[permanent dead link] . |

urn:epc:class:lgtin:4012345.012345.998877

|

Global Trade Item Number with lot/batch number. As defined by Tag Data Standard[11] (TDS). See more examples at EPC Identification Keys. |

urn:epc:id:sgtin:0614141.112345.400

|

Global Trade Item Number with an individual serial number |

urn:epc:id:sscc:0614141.1234567890

|

Serial Shipping Container Code |

urn:epc:id:sgln:0614141.12345.400

|

Global Location Number with extension |

urn:epc:id:bic:CSQU3054383

|

BIC Intermodal container Code as per ISO 6346 |

urn:epc:id:imovn:9176187

|

IMO Vessel Number of marine vessels |

urn:epc:id:gdti:0614141.12345.400

|

Global Document Type Identifier of a document instance |

urn:mrn:iala:aton:us:1234.5

|

Identifier for Marine Aids to Navigation |

urn:mrn:iala:vts:ca:ecareg

|

Identifier for Vessel Traffic Services |

urn:mrn:iala:wwy:us:atl:chba:potri

|

Identifier for Waterways |

urn:mrn:iala:pub:g1143

|

Identifier for IALA publications |

urn:microsoft:adfs:claimsxray

|

Identifier for federated identity; this example is from Claims X-Ray[12] |

urn:eic:10X1001A1001A450

|

European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E), identified by its Energy Identification Code |

See also

[edit]- Archival Resource Key (ARK)

- .arpa – urn.arpa is for dynamic discovery

- Extensible resource identifier (XRI)

- Handle System

- Info URI scheme

- Life Science Identifiers (LSID)

- The Magnet URI scheme, which uses URNs

- Persistent Uniform Resource Locator (PURL)

- Tag URI scheme is like urn: in its URIs not being resource locators

- Digital Object Identifier (DOI)

- EPC Identification Keys.

- Maritime Resource Names (MRN)

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i RFC 8141 (2017).

- ^ RFC 1737 (1994).

- ^ RFC 2141 (1997).

- ^ a b W3C/IETF (2001).

- ^ a b RFC 3986 (2005).

- ^ RFC 6920 (2013).

- ^ RFC 8141, section 2 (2017).

- ^ a b RFC 3406 (2002).

- ^ RFC 6648 (2012).

- ^ RFC 6963 (2013).

- ^ "EPC Tag Data Standard, version 1.13". GS1. Nov 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ "Claims X-Ray AD FS Help".

Sources

[edit]- K. Sollins; L. Masinter (December 1994). Functional Requirements for Uniform Resource Names. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC1737. RFC 1737. Informational.

- R. Moats (May 1997). P. Vixie (ed.). URN Syntax. IETF Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC2141. RFC 2141. Proposed Standard. Obsoleted by RFC 8141.

- L. Daigle; D.W. van Gulik; R. Iannella; P. Faltstrom (October 2002). Uniform Resource Names (URN) Namespace Definition Mechanisms. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC3406. BCP 66. RFC 3406. Best Current Practice 66. Obsoleted by RFC 8141. Obsoletes RFC 2611.

- T. Berners-Lee; R. Fielding; L. Masinter (January 2005). Uniform Resource Identifier (URI): Generic Syntax. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC3986. STD 66. RFC 3986. Internet Standard 66. Obsoletes RFC 2732, 2396 and 1808. Updated by RFC 6874, 7320 and 8820. Updates RFC 1738.

- P. Saint-Andre; D. Crocker; M. Nottingham (June 2012). Deprecating the "X-" Prefix and Similar Constructs in Application Protocols. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC6648. ISSN 2070-1721. BCP 178. RFC 6648. Best Current Practice 178.

- S. Farrell; D. Kutscher; C. Dannewitz; B. Ohlman; A. Keranen; P. Hallam-Baker (April 2013). Naming Things with Hashes. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC6920. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 6920. Proposed Standard.

- P. Saint-Andre (May 2013). A Uniform Resource Name (URN) Namespace for Examples. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC6963. ISSN 2070-1721. BCP 183. RFC 6963. Best Current Practice 183. Updates RFC 1930.

- P. Saint-Andre; J. Klensin (April 2017). Uniform Resource Names (URNs). Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC8141. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 8141. Proposed Standard. Obsoletes RFC 2141, 3406.

- P. Saint-Andre; J. Klensin (April 2017). Uniform Resource Names (URNs). Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC8141. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 8141. Proposed Standard. sec. 2. Obsoletes RFC 2141, 3406.

§ 2. URN Syntax

- P. Saint-Andre; J. Klensin (April 2017). Uniform Resource Names (URNs). Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC8141. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 8141. Proposed Standard. sec. 2. Obsoletes RFC 2141, 3406.

- "Factsheet: DOI System and Internet Identifier Specifications". International DOI Foundation. October 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- W3C/IETF URI Planning Interest Group (21 September 2001). "URIs, URLs, and URNs: Clarifications and Recommendations 1.0". W3C. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

External links

[edit]- Official IANA Registry of URN Namespaces

- Uniform Resource Names working group at the IETF

- URNs and bibliographic citations in web authoring

- An example server-side URN resolver is described in RFC 2169.

Uniform Resource Name

View on Grokipediaurn:<NID>:<NSS>, where <NID> is a Namespace Identifier (e.g., "ISBN" for International Standard Book Number) and <NSS> is the Namespace-Specific String that provides the unique name within that namespace.[3] This structure allows URNs to encode diverse naming systems, such as ISBNs or UUIDs, into a common format while permitting optional components like resolution parameters (?+), resource parameters (?=), and fragments (#) for enhanced functionality.[1]

Over time, URN specifications evolved to address practical needs, with RFC 3406 (2002) introducing namespace definition mechanisms and RFC 8141 (April 2017) providing the current standard by obsoleting earlier documents and refining syntax, registration processes, and security considerations.[1] URN namespaces are managed through formal or informal registrations via the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), ensuring interoperability across applications like digital libraries, metadata systems, and device identification.[4] Key characteristics include case-insensitivity in the namespace identifier, support for hierarchical paths with slashes in the NSS, and a focus on persistence to avoid obsolescence, making URNs essential for long-lived digital resources.[1]

Definitions and Distinctions

Relation to URIs and URLs

A Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) serves as the overarching framework for identifying resources on the Internet, defined as a compact sequence of characters that identifies an abstract or physical resource using a generic syntax.[5] This specification, outlined in RFC 3986 (2005), encompasses both locators that provide mechanisms for accessing resources and names that ensure persistent identification, allowing for extensible naming schemes without implying a specific retrieval method.[6] A Uniform Resource Locator (URL) represents a subset of URIs that not only identifies a resource but also specifies its primary access mechanism and location, typically through schemes such as "http" or "ftp."[7] For example, a URL like "http://example.com/resource" indicates both the resource's identity and how to retrieve it via the HTTP protocol, distinguishing it from purely naming-focused identifiers.[8] In contrast, a Uniform Resource Name (URN) is a specific subset of URIs that employs the "urn" scheme to provide persistent, location-independent naming of resources within defined namespaces.[9] As detailed in RFC 8141 (2017), URNs prioritize global uniqueness and longevity over retrieval details, enabling stable references that do not change even if the resource's location varies.[10] Earlier conceptual distinctions often treated URIs, URLs, and URNs as parallel categories, with URLs for location and URNs for naming as separate from the broader URI umbrella, but this view has been deprecated in favor of a unified URI model where URLs and URNs are simply URI instances with particular semantics.[11] This clarification, provided in the W3C's 2001 note on URIs, URLs, and URNs, recommends using "URI" generically to avoid confusion and emphasizes that all such identifiers share the same syntactic foundation.[11] Historically, Uniform Resource Characteristics (URCs) were proposed as a complementary mechanism to URNs for carrying metadata about resources, but the initiative lacked sufficient adoption and was effectively abandoned.[12] This role has since been fulfilled by technologies like Resource Description Framework (RDF), which leverages URIs to describe and link metadata in a structured, web-scale manner.Purpose and Key Characteristics

The primary purpose of a Uniform Resource Name (URN) is to serve as a persistent, location-independent identifier for resources such as documents, individuals, or abstract concepts within distributed computing systems.[13] URNs enable the global naming of these resources without specifying how or where they can be accessed, focusing instead on stable identification that endures changes in technology or network structure.[9] This design supports applications requiring long-term referencing, such as academic citations or metadata management, by ensuring the name remains valid regardless of the resource's physical location or availability.[14] Key characteristics of URNs include their location independence, which decouples the identifier from any specific server, protocol, or retrieval method; permanence, as they are intended to outlast the lifecycle of the resource or issuing authority; global scope, achieved through structured namespaces that guarantee uniqueness across the internet; and resolvability, where the name can be mapped to locators, metadata, or services via namespace-specific mechanisms rather than direct dereferencing.[9] These attributes make URNs scalable for vast numbers of resources over extended periods, potentially spanning centuries, while supporting legacy identifier systems through extensible syntax.[13] For instance, URNs prioritize human readability with concise, case-insensitive strings that minimize special characters, facilitating transcription and interoperability.[14] Compared to Uniform Resource Locators (URLs), URNs offer advantages in resisting link rot, as their persistence avoids dependency on transient network addresses that may become obsolete when resources migrate or servers change.[9] This makes URNs particularly suitable for long-term referencing in scholarly or archival contexts, where URLs might fail due to evolving web infrastructure.[13] However, URNs have limitations, including a lack of inherent dereferenceability—unlike URLs, they do not directly enable resource retrieval and instead require additional resolution services provided by namespace authorities.[9] In the broader web architecture, URNs play a crucial role in enabling persistent identification for the semantic web, where they contribute to linking structured data across domains; digital libraries, supporting cataloging and replication of intellectual content; and established identifier systems like the International Standard Book Number (ISBN) and International Standard Serial Number (ISSN), which are integrated as URN namespaces for bibliographic resources.[15][14]Historical Development and Standards

Early Concepts and Initial RFCs

The concept of Uniform Resource Names (URNs) was first proposed in RFC 1630 (June 1994) by Tim Berners-Lee, introducing URIs as a unifying syntax, with URNs as persistent names distinct from URLs.[16] It emerged further in 1994 within the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) as part of early efforts to develop robust naming schemes for the evolving World Wide Web, specifically to overcome the limitations of Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) in providing persistent identification for resources that might change location or become unavailable. This proposal distinguished URNs as location-independent names from URLs, which primarily served as locators, aiming to enable stable referencing in a distributed Internet environment.[13] RFC 1737, published in December 1994, introduced URNs as a subtype of Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) and outlined their functional requirements, emphasizing global uniqueness, persistence, and scalability while providing a basic syntax framework that included a scheme identifier like "urn:" followed by namespace and resource-specific elements.[13] The document specified that URNs must support simple parsing, be transportable across Internet protocols, and accommodate legacy identifiers such as International Standard Book Numbers (ISBNs) to ensure backward compatibility.[13] Building on this foundation, RFC 2141, issued in May 1997, formalized the URN framework by defining a canonical syntax of "urn:Modern Updates and Current Specification

In 2005, RFC 3986 established the generic syntax for Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs), integrating Uniform Resource Names (URNs) as a specific URI scheme under "urn" within the broader URI framework, while maintaining the distinctions between URNs and Uniform Resource Locators (URLs). This standardization emphasized that URNs are location-independent identifiers, providing a unified parsing and resolution model that applies to all URI subtypes, including URNs.[5] RFC 8141, published in 2017, provided the current core specification for URNs by obsoleting RFC 2141 and refining the namespace definition process. Key updates include the introduction of an optional q-component (delimited by "?=") for parameters and an f-component (delimited by "#") for fragments to enhance URN expressiveness without altering the core structure, permission for unescaped forward slashes in the Namespace-Specific String (NSS) when they do not conflict with URI hierarchy, and the deprecation of experimental prefixes like "X-" to streamline formal registrations. These changes improve interoperability and flexibility in URN usage while maintaining persistence and global uniqueness.[9] The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) has maintained the URN Namespace Identifier (NID) registry since 1997, serving as the authoritative source for formal namespace assignments to prevent overlaps and ensure standardized identifiers. As of October 2025, the registry lists 92 formal URN namespaces, covering domains such as digital objects (e.g., "doi"), standards organizations (e.g., "ietf"), and industry-specific identifiers (e.g., "epc" for electronic product codes).[4] Post-2020 developments have focused on integrating URNs with emerging standards for persistence and interoperability, particularly in the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) system, where the "doi" namespace underpins long-term resource identification in scholarly publishing without major new RFCs. URNs continue to support semantic web ontologies by providing stable, namespace-bound identifiers for RDF resources, facilitating linked data in knowledge graphs. Additionally, URN concepts have seen increased adoption in blockchain-based decentralized identifiers (DIDs), which extend URI syntax—including URN-like persistence—for self-sovereign identity systems.[17][18] Current specifications exhibit gaps in addressing security concerns, such as potential namespace collisions from unregistered or legacy experimental identifiers, though the IANA registry mitigates this through formal review processes. Internationalization remains limited, relying primarily on percent-encoding for non-ASCII characters in line with URI rules, with no dedicated URN-specific updates beyond general Internationalized Resource Identifier (IRI) extensions in RFC 3987.Syntax and Components

Overall Structure

A Uniform Resource Name (URN) is structured as a sequence beginning with the fixed scheme identifier "urn:", followed by a Namespace Identifier (NID) and a Namespace-Specific String (NSS), collectively forming the general syntaxurn:NID:NSS.[1] This format ensures that URNs are globally unique and persistent identifiers, distinguishing them from locators like URLs.[1]

The syntax is formally defined using Augmented Backus-Naur Form (ABNF) in RFC 8141, where the core rule is assigned-name = "urn" ":" NID ":" NSS.[1] Here, NID consists of alphanumeric characters and hyphens, specifically matching the production (alphanum) 0*30(ldh) (alphanum) with ldh = alphanum / "-", limited to a maximum of 32 characters and prohibiting non-ASCII characters or trailing hyphens.[1] The NSS is defined as pchar *(pchar / "/"), where pchar includes unreserved, sub-delims, pct-encoded, and specific reserved characters, allowing for hierarchical path-like segments with forward slashes since the 2017 update.[1] Additional optional components, such as resolution (?+), query (?=), and fragment (#) parts, may append to the assigned-name but do not alter the core identifier.[1]

The scheme component is always "urn:", which is case-insensitive.[1] For encoding, special characters in the NID and NSS are represented using percent-encoding as per RFC 3986, where non-ASCII or reserved characters are encoded (e.g., a space as %20), and equivalence checks normalize percent-encoded octets to uppercase A-F.[1] Case normalization applies globally: the scheme and NID are converted to lowercase, while the NSS remains case-sensitive unless the namespace specifies otherwise.[1]

Validity requires that the NSS not be empty, the NID be a registered namespace, and the entire NSS conform to the rules of that namespace to enforce global uniqueness.[1] These rules prevent ambiguity and ensure syntactic well-formedness without embedding location information.[1]

Namespace Identifier and Namespace-Specific String

The Namespace Identifier (NID) is the initial component following the "urn:" scheme in a URN, serving to delineate a specific namespace that governs the interpretation and resolution of the identifier. It consists of an assigned string, such as "isbn" for International Standard Book Numbers or "uuid" for Universally Unique Identifiers, comprising 2 to 32 characters drawn from alphanumeric characters (a-z, 0-9) and hyphens.[19] NIDs must be registered with the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) through an Expert Review process to ensure global uniqueness and prevent conflicts, with fast-track options available for recognized standards development organizations.[4] By convention, NIDs are required to be in lowercase, and they explicitly exclude colons or any non-ASCII characters to maintain syntactic simplicity and compatibility with URI parsing rules.[20] The Namespace-Specific String (NSS) follows the NID, separated by a colon, and represents an opaque string that is unique within the defined namespace, carrying the core identifying information without inherent structure imposed by the URN syntax itself. For instance, in the "isbn" namespace, the NSS might encode a specific book's ISBN value, ensuring persistence and location independence.[21] Post-RFC 8141, the NSS may incorporate substructures such as hierarchical paths delimited by slashes ("/"). Optional components, such as a query component (q-component) prefixed with "?=" for namespace-specific parameters and a fragment component (f-component) starting with "#", may append after the assigned-name (including the NSS) for enhanced functionality.[22] Reserved characters within the NSS—such as semicolon (;), colon (:), question mark (?), at sign (@), equals (=), ampersand (&), plus (+), dollar ($), comma (,), square brackets ([]), and others from URI sub-delimiters—must be percent-encoded if intended as literal data, following UTF-8 encoding for any international or non-ASCII characters to preserve universality.[21] The NID and NSS interact modularly: the NID establishes the resolution rules and semantic context for the entire URN, such as mapping to metadata or locators via namespace-specific mechanisms, while the NSS provides the granular, unique identifier tailored to those rules.[23] This separation enables extensibility, as the NSS can imply hierarchical organization (e.g., through path-like segments) without prescribing the underlying access protocol, allowing flexible resolution across diverse systems like digital libraries or device registries.[24] Constraints on both components ensure syntactic robustness; for example, the absence of colons in the NID prevents ambiguity with the NSS delimiter, and the opacity of the NSS avoids assumptions about internal delimiters that could conflict with URI components.[19]Namespace Types

Formal Namespaces

Formal URN namespaces are officially registered collections of unique identifiers managed under the "urn" scheme, each associated with a specific Namespace Identifier (NID) assigned by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA).[1] These namespaces adhere to strict syntactic rules for the NID, which must consist of 1 to 31 case-insensitive alphanumeric characters and hyphens, starting and ending with an alphanumeric character, while avoiding reserved prefixes such as "urn-", "X-", or sequences like "AA-".[1] This formal registration ensures that NIDs are globally unique, persistent, and suitable for production use across the Internet, distinguishing them from provisional or experimental alternatives.[1] The registration process for formal URN namespaces follows the procedures outlined in RFC 8141, requiring submission of a detailed template to IANA via [email protected].[1] This template must demonstrate organizational stability, competence in identifier assignment, and a commitment to long-term persistence, with the proposal undergoing expert review by designated experts appointed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF).[1] The review evaluates uniqueness, interoperability potential, and alignment with URN goals, such as location independence and resolvability; only upon approval does IANA assign the NID and publish the namespace details in its official registry.[1] As of October 2025, IANA maintains 92 active formal URN namespaces.[4] Key examples of formal namespaces include "isbn" for International Standard Book Numbers, where the Namespace-Specific String (NSS) comprises a 10- or 13-digit ISBN code; "issn" for International Standard Serial Numbers, using an 8-character ISSN in the NSS; "doi" for Digital Object Identifiers, managed by the International DOI Foundation for scholarly resources; and "oid" for ASN.1 Object Identifiers, linking to ITU-T and ISO standards for hierarchical naming.[25][26][17] These namespaces exemplify standardized applications in publishing, digital objects, and telecommunications.[1] The primary benefits of formal namespaces lie in their promotion of interoperability and permanence, enabling consistent resolution and reference across diverse systems without reliance on transient locations.[1] They are integral to international standards, such as those from ISO for bibliographic and object identification, facilitating global resource discovery and citation.[1] IANA oversees maintenance through periodic registry updates, with ongoing additions and revisions but no fundamental changes to the core framework since the 2017 publication of RFC 8141.[4][1]Informal and Experimental Namespaces

Informal URN namespaces provide a mechanism for private or internal use without the full review process required for formal namespaces. These namespaces are identified by Namespace Identifiers (NIDs) that begin with "urn-" followed by a sequence of one or more digits, such as "urn-7", where the number starts with a non-zero digit and has no leading zeros.[27] IANA maintains a registry for these informal namespaces by assigning the next available number upon request, ensuring uniqueness without designating a specific community or enforcing detailed specifications.[27] This approach allows for quick allocation suitable for prototypes or temporary experiments, while still adhering to the overall URN syntax of "urn:NID:NSS", where NSS denotes the Namespace-Specific String.[28] Experimental URN namespaces, originally intended for trial and testing purposes, were denoted by NIDs prefixed with "X-", such as "urn:x-example". However, this category has been deprecated since RFC 6648, which removed the experimental designation to simplify namespace management and avoid potential conflicts. In its place, RFC 8141 recommends the use of the "example" namespace, registered as "urn:example", exclusively for documentation and illustrative purposes within RFCs and similar technical specifications.[29] This shift ensures that experimental constructs do not inadvertently enter production environments or collide with formally registered namespaces. Guidelines for these namespaces emphasize their role in non-permanent scenarios: informal namespaces are appropriate for internal prototypes and private testing, while the "urn:example" form is restricted to examples in standards documents to prevent real-world resolution attempts.[30] Both types are designed to avoid interference with formal namespaces by relying on IANA oversight for informal ones and strict documentation limits for experimental examples.[4] Limitations include their unsuitability for production deployment, as they lack the interoperability guarantees and resolution services associated with formal registration, potentially leading to issues in persistent identification or service discovery.[31] The evolution of these mechanisms reflects a post-2017 emphasis on encouraging formal registration for any namespace intended for long-term use, as outlined in RFC 8141, to promote stability and global consistency in URN adoption.[29] This update obsoletes earlier practices from RFC 2141 and related documents, prioritizing vetted namespaces to mitigate risks from ad-hoc identifiers.[32]Examples and Practical Applications

Illustrative URN Examples

A basic example of a URN utilizing the formal "ietf" namespace identifies an IETF document, such as an RFC. The stringurn:ietf:rfc:2648 consists of the namespace identifier (NID) "ietf" followed by the namespace-specific string (NSS) "rfc:2648", where "rfc" denotes the document type and "2648" is the specific identifier for the RFC defining the "ietf" namespace itself.[33]

Another illustrative URN employs the "isbn" namespace to reference a publication via its International Standard Book Number. The string urn:isbn:0-451-45052-3 features the NID "isbn" and an NSS comprising the 10-digit ISBN "0-451-45052-3" (including hyphens as separators for readability), which corresponds to Peter S. Beagle's novel The Last Unicorn. This format adheres to the syntax for ISBN-10 identifiers within the URN framework.[34]

For identifiers based on Universally Unique Identifiers (UUIDs), the "uuid" namespace provides a globally unique reference without relying on central authority. The example urn:uuid:6e8bc430-9c3a-11d9-9669-0800200c9a66 uses the NID "uuid" and an NSS that is the 128-bit UUID represented as a hyphenated hexadecimal string (version 1, time-based), ensuring uniqueness through timestamp and node components.

URNs may incorporate optional q-components (for query parameters) and f-components (for fragments) as defined in the updated specification, allowing additional context without altering the core identifier. An example is urn:example:resource?q=query#fragment, where "example" is the NID, "resource" forms the base NSS, "?q=query" adds a query parameter, and "#fragment" specifies a subpart; these components were formalized post-2017 to enhance flexibility while maintaining persistence.[1]

Informal URNs, intended for non-global or testing purposes, follow a simplified "urn-N" form where N indicates the version (typically 5 for ASCII). The string urn-5:local-id employs this structure with "5" denoting the encoding and "local-id" as a private identifier, suitable for internal systems without formal namespace registration.[1]

Use Cases Across Domains

In digital libraries, Uniform Resource Names (URNs) facilitate persistent access to scholarly resources through the Handle System, which assigns location-independent identifiers to digital objects such as journal articles. For instance, Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) are implemented as URNs in the formurn:doi:10.1000/xyz123, enabling stable resolution to content regardless of hosting changes and supporting interoperability across repositories. This approach has been integral to systems like CrossRef and PubMed Central, where over 390 million DOIs (as of January 2025) ensure long-term citation and retrieval of academic publications.[35][36]

URNs also underpin standards-based identifiers in publishing and scientific domains. The International Standard Book Number (ISBN) integrates with URNs via the namespace urn:isbn, allowing books to be uniquely named and resolved persistently, as specified in RFC 3187, which outlines the syntax for encoding ISBNs within the URN framework to support global bibliographic access. Similarly, the International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) uses urn:issn for periodicals, ensuring consistent identification of serial publications across libraries and databases. In biodiversity informatics, Life Science Identifiers (LSIDs) employ URNs like urn:lsid:authority:namespace:objectid:version to name biological entities such as species or specimens, promoting data sharing in repositories like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) by providing resolvable, non-hierarchical references that avoid duplication in taxonomic databases.[34][37][38]

Within supply chain management, URNs enable the Electronic Product Code (EPC) standard for tracking physical goods. EPCs are encoded as URNs, such as urn:epc:id:sgtin:0614141.107346.2017, which identify serialized items like consumer products in RFID-enabled logistics, facilitating real-time inventory and traceability from manufacturer to retailer as defined in RFC 5134. This namespace supports GS1 standards, allowing seamless integration with enterprise systems for applications in retail and pharmaceuticals, where accurate item-level identification reduces errors in global trade flows.[39]

Post-2020 developments have expanded URN applications in emerging technologies. In the semantic web, URNs serve as persistent identifiers within Resource Description Framework (RDF) graphs, linking distributed data sources by naming entities independently of their location, which enhances interoperability in knowledge bases like those used in linked open data projects. For blockchain-based assets, URNs incorporating Universally Unique Identifiers (UUIDs), such as urn:uuid:hex-string, provide stable naming for non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and digital collectibles, ensuring verifiable uniqueness without central authority as outlined in RFC 4122, though adoption remains experimental in decentralized ecosystems. In Internet of Things (IoT) contexts, RFC 9039 defines a URN namespace for device identifiers, such as urn:dev:mac:00-50-56-c0-00-01, enabling secure naming and discovery of connected hardware in smart grids and sensor networks, addressing scalability in edge computing environments.[40][41]

Despite these advantages, URN deployment faces challenges in resolution and security. Resolution often relies on Name Authority Pointer (NAPTR) DNS records to map URNs to locators, but inconsistent global infrastructure can lead to fragmented access, as NAPTR delegation requires coordinated namespace administration that is not universally implemented. Security vulnerabilities include phishing risks in informal namespaces, where malicious actors could register deceptive URNs to mimic legitimate resources, exploiting trust in persistent identifiers without inherent authentication mechanisms. Adoption barriers persist between Web 2.0 centralized platforms, which favor URLs for simplicity, and Web 3.0 decentralized systems, where URNs' persistence clashes with dynamic blockchain addressing, limiting widespread integration.[42]

Looking ahead, URNs hold potential in decentralized identity systems, where their location-independent design aligns with self-sovereign identity frameworks like Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs), which draw syntactic inspiration from URNs to enable verifiable, user-controlled digital credentials across blockchains and distributed ledgers. This evolution could bridge gaps in modern usage by enhancing interoperability in Web 3.0, supporting privacy-preserving applications in finance and healthcare while addressing scalability through hybrid resolution protocols.[18][43]