Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

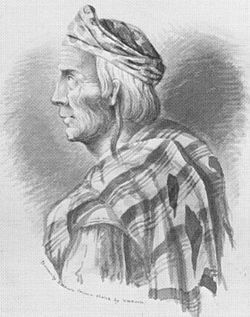

Narbona

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

Narbona or Hastiin Narbona (c. 1766 – August 31, 1849) was a Navajo chief who participated in the Navajo Wars. He was killed in a confrontation with U.S. soldiers on August 31, 1849.

Key Information

Narbona was one of the wealthiest Navajo of his time due to the number of sheep and horses owned by his extended family group. He was not a "chief" of all of the Navajo, as the independent minded Navajo had no central authority. However, he was very influential in the tribe due to the status gained from his wealth, personal reputation, and age during the time he negotiated with the white men.

Narbona became one of the most prominent tribal leaders after the massacre of 24 Navajo leaders in June, 1822 at Jemez Pueblo. They had been travelling under flag of truce to a peace conference with the New Mexican government.[1][2] In February 1835 he led the Navajo to a decisive victory in an ambush of a Mexican expedition in the Chuska Mountains led by Captain Blas de Hinojos. The site of the battle, Copper Pass (Béésh Łichííʼí Bigiizh), is now known as Narbona Pass.[2][3]

In 1849, Narbona, with several hundred of his warriors, rode to meet a delegation led by Col. John M. Washington to discuss peace terms between the Navajo and the "New Men", Americans who had driven the Mexicans from what is now the Southwestern United States. The U.S. party was composed of both U.S. Regulars and local New Mexican auxiliaries.

After several misunderstandings, translators managed to work out an acceptable list of terms for peace between the two parties. As the peace council broke up, Sadoval, a young Navajo warrior of some distinction, began riding his horse to and fro, exhorting the 200–300 Navajo warriors in attendance to break the new treaty immediately. At this point, a New Mexican officer claimed that he noticed a horse that belonged to him being ridden by one of the Navajo warriors. Washington, put in the position of backing one of his troopers, demanded that the horse be immediately turned over. The Navajo refused, and the horse and its rider departed.

Washington commanded his troops to unlimber their cannon and prepare to fire if the Navajo refused to return the, now absent, property the Americans said was stolen. The Navajo again denied his request, and the Americans opened fire with cannon as well as rifles.

Narbona was mortally wounded in the fusillade, and according to eyewitnesses, he was scalped by one of the New Mexico militiamen. He was buried by his sons in the traditional Navajo fashion, bound in a "death knotted" blanket and cast into a crevice. Two of his finest horses were slaughtered to ensure he would not walk to the afterlife.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Pages 67, 68, Sides, Blood and Thunder

- ^ a b Navajo Timeline 1821-1847

- ^ Pages 75-77, Sides, Blood and Thunder

References

[edit]- Sides, Hampton, Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West, Doubleday (2006), hardcover, 462 pages, ISBN 0-385-50777-1 ISBN 978-0-385-50777-6

- "Narbona", URL accessed 08/28/06 Archived 2006-10-22 at the Wayback Machine