Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Navajo language

View on WikipediaThis article should specify the language of its non-English content using {{lang}} or {{langx}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (October 2024) |

| Navajo | |

|---|---|

| Diné bizaad | |

| Native to | United States |

| Region | Arizona; New Mexico; Utah; Colorado |

| Ethnicity | 332,129 Navajo (2021) |

Native speakers | 170,000 (2019 census)[1] |

Dené–Yeniseian?

| |

| Latin (Navajo alphabet) Navajo Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Navajo Nation[2][3] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | nv |

| ISO 639-2 | nav |

| ISO 639-3 | nav |

| Glottolog | nava1243 |

| ELP | Diné Bizaad (Navajo) |

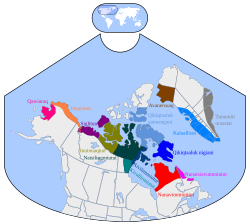

The Navajo Nation, where the language is most spoken | |

| People | Diné |

|---|---|

| Language | Diné Bizaad, Diné Yideez,[4] Hak'éí Yideez[5] |

| Country | Dinétah |

Navajo or Navaho (/ˈnævəhoʊ, ˈnɑːvə-/ NAV-ə-hoh, NAH-və-;[6] Navajo: Diné bizaad [tìnépìz̥ɑ̀ːt] or Naabeehó bizaad [nɑ̀ːpèːhópìz̥ɑ̀ːt]) is a Southern Athabaskan language of the Na-Dené family, through which it is related to languages spoken across the western areas of North America. Navajo is spoken primarily in the Southwestern United States, especially in the Navajo Nation. It is one of the most widely spoken Native American languages and is the most widely spoken north of the Mexico–United States border, with almost 170,000 Americans speaking Navajo at home as of 2011.

The language has struggled to keep a healthy speaker base, although this problem has been alleviated to some extent by extensive education programs in the Navajo Nation.[7] In World War II, speakers of the Navajo language joined the military and developed a code for sending secret messages. These code talkers' messages are widely credited with saving many lives and winning some of the most decisive battles in the war.

Navajo has a fairly large phonemic inventory, including several consonants that are not found in English. Its four basic vowel qualities are distinguished for nasality, length, and tone. Navajo has both agglutinative and fusional elements: it uses affixes to modify verbs, and nouns are typically created from multiple morphemes, but in both cases these morphemes are fused irregularly and beyond easy recognition. Basic word order is subject–object–verb, though it is highly flexible to pragmatic factors. Verbs are conjugated for aspect and mood, and given affixes for the person and number of both subjects and objects, as well as a host of other variables.

The language's orthography, which was developed in the late 1930s, is based on the Latin script. Most Navajo vocabulary is Athabaskan in origin, as the language has been conservative with loanwords due to its highly complex noun morphology.

Nomenclature

[edit]The word Navajo is an exonym: it comes from the Tewa word Navahu, which combines the roots nava ('field') and hu ('valley') to mean 'large field'. It was borrowed into Spanish to refer to an area of present-day northwestern New Mexico, and later into English for the Navajo tribe and their language.[8] The alternative spelling Navaho is considered antiquated; even the anthropologist Berard Haile spelled it with a "j" despite his personal objections.[9] The Navajo refer to themselves as the Diné ('People'), with their language known (its endonym) as Diné bizaad ('People's language')[10] or Naabeehó bizaad.

Classification

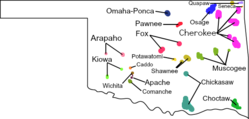

[edit]Navajo is an Athabaskan language; Navajo and Apache languages make up the southernmost branch of the family. Most of the other Athabaskan languages are located in Alaska, northwestern Canada, and along the North American Pacific coast.

Most languages in the Athabaskan family have tones. However, this feature evolved independently in all subgroups; Proto-Athabaskan had no tones.[11] In each case, tone evolved from glottalic consonants at the ends of morphemes; however, the progression of these consonants into tones has not been consistent, with some related morphemes being pronounced with high tones in some Athabaskan languages and low tones in others. It has been posited that Navajo and Chipewyan, which have no common ancestor more recent than Proto-Athabaskan and possess many pairs of corresponding but opposite tones, evolved from different dialects of Proto-Athabaskan that pronounced these glottalic consonants differently.[12] Proto-Athabaskan diverged fully into separate languages c. 500 BC.[13]

Navajo is most closely related to Western Apache, with which it shares a similar tonal scheme[14] and more than 92 percent of its vocabulary, and to Chiricahua-Mescalero Apache.[15][16] It is estimated that the Apachean linguistic groups separated and became established as distinct societies, of which the Navajo were one, somewhere between 1300 and 1525. Navajo is generally considered mutually intelligible with all other Apachean languages.[17]

History

[edit]

The Apachean languages, of which Navajo is one, are thought to have arrived in the American Southwest from the north by 1500, probably passing through Alberta and Wyoming.[18][19] Archaeological finds considered to be proto-Navajo have been located in the far northern New Mexico around the La Plata, Animas and Pine rivers, dating to around 1500. In 1936, linguist Edward Sapir showed how the arrival of the Navajo people in the new arid climate among the corn agriculturalists of the Pueblo area was reflected in their language by tracing the changing meanings of words from Proto-Athabaskan to Navajo. For example, the word *dè:, which in Proto-Athabaskan meant "horn" and "dipper made from animal horn", in Navajo became a-deeʼ, which meant "gourd" or "dipper made from gourd". Likewise, the Proto-Athabaskan word *ł-yəx̣s "snow lies on the ground" in Navajo became yas "snow". Similarly, the Navajo word for "corn" is naadą́ą́', derived from two Proto-Athabaskan roots meaning "enemy" and "food", suggesting that the Navajo originally considered corn to be "food of the enemy" when they first arrived among the Pueblo people.[20][21]

Navajo Code Talkers

[edit]

During World Wars I and II, the U.S. government employed speakers of the Navajo language as Navajo code talkers. These Navajo soldiers and sailors used a code based on the Navajo language to relay secret messages. At the end of the war the code remained unbroken.[22]

The code used Navajo words for each letter of the English alphabet. Messages could be encoded and decoded by using a simple substitution cipher where the ciphertext was the Navajo word. Type two code was informal and directly translated from English into Navajo. If there was no word in Navajo to describe a military word, code talkers used descriptive words. For example, the Navajo did not have a word for submarine, so they translated it as iron fish.[23][24]

These Navajo code talkers are widely recognized for their contributions to WWII. Major Howard Connor, 5th Marine Division Signal Officer stated, "Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima."[25]

Colonization

[edit]Navajo lands were initially colonized by the Spanish in the early seventeenth century, shortly after this area was annexed as part of the Spanish viceroyalty of New Spain. When the United States annexed these territories in 1848 following the Mexican–American War,[26] the English-speaking settlers allowed[citation needed] Navajo children to attend their schools. In some cases, the United States established separate schools for Navajo and other Native American children. In the late 19th century, it founded boarding schools, often operated by religious missionary groups. In efforts to acculturate the children, school authorities insisted that they learn to speak English and practice Christianity. Students routinely had their mouths washed out with lye soap as a punishment if they did speak Navajo.[27] Consequently, when these students grew up and had children of their own, they often did not teach them Navajo, in order to prevent them from being punished.[28]

Robert W. Young and William Morgan, who both worked for the Navajo Agency of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, developed and published a practical orthography in 1937. It helped spread education among Navajo speakers.[29] In 1943 the men collaborated on The Navajo Language, a dictionary organized by the roots of the language.[30] In World War II, the United States military used speakers of Navajo as code talkers—to transmit top-secret military messages over telephone and radio in a code based on Navajo. The language was considered ideal because of its grammar, which differs strongly from that of German and Japanese, and because no published Navajo dictionaries existed at the time.[31]

By the 1960s, Indigenous languages of the United States had been declining in use for some time. Native American language use began to decline more quickly in this decade as paved roads were built and English-language radio was broadcast to tribal areas. Navajo was no exception, although its large speaker pool—larger than that of any other Native language in the United States—gave it more staying power than most.[32] Adding to the language's decline, federal acts passed in the 1950s to increase educational opportunities for Navajo children had resulted in pervasive use of English in their schools.[33]

In more recent years, the number of monolingual Navajo speakers have been declining, and most younger Navajo people are bilingual.[34] Near the 1990s, many Navajo children have little to no knowledge in Navajo language, only knowing English.[35]

Revitalization and current status

[edit]In 1968, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Bilingual Education Act, which provided funds for educating young students who are not native English speakers. The Act had mainly been intended for Spanish-speaking children—particularly Mexican Americans—but it applied to all recognized linguistic minorities. Many Native American tribes seized the chance to establish their own bilingual education programs. However, qualified teachers who were fluent in Native languages were scarce, and these programs were largely unsuccessful.[32]

However, data collected in 1980 showed that 85 percent of Navajo first-graders were bilingual, compared to 62 percent of Navajo of all ages—early evidence of a resurgence of use of their traditional language among younger people.[36] In 1984, to counteract the language's historical decline, the Navajo Nation Council decreed that the Navajo language would be available and comprehensive for students of all grade levels in schools of the Navajo Nation.[32] This effort was aided by the fact that, largely due to the work of Young and Morgan, Navajo is one of the best-documented Native American languages. In 1980 they published a monumental expansion of their work on the language, organized by word (first initial of vowel or consonant) in the pattern of English dictionaries, as requested by Navajo students. The Navajo Language: A Grammar and Colloquial Dictionary also included a 400-page grammar, making it invaluable for both native speakers and students of the language. Particularly in its organization of verbs, it was oriented to Navajo speakers.[37] They expanded this work again in 1987, with several significant additions, and this edition continues to be used as an important text.[30]

The Native American language education movement has been met with adversity, such as by English-only campaigns in some areas in the late 1990s. However, Navajo-immersion programs have cropped up across the Navajo Nation. Statistical evidence shows that Navajo-immersion students generally do better on standardized tests than their counterparts educated only in English. Some educators have remarked that students who know their native languages feel a sense of pride and identity validation.[38] Since 1989, Diné College, a Navajo tribal community college, has offered an associate degree in the subject of Navajo.[39] This program includes language, literature, culture, medical terminology, and teaching courses and produces the highest number of Navajo teachers of any institution in the United States. About 600 students attend per semester.[40] One major university that teaches classes in the Navajo language is Arizona State University.[41] In 1992, Young and Morgan published another major work on Navajo: Analytical Lexicon of Navajo, with the assistance of Sally Midgette (Navajo). This work is organized by root, the basis of Athabaskan languages.[30]

A 1991 survey of 682 preschoolers on the Navajo Reservation Head Start program found that 54 percent were monolingual English speakers, 28 percent were bilingual in English and Navajo, and 18 percent spoke only Navajo. This study noted that while the preschool staff knew both languages, they spoke English to the children most of the time. In addition, most of the children's parents spoke to the children in English more often than in Navajo. The study concluded that the preschoolers were in "almost total immersion in English".[42] An American Community Survey taken in 2011 found that 169,369 Americans spoke Navajo at home—0.3 percent of Americans whose primary home language was not English. Of primary Navajo speakers, 78.8 percent reported they spoke English "very well", a fairly high percentage overall but less than among other Americans speaking a different Native American language (85.4 percent). Navajo was the only Native American language afforded its own category in the survey; domestic Navajo speakers represented 46.4 percent of all domestic Native language speakers (only 195,407 Americans have a different home Native language).[43] As of July 2014, Ethnologue classes Navajo as "6b" (In Trouble), signifying that few, but some, parents teach the language to their offspring and that concerted efforts at revitalization could easily protect the language. Navajo had a high population for a language in this category.[44] About half of all Navajo people live on Navajo Nation land, an area spanning parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah; others are dispersed throughout the United States.[26] Under tribal law, fluency in Navajo is mandatory for candidates to the office of the President of the Navajo Nation.[45]

Both original and translated media have been produced in Navajo. The first works tended to be religious texts translated by missionaries, including the Bible. From 1943 to about 1957, the Navajo Agency of the BIA published Ádahooníłígíí ("Events"[46]), the first newspaper in Navajo and the only one to be written entirely in Navajo. It was edited by Robert W. Young and William Morgan, Sr. (Navajo). They had collaborated on The Navajo Language, a major language dictionary published that same year, and continued to work on studying and documenting the language in major works for the next few decades.[30] Today an AM radio station, KTNN, broadcasts in Navajo and English, with programming including music and NFL games;[47] AM station KNDN broadcasts only in Navajo.[48] When Super Bowl XXX was broadcast in Navajo in 1996, it was the first time a Super Bowl had been carried in a Native American language.[49] In 2013, the 1977 film Star Wars was translated into Navajo. It was the first major motion picture translated into any Native American language.[50][51][52]

On October 5, 2018, an early beta of a Navajo course was released on Duolingo, a popular language learning app.[53]

On December 30, 2024, Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren made Navajo the official language of the Navajo Nation by signing legislation. He said, “One of my priorities coming in as President has always been to make sure that we make Navajo cool again.” This is in order to promote the intergenerational preservation of the Navajo language within the Navajo Nation and intending to work in conjunction with the Diné Language Teachers Association to foster the utilization of the Navajo language.[54]

Education

[edit]The Navajo Nation operates Tséhootsooí Diné Bi'ólta', a Navajo language immersion school for grades K-8 in Fort Defiance, Arizona. Located on the Arizona-New Mexico border in the southeastern quarter of the Navajo Reservation, the school strives to revitalize Navajo among children of the Window Rock Unified School District. Tséhootsooí Diné Bi'ólta' has thirteen Navajo language teachers who instruct only in the Navajo language, and no English, while five English language teachers instruct in the English language. Kindergarten and first grade are taught completely in the Navajo language, while English is incorporated into the program during third grade, when it is used for about 10% of instruction.[55] In the 2020s, the language nest Saad K’ildyé was established near Albuquerque through a non-profit Diné-led organization. The school also offers classes to parents and family activities revolving around Diné culture.

After many Navajo schools were closed during World War II, a program aiming to provide education to Navajo children was funded in the 1950s, where the number of students quickly doubled in the next decade.[35] According to the Navajo Nation Education Policies, the Navajo Tribal Council requests that schools teach both English and Navajo so that the children would remain bilingual, though their influence over the school systems was very low.[35] A small number of preschool programs provide a Navajo-language immersion curriculum, which teaches children basic Navajo vocabulary and grammar under the assumption that they have no prior knowledge in the Navajo language.[35]

Phonology

[edit]Navajo has a fairly large consonant inventory. Its stop consonants exist in three laryngeal forms: aspirated, unaspirated, and ejective—for example, /tʃʰ/, /tʃ/, and /tʃʼ/.[56] Ejective consonants are those that are pronounced with a glottalic initiation. Navajo also has a simple glottal stop used after vowels,[57] and every word that would otherwise begin with a vowel is pronounced with an initial glottal stop.[58] Consonant clusters are uncommon, aside from frequent placing /d/ or /t/ before fricatives.[59]

The language has four vowel qualities: /a/, /e/, /i/, and /o/.[59] Each exists in both oral and nasalized forms, and can be either short or long.[60] Navajo also distinguishes for tone between high and low, with the low tone typically regarded as the default. However, some linguists have suggested that Navajo does not possess true tones, but only a pitch accent system similar to that of Japanese.[61] In general, Navajo speech also has a slower speech tempo than English does.[57]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palato- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lateral | fricated | plain | lab. | plain | lab. | ||||||

| Obstruent | Stop | unaspirated | p | t | tˡ | ts | tʃ | k | ʔ | |||

| aspirated | tʰ | tɬʰ | tsʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | (kʷʰ) | ||||||

| ejective | tʼ | tɬʼ | tsʼ | tʃʼ | kʼ | |||||||

| Continuant | fortis | ɬ | s | ʃ | x | (xʷ) | (h) | (hʷ) | ||||

| lenis | l | z | ʒ | ɣ | (ɣʷ) | |||||||

| Sonorant | plain | m | n | j | (w) | |||||||

| glottalized | (mˀ) | (nˀ) | (jˀ) | (wˀ) | ||||||||

| Vowel height | Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | oral | nasal | |

| High | ɪ / iː | ɪ̃ / ĩː | ||

| Mid | ɛ / eː | ɛ̃ / ẽː | ɔ~ɞ / oː | õ / õː |

| Low | ɑ / ɑː | ɑ̃ / ɑ̃ː | ||

Grammar

[edit]Typology

[edit]Navajo is difficult to classify in terms of broad morphological typology: it relies heavily on affixes—mainly prefixes—like agglutinative languages,[62] but these affixes are joined in unpredictable, overlapping ways that make them difficult to segment, a trait of fusional languages.[63] In general, Navajo verbs contain more morphemes than nouns do (on average, 11 for verbs compared to 4–5 for nouns), but noun morphology is less transparent.[64] Depending on the source, Navajo is either classified as a fusional,[63][65] agglutinative, or even polysynthetic language, as it shows mechanisms from all three.[28][66]

In terms of basic word order, Navajo has been classified as a subject–object–verb language.[67][68] However, some speakers order the subject and object based on "noun ranking". In this system, nouns are ranked in three categories—humans, animals, and inanimate objects—and within these categories, nouns are ranked by strength, size, and intelligence. Whichever of the subject and object has a higher rank comes first. As a result, the agent of an action may be syntactically ambiguous.[69] The highest rank position is held by humans and lightning.[70] Other linguists such as Eloise Jelinek consider Navajo to be a discourse configurational language, in which word order is not fixed by syntactic rules, but determined by pragmatic factors in the communicative context.[71]

Verbs

[edit]In Navajo, verbs are the main elements of their sentences, imparting a large amount of information. The verb is based on a stem, which is made of a root to identify the action and the semblance of a suffix to convey mode and aspect; however, this suffix is fused beyond separability.[72] The stem is given somewhat more transparent prefixes to indicate, in this order, the following information: postpositional object, postposition, adverb-state, iterativity, number, direct object, deictic information, another adverb-state, mode and aspect, subject, classifier (see later on), mirativity and two-tier evidentiality. Some of these prefixes may be null; for example, there is only a plural marker (da/daa) and no readily identifiable marker for the other grammatical numbers.[73]

Navajo does not distinguish strict tense per se; instead, an action's position in time is conveyed through mode, aspect, but also via time adverbials or context. Each verb has an inherent aspect and can be conjugated in up to seven modes.[74]

For any verb, the usitative and iterative modes share the same stem, as do the progressive and future modes; these modes are distinguished with prefixes. However, pairs of modes other than these may also share the same stem,[75] as illustrated in the following example, where the verb "to play" is conjugated into each of the five mode paradigms:

- Imperfective: -né – is playing, was playing, will be playing

- Perfective: -neʼ – played, had played, will have played

- Progressive/future: -neeł – is playing along / will play, will be playing

- Usitative/iterative: -neeh – usually plays, frequently plays, repeatedly plays

- Optative: -neʼ – would play, may play

The basic set of subject prefixes for the imperfective mode, as well as the actual conjugation of the verb into these person and number categories, are as follows.[76]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The remaining piece of these conjugated verbs—the prefix na- —is called an "outer" or "disjunct" prefix. It is the marker of the Continuative aspect (to play about).[77]

Navajo distinguishes between the first, second, third, and fourth persons in the singular, dual, and plural numbers.[78] The fourth person is similar to the third person, but is generally used for indefinite, theoretical actors rather than defined ones.[79] Despite the potential for extreme verb complexity, only the mode/aspect, subject, classifier, and stem are absolutely necessary.[73] Furthermore, Navajo negates clauses by surrounding the verb with the circumclitic doo= ... =da (e.g. mósí doo nitsaa da 'the cat is not big'). Dooda, as a single word, corresponds to English no.[80]

Nouns

[edit]Nouns are not required in order to form a complete Navajo sentence. Besides the extensive information that can be communicated with a verb, Navajo speakers may alternate between the third and fourth person to distinguish between two already specified actors, similarly to how speakers of languages with grammatical gender may repeatedly use pronouns.[81]

Most nouns are not inflected for number,[80] and plurality is usually encoded directly in the verb through the use of various prefixes or aspects, though this is by no means mandatory. In the following example, the verb on the right is used with the plural prefix da- and switches to the distributive aspect.

Some verbal roots encode number in their lexical definition (see classificatory verbs above). When available, the use of the correct verbal root is mandatory:

Béégashii

cow

sitį́.

3.SUBJ-lie(1).PERF

'The (one) cow lies.'

Béégashii

cow

shitéézh.

3.SUBJ-lie(2).PERF

'The (two) cows lie.'

Béégashii

cow

shijééʼ.

3.SUBJ-lie(3+).PERF

'The (three or more) cows lie.'

Bilasáana

bilasáana

apple

shaa

sh-aa

1-to

niʼaah.

Ø-ni-ʼaah

3.OBJ-2.SUBJ-give(SRO).MOM.PERF

'You give me an apple.'

Bilasáana

bilasáana

apple

shaa

sh-aa

1-to

ninííł.

Ø-ni-nííł

3.OBJ-2.SUBJ-give(PLO1).MOM.PERF

'You give me apples.'

Number marking on nouns occurs only for terms of kinship and age-sex groupings. Other prefixes that can be added to nouns include possessive markers (e.g., chidí 'car' – shichidí 'my car') and a few adjectival enclitics. Generally, an upper limit for prefixes on a noun is about four or five.[82]

Nouns are also not marked for case, this traditionally being covered by word order.[83]

Atʼééd

girl

ashkii

boy

yiyiiłtsą́.

3.OBJ-3.SUBJ-saw

'The girl saw the boy.'

Ashkii

boy

atʼééd

girl

yiyiiłtsą́.

3.OBJ-3.SUBJ-saw

'The boy saw the girl.'

Vocabulary

[edit]The vast majority of Navajo vocabulary is of Athabaskan origin.[84] The number of lexical roots is still fairly small; one estimate counted 6,245 noun bases and 9,000 verb bases (with most nouns being derived from verbs), but those are combined with the numerous affixes in a myriad of ways so that words rarely consist of a single stem like English.[82] Prior to the European colonization of the Americas, Navajo did not borrow much from other languages, including from other Athabaskan and even Apachean languages. The Athabaskan family is fairly diverse in both phonology and morphology due to its languages' prolonged relative isolation.[84] Even the Pueblo peoples, with whom the Navajo interacted with for centuries and borrowed cultural customs, have lent few words to the Navajo language. After Spain and Mexico took over Navajo lands, the language did not incorporate many Spanish words, either.[85]

This resistance to word absorption extended to English, at least until the mid-twentieth century. Around this point, the Navajo language began importing some, though still not many, English words, mainly by young schoolchildren exposed to English.[33]

Navajo has expanded its vocabulary to include Western technological and cultural terms through calques and Navajo descriptive terms. For example, the phrase for English tank is chidí naaʼnaʼí beeʼeldǫǫhtsoh bikááʼ dah naaznilígíí 'vehicle that crawls around, by means of which big explosions are made, and that one sits on at an elevation'. This language purism also extends to proper nouns,[citation needed] such as the names of U.S. states (e.g. Hoozdo 'Arizona' and Yootó 'New Mexico'; see also hahoodzo 'state') and languages (naakaii 'Spanish').

Only one Navajo word has been fully absorbed into the English language: hogan (from Navajo hooghan) – a term referring to the traditional houses.[86] Another word with limited English recognition is chindi (an evil spirit of the deceased).[87] The taxonomic genus name Uta may be of Navajo origin.[88] It has been speculated that English-speaking settlers were reluctant to take on more Navajo loanwords compared to many other Native American languages, including the Hopi language, because the Navajo were among the most violent resisters to colonialism.[89]

Orthography

[edit]Early attempts at a Navajo orthography were made in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One such attempt was based on the Latin alphabet, particularly the English variety, with some additional letters and diacritics. Anthropologists were frustrated by Navajo's having several sounds that are not found in English and lack of other sounds that are.[90] Finally, the current Navajo orthography was developed between 1935 and 1940[29] by Young and Morgan.

| Navajo Orthography | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʼ ʔ |

a ɑ |

á ɑ́ |

ą ɑ̃ |

ą́ ɑ̃́ |

aa ɑː |

áá ɑ́ː |

ąą ɑ̃ː |

ą́ą́ ɑ̃́ː |

b p |

ch tʃʰ |

chʼ tʃʼ |

d t |

dl tˡ |

dz ts |

e e |

| é é |

ę ẽ |

ę́ ẽ́ |

ee eː |

éé éː |

ęę ẽː |

ę́ę́ ẽ́ː |

g k |

gh ɣ |

h h/x |

hw hʷ/xʷ |

i ɪ |

í ɪ́ |

į ɪ̃ |

į́ ɪ̃́ |

ii ɪː |

| íí ɪ́ː |

įį ɪ̃ː |

į́į́ ɪ̃́ː |

j tʃ |

k kʰ/kx |

kʼ kʼ |

kw kʰʷ/kxʷ |

l l |

ł ɬ |

m m |

n n |

o o |

ó ó |

ǫ õ |

ǫ́ ṍ |

oo oː |

| óó óː |

ǫǫ õː |

ǫ́ǫ́ ṍː |

s s |

sh ʃ |

t tʰ/tx |

tʼ tʼ |

tł tɬʰ |

tłʼ tɬʼ |

ts tsʰ |

tsʼ tsʼ |

w w/ɣʷ |

x h/x |

y j/ʝ |

z z |

zh ʒ |

An apostrophe (ʼ) is used to mark ejective consonants (e.g. chʼ, tłʼ)[91] as well as mid-word or final glottal stops. However, initial glottal stops are usually not marked.[58]

The voiceless glottal fricative (/h/) is normally written as h, but appears as x after the consonant s (optionally after sh) at syllable boundary (ex: yiyiis-xı̨́), and when it represents the depreciative augment found after stem initial (ex: tsxı̨́įł-go, yi-chxa).[91][92] The voiced velar fricative is written as y before i and e (where it is palatalized /ʝ/), as w before o (where it is labialized /ɣʷ/), and as gh before a.[93]

Navajo represents nasalized vowels with an ogonek ( ˛ ), sometimes described as a reverse cedilla; and represents the voiceless alveolar lateral fricative (/ɬ/) with a barred L (capital Ł, lowercase ł).[94] The ogonek is most often placed centrally under a vowel[citation needed], but it was imported from Polish and Lithuanian, which do not usually center it nor use it under certain vowels such as o or any vowels with accent marks. For example, in Navajo works, the ogonek below lowercase a is most often shown centered below the letter, whereas fonts with a with ogonek intended for Polish and Lithuanian have its ogonek connected to the bottom right of the letter. Very few Unicode fonts display the ogonek differently in Navajo with language tagging than in Polish or Lithuanian.

The first Navajo-capable typewriter was developed in preparation for a Navajo newspaper and dictionary created in the 1940s. The advent of early computers in the 1960s necessitated special fonts to input Navajo text, and the first Navajo font was created in the 1970s.[94] Navajo virtual keyboards were made available for iOS devices in November 2012 and Android devices in August 2013.[95]

Sample text

[edit]This is the first paragraph of a Navajo short story.[96]

Navajo original: Ashiiké tʼóó diigis léiʼ tółikaní łaʼ ádiilnííł dóó nihaa nahidoonih níigo yee hodeezʼą́ jiní. Áko tʼáá ałʼąą chʼil naʼatłʼoʼii kʼiidiilá dóó hááhgóóshį́į́ yinaalnishgo tʼáá áłah chʼil naʼatłʼoʼii néineestʼą́ jiní. Áádóó tółikaní áyiilaago tʼáá bíhígíí tʼáá ałʼąą tłʼízíkágí yiiʼ haidééłbįįd jiní. "Háadida díí tółikaní yígíí doo łaʼ ahaʼdiidził da," níigo ahaʼdeetʼą́ jiníʼ. Áádóó baa nahidoonih biniiyé kintahgóó dah yidiiłjid jiníʼ (...)

English translation: Some crazy boys decided to make some wine to sell, so they each planted grapevines and, working hard on them, they raised them to maturity. Then, having made wine, they each filled a goatskin with it. They agreed that at no time would they give each other a drink of it, and they then set out for town lugging the goatskins on their backs (...)

See also

[edit]- Navajo Nation – Federally recognized tribe in the Southwest United States

Citations

[edit]- ^ Navajo at Ethnologue (24th ed., 2021)

- ^ "'Make Navajo cool again': Diné Bizaad adopted as Navajo Nation's official language". 30 December 2024.

- ^ "Diné Bizaad becomes the official language of Navajo Nation". 30 December 2024.

- ^ Wall, Leon; Morgan, William (1958). Navajo–English Dictionary. p. 63. Retrieved 26 March 2025.

- ^ Wall & Morgan (1958), p. 34.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ^ O'Neill, Sean (2025-02-19), "Extinctions: Language Death, Intangible Cultural Heritage, and Early 21st-Century Renewal Efforts", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1241, ISBN 978-0-19-022861-3, retrieved 2025-11-11

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Navajo". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ Bahr 2004, p. xxxv

- ^ Minahan 2013, p. 260

- ^ Hargus & Rice 2005, p. 139

- ^ Hargus & Rice 2005, p. 138

- ^ Johansen & Ritzker 2007, p. 333

- ^ Hargus & Rice 2005, p. 209

- ^ Levy 1998, p. 25

- ^ Johansen & Ritzker 2007, p. 334

- ^ Koenig 2005, p. 9

- ^ Perry, Richard J. (November 1980). "The Apachean Transition from the Subarctic to the Southwest". Plains Anthropologist. 25 (90): 279–296. doi:10.1080/2052546.1980.11908999.

- ^ Brugge, D. M. (1983). "Navajo prehistory and history to 1850". Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 10. Smithsonian. pp. 489–501. ISBN 978-0-16-004579-0.

- ^ Sapir, E. (1936). "Internal linguistic evidence suggestive of the northern origin of the Navaho". American Anthropologist, 38(2), 224–235.

- ^ Shaul, D. L. (2014). A Prehistory of Western North America: The Impact of Uto-Aztecan Languages. UNM Press. [ISBN missing]

- ^ "1942: Navajo Code Talkers". United States Intelligence Community. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019.

- ^ "Code Talking – Native Words Native Warriors". americanindian.si.edu. Archived from the original on January 12, 2019. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- ^ "American Indian Code Talkers". The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. Archived from the original on January 27, 2019. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- ^ "Language Spotlight: Navajo". 25 September 2013.

- ^ a b Minahan 2013, p. 261

- ^ "The Warrior Tradition | The Warrior Tradition". Archived from the original on 2019-11-15. Retrieved 2020-03-13 – via www.pbs.org.

- ^ a b Johansen & Ritzker 2007, p. 421

- ^ a b Minahan 2013, p. 262

- ^ a b c d Hargus, Sharon; Morgan, William (1996). "Review of Analytical Lexicon of Navajo, William Morgan Sr". Anthropological Linguistics. 38 (2): 366–370. JSTOR 30028936.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (6 June 2014). "Chester Nez, 93, Dies; Navajo Words Washed From Mouth Helped Win War". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Johansen & Ritzker 2007, p. 422

- ^ a b Kroskrity & Field 2009, p. 38

- ^ LEE, LLOYD L. (2020). Diné Identity in a Twenty-First-Century World. University of Arizona Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11sn6g4. ISBN 978-0-8165-4068-6. JSTOR j.ctv11sn6g4. S2CID 219444542. Project MUSE book 75750.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d Spolsky, Bernard (June 2002). "Prospects for the Survival of the Navajo Language: A Reconsideration". Anthropology and Education Quarterly. 33 (2): 139–162. doi:10.1525/aeq.2002.33.2.139. ProQuest 218107198.

- ^ Koenig 2005, p. 8

- ^ Kari, James; Leer, Jeff (1984). "Review of The Navajo Language: A Grammar and Colloquial Dictionary". International Journal of American Linguistics. 50 (1): 124–130. doi:10.1086/465821. JSTOR 1265203.

- ^ Johansen & Ritzker 2007, pp. 423–424

- ^ Young & Elinek 1996, p. 376

- ^ Young & Elinek 1996, pp. 377–385

- ^ Arizona State University News (May 3, 2014). "Learning Navajo Helps Students Connect to Their Culture". Indian Country (Today Media Network). Archived from the original on May 20, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Platero & Hinton 2001, pp. 87–97

- ^ Ryan, Camille (August 2013). "Language Use" (PDF). Census.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ "Navajo in the Language Cloud". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ Fonseca, Felicia (September 11, 2014). "Language factors into race for Navajo president". The Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ Teresa L. McCarty (2002). A Place to Be Navajo: Rough Rock and the Struggle for Self-Determination in Indigenous Schooling. Routledge. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-1-135-65158-9. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ "Raiders vs Lions to be Broadcast in Navajo". Raiders.com. December 14, 2011. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Kane, Jenny (January 28, 2013). "Watching the ancient Navajo language develop in a modern culture". Carlsbad Current-Argus. Carlsbad, New Mexico. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ "Super Bowl carried in Navajo language". The Post and Courier: 3B. January 19, 1996.

- ^ Trudeau, Christine (June 20, 2013). "Translated Into Navajo, 'Star Wars' Will Be". NPR. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Silversmith, Shondiin (July 4, 2013). "Navajo Star Wars a crowd pleaser". Navajo Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Riley, Kiera. "Dubbing 'Star Wars: A New Hope' into Navajo language". Cronkite News. Retrieved 20 March 2025.

- ^ "Duolingo". www.duolingo.com. Archived from the original on 2018-10-06. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- ^ Staff, Native News Online (2024-12-30). "Diné Bizaad Becomes the Official Language of Navajo Nation". Native News Online. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ "Tséhootsooí Diné Bi'óta' Navaho Immersion School". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ McDonough 2003, p. 3

- ^ a b Kozak 2013, p. 162

- ^ a b Faltz 1998, p. 3

- ^ a b McDonough 2003, p. 5

- ^ McDonough 2003, pp. 6–7

- ^ Yip 2002, p. 239

- ^ Young & Morgan 1992, p. 841

- ^ a b Mithun 2001, p. 323

- ^ Bowerman & Levinson 2001, p. 239

- ^ Sloane 2001, p. 442

- ^ Bowerman & Levinson 2001, p. 238

- ^ "Datapoint Navajo / Order of Subject, Object and Verb". WALS. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ Tomlin, Russell S. (2014). "Basic Word Order: Functional Principles". Routledge Library Editions Linguistics B: Grammar: 115.

- ^ Young & Morgan 1992, pp. 902–903

- ^ Young & Morgan 1987, pp. 85–86

- ^ Fernald & Platero 2000, pp. 252–287

- ^ Eddington, David; Lachler, Jordan (2010). "A computational analysis of Navajo verb stems" (PDF). In Rice, Sally; Newman, John (eds.). Empirical and Experimental Methods in Cognitive/functional Research. CSLI Publications/Center for the Study of Language and Information. ISBN 978-1-57586-612-3.

- ^ a b McDonough 2003, pp. 21–22

- ^ Young & Morgan 1992, p. 868

- ^ Faltz 1998, p. 18

- ^ Faltz 1998, pp. 21–22

- ^ Faltz 1998, pp. 12–13

- ^ Faltz 1998, p. 21

- ^ Akmajian, Adrian; Anderson, Stephen (January 1970). "On the use of the fourth person in Navajo, or Navajo made harder". International Journal of American Linguistics. 36 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1086/465082. S2CID 143473426.

- ^ a b Young & Morgan 1992, p. 882

- ^ Kozak 2013, p. 161

- ^ a b Mueller-Gathercole 2008, p. 12

- ^ Speas 1990, p. 203

- ^ a b Wurm, Mühlhäusler & Tyron 1996, p. 1134

- ^ Kroskrity & Field 2009, p. 39

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "hogan". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on August 11, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ Cutler 2000, p. 165

- ^ Cutler 2000, p. 211

- ^ Cutler 2000, p. 110

- ^ Bahr 2004, pp. 33–34

- ^ a b Faltz 1998, p. 5

- ^ McDonough 2003, p. 85

- ^ McDonough 2003, p. 160

- ^ a b Spolsky 2009, p. 86

- ^ "Navajo Keyboard Now Available on Android Devices!". Indian Country (Today Media Network). September 12, 2013. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Young & Morgan 1987, pp. 205a–205b

General and cited references

[edit]- Bahr, Howard M. (2004). The Navajo as Seen by the Franciscans, 1898–1921: A Sourcebook. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4962-4.

- Beck, David (2006). Aspects of the Theory of Morphology. Vol. 10. Walter De Gruyter.

- Bowerman, Melissa; Levinson, Stephen (2001). Language Acquisition and Conceptual Development. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59659-6.

- Christiansen, Morten H. (2009). Language Universals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-30543-2.

- Cutler, Charles L. (2000). O Brave New Words: Native American Loanwords in Current English. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3246-4.

- Faltz, Leonard M. (1998). The Navajo Verb: A Grammar for Students and Scholars. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-1902-9.

- Fernald, Theodore; Platero, Paul (2000). The Athabaskan Languages: Perspectives on a Native American Language Family. Oxford University Press. pp. 252–287. ISBN 978-0195119473.

- Mueller-Gathercole, Virginia C. (2008). Routes to Language: Studies in Honor of Melissa Bowerman. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-841-69716-1.

- Hargus, Sharon; Rice, Keren (2005). Athabaskan Prosody. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-4783-4.

- Johansen, Bruce; Ritzker, Barry (2007). Encyclopedia of American Indian History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-817-0.

- Koenig, Harriet (2005). Acculturation in the Navajo Eden: New Mexico, 1550–1750: Archaeology, Language, Religion of the Peoples of the Southwest. YBK Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-9764359-1-4.

- Luraghi, Silvia; Parodi, Claudia (2013). The Bloomsbury Companion to Syntax. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-441-12460-9.

- Kroskrity, Paul V.; Field, Margaret C. (2009). Native American Language Ideologies: Beliefs, Practices, and Struggles in Indian Country. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-2916-2.

- Levy, Jerrold E. (1998). In the Beginning: The Navajo Genesis. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21277-0.

- McDonough, J.M. (2003). The Navajo Sound System. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4020-1351-5.

- Kozak, David L. (2013). Inside Dazzling Mountains: Southwest Native Verbal Arts. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1575-7.

- Minahan, James (2013). Ethnic Groups of the Americas: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-163-5.

- Mithun, Marianne (2001). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29875-9.

- Platero, Paul; Hinton, Leanne (2001). The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice. Academic Press. ISBN 978-90-04-25449-7.

- Sloane, Thomas O. (2001). Encyclopedia of Rhetoric. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512595-5.

- Speas, Margaret (1990). Phrase Structure in Natural Language. Springer. ISBN 978-0-792-30755-6.

- Spolsky, Bernard (2009). Language Management. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-73597-1.

- Wurm, Stephen A.; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tyron, Darrell T. (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

- Yip, Moira (2002). Tone. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77445-1.

- Young, Robert; Morgan, William Sr. (1987). The Navajo Language: A Grammar and Colloquial Dictionary. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-1014-9.

- Young, Robert; Morgan, William Sr. (1992). Analytical Lexicon of Navajo. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-1356-0.

- Young, Robert M.; Elinek, Eloise (1996). Athabaskan Language Studies (in English and Navajo). University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-1705-6.

Further reading

[edit]Educational

[edit]- Blair, Robert W.; Simmons, Leon; Witherspoon, Gary (1969). Navaho Basic Course. Brigham Young University Printing Services.

- "E-books for children with narration in Navajo". Unite for Literacy library. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- Goossen, Irvy W. (1967). Navajo made easier: A course in conversational Navajo. Flagstaff, AZ: Northland Press.

- Goossen, Irvy W. (1995). Diné bizaad: Speak, read, write Navajo. Flagstaff, AZ: Salina Bookshelf. ISBN 0-9644189-1-6.

- Goossen, Irvy W. (1997). Diné bizaad: Sprechen, Lesen und Schreiben Sie Navajo. Translated by Loder, P. B. Flagstaff, AZ: Salina Bookshelf.

- Haile, Berard. (1941–1948). Learning Navaho, (Vols. 1–4). St. Michaels, AZ: St. Michael's Mission.

- Platero, Paul R. (1986). Diné bizaad bee naadzo: A conversational Navajo text for secondary schools, colleges and adults. Farmington, NM: Navajo Preparatory School.

- Platero, Paul R.; Legah, Lorene; Platero, Linda S. (1985). Diné bizaad bee naʼadzo: A Navajo language literacy and grammar text. Farmington, NM: Navajo Language Institute.

- Tapahonso, Luci; Schick, Eleanor (1995). Navajo ABC: A Diné alphabet book. New York: Macmillan Books for Young Readers. ISBN 0-689-80316-8.

- Witherspoon, Gary (1985). Diné Bizaad Bóhooʼaah for secondary schools, colleges, and adults. Farmington, NM: Navajo Language Institute.

- Witherspoon, Gary (1986). Diné Bizaad Bóhooʼaah I: A conversational Navajo text for secondary schools, colleges and adults. Farmington, NM: Navajo Language Institute.

- Wilson, Alan (1969). Breakthrough Navajo: An introductory course. Gallup, NM: University of New Mexico.

- Wilson, Alan (1970). Laughter, the Navajo way. Gallup, NM: University of New Mexico.

- Wilson, Alan (1978). Speak Navajo: An intermediate text in communication. Gallup, NM: University of New Mexico.

- Wilson, Garth A. (1995). Conversational Navajo workbook: An introductory course for non-native speakers. Blanding, UT: Conversational Navajo Publications. ISBN 0-938717-54-5.

- Yazzie, Evangeline Parsons; Speas, Margaret (2008). Diné Bizaad Bínáhoo'aah: Rediscovering the Navajo Language. Flagstaff, AZ: Salina Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-893354-73-9.

- Yazzie, Sheldon A. (2005). Navajo for Beginners and Elementary Students. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Linguistics and other reference

[edit]- Frishberg, Nancy (1972). "Navajo object markers and the great chain of being". In Kimball, J. (ed.). Syntax and semantics. Vol. 1. New York: Seminar Press. pp. 259–266.

- Hale, Kenneth L. (1973). "A note on subject–object inversion in Navajo". In Kachru, B. B.; Lees, R. B.; Malkiel, Y.; Pietrangeli, A.; Saporta, S. (eds.). Issues in linguistics: Papers in honor of Henry and Renée Kahane. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 300–309.

- Hardy, Frank (1979). Navajo Aspectual Verb Stem Variation (PhD thesis). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. CA979H1979a.

- Hoijer, Harry (1945). Navaho phonology. University of New Mexico publications in anthropology. Vol. 1. University of New Mexico Press. OCLC 3339153.

- Hoijer, Harry (1945). "Classificatory verb stems in the Apachean languages". International Journal of American Linguistics. 11 (1): 13–23. doi:10.1086/463846. S2CID 144468739.

- Hoijer, Harry (1945). "The Apachean verb, part I: Verb structure and pronominal prefixes". International Journal of American Linguistics. 11 (4): 193–203. doi:10.1086/463871. S2CID 143582901.

- Hoijer, Harry (1946). "The Apachean verb, part II: The prefixes for mode and tense". International Journal of American Linguistics. 12 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1086/463881. S2CID 143035135.

- Hoijer, Harry (1946). "The Apachean verb, part III: The classifiers". International Journal of American Linguistics. 12 (2): 51–59. doi:10.1086/463889. S2CID 144657113.

- Hoijer, Harry (1948). "The Apachean verb, part IV: Major form classes". International Journal of American Linguistics. 14 (4): 247–259. doi:10.1086/464013. S2CID 144801708.

- Hoijer, Harry (1949). "The Apachean verb, part V: The theme and prefix complex". International Journal of American Linguistics. 15 (1): 12–22. doi:10.1086/464020. S2CID 143799617.

- Hoijer, Harry (1970). A Navajo lexicon. University of California Publications in Linguistics. Vol. 78. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kari, James (1975). "The disjunct boundary in the Navajo and Tanaina verb prefix complexes". International Journal of American Linguistics. 41 (4): 330–345. doi:10.1086/465374. S2CID 144924113.

- Kari, James (1976). Navajo verb prefix phonology. Garland. ISBN 0824019687.

- Reichard, Gladys A. (1951). Navaho grammar. Publications of the American Ethnological Society. Vol. 21. New York: J. J. Augustin.

- Sapir, Edward (1932). "Two Navaho puns". Language. 8 (3): 217–220. doi:10.2307/409655. JSTOR 409655.

- Sapir, Edward; Hoijer, Harry (1942). Navaho texts. William Dwight Whitney series. Linguistic Society of America.

- Sapir, Edward; Hoijer, Harry (1967). Phonology and morphology of the Navaho language. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- The Franciscan Fathers (1910). An ethnologic dictionary of the Navaho language. Saint Michaels, AZ: Franciscan Fathers.

- Wall, C. Leon; Morgan, William (1994) [1958, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Branch of Education, Bureau of Indian Affairs]. Navajo-English dictionary. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-7818-0247-4.

- Webster, Anthony K (2004). "Coyote Poems: Navajo Poetry, Intertextuality, and Language Choice". American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 28 (4): 69–91. doi:10.17953/aicr.28.4.72452hlp054w7033 (inactive 19 October 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2025 (link) - Webster, Anthony K (2006). "'ALk'idaa' Ma'ii Jooldlosh, Jini': Poetic Devices in Navajo Oral and Written Poetry". Anthropological Linguistics. 48 (3): 233–265.

- Webster, Anthony K. (2009). Explorations in Navajo Poetry and Poetics. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Witherspoon, Gary (1971). "Navajo Categories of Objects at Rest". American Anthropologist. 73: 110–127. doi:10.1525/aa.1971.73.1.02a00090.

- Witherspoon, Gary (1977). Language and Art in the Navajo Universe. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08966-8.

- Young, Robert W. (2000). The Navajo Verb System: An Overview. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-2172-0.

External links

[edit]- Hózhǫ́ Náhásdlį́į́ʼ – Language of the Holy People (Navajo web site with flash and audio, helps with learning Navajo), gomyson.com

- Navajo Swadesh vocabulary list of basic words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Contrasts between Navajo consonants (sound files from Peter Ladefoged). ucla.edu

- Navajo Language & Bilingual Links (from San Juan school district). sanjuan.k12.ut.us

- Navajo Language Academy, navajolanguageacademy.org

- Tuning in to Navajo: The Role of Radio in Native Language Maintenance, jan.ucc.nau.edu

- An Initial Exploration of the Navajo Nation's Language and Culture Initiative, jan.ucc.nau.edu

- Languagegeek Unicode fonts and Navajo keyboard layouts, languagegeek.com

- Navajo fonts, dinecollege.edu

- The Navajo Language, library.thinkquest.org

- Reflections on Navajo Poetry, ou.edu

- How to count in Navajo, languagesandnumbers.com

- Digital Public Library of America. Navajo-language items, various dates.

- iPad keyboard app[permanent dead link]

- Android keyboard app

- Android dictionary app

Linguistics

[edit]- Navajo reflections of a general theory of lexical argument structure (Ken Hale & Paul Platero), museunacional.ufrj.br

- Remarks on the syntax of the Navajo verb part I: Preliminary observations on the structure of the verb (Ken Hale), museunacional.ufrj.br

- The Navajo Prolongative and Lexical Structure (Carlota Smith), cc.utexas.edu

- A Computational Analysis of Navajo Verb Stems (David Eddington & Jordan Lachler), linguistics.byu.edu

- Grammaticization of Tense in Navajo: The Evolution of nt'éé (Chee, Ashworth, Buescher & Kubacki), linguistics.ucsb.edu

- A methodology for the investigation of speaker's knowledge of structure in Athabaskan (Joyce McDonough & Rachel Sussman), urresearch.rochester.edu

- How to use Young and Morgan's The Navajo Language (Joyce McDonough), bcs.rochester.edu

- Time in Navajo: Direct and Indirect Interpretation (Carlota S. Smith, Ellavina T. Perkins, Theodore B. Fernald), cc.utexas.edu

- OLAC Resources in and about the Navajo language

| Item | Label/en | native label | Code | distribution map | number of speakers, writers, or signers | UNESCO language status | Ethnologue language status | ?itemwiki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q36806 | Southern Quechua | qu:Urin Qichwa qu:Qhichwa qu:Qichwa |

qu |  |

6000000 | 2 vulnerable | Quechua Wikipedia | |

| Q35876 | Guarani | gn:Avañe'ẽ | gn |  |

4850000 | 1 safe | 1 National | Guarani Wikipedia |

| Q4627 | Aymara | ay:Aymar aru | ay |  |

4000000 | 2 vulnerable | Aymara Wikipedia | |

| Q13300 | Nahuatl | nah:Nawatlahtolli nah:nawatl nah:mexkatl |

nah |  |

1925620 | 2 vulnerable | Nahuatl Wikipedia | |

| Q891085 | Wayuu | guc:Wayuunaiki | guc |  |

300000 | 2 vulnerable | 5 Developing | Wayuu Wikipedia |

| Q33730 | Mapudungun | arn:Mapudungun | arn |  |

300000 | 3 definitely endangered | 6b Threatened | Mapuche Wikipedia |

| Q13310 | Navajo | nv:Diné bizaad nv:Diné |

nv |  |

169369 | 2 vulnerable | 6b Threatened | Navajo Wikipedia |

| Q25355 | Greenlandic | kl:Kalaallisut | kl |  |

56200 | 2 vulnerable | 1 National | Greenlandic Wikipedia |

| Q29921 | Inuktitut | ike-cans:ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᑦ iu:Inuktitut |

iu |  |

39770 | 2 vulnerable | Inuktitut Wikipedia | |

| Q33388 | Cherokee | chr:ᏣᎳᎩ ᎧᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ chr:ᏣᎳᎩ |

chr |  |

12300 | 4 severely endangered | 8a Moribund | Cherokee Wikipedia |

| Q33390 | Cree | cr:ᐃᔨᔨᐤ ᐊᔨᒧᐎᓐ' cr:nēhiyawēwin |

cr |  |

10875 8040 |

Cree Wikipedia | ||

| Q32979 | Choctaw | cho:Chahta anumpa cho:Chahta |

cho |  |

9200 | 2 vulnerable | 6b Threatened | Choctaw Wikipedia |

| Q56590 | Atikamekw | atj:Atikamekw Nehiromowin atj:Atikamekw |

atj |  |

6160 | 2 vulnerable | 5 Developing | Atikamekw Wikipedia |

| Q27183 | Iñupiaq | ik:Iñupiatun | ik |  |

5580 | 4 severely endangered | Inupiat Wikipedia | |

| Q523014 | Muscogee | mus:Mvskoke | mus |  |

4300 | 3 definitely endangered | 7 Shifting | Muscogee Wikipedia |

| Q33265 | Cheyenne | chy:Tsêhesenêstsestôtse | chy |  |

2400 | 3 definitely endangered | 8a Moribund | Cheyenne Wikipedia |

Navajo language

View on GrokipediaLinguistic Classification

Genealogical Affiliation

The Navajo language (Diné bizaad) is classified as a member of the Southern Athabaskan (also known as Apachean) subgroup within the Athabaskan language family, which comprises approximately 40 languages spoken across North America.[10] The Athabaskan family itself forms the core of the Na-Dené (or Na-Dene) language phylum, alongside the Eyak and Tlingit languages, with the inclusion of Haida remaining debated among linguists due to insufficient evidence of regular sound correspondences.[11] This affiliation is supported by shared lexical items, such as cognates for body parts and numerals, and systematic phonological and morphological correspondences, including verb stem structures and tone systems derived from Proto-Athabaskan consonants.[12] Within the Southern Athabaskan subgroup, Navajo is most closely related to the various Apache languages, including Western Apache, Mescalero Apache, Chiricahua Apache, and Jicarilla Apache, forming a dialect continuum characterized by mutual intelligibility among some varieties but distinct phonological innovations, such as Navajo's merger of certain proto-vowel distinctions.[13] These languages trace their divergence from Northern Athabaskan around 1,000–1,500 years ago, based on glottochronological estimates and archaeological correlations with Athabaskan migrations into the American Southwest.[14] The Southern subgroup contrasts with Northern Athabaskan (e.g., languages like Slavey and Gwich'in spoken in Alaska and Canada) and Pacific Coast Athabaskan (e.g., Hupa and Tolowa in California), primarily through geographic distribution and innovations like the development of glottalized nasals in Navajo and Apache.[10] Proposals linking Na-Dené to the Yeniseian languages of Siberia (as in the Dené-Yeniseian hypothesis) suggest a deeper Eurasian connection for Athabaskan via shared pronominal paradigms and verb morphology, but this remains a minority view without consensus, as it does not alter Navajo's established position within Athabaskan.[15] Genealogical reconstructions rely on comparative methods applied to Proto-Athabaskan forms, reconstructed in works like those of Harry Hoijer in the mid-20th century, emphasizing verb classifiers and aspectual systems as diagnostic traits.[11]Relations to Athabaskan Languages

The Navajo language belongs to the Athabaskan (also known as Dene) language family, a branch of the Na-Dené phylum spoken across western North America from Alaska and subarctic Canada to the southwestern United States. Within this family, Navajo is classified in the Southern Athabaskan subgroup, commonly termed the Apachean languages, which diverged from northern branches through migrations southward estimated between 1000 and 1500 CE based on linguistic and archaeological correlations.[16] This subgroup comprises Navajo and several closely related Apache varieties, including Western Apache, Mescalero-Chiricahua Apache, Jicarilla Apache, Lipan Apache, and Plains Apache, all concentrated in the American Southwest.[2] Navajo shares extensive lexical and grammatical similarities with other Apachean languages, such as polysynthetic verb structures incorporating subject-object agreement, classifiers, and aspectual prefixes, reflecting inheritance from Proto-Athabaskan reconstructions that posit a complex templatic verb morphology.[10] Cognates abound in core vocabulary, for instance, Navajo łééchąąʼí ("dog") corresponds to Western Apache łééchąąʼí and Jicarilla łééchąąʼí, underscoring a common ancestral lexicon.[13] Mutual intelligibility varies but is high between Navajo and Western Apache, with speakers often understanding one another despite dialectal divergences, whereas relations to more distant northern Athabaskan languages like Slavey or Gwich'in involve deeper phonological shifts, such as Navajo's innovative high tone system absent in many northern varieties.[17] These relations highlight Navajo's position as the most populous and well-documented Athabaskan language, with approximately 170,000 speakers as of recent surveys, influencing comparative studies that reveal Southern Athabaskan's innovations like glottalized nasals and reduced consonant inventories compared to northern proto-forms.[11] Linguistic evidence supports a relatively recent divergence within Apachean, post-dating the family's broader dispersal, with shared sound changes like the merger of certain proto-stops into fricatives distinguishing the southern group.[12]Dialectal Variation

The Navajo language displays regional linguistic variation, primarily phonological, with speakers across the Navajo Nation recognizing differences in pronunciation associated with geographic areas such as northern, central, and southern regions, though these do not form sharply distinct dialects and remain mutually intelligible.[2] Such variations have been underdocumented in linguistic literature despite their salience to native speakers, who note contrasts in consonant articulation and other phonetic features.[2][18] Phonological differences include variable aspiration levels on fricatives like /th/ and /kh/, where /kh/ often shortens under English influence while /th/ retains longer duration due to affrication strength, observed across speaker demographics but varying by region and age.[18] Lateral affricates exhibit shifts, such as unaspirated /t͡ɬ/ merging toward /kl/ among younger speakers and ejective /t͡ɬ’/ toward /k͡ɬ’/ across generations, reflecting phonetic pressures from bilingualism rather than fixed dialectal boundaries.[18] Tone spread rules also vary dialectally, with some speakers limiting spread to conjunct syllables featuring long vowels or coda consonants, while others extend it more freely, affecting prosodic patterns in verbs. Grammatical variation appears subtler, including inconsistent application of the animacy hierarchy in inverse voice constructions, which declines among younger speakers regardless of region, signaling broader language change. Vocabulary and discourse particles, such as nít’ę́ę́’ for temporal sequencing, show stability without significant regional divergence.[18] Overall, contemporary variation correlates more with social factors like age and English contact than with traditional geographic dialects, contributing to ongoing sound shifts in a language spoken by approximately 170,000 people as of recent estimates.[18]Phonological System

Consonant Phonemes

The Navajo language maintains a consonant inventory comprising 32 phonemes, articulated primarily at labial, alveolar, postalveolar (palato-alveolar), lateral alveolar, velar, and glottal places of articulation.[2] This system exemplifies the phonological richness of Athabaskan languages through contrasts in aspiration, glottalization (ejectives), and voicing, particularly among stops, affricates, and fricatives.[16] Some analyses propose 33 phonemes by including marginally contrastive or dialectal variants, but the core inventory aligns with 32 distinct units as documented in phonetic studies.[2] Stops and affricates feature a three-way laryngeal contrast: unaspirated (plain), aspirated, and ejective. Alveolar and velar stops include the unaspirated /t k/, aspirated /tʰ kʰ/, and ejective /tʼ kʼ/, supplemented by the glottal stop /ʔ/. Affricates parallel this pattern across alveolar (/ts tsʰ tsʼ/), postalveolar (/tʃ tʃʰ tʃʼ/), and lateral alveolar (/tɬ tɬʰ tɬʼ/) series. Fricatives encompass voiceless /s ʃ ɬ x h/ and voiced /z ʒ ɣ/, with the lateral series lacking a distinct voiced fricative phoneme (/ɬ/ contrasts with the approximant /l/). Sonorants consist of nasals /m n/, lateral approximant /l/, and glides /w j/.[19] The standard orthography, established via the 1969 Navajo Orthography Conference and refined in subsequent linguistic works, employs digraphs and apostrophes for ejectives (e.g., ts', tł') and the glottal stop (').[20] Phonetically, unaspirated stops surface as voiced [d ɡ] intervocalically due to regressive voicing assimilation, a rule applying systematically to obstruents following sonorants or in specific morphological contexts. Ejectives involve glottal closure followed by supraglottal pressure release, producing a characteristic popping quality audible in recordings of native speakers.[19]| Manner/Place | Bilabial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Lateral Alveolar | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | n | - | - | - | - |

| Stops (unaspirated/aspirated/ejective) | - | t tʰ tʼ | - | - | k kʰ kʼ | ʔ |

| Affricates (unaspirated/aspirated/ejective) | - | ts tsʰ tsʼ | tʃ tʃʰ tʃʼ | tɬ tɬʰ tɬʼ | - | - |

| Fricatives (voiceless) | - | s | ʃ | ɬ | x | h |

| Fricatives (voiced) | - | z | ʒ | - | ɣ | - |

| Approximants | w | l | j | - | - | - |

Vowel Phonemes

The Navajo vowel system consists of four phonemic qualities: high front /i/, mid front /e/, mid back /o/, and low central /ɑ/ (orthographically i, e, o, a).[21] These qualities lack a phonemic high back vowel counterpart to /i/.[21] Each quality contrasts along three independent parameters: length (short versus long), nasality (oral versus nasalized), and tone (high versus low), yielding 16 core monophthongal distinctions.[22] [21]| Quality | Oral Short (Low/High Tone) | Oral Long (Low/High Tone) | Nasal Short (Low/High Tone) | Nasal Long (Low/High Tone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /i/ | i / í | ii / íí | į / į́ | įį / į́į |

| /e/ | e / é | ee / éé | ę / ę́ | ęę / ę́ę |

| /o/ | o / ó | oo / óó | ǫ / ǫ́ | ǫǫ / ǫ́ǫ |

| /ɑ/ | a / á | aa / áá | ą / ą́ | ąą / ą́ą |

Prosodic Features

Navajo employs a lexical tone system with two primary tones—high and low—that contrast to distinguish lexical items, primarily in verb stems at the right edge of words.[25] Low tone serves as the default, while high tone is phonetically realized as a higher fundamental frequency (F0) target on each syllable, contributing to the language's "tonal density."[25] On short vowels, tones are level (high or low); on long vowels, combinations yield level high (high-high), level low (low-low), falling (high-low), or rising (low-high) contours, effectively producing four tonal realizations.[26] Tone neutralization occurs in prefixal domains (conjunct prefixes), where low tone spreads leftward, but remains contrastive in stems.[27] Vowel length is phonemic and interacts with tone: short vowels contrast in length (e.g., [bitaʔ] "with him/her" vs. [bitaːʔ] "he/she is withholding it"), while long vowels (diphthongal in duration) host contours.[25] Length cues syllable weight but does not drive metrical prominence.[25] Stress is not phonemic in Navajo; apparent prominence on final syllables (verb stems) arises from their morphological role as content-bearing units, evidenced by longer duration and wider F0 range rather than a dedicated stress accent.[25] Instrumental analyses show no consistent stress correlates like heightened intensity or predictable F0 peaks across words.[28] Intonation lacks phonemic distinctions, such as rising contours for yes/no questions or boundary tones for declaratives versus focus; utterances often exhibit level pitch tracks without pragmatic pitch modulation.[25][29] Native speaker reports and acoustic data confirm minimal intonational variation, with pragmatic functions conveyed lexically or via particles rather than prosodic overlays.[25] Utterance-level prosody may involve pitch accents aligned to prominent syllables in some Dene languages, but Navajo prioritizes tonal specification over such systems.[30]Grammatical Structure

Morphological Typology

Navajo is classified as a polysynthetic language, in which verbs function as the core syntactic units capable of incorporating subject, object, aspect, modality, and other semantic elements into highly complex word forms that often correspond to entire clauses in less synthetic languages.[31][32] This typology arises from extensive affixation, primarily prefixing, which builds layered structures around a verb stem, enabling a single word to express predicate-argument relations without independent pronouns or nouns in many contexts.[33] The morphological system emphasizes verbal complexity over nominal, with nouns typically simpler and less inflected, relying on postpositions for relational encoding rather than case marking.[5] Key features include a templatic organization of prefixes in up to 11-12 position classes, distinguishing "disjunct" (outer, more independent) and "conjunct" (inner, tightly integrated) zones, which allows for precise encoding of tense, person, number, and classifiers that shape stem alternations.[27] While exhibiting agglutinative traits through sequential morpheme attachment, Navajo morphology incorporates fusional elements, such as stem-initial consonant mutations triggered by classifiers and aspectual modes, rendering morpheme boundaries less transparent than in purely agglutinative systems.[32] This results in verbs that can span 10 or more morphemes, as documented in analyses of paradigms from speakers in the 1980s, reflecting a degree of synthesis that supports the polysynthetic label over simpler synthetic categories.[31]Verb Morphology and Complexity

Navajo verbs exhibit polysynthetic morphology, where a single verb word can incorporate numerous affixes to encode arguments, aspect, mode, and semantic nuances, often rendering independent nouns or postpositions unnecessary. The core structure comprises a verb stem—a monosyllabic root providing the lexical base—preceded by a series of prefixes arrayed in 14 to 16 fixed position classes, along with a classifier immediately before the stem.[34][35] This templatic arrangement, detailed in standard grammars, organizes morphemes from left (disjunct domain, including iterative and adverbial elements) to right (conjunct domain, with pronominal and aspectual prefixes), culminating in the stem, enabling the verb to function as a complete clause.[36][37] The complexity arises primarily from the interplay of these position classes, which enforce strict ordering and trigger phonological interactions such as vowel harmony, nasalization, and hiatus resolution between adjacent morphemes. For instance, subject pronouns occupy positions 1–3 (singular/plural/distributive distinctions), direct object markers positions 4–5, and postpositional object pronouns further leftward, while thematic prefixes (indicating manner or direction) and deictics (proximity/distality) fill intermediary slots.[38][34] Classifiers in position 8—Ø (neutral or active intransitive), D- (areal or handled objects), L- (cylindrical or animate), and Yi- (multipurpose or solid roundish)—not only mark transitivity but also condition stem allomorphy and semantic categories like shape or animacy in "classificatory verbs," where the stem varies based on the object's properties (e.g., handling a rope vs. a flat flexible object).[36][39] This system yields thousands of verb forms from a limited set of stems (around 600–700 base stems), amplifying expressive density but imposing acquisition challenges, as evidenced by child speech studies showing gradual mastery of prefix sequencing.[40][35] Aspect and mode further elaborate this framework, with Navajo distinguishing up to 12 modes (e.g., imperfective for ongoing/habitual actions, perfective for completed telic events, progressive for continuous states, and future for prospective), each subdivided into stem sets (e.g., three imperfectives: inceptive, continuative, customary).[33][34] Prefixes in positions 9–11 mark aspectual distinctions, such as inceptive -yi- or semelfactive, interacting with classifiers to enforce paradigmatic regularity; irregularities, like suppletive stems in certain aspects, reflect historical Athabaskan retentions rather than productive rules.[36] Linguists characterize this as typologically rare for its rigid prefix templaticity combined with semantic intricacy, contrasting with suffix-heavy systems and contributing to Navajo's reputation for morphological elaboration in Athabaskan languages.[27][40] Such features underpin the language's efficiency in discourse, where a verb like yinishéí ("I am carrying it around by its handle") fuses subject, object classifier, motion, and aspect into one form, though they also correlate with observed erosion in heritage speakers amid language shift.[41][40]Noun Morphology and Possession

Navajo nouns display minimal inflectional morphology, lacking obligatory marking for case, gender, or definiteness. Number is not systematically encoded on noun stems; plurality is conveyed contextually through accompanying verbs, quantifiers, or, in rare instances, suffixes such as -í on certain human nouns (e.g., hastiin 'man' optionally becomes hastiinoí 'men'). [42] Noun derivation primarily involves compounding or nominalization from verbs, but stems remain largely underived. [34] Possession in Navajo is predominantly alienable and realized via pronominal prefixes affixed directly to the noun stem, distinguishing it from the more complex verbal possession strategies. [42] These prefixes indicate the person and number of the possessor, with the possessed noun following immediately after an optional possessor noun phrase if specified (e.g., hastiin bich'ah 'man's hat', where bi- marks third-person possession). [5] Inalienable possession, typically involving body parts or kinship terms, employs the same prefix system but may trigger phonological adjustments like high tone on the prefix or stem-initial nasalization in some cases, reflecting historical Athabaskan patterns. [43] Body part nouns often appear possessed in discourse but are not grammatically obligatory, unlike in some Northern Athabaskan languages. [44] The core possessive prefix paradigm for nouns is as follows:| Person/Number | Singular Prefix | Plural/Dual Prefix |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | shi- | danihi- |

| 2nd | ni- | danihí- |

| 3rd (definite) | bi- | bąąh- |

| 3rd (indefinite) | ha- | - |

Syntactic Patterns

Navajo syntax features verb-final clauses, with a primary Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) word order that allows flexibility for discourse prominence, such as Object-Subject-Verb (OSV) variants, due to extensive verbal agreement marking subject and object person and number via prefixes.[45][47][13] This morphological encoding enables pro-drop of core arguments, as the verb stem incorporates classifiers and thematic prefixes to specify transitivity and aktionsart.[32] Third-person distinctions rely on prefixes like yi- (obviative or distant) and bi- (proximate), which resolve ambiguities in multi-argument contexts without strict reliance on linear order.[37] Postpositional phrases modify nouns and follow them, functioning analogously to prepositions in Indo-European languages but inflecting for the possessor or object via pronominal prefixes identical in form to those on verbs.[48][39] For instance, a postposition like -kɛh ('beside') combines with a prefix such as shí- (first-person singular) to yield shíkɛh ('beside me'), attaching directly to the head noun without intervening determiners, as Navajo lacks articles.[48] Relative clauses are typically headless or internally headed, formed by suffixing relativizers like -íí or -ígíí to the verb, without dedicated relative pronouns or external heads; the clause integrates into the matrix via nominalization, permitting extraposition for focus.[49][50][51] Yes/no questions arise through initial particles like da' or rising intonation, while content questions employ interrogative particles (ha'át'íí 'what', *hane' 'where') often in situ, with syntactic movement optional based on scope.[52][53] Negation employs the discontinuous circumfix doo ... da enveloping the verb, altering mode and aspect paradigms, as in doo yisháá da ('he/she does not carry it'), with alternatives like t'áadoo for emphatic or modal negation.[5] Coordination links clauses via juxtaposition or particles, maintaining verb-final alignment without conjunctions equivalent to English 'and'.[54]Lexical Features

Core Semantic Domains

The Navajo lexicon emphasizes domains tied to social structure, environment, and spatial cognition, reflecting the language's Athabaskan roots and cultural context. Kinship terms form a foundational semantic domain, organized around a matrilineal clan system with over 100 clans grouped into phratries, where membership is inherited maternally and dictates social relations, marriage prohibitions, and identity. Basic relational terms distinguish maternal and paternal lines: shimá for mother, shizhéʼé for father, shícheii for maternal grandfather, and shínaaí for older brother, with possessive prefixes like shí- ("my") integrating them into utterances.[55][56] The concept of k'é encompasses broader affective solidarity beyond blood ties, extending to compassion and mutual aid within the community.[55]| Kinship Term | Navajo Word | English Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Mother | shimá | mother |

| Father | shizhéʼé | father |

| Maternal grandfather | shícheii | maternal grandfather |

| Paternal grandmother | shínálí | paternal grandmother |

| Older sister | shídeezhí | older sister (speaker's perspective) |

Loanwords from Contact Languages