Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Notoryctidae

View on Wikipedia

| Notoryctidae Temporal range: Oligocene - Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Notoryctes typhlops | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Clade: | Agreodontia |

| Order: | Notoryctemorphia Kirsch in Hunsaker, 1977 |

| Family: | Notoryctidae Ogilby, 1892 |

| Genera | |

| |

Notoryctidae (/noʊtəˈrɪktɪdiː/; from Ancient Greek νότος (nótos), meaning "south", and ὀρυκτήρ (oruktḗs), meaning "digger") are a family of marsupials comprising the marsupial moles and their fossil relatives. It is the only family in the order Notoryctemorphia.

Taxonomy

[edit]A fossil species in a new genus was published as Naraboryctes. A new diagnosis for Notoryctidae was also provided in the species first description, as a consequence of the discovery of a fossil species in the family.[1]

Description

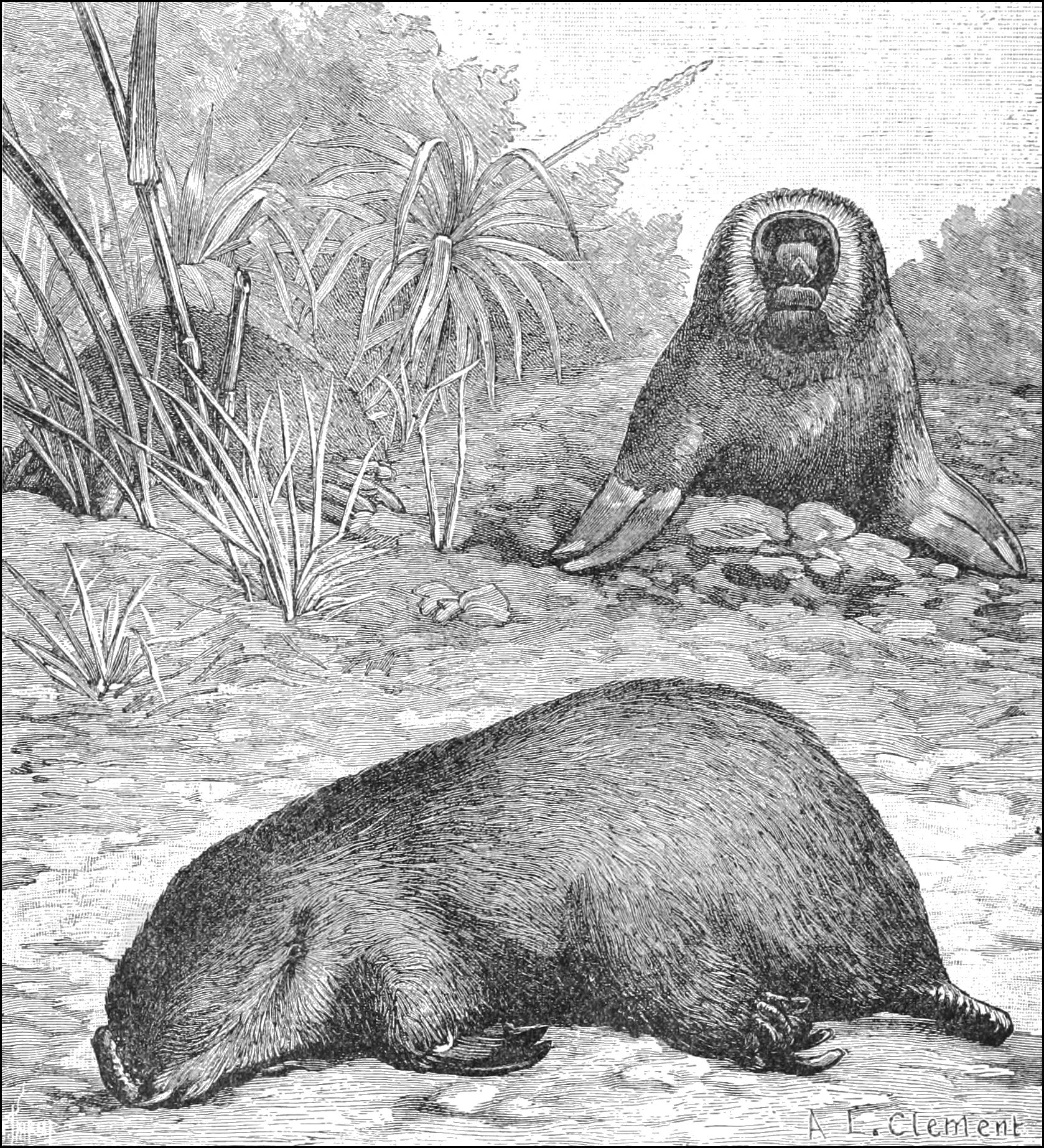

[edit]The group appear to have diverged from other marsupials at an early stage and are highly specialised to foraging through loose sand; the unusual features have seen the unique family placed in the taxonomic order Notoryctemorphia Aplin & Archer, 1987. The eyes and external ears are absent in the modern species, the nose is shielded and mouth reduced in size, and they use pairs of well developed claws to move beneath the sand.[1] The Australian animals resemble species known as moles, burrow building mammals found in other continents, and were collectively referred to as 'marsupial moles'. The regional names for the well known animals, established before their published descriptions, are used to refer to the species.[citation needed]

The extant notoryctid species are subterranean, and are extremely well adapted to moving through sand plains and dunes, these are the two species of genus Notoryctes Stirling, 1891.[1] The animals are known as itjaritjari (for the species N. typhlops) and kakarratul (for the species N. caurinus).[1]

The dental formula is I1-5/1-3, C1/1, P1-3/1-3, M1-4/1-4.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Archer, M. (2011-05-22). "Australia's first fossil marsupial mole (Notoryctemorphia) resolves controversies about their evolution and palaeoenvironmental origins". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1711): 1498–1506. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1943. PMC 3081751. PMID 21047857.

Notoryctidae

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and phylogeny

Classification

Notoryctidae is a family of marsupials classified within the kingdom Animalia, phylum Chordata, class Mammalia, infraclass Marsupialia, order Notoryctemorphia, with the genus Notoryctes comprising the sole extant representatives. The genus Notoryctes, derived from the Greek words "notos" (south) and "oryktes" (digger), reflects the southern Australian distribution and fossorial lifestyle of its members.[11] Two extant species are recognized: Notoryctes typhlops (southern marsupial mole), described by E. C. Stirling in 1889 from specimens collected in central Australia, and Notoryctes caurinus (northern marsupial mole), described by O. Thomas in 1920 from material found near Wallal, Western Australia. Phylogenetically, Notoryctemorphia, including Notoryctidae, is positioned as sister to Peramelemorphia (bandicoots and bilbies) within the Agreodontia clade of the marsupial superorder Australidelphia, with their common ancestor dating to about 60 million years ago; this relationship is supported by whole-genome sequencing and earlier molecular and craniodental studies.[10][12][13] Fossil relatives include the Miocene genus Naraboryctes, represented by Naraboryctes philcreaseri from early Miocene deposits in Riversleigh, Queensland, which is considered a basal notoryctid exhibiting transitional dental features toward the zalambdodont condition of modern species.[6]Evolutionary history

The family Notoryctidae emerged during the early Miocene, approximately 23 to 16 million years ago, with the earliest known fossils discovered in the Riversleigh World Heritage Area of northwestern Queensland, Australia.[6] These deposits reveal a wet forest paleoenvironment that predated the widespread aridification of the Australian continent, suggesting that notoryctids initially evolved in mesic habitats before adapting to increasingly xeric conditions in the later Neogene.[6] The fossil record of Notoryctidae is sparse but informative, highlighting transitional forms with primitive burrowing adaptations. Key specimens include Naraboryctes philcreaseri, an early Miocene species from Riversleigh that exhibits incipient fossorial traits such as a hypertrophied olecranon process on the ulna and zalambdodont dentition achieved through paracone suppression, indicating an early stage in the acquisition of specialized underground locomotion.[6] Other early Miocene zalambdodont marsupials, such as Yalkaparidon species from Riversleigh, display similar dental adaptations like reduced molars suited for insectivory, indicating convergent evolution of such traits following Gondwanan isolation around 35 million years ago.[14][6] Notoryctids exemplify convergent evolution with golden moles of the family Chrysochloridae, independently developing fossorial specializations including reduced eyes, enlarged forelimbs for digging, and streamlined bodies in response to Australia's Miocene aridification, which transformed vast rainforests into desert landscapes.[6] Recent phylogenetic analyses, bolstered by whole-genome sequencing of Notoryctes typhlops in 2025, confirm a deep divergence within Marsupialia, positioning Notoryctidae as sister to Peramelemorphia (bandicoots and bilbies) within the Agreodontia clade, with their common ancestor dating to about 60 million years ago.[10]Physical characteristics

Morphology

Members of the Notoryctidae family, known as marsupial moles, exhibit a highly specialized tubular body shape adapted for fossorial life, with head-body lengths ranging from 12 to 16 cm and weights between 30 and 70 g.[2] This compact, cylindrical form lacks a distinct neck, facilitating efficient movement through sandy substrates.[15] The fur of Notoryctidae is dense, silky, and iridescent, ranging in color from cream to golden-yellow, often with regional variations influenced by soil staining.[1][11] The short, fine hairs lie flat against the body in any direction, reducing friction during bidirectional burrowing.[2] The head is cone-shaped with a leathery, heavily keratinized snout that forms a protective shield, while the forelimbs are powerful and equipped with enlarged, spade-like claws on the third and fourth digits for excavating soil; the hindlimbs are notably reduced.[11][3] Reproductive structures include a backward-opening pouch in females, containing two teats for nursing young, and prepenial testes in males that remain internal rather than descending into a scrotum.[11][2] Between species, the southern marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops) measures 12–16 cm in head-body length with a reddish tint to its fur from soil staining, whereas the northern marsupial mole (Notoryctes caurinus) measures 12–16 cm in head-body length (slightly more slender) and displays a pinkish-yellow hue.[15][3] These external features underscore their convergence with eutherian moles in form, though they are unrelated marsupials.[1]Sensory and physiological adaptations

Members of the Notoryctidae family exhibit profound sensory modifications suited to their subterranean existence, where vision is rendered obsolete by perpetual darkness. Their eyes are vestigial, lacking external openings and covered by a thick layer of fur, with no discernible optic nerve, eye muscles, lens, or photoreceptor cells such as rods and cones.[11] This regression is part of a broader convergent evolution in subterranean mammals, involving loss-of-function mutations in ocular genes and enhancers, which accelerate adaptations to non-visual environments.[16] Hearing in notoryctids compensates for the absence of vision, with no external ear pinnae but conspicuously inflated auditory bullae that enhance sensitivity to low-frequency sounds, potentially aiding in detecting vibrations from prey or conspecifics through soil.[11] Tactile sensitivity is facilitated by specialized sensory cells in the skin, including clusters resembling taste buds in areas like the ischiotergal patch, which may detect mechanical vibrations or chemical cues in the substrate; notably, vibrissae (whiskers) are absent.[11] Olfaction is highly developed, supported by enormously enlarged olfactory bulbs and a well-developed Jacobson's organ, enabling the detection of prey scents within dark tunnels via expanded nasal cavities.[11] Physiologically, notoryctids maintain a low basal metabolic rate, approximately 0.63 mL O₂ g⁻¹ h⁻¹ at 30°C ambient temperature, representing about 50% of the expected mammalian standard, which supports sporadic activity in resource-scarce burrow environments. This is coupled with tolerance for low-oxygen conditions, facilitated by an extra haemoglobin gene that enhances oxygen transport in the oxygen-poor air of deep sand burrows.[17] Their unique ability to "swim" through loose sand incurs a net cost of transport of 0.124 mL O₂ g⁻¹ m⁻¹, reflecting efficient energy use during fossorial locomotion. Waste management is streamlined by a true cloaca—a single orifice for digestive, urinary, and reproductive functions—unique among marsupials and featuring a highly glandular lining for efficient elimination in confined spaces.[11] Thermoregulation is relaxed and labile, with body temperatures ranging from 22.7°C to 30.8°C across ambient temperatures of 15–30°C, lower than typical for small marsupials and indicating poor endothermic control suited to stable subsurface conditions. Their pale, cream-colored fur, resulting from loss-of-function mutations in genes like ASIP and MC1R, likely aids in reflecting heat during rare surface exposures in hot deserts, while behavioral estivation during extreme heat conserves energy.[18] This vulnerability to hypothermia is evident in captive individuals, underscoring adaptations optimized for arid, fossorial life rather than broad thermal variability.[11]Distribution and habitat

Geographic range

Notoryctidae, the family comprising the marsupial moles, is endemic to the arid interior of Australia, primarily occupying south-central and north-central regions across sandy desert landscapes.[11] The two extant species exhibit distinct but partially overlapping distributions, with records concentrated in areas of aeolian sand dunes and plains.[19] Overall, the family's range spans Western Australia, the Northern Territory, and South Australia, but no confirmed occurrences exist in Queensland or eastern regions.[20] The southern marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops) occupies the borders of South Australia, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory, ranging from the Great Victoria Desert in the south to the Tanami Desert in the north.[19] Specific records include the western Simpson Desert, Finke River area, and north-eastern South Australia near the Great Australian Bight.[11] This species' distribution is documented through 679 occurrence records, primarily from scattered sightings and museum specimens.[19] The northern marsupial mole (Notoryctes caurinus) is restricted to north-western Western Australia, with its range encompassing the Great Sandy Desert, Little Sandy Desert, and northern Gibson Desert, and possible extension into the western Tanami Desert of the Northern Territory.[21] Key historical records originate from sites such as Sturt Creek, Warburton Range, 80-Mile Beach, and Wallal Downs.[11] Approximately 34 occurrence records support this distribution, based on limited specimens and Indigenous knowledge.[21] No major range contraction has been documented for either species since their descriptions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, though sparse records reflect their cryptic, subterranean lifestyle.[20] Recent data from the Atlas of Living Australia (accessed June 2024) indicate ongoing presence across these regions, with post-2020 surveys by Indigenous rangers confirming occurrences in spinifex-dominated desert areas, including a 2024 sighting of N. caurinus in the Great Sandy Desert.[10][22]Habitat preferences

Notoryctidae, the family encompassing the marsupial moles, exhibit a strong preference for loose, aeolian sands characteristic of desert dunes and plains across central and western Australia. These species, including Notoryctes typhlops and N. caurinus, are adapted to tunneling through soft, friable substrates that allow efficient burrowing, typically at depths ranging from 20 cm to 2.5 m. They avoid compacted clays, loamy soils, or hard-packed sands, which impede their fossorial locomotion and are unable to traverse such barriers effectively.[4][11][2] Vegetation in preferred habitats often consists of hummock grasses such as spinifex (Triodia spp. and Plectrachne spp.), which provide sparse cover and support populations of subterranean insects that serve as prey. These grasses dominate sand ridges and inter-dunal areas, with associated shrubs like acacias (Acacia spp.) and occasional mallee eucalypts (Eucalyptus gamophylla) in well-vegetated dunes. Surface activity increases in softened soils following rainfall, when ephemeral annual grasses and forbs emerge, potentially enhancing foraging opportunities near the surface.[11][4][23] The climatic regime favored by Notoryctidae is that of arid and semiarid deserts, featuring hot summers with temperatures frequently exceeding 40°C and mild winters occasionally marked by frosts. Annual rainfall is low and erratic, averaging around 300 mm, concentrated in irregular events that trigger surfacing and tunneling in recently moistened sands. Such conditions prevail in regions like the Great Victoria and Simpson-Strzelecki dunefields, where the combination of extreme aridity and sandy substrates defines the ecological niche.[23][4] Microhabitats are primarily confined to inter-dunal flats, sand ridges, and dune crests or slopes, with higher activity observed on mid- to old-aged fire-succession sites supporting mature spinifex. Notoryctidae construct no permanent burrows; instead, they form temporary tunnels that collapse behind them as they move, leaving backfilled traces most evident on dune slopes and crests rather than in swales or harder basal sands. Sandy river flats adjacent to dunes may also be utilized sporadically.[23][4][11]Behavior and ecology

Burrowing and locomotion

Members of the Notoryctidae family, comprising the southern marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops) and northern marsupial mole (Notoryctes caurinus), are highly specialized for fossorial life through a distinctive "sand-swimming" burrowing method. They propel themselves forward by using enlarged forelimbs with spade-like claws to scoop and displace loose sand postero-medially underneath the body in a parasagittal digging motion, while powerful hind limbs provide thrusting force and the tail acts as a fifth limb for stability during pentapedal locomotion.[11] This technique allows them to move through sand as if it were a fluid medium, creating temporary tunnels at depths ranging from 10 cm to 2.5 m that collapse immediately behind them due to backfilling, resulting in no permanent burrow systems.[3] The energetic efficiency of this underground sand-swimming far exceeds surface travel, enabling navigation through soft, arid substrates like sand dunes and plains.[3] Surface emergences are infrequent and brief, occurring primarily after heavy rainfall or during windy periods when the sand is moist and easier to traverse, though tracks can occasionally appear in dry conditions.[2] Above ground, locomotion is awkward and inefficient, involving a sinuous, shuffling gait where the forelimbs drag the body forward and hind limbs shove from behind, producing distinctive trails of three parallel furrows from the limbs and tail; individuals cover only a few meters before rapidly re-burrowing to evade predators.[11] This clumsy terrestrial movement underscores their adaptation to subterranean existence, with limited endurance on the surface. Notoryctids exhibit solitary activity patterns, with no observed territorial marking or social interactions, and engage in crepuscular or nocturnal bursts of intense burrowing followed by extended dormancy to manage energy demands in harsh desert environments.[11][3] Both species avoid permanent nests, relying instead on transient tunnels, though N. caurinus demonstrates greater agility in deeper, looser sands of dune systems compared to N. typhlops, which prefers shallower sand plains.[25][2]Diet and foraging

Notoryctidae species are primarily insectivorous, feeding on a variety of subterranean invertebrates encountered during burrowing. The diet of Notoryctes typhlops consists mainly of social insects such as ants (including species from genera Iridomyrmex and subfamilies Myrmeciinae and Rhytidoponera) and termites, along with beetle larvae and pupae (Coleoptera), as determined from gut contents of preserved specimens.[26][2] Other prey items include larvae and pupae of Lepidoptera, Orthoptera, and Hymenoptera, as well as occasional scorpions, spiders, centipedes, and small geckos; seeds and plant material appear incidentally, likely from ant nests.[26][4] Foraging occurs entirely underground, with individuals "swimming" through sand to follow insect galleries and detect prey using olfactory cues and sensitivity to vibrations or sand shifts via the inner ear.[11][3] Prey is manipulated and consumed on-site using shovel-like foreclaws to pin or squeeze small items like larvae, while larger specimens are chewed progressively with premolars; ants and termites are often ingested incidentally during consumption of eggs or brood.[2] Notoryctids exhibit opportunistic feeding, surfacing rarely after heavy rain when surface insects may become more accessible, though most activity remains subterranean at depths of 10 cm to 2.5 m.[27][3] Unlike some fossorial rodents, Notoryctidae lack specialized cheek pouches for food storage, relying instead on immediate consumption during foraging excursions. The digestive tract is relatively short (approximately 29 mm from pylorus to cloaca in N. typhlops), suited to processing soft-bodied invertebrates without extensive fermentation.[11] Dietary preferences vary slightly between species, with N. typhlops showing a stronger focus on ants and their brood alongside termites and beetle larvae, based on prey selection indices indicating proportional intake or preference for these items relative to availability.[26] In contrast, N. caurinus incorporates more diverse items, including beetle larvae and pupae, ant eggs, centipedes, small lizards, eggs, seeds, and vegetable matter, reflecting potentially broader opportunistic habits in its northern range.[3] Both species are classified as dietary generalists despite their specialized subterranean lifestyle.[28]Reproduction and life cycle

The reproduction of Notoryctidae, comprising the southern marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops) and northern marsupial mole (Notoryctes caurinus), remains poorly understood due to the family's cryptic, fossorial lifestyle, with most knowledge derived from preserved specimens. Breeding appears seasonal, occurring around November in spring, as indicated by the discovery of pregnant females during this period.[2][3] The mating system is unknown, with no observations of copulation or pair bonding, though females are the sole providers of parental care, offering provisioning and protection to altricial young without male involvement post-mating.[11][3] Females possess a backward-facing pouch containing two teats, suggesting a maximum litter size of one to two young per birth. Newborns are born in an underdeveloped state typical of marsupials and crawl unaided into the pouch shortly after birth, where they attach to the teats for nursing.[3][11] The gestation period is unknown but presumed short, aligning with the 10–38 day range observed in other marsupials. Details on pouch life duration and weaning are lacking, though pouch young have been documented with developing features such as pigmented eye patches, visible ear openings, and enlarged forelimb digits at approximately 10 mm crown-rump length.[11] Sexual maturity and lifespan are also not well established. Age at maturity remains undocumented, though general marsupial patterns suggest it occurs within the first year. In the wild, lifespan is estimated at around 1.5 years, limited primarily by predation; in captivity, individuals survive less than two years, often succumbing to conditions like hypothermia or pneumonia.[3][2] No extended post-weaning parental care has been observed.[11]Conservation

Status and threats

Both species of Notoryctidae, Notoryctes typhlops (southern marsupial mole) and N. caurinus (northern marsupial mole), are classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List (as of 2024) owing to potentially stable, widespread populations, though data limitations on trends, distribution, and ecology persist. Under Australian federal legislation (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999), both are listed as Endangered, reflecting concerns over their restricted ranges and vulnerability to environmental pressures despite limited quantitative evidence of decline.[29][4] Population sizes are difficult to estimate due to the species' cryptic, fossorial lifestyle; fewer than 100 individuals of each have been captured or observed since their discovery in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, respectively, and museum records indicate sporadic detections at rates of 5–15 per decade.[3][4] The IUCN estimates 10,000–50,000 mature individuals for N. caurinus (as of 2024), while the population of N. typhlops remains unquantified.[30] No clear evidence of population decline exists, but their elusive nature—spending most of their lives underground—precludes effective monitoring, leading experts to infer potential stability only through indirect signs like burrow traces.[29] A 2025 genomic study of N. typhlops indicated low genetic diversity and a population bottleneck predating human arrival, highlighting historical vulnerabilities.[10] Primary threats include predation by introduced predators such as foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and feral cats (Felis catus), which opportunistically target moles when they surface after rains; fox scats in arid regions contain mole remains in up to 10% of samples.[4] Habitat disruption arises from mining activities, cattle and camel grazing that compacts soil and alters vegetation, and modified fire regimes that reduce prey availability by changing dune structures.[29] Climate change exacerbates risks by shifting rainfall patterns, potentially drying sandy habitats and limiting insect prey.[4] For N. typhlops, southern populations face heightened vulnerability from infrastructure development, including roads, pipelines, and mining in the more accessible central Australian ranges.[25] In contrast, N. caurinus appears potentially more stable in its northwestern desert strongholds but is threatened by ongoing desert expansion driven by aridification and habitat fragmentation.[29]Protection and research

Both species of Notoryctidae, the southern marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops) and the northern marsupial mole (N. caurinus), are protected under Australia's Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), where they are listed as Endangered due to their restricted distributions and vulnerability to habitat degradation.[4] National recovery plans for both species have been in place since 2005, outlining actions to address threats and improve conservation status, with the initial plan covering 2005–2010 and subsequent updates focusing on monitoring and threat mitigation.[31] These protections also extend to state-level legislation, such as Endangered status under South Australia's National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 and Vulnerable status under the Northern Territory's Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 2000.[4] Conservation efforts emphasize habitat monitoring across arid desert regions, including systematic surveys in areas like the Anangu Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara Lands in South Australia and the Tanami Desert in the Northern Territory.[4] Predator control programs target introduced species such as foxes and cats through fenced exclosures at sites including Watarrka National Park and Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, where biennial monitoring of mole tunnels assesses the impact of these interventions on local populations.[4] Captive breeding has proven not viable owing to the species' highly fossorial lifestyle and specialized physiological needs, with no individuals surviving more than a few months in captivity despite attempts.[32] Recent research advances include the 2025 genome sequencing of N. typhlops, which assembled a 3.85 Gb reference genome from a museum specimen and revealed low genetic diversity indicative of a recent population bottleneck, alongside adaptations for subterranean life such as mutations in genes related to oxygen transport and testicular descent.[10] Population surveys rely on non-invasive methods like sand-tracking of surface signs and burrow mapping, which have proven effective for estimating distribution and abundance in sandy habitats without disturbing the animals.[33] Studies at the University of Western Australia have examined burrow ecology through analyses of appendicular musculoskeletal adaptations, highlighting how forelimb specializations enable efficient swimming through sand and informing habitat suitability assessments.[34] Future conservation priorities include developing advanced non-invasive monitoring techniques, such as refined genetic sampling from scats and environmental DNA, to better track elusive populations amid ongoing threats like predation.[4] Climate modeling is also essential to predict habitat shifts in arid zones, where rising temperatures and altered rainfall patterns could exacerbate fragmentation of suitable sandy substrates for these specialized burrowers.[35]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/257938637_Functional_morphology_of_marsupial_moles_Marsupialia_Notoryctidae