Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Osborne effect

View on Wikipedia

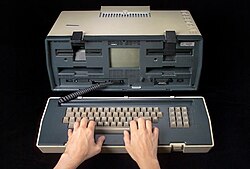

The Osborne effect is a social phenomenon of customers canceling or deferring orders for the current, soon-to-be-obsolete product as an unexpected drawback of a company's announcing a future product prematurely. It is an example of cannibalization. The term alludes to the Osborne Computer Corporation, whose second product did not become available until more than a year after it was announced. The company's subsequent bankruptcy was widely blamed on reduced sales after the announcement.[1][2]

Description

[edit]

The Osborne effect occurs when premature discussion of future, unavailable products damages sales of existing products. The name comes from the planned replacement of the Osborne 1, an early personal computer first sold by the Osborne Computer Corporation in 1981. In 1983, founder Adam Osborne pre-announced several next-generation computer models (the Osborne Executive and Osborne Vixen), which were only prototypes, highlighting the fact that they would outperform the existing model as the prototypes dramatically cut down assembly time.[3] A widely held belief was that sales of the Osborne 1 fell sharply as customers anticipated those more advanced systems, leading to a sales decline from which Osborne Computer was unable to recover. This belief appeared in the media almost immediately after the company's September 1983 bankruptcy:[4]

To give the jazzy $2,495 Osborne Executive a running start, Adam began orchestrating publicity early in 1983. We, along with many other magazines, were shown the machine in locked hotel rooms. We were required not to have anything in print about it until the planned release date in mid-April. As far as we know, nothing did appear in print, but dealers heard about the plans and cancelled orders for the Osborne 1 in droves. In early April, Osborne told dealers he would be showing them the machine on a one-week tour the week of 17 April, and emphasized that the new machine was not a competitor for the Osborne 1. But dealers didn't react the way Osborne expected; said Osborne, "All of them just cancelled their orders for the Osborne 1."

Osborne reacted by drastically cutting prices on the Osborne 1 in an effort to stimulate cash flow. But nothing seemed to work, and for several months sales were practically non-existent.[4]

Pre-announcement is done for several reasons: to reassure current customers that there is improvement or lower cost coming, to increase the interest of the media and investors in the company's future prospects, and to intimidate or confuse competitors. When done correctly, the sales or cash flow impact to the company is minimal, with the revenue drop for the current product being offset by orders or completed sales of the new product as it becomes available. However, when the Osborne effect occurs, the quantity of unsold goods increases and the company must react by discounting and/or lowering production of the current product, both of which depress cash flow.

Criticism

[edit]Interviews with former employees cast doubt on the idea that Osborne's downfall was caused solely by announcement ahead of availability.[5][6]

After renewed discussion of the Osborne effect in 2005, columnist Robert X. Cringely interviewed ex-Osborne employee Mike McCarthy, and clarified the story behind the Osborne effect. Purportedly, while the new Executive model from Osborne Computer was priced at US$2,195 and came with a 7-inch (178 mm) screen, competitor Kaypro was selling a computer with a 9-inch (229 mm) screen for $400 less, and the Kaypro machine had already begun to cut into sales of the Osborne 1, a computer with a 5-inch (127 mm) screen for $1,995.

Consequently, after inventory of the Osborne 1 had been cleared out, McCarthy believed, customers switched to Kaypro, causing monthly sales of the Executive to fall to less than 10% of its predecessor.

On 20 June 2005, The Register quoted Osborne's memoirs and interviewed Osborne repairman Charles Eicher to tell a tale of corporate decisions that contributed to the company's demise.[6] Apparently, while sales of the new model were relatively slow, they were starting to show a profit when a vice president discovered that there was an inventory of fully equipped motherboards for the older models worth $150,000. Rather than discard the motherboards, the vice president sold Osborne leadership on the idea of building them into complete units and selling them.

Soon, $2 million was spent to turn the motherboards into completed units, and for CRTs, RAM, floppy disk drives, to restore production and fabricate the molded cases. This was far more money than anybody anticipated, and also more than the company could afford at that time. In his autobiography, Osborne described this as a case of "throwing good money after bad".[6] It was at this time that the company folded.

Other examples

[edit]In 1978, North Star Computers announced a new version of its floppy disk controller with double the capacity which was to be sold at the same price as their existing range. Sales of the existing products plummeted. The company almost went bankrupt, folding in 1984.[7]

Other consumer electronic products have been continually plagued by the Osborne effect as well. In the early 1990s, TV sets' sales were depressed by talk of the imminent release of HDTV, which did not actually become widespread for another 15 years.[citation needed]

When Sega began publicly discussing their next-generation system (eventually released as the Dreamcast), barely two years after launching the Saturn, it became a self-defeating prophecy. At the time Sega had a history of short-lived consoles, particularly the Sega Mega-CD and 32X add-ons, which were considered ill-conceived "stopgaps". Those console add-ons, along with the early release of the Saturn in spring 1995 in the United States to compete with Sony's PlayStation, ended sales of Sega's own popular and successful Genesis which frustrated players (the early release meant they could not afford the console) and developers (the early release of the Saturn forced developers to rush to finish their games) alike. These factors quickly led to the failure of the Saturn: following the 1997 Dreamcast announcement, sales of Saturn consoles and software substantially tapered off in the second half of 1997, while many planned games were canceled, shortening the console's life expectancy substantially. While this let Sega focus on bringing out its successor, the premature demise of the Saturn in 1998 caused customers and developers to be skeptical and hold out, which led to the Dreamcast's failure as well, and Sega's exit from the console industry in March 2001.[8]

Another example of the Osborne effect took place as a result of Nokia's CEO Stephen Elop's implementation of the plan to shift away from Symbian to Windows Phone for its mobile software platform. On top of this, criticism of existing products was compared to the Ratner effect. Although it was known for some time that Nokia's Symbian phones were no longer competitive against Apple's iOS and Google's Android, they still generated significant profit thanks to Nokia's brand recognition until Elop's "burning platform" memo "effectively transformed the Symbian cash-cow into a dead duck". At the same time, Nokia's first Windows Phone devices would not be ready for a year, and once they were released their sales were not enough to replace the volume and profit of Symbian devices.[9] Furthermore, the announcement that Windows Phone 7 devices would not be able to upgrade to Windows Phone 8 hurt sales of Nokia's Windows Phone 7 phones, plus it was a risky move for Microsoft which "can ill afford to alienate people when there are scores of highly capable and affordable Android phones up for grabs, or years-old Apple iPhones which aren't being prematurely shut out of the iOS playground."[10][11] Poor performance led Nokia to sell its mobile phone division to Microsoft in 2013.[12]

MakerBot also appears to have fallen victim to the Osborne effect, as talking openly about a future product significantly reduced the sales of their current product.[13]

See also

[edit]- Deflation – Decrease in the general price level

- Second-system effect – Project management and software design pitfall in second major iterations

- Self-competition – Economic competition within a company

- Self-defeating prophecy – Prediction that prevents what it predicts from happening

- Trickle-down fashion – Model of product adoption in marketing

References

[edit]- ^ Osborne, Adam; Dvorak, John C. (1984). Hypergrowth: the rise and fall of Osborne Computer Corporation. Idthekkethan. ISBN 0-918347-00-9.

- ^ Grindley, Peter (1985). Standards, strategy and policy: cases and stories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-828807-7.

- ^ "StudioRed Founder on Product Design". 21 May 2018.

- ^ a b Ahl, David H. (March 1984). "Osborne Computer Corporation". Creative Computing. Ziff-Davis. p. 24. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ Cringely, Robert X. (16 June 2005). "The Osborne Effect". The Osborne Effect: Sometimes What Everyone Remembers Is Wrong. PBS. Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ a b c Andrew Orlowski (20 June 2005). "Taking Osborne out of the Osborne Effect". The Register. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ^ Andrew Orlowski, "Taking Osborne out of the Osborne Effect", The Register, 20 June 2005

- ^ Jason Perlow, "Osborne effects: Death by pre-announcement", ZDNet, 21 June 2012

- ^ Nokia's Windows Phone "bear hug" is choking the Mighty Finn - CNET

- ^ Natasha Lomas, "Windows Phone 8 sucker punches Windows Phone fans" CNET, 21 June 2012. Accessed 24 October 2017

- ^ Windows Phone 7 was doomed by design, Microsoft admits - CNET

- ^ Ando, Ritsuko; Rigby, Bill (3 September 2013). "Microsoft swallows Nokia's phone business for $7.2 billion". Reuters. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ Jason Huggins (April 2015), What Doomed MakerBot? The Osborne Effect