Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pietru Caxaro

View on Wikipedia

Pietru Caxaro or Caxaru[a] (died c. August 1485), also known in English as Peter Caxaro, was a Maltese notary, orator, politician, philosopher, and poet. He wrote the poem Cantilena, the earliest known text in the Maltese language and the only one in Medieval Maltese. Caxaro is, to date, Malta's first philosopher, according to Mark Montebello.

Little about Caxaro's life is known. Born in Mdina sometime in the early fifteenth century, Caxaro studied to become a notary and attained his qualification in 1438. He served as a judge in the civil and ecclesiastical courts for much of his life. He was also a member of the Mdina town council and appears to have been a skilled orator. Caxaro died in 1485, remaining all but forgotten for the next four centuries.

In 1966, the historian Mikiel Fsadni unearthed a Maltese language poem attributed to Caxaro, christened the Cantilena. The discovery was surprising, since, at the time, the oldest known poem in Maltese dated to the seventeenth century, and hardly any references to Maltese from the Middle Ages beyond placenames were thought to exist. Fsadni and fellow historian Godfrey Wettinger introduced the Cantilena to the public in 1968. Since then, many linguistic and literary studies on the poem have been composed. Scholars emphasise the blend of Arabic and Italian/Sicilian influences on the Maltese language that features in Caxaro's work and the humanistic philosophy it communicates. In 2025, UNESCO added the Cantilena to its Memory of the World Register, only the second Maltese artefact to receive such recognition.

Biography

[edit]Sources

[edit]Only four sources on Caxaro's biographical information are known: the State Archives of Palermo, Sicily, the National Library of Malta, the Archives of the Dominicans at Rabat, and Giovanni Francesco Abela's 1647 work Della Descrittione di Malta Isola nel Mare Siciliano.[1] As for Caxaro's own contributions and thought, mere fragments exist. Besides the Cantilena, one finds some judicial sentences he passed at the ecclesiastical courts, secretarial minutes taken at the Mdina town council meetings in which he participated, and municipal acts of the Mdina council. Caxaro's name is mentioned in at least some 267 council sittings between 1447 and 1485.[2]

Life and career

[edit]

Caxaro was born to a noble family in Mdina, Malta.[3] His date of birth is unknown,[4] although he was likely born around the beginning of the fifteenth century.[3] At the time, Malta formed part of the Crown of Aragon,[5] having succumbed to the Aragonese crown in 1282 following centuries of subjection at the hands of various empires.[6] Throughout Aragonese rule, Malta was also considered part of Sicily.[7] Caxaro's parents, Leo and Zuna,[4] were Maltese natives,[5] and he had at least one brother, Nicholas "Cola",[8] and one sister.[4] The family was possibly of Jewish descent[4] and, according to Frans Sammut, forced to convert to Christianity.[9] He resided at Mdina.[5]

Caxaro applied to become a public notary and obtained his warrant in 1438 after passing examinations held at Palermo.[4] He had spent some time in the city[5] and thus, notes Mark Montebello, grown familiar with Renaissance culture and humanist ideas.[10] Some months later, he was appointed judge at the courts of Gozo, and later the Maltese courts, for 1440 and 1441, respectively.[4] He was judge at the civil and ecclesiastical courts periodically from 1438 to 1481. Caxaro served as jurat, and sometimes secretary, in the town council of Mdina for much of the 1450s, 1460s, 1470s, and 1480s.[11] 1480 saw Caxaro involved in a controversy surrounding the bishop of Malta, who was suspected of corruption. At the Mdina council, he passionately demanded remedy from the bishop's end, for which bishop had him excommunicated and interdicted. These were later reversed.[3]

The records of the Mdina town council provide information on Caxaro’s oratorical abilities, which seem to have been impressive, but say nothing about his philosophical or poetic interests.[4] Introducing his transcription of the composition, Brandan indicated Caxaro as a "philosopher, poet and orator."[12] In Mark Montebello's view, the Cantilena's professional composition proves Caxaro's qualification as a philosopher, poet, and orator.[13] His work as a notary is more dubious, as Godfrey Wettinger doubts that it "extended any further than the making of an occasional public copy of some royal or viceregal document granting Malta one or other of the numerous privileges the island claimed," and concludes that Caxaro never served in this capacity for long, if indeed he did serve.[14]

Around August 1485, Caxaro drew up his will, and died a few days later. The precise date of his death is not known.[4] Caxaro had willed that he be buried in a Dominican chapel at Rabat dedicated to Our Lady of Divine Help, built at his instruction with his funding.[15]

Personal life

[edit]A slave owner,[5] Caxaro amassed a sizeable territorial empire.[5] This included two Mdina houses, swaths of land, a vineyard, and a farmhouse.[4] He enjoyed a good relationship with Dominican friars, who, upon arriving in Malta around 1450, sought to cultivate friendships with the professional class.[3]

Caxaro is thought to have remained a bachelor.[16] However, he did attempt to marry Franca de Biglera (née de Burdino), a widow, either in 1463 or 1478.[17] The proposal quickly faced resistance as Biglera's eldest brother claimed that Caxaro and her were spiritually related: Caxaro's father was one of Biglera's godparents at her baptism. Caxaro subsequently approached the Mdina notables to have the marriage arranged, and the bishop's court eventually gave its assent.[18] Still, Biglera apparently changed her mind,[4] as there is no evidence that the marriage ever happened.[18]

Rediscovery

[edit]Up until 1968, Caxaro was "virtually unknown."[19] Only a few modern scholarly texts had mentioned him by then, the first being Paul Galea's 1949 history of the Dominican Order in Rabat, Malta. Mikiel Fsadni also referred to him in another history of the Dominicans published in 1965. Both sourced their information on Caxaro from Francesco Maria Azzopardo's 1676 Descrittione delli Tre Conventi che I'Ordine dei Predicatori Tiene nell 'Isola di Malta (Description of the Three Convents that the Order of Dominicans Holds on the Island of Malta).[13]

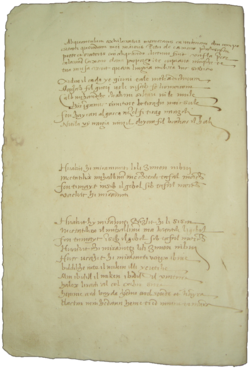

On September 22, 1966, Fsadni was conducting research at the Notarial Archives, scanning the deeds (1533–1536)[19] of the notary Brandan Caxaro.[20] There, he stumbled across a hitherto unknown document.[21] It was a Maltese poem attributed to Peter Caxaro, transcribed by Brandan.[22] After close inspection, no blemishes or inaccuracies were found.[19] He and his companion Godfrey Wettinger concluded that Caxaro's poem, dubbed the Cantilena, was originally composed in the mid-fifteenth[23] century, making it the oldest complete writing in the Maltese language.[24] This "pushed back the date of written Maltese by about two centuries";[25] at the time, the earliest Maltese poem was thought to be Giovanni Francesco Buonamico's (1639–1680) sonnet "Mejju Ġie bil-Ward u ż-Żahar".[26] Wettinger recounts that the discovery astounded them, since contemporary scholars had maintained that few writers "ever bothered with the Maltese language except for some eighteenth century 'zealots'" and some from the nineteenth century.[21] Two years later, in 1968, Fsadni and Wettinger disclosed their findings and presented the Cantilena to the public for the first time.[27] Scholars reacted enthusiastically; Mark Montebello writes that Fsadni and Wettinger's research gave "Maltese literature its greatest boost for a very long time."[19]

The Cantilena

[edit]The Cantilena is, as of the present day, the oldest text in the Maltese language[28] and the only one in Medieval Maltese. Many textual analyses of the Cantilena have been made in the past few decades. In general, the comments regard the inconsistencies which exist in the extant copy of the Cantilena. Other comments have been advanced from the perspective of literary criticism. Due to the Cantilena’s uniqueness, results have been put forward by historical linguistics, emphasising the drastic changes in the Maltese language over a span of four centuries.[29] In 2025, UNESCO added the Cantilena to the Memory of the World Register, marking the second time a Maltese artefact has received this recognition.[30]

Text

[edit]|

Original text Xideu il cada ye gireni tale nichadithicum |

English translation A recital of my misfortunes, O my neighbours, the following I shall tell you, |

Transcript

[edit]

Upon its publication in 1968, scholars found the language of the Cantilena barely comprehensible.[33] Deciphering it was, in the words of Wettinger, "terribly difficult [and] absolutely daunting."[24] Erin Serracino Inglott commented that in order to interpret the text, one had to be a philologist, familiar with Arabic, well-versed in the history of Malta, and informed on Caxaro's background.[33]

The authenticity of Caxaro's work is maintained by scholars, as with Brandan's transcription.[19] Nonetheless, some scholars have suggested that the Cantilena, in part or in whole, was not actually composed by Caxaro.[13] Fuad Kabazi views the text as Brandan Caxaro's transcription in Latin script of a Maghrebian or Andalusian qasida.[34] He bases this supposition on what he described as an "extrasensorial impression."[34]

That Brandan's transcript of the Cantilena is faulty is evident from various internal traits. Furthermore, the reasons for which Brandan recalled the work, and even the manner in which he did so, is unto this day a baffling uncertainty. The cheerfulness felt by Brandan apparently seems to be doubly caused, namely by both the memory of the composition and the memory of his ancestor (with a necessary relationship of one to the other). Brandan's opening sentence of the short prologue seems to suggest that he was gladdened more by the relationship than by any of the related parts. Wettinger and Fsadni had suggested that it was the consolation which Brandan saw in the content of the composition that prompted him to leave us a memory of it, writing it down in one of the registers of his acts.[2]

In 1986, Joseph Brincat pointed out perceived imperfections in Brandan's transcript,[35] particularly the verses which do not have any rhyme. He specifically refers here to the four lines of the refrain (vv. 7-10) and the first four lines of the second stanza (vv. 11-14). He concludes that the quatrain which stands on its own between the two stanzas, of six verses and ten verses each respectively, is erroneously transcribed by Brandan.[35] Brincat provides convincing internal evidence for the error,[36] and other scholars subscribe to his conclusion.[37]

Analysis

[edit]Contextual

[edit]The main idea of the text, the so-called "physical interpretation,"[38] goes as follows: an uncontrollable person had been responsible for the collapse of a building which the author considered to be his.[33] In other words, he had misjudged the situation. The theme seems to follow a definite scheme, namely, an apparently simple one:[39] an invocation (vv. 1-2), the narration of an unhappy love event and the lyric I's situation thereby (vv. 3-6), its delusion (vv. 7-10, 11-14), and finally its attempt to reverse the misfortune (vv. 15-20). It is a scheme which in its content resembles the general classical Semitic (specifically Arabic) qasida pattern.[33]

As from the beginning of 1450, the Mdina town-council had been discussing the precarious state of the town walls (the mirammerii) of Mdina. In March of that same year, the Augustinian Matteo di Malta had been commissioned as the town-council's ambassador to lead the talks with the viceroy on the question so as to provide funds for their urgent restoration. Little, if any, progress seems to have been made on the matter, until at the beginning of 1454 an internal tower of the castle at Mdina collapsed. So as to take immediate action and prevent further immanent collapse of the walls, at the town-council sitting of January 11 Peter Caxaro, acting as secretary, spoke in favour of an urgent collecta (which was later effected), with the approval of the whole house. Furthermore, on May 24, Nicholas Caxaro, Peter's brother, had been appointed by the council as supramarammerius to supervise the restoration of the walls. On that occasion, Peter Caxaro had highly praised the decision taken. Strictly by way of speculation, the Cantilena might have been inspired from that serious occasion, which was the effect of a general negligence.[40]

Apart from the immediate and superficial message, there is a more profound and veiled communication. The overall drift of this so-called "metaphysical interpretation," has been seen to be the ruin of the author's project, either concerning his career or a love affair. The general melancholic tone of the composition did not pass unnoticed, though it had been recognised that the final note sounded the victory of hope over desperation; the building anew over the ruins of unfulfilled dreams or ambitions.[41]

Wettinger denies that the murder of Caxaro's brother had any relevance to the theme of the Cantilena.[8] On the other hand, he proposed that it may have to do with Caxaro's marriage proposal which apparently went up in smoke.[42] The suggestion had been confirmed jointly by Wettinger and Fsadni in 1983.[43]

Some have stated that the composition has no depth of feeling at all. Others have indeed valued its content highly, wisely noting that the subject is entirely profane (as opposed to the sacred), and moreover sheds light on the concrete versus abstract thinking of the populace (a feature common amongst Mediterranean peoples unto this day); reality against illusion.[43]

Linguistic

[edit]Ġużè Chetcuti notes that the Cantilena demonstrates that "even during such a distant time, there were individuals who felt the urge to express themselves in their nation's tongue."[44]

Literary

[edit]The verses in the Cantilena appear to contain eleven syllables each.[45] According to Oliver Friggieri, they evoke Spanish mosarabic verse.[45] Frans Sammut suggests that the Cantilena was a zajal, an Arabic term for a song which Spanish and Sicilian Jews adopted and promoted.[9]

Philosophy

[edit]

In his prologue to the Cantilena, Brandan Caxaro confers upon his uncle the title of philosopher. Some scholars interpret this title as denoting a wise man or sophist rather than an actual philosopher, but Mark Montebello maintains that Caxaro must be understood literally.[46] Pietru Caxaro's philosophy is manifested in one sole document, the Cantilena, "a fragment of his thought"; similar cases spring up with other philosophers, such as Aristotle.[47]

Montebello considers Caxaro the first Maltese philosopher.[19] According to him, Caxaro's cultural background and philosophical thought "reflect the peculiar force, functions and needs of a Mediterranean people whose golden age had still to come, but whose mental constitution and mode of expression were readily set."[19]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Maltese pronunciation: ['piːtruː kɐ'ʃɐːrɔ, -rʊ] PEE-troo cah-SHAH-raw, -roo

- ^ Numerous transliterations of the Cantilena have been made, each with varying spellings. Montebello 1992, p. 24, citing Brincat 1986, omits the second stanza entirely.

References

[edit]- ^ Montebello 1992, pp. 16–17

- ^ a b Montebello 1992, pp. 17–18

- ^ a b c d Montebello 2001, pp. 74–75

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Schiavone 2023

- ^ a b c d e f Montebello 1992, p. 17

- ^ Luttrell 1965, pp. 4–5

- ^ Luttrell 1965, p. 7

- ^ a b Wettinger 1978, p. 97

- ^ a b Sammut 2009

- ^ Montebello 1992, pp. 21–22

- ^ Wettinger & Fsadni 1983, pp. 22–24

- ^ Wettinger 1978, p. 90

- ^ a b c Montebello 1992, p. 16

- ^ Wettinger 1978, p. 95

- ^ Montebello 1992, p. 12

- ^ Schiavone 2023; Wettinger 1978, p. 96

- ^ Wettinger 1978, pp. 95–96

- ^ a b Wettinger 1978, p. 96

- ^ a b c d e f g Montebello 1992, p. 15

- ^ Vella 2015

- ^ a b Wettinger 1978, p. 88

- ^ Wettinger 1978, pp. 90–91

- ^ Wettinger & Fsadni 1968, p. 32

- ^ a b Wettinger 1978, p. 92

- ^ Grima 2021

- ^ Cassar 2017, pp. 77, 87

- ^ Montebello 1992, p. 15; Vella 2015

- ^ Chetcuti 1985, p. 156; Wettinger in Montebello 1992, p. 11

- ^ Montebello 1992, p. 23

- ^ Cummings 2025

- ^ Wettinger & Fsadni 1968, pp. 36–38

- ^ Luttrell 1975, p. 67

- ^ a b c d Montebello 1992, p. 24

- ^ a b Kabazi 1990, p. 42

- ^ a b Brincat 1986, p. 11

- ^ Brincat 1986, pp. 13–14

- ^ Cassola 1986, p. 119

- ^ Bin-Bovingdon 1978, p. 117

- ^ Bonnici 1990, p. 46

- ^ Montebello 1992, pp. 37–38 n. 97

- ^ Montebello 1992, pp. 24–25

- ^ Wettinger 1978, pp. 95–96

- ^ a b Montebello 1992, p. 25

- ^ Chetcuti 1985, p. 156

- ^ a b Friggieri 1998, p. 123

- ^ Montebello 1992, p. 18

- ^ Montebello 1992, p. 19

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Chetcuti, Ġużè (1985). Stilistika Maltija u Movimenti Letterarji [Maltese Stylistics and Literary Movements] (in Maltese). Valletta, Malta: Klabb Kotba Maltin.

- Luttrell, Anthony T. (1975). "Approaches to Medieval Malta". In Luttrell, Anthony T. (ed.). Medieval Malta: Studies on Malta Before the Knights (PDF). London, England: The British School at Rome. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Montebello, Mark F., ed. (1992). Pietru Caxaru u l-Kantilena Tiegħu [Peter Caxaro and His Cantilena] (in Maltese). Malta.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Montebello, Mark F. (2001). Il-Ktieb Tal-Filosofija F'Malta, L-Ewwel Volum (A–L) [The Book of Philosophy in Malta, The First Volume (A–L)] (in Maltese). Vol. 1. Malta: Kullana Kultura. ISBN 9990941823.

- Wettinger, Godfrey; Fsadni, Mikiel (1968). Peter Caxaro's Cantilena: A Poem in Medieval Maltese. Malta: Lux Press.

- Wettinger, Godfrey; Fsadni, Mikiel (1983). L-Għanja ta' Pietru Caxaru: Poeżija bil-Malti Medjevali [The Song of Peter Caxaro: A Poem in Medieval Maltese] (in Maltese). Malta.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Journals

[edit]- Bin-Bovingdon, Rodrig (1978). "Further Comments on Peter Caxaro's Cantilena" (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies. 12: 106–118 – via University of Malta.

- Bonnici, Thomas (1990). "Galician–Portuguese Traits in Caxaro's Cantilena" (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies. 19–20: 46–51 – via University of Malta.

- Brincat, Joseph (1986). "Critica Testuale della Cantilena di Pietro Caxaro" [Textual Criticism of Peter Caxaro's Cantilena] (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies (in Italian). 16: 1–21 – via University of Malta.

- Cassar, Carmel (2001). "Malta: Language, Literacy and Identity in a Mediterranean Island Society" (PDF). National Identities. 3 (3): 257–275. Bibcode:2001NatId...3..257C. doi:10.1080/14608940120086902 – via University of Malta.

- Cassar, Carmel (2017). "Giovan Francesco Buonamico: Insights into Travel and Cultural Practices in Seventeenth-Century Malta" (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies. 29: 77–90 – via University of Malta.

- Cassola, Arnold (1983). "On the Meaning of Gueri in Petrus Caxaro's Canilena" (PDF). Melita Historica. 8 (4): 315–317 – via Malta Historical Society.

- Cassola, Arnold (1986). "Sull'Autore dei vv. 11-14 della Cantilena di Petrus Caxaro" [On the Author of vv. 11-14 of Peter Caxaro's Cantilena] (PDF). Melita Historica (in Italian). 9 (3): 199–202 – via University of Malta.

- Cassola, Arnold (1998). "Two Notes: Brighella and Thezan; the "Cantilena", Maltese and Sicilian Proverbs" (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies. 25–26: 58–66 – via University of Malta.

- Cowan, William (1975). "Caxaro's Cantilena: A Checkpoint for Change in Maltese" (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies. 10: 4–10 – via University of Malta.

- Friggieri, Oliver (1993). "Main Trends in the History of Maltese Literature". Neohelicon. 22 (2): 59–69 – via University of Malta.

- Friggieri, Oliver (1998). "L-Istorja tal-Poeżija Maltija" [The History of Maltese Poetry] (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies (in Maltese). 25–26: 122–145 – via University of Malta.

- Friggieri, Oliver (2000). "Il romanticismo italiano e l'inizio della poesia Maltese" [Italian romanticism and the beginning of Maltese poetry]. Rassegna Apulia (in Italian). 4: 135–148 – via University of Malta.

- Kabazi, Fuad (1990). "Ulteriori Considerazioni Linguistiche sulla Cantilena di Pietro Caxaro" [Further Linguistic Remarks on Peter Caxaro's Cantilena] (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies (in Italian). 19–20: 42–45 – via University of Malta.

- Luttrell, Anthony T. (1965). "Malta and the Aragonese crown: 1282-1530" (PDF). Journal of the Faculty of Arts. 3 (1): 1–9 – via University of Malta.

- Wettinger, Godfrey (1978). "Looking back on 'The Cantilena of Peter Caxaro'" (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies. 12: 88–105 – via University of Malta.

- Wettinger, Godfrey (1979). "Late Medieval Judaeo-Arabic poetry in Vatican MS. 411" (PDF). Journal of Maltese Studies. 13: 1–16 – via University of Malta.

- Wettinger, Godfrey (1980). "Honour and Shame in Late Fifteenth Century Malta" (PDF). Melita Historica. 8 (1): 65–77 – via University of Malta.

News articles

[edit]- Cummings, James (19 April 2025). "Oldest work of Maltese literature added to prestigious UNESCO heritage list". Times of Malta. Retrieved 8 September 2025.

- Grima, Joseph F. (22 August 2021). "It happened in August: Peter Caxaro and his Cantilena". Times of Malta. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- Magri, Giulia (12 July 2025). "This 500-year-old poem is the oldest piece of literature in Maltese". Times of Malta. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- Montebello, Mark F. (22 May 2016). "Cantilena structure more complex than believed". Times of Malta. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- Sammut, Frans (19 April 2009). "Il-Kantilena ta' Caxaro u l-Imdina: Poeżija waħdanija tal-Medjuevu" [The Cantilena of Caxaro and Mdina: A solitary medieval poem]. Il-Mument (in Maltese). pp. 8–10.

- Schiavone, Michael (1 August 2023). "Biography: Pietro Caxaro". Times of Malta. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- Vella, Matthew (16 June 2015). "'Fsadni hid Caxaro's Cantilena from Wettinger for three months'". Malta Today. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

External links

[edit]- The Cantilena read in the original Medieval Maltese