Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Memory of the World Programme

View on Wikipedia

UNESCO's Memory of the World (MoW) Programme is an international initiative that recognises documentary heritage of global importance. It aims to safeguard the documentary heritage of humanity against collective amnesia, neglect, decay over time and climatic conditions, as well as deliberate destruction. It calls for the preservation of valuable archival holdings, library collections, and private individual compendia all over the world for posterity and increased accessibility to, and public awareness of, these items.[1][2][3]

Following the establishment of the Memory of the World International Register, UNESCO and the Memory of the World Programme have encouraged the creation of autonomous national and regional committees as well as national and regional registers which focus on documentary heritage of great regional or national importance, but not necessarily of global importance.[4]

Memory of the World International Register

[edit]The Memory of the World International Register is a list of the world's documentary heritage with outstanding global significance – such as manuscripts, oral traditions, audio-visual materials, and library and archive holdings.[6] It catalogues documentary heritage that has been recommended by the International Advisory Committee and endorsed by the Director-General of UNESCO, using the selection criteria "world significance and outstanding universal value."[7] As well as raising awareness of this heritage, the register aims to promote its preservation, digitization, and dissemination by calling upon the programme's networks of experts.[3] The program also uses technology to provide wider accessibility and diffusion of information about the items inscribed on the register.[3]

The first inscriptions on the International Register were made in 1997.[1][3][8] The various properties in the register include recordings of folk music; ancient languages and phonetics; aged remnants of religious and secular manuscripts; collective lifetime works of renowned giants of literature; science and music; copies of landmark motion pictures and short films; and accounts documenting changes in the world's political, economic, and social stage.

As of April 2025, 570 pieces of documentary heritage had been inscribed in the International Register.[9]

The program is not without controversy. During the 2015 cycle, for example, there was a significant degree of conflict within East Asia, as registry with the MoW Program was becoming viewed as an approval of particular views of contested history, specifically with respect to the Nanjing Massacre and the comfort women.[10]

| Region | Number of inscriptions to the Register |

|---|---|

| Memory of the World Register – Africa | 35 |

| Memory of the World Register – Arab States | 17 |

| Memory of the World Register – Asia and the Pacific | 154 |

| Memory of the World Register – Europe and North America | 274 |

| Memory of the World Register – Latin America and the Caribbean | 77 |

| Memory of the World Register – Other | 7 |

| Total | 496 |

Top 10 countries by number of inscriptions

[edit]| Rank | Country | Number of inscriptions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33 | |

| 2 | 27 | |

| 3 | 26 | |

| 4 | 22 | |

| 5 | 20 | |

| 6 | 19 | |

| 7 | 18 | |

| 8 | 17 | |

| 9 | 16 | |

| 9 | 16 | |

| 11 | 13 |

Process

[edit]Any organization or individual can nominate a documentary item for inscription on the International Register via UNESCO Member States through their National Commission for UNESCO. In the absence of a National Commission, the nomination is sent through the relevant government body in charge of relations with UNESCO, involving, if one exists, the relevant national MoW committee.[11] Two proposals per UNESCO Member State are considered in each nomination cycle. There is no limit on joint nomination proposals from two or more UNESCO Member States.

The program is administered by the International Advisory Committee (IAC), whose 14 members are appointed by the Director-General of UNESCO.[6][3] During its meetings, the IAC examines the full documentation of the item's description, origin, world significance, contemporary state of conservation and other criteria for admissibility. The IAC recommends to the Executive Board of UNESCO the items proposed for inscription.[12] The IAC is responsible for the formulation of major policies, including the technical, legal and financial framework for the program. It also maintains several subsidiary bodies:[13]

- Bureau: Maintains an overview of the Programme between IAC meetings and makes tactical decisions in liaison with the Secretariat, reviews the use of the Memory of the World logo, and liaises with national Memory of the World committees and monitors their growth and operation.

- The Preservation Sub-Committee: Develops, regularly revises and promulgates information guides on the preservation of documentary heritage, and offers advice on technical and preservation matters.

- Register Sub-Committee: Oversees the assessment of nominations for the Memory of the World International Register and provides recommendations, with reasons, for their inscription or rejection to each meeting of the IAC.

- Education and Research Sub-committee: Develops strategies and concepts for institutionalizing education and research on documentary heritage and helps developing innovative curricula and research on Memory of the World.

- The Secretariat at UNESCO: Provides support services to the International Advisory Committee (IAC) and its subsidiary bodies, and the general administration and monitoring of the Program. It is the contact point of the Program.[14]

- The Memory of the World Programme is implemented by UNESCO through regional and national committees. These committees are autonomous from UNESCO and are composed of dedicated local heritage professionals.[15]

National and regional registers

[edit]Some national and regional Memory of the World committees maintain their own Memory of the World registers, highlighting documentary heritage of great national or regional importance.[16][17] National registers include:

- Brazil Memory of the World Register

- Canada Memory of the World Register[18][19]

- Mexican National Register of the Memory of the World[20]

- Memory of the World Aotearoa New Zealand Ngā Mahara o te Ao

- Philippines Memory of the World Register

- UK Memory of the World Register

There are presently two regional registers: the Asia Pacific Regional Register and the Latin America and the Caribbean regional register'[17][21]

The Asia Pacific Regional Register and the Register for Latin America and the Caribbean[22] have already honoured important documentary heritage of their regions, while the African Regional Register is currently being established.[23] In the Asia-Pacific region, in 2014–2015, there were 18 member nations of MOWCAP (6 without national committees), while in 2016, there were 16 national MoW committees.[10]

Jikji Prize

[edit]

The Jikji Prize was established in 2004 by UNESCO[24] in cooperation with the South Korean government to further promote the objectives of the Memory of the World Programme, and to commemorate the 2001 inscription of the country's Jikji on the Register.[25] The award, which includes a cash prize of $30,000 from the Korean government, recognizes institutions that have contributed to the preservation and accessibility of documentary heritage.[26]

The prize has been awarded biannually since 2005 during the meeting of the IAC.[26]

Recipients

[edit]- 2005: Czech National Library (Prague)[26][27]

- 2007: Phonogrammarchiv of the Austrian Academy of Sciences

- 2009: National Archives of Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur)[28]

- 2011: National Archives of Australia[29]

- 2013: Apoyo al Desarrollo de Archivos y Bibliotecas (Mexico City)

- 2016: Iberarchivos Programme for the Development of Ibero-Ameran Archives

- 2018: SAVAMA-DCI (Mali)

- 2020: Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum (Cambodia)[30]

- 2022: American University in Cairo's Libraries and Learning Technologies, Rare Books and Special Collection Library in Egypt[31]

- 2024: National Library of Indonesia[32]

History

[edit]In 1992, the program began as a way to preserve and promote documentary heritage, manuscripts, maps, rock inscriptions, court documents, diplomatic exchanges and more that are deemed to be of such global significance as to transcend the boundaries of time and culture.[6] This recorded memory reflects the diversity of languages, people, and cultures.[26] UNESCO, the world agency responsible for the protection of the world's cultural and natural heritage, realized the need to protect such fragile yet important component of cultural heritage. The Memory of the World Programme was established to facilitate the preservation of, universal access to, and public awareness about humanity's documentary heritage.[33]

People the world over are creating [memories] in forms that are less and less permanent—be it sound recordings, film, videotape, newsprint, photographs, or computer-based documents. It must be said that the output of the present century alone is probably greater than the total output of all previous centuries put together; and ironically and tragically, it is being lost faster than ever before. It is a tragedy indeed, for what is at stake is the recorded memory of mankind.

— Dato' Habibah Zon, Director-General of the National Archives of Malaysia, [6]

Regular meetings were held by the IAC in its interim capacity beginning in 1993, culminating in the creation of the Memory of the World International Register during its second meeting in 1995,[6][8] with the first inscriptions on the register in 1997, after the statutes that created the IAC as a standing committee took effect.[34]

Memory of the World IAC meetings

[edit]Biennial meetings of the International Advisory Committee are used to discuss and inscribe items onto the register. The meeting normally takes place in odd-numbered years:

| IAC Session | Date | Site | IAC chairperson | Number of nominations evaluated | Number of inscriptions to the register | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 1993 Sept 12–14 |

Pułtusk, Poland | Jean-Pierre Wallot (Canada)[34] | none | none | [6] |

| 2nd | 1995 May 3–5 |

Paris, France | Jean-Pierre Wallot (Canada)[8] | none | none | [6] |

| 3rd | 1997 Sept 29 – Oct 1 |

Tashkent, Uzbekistan | Jean-Pierre Wallot (Canada) | 69 | 38 | [6][8] |

| Bureau Meeting | 1998 Sept 4–5 |

London, United Kingdom | Jean-Pierre Wallot (Canada) | none | none | [6] |

| 4th | 1999 Jun 10–12 |

Vienna, Austria | Bendik Rugaas (Norway) | 20 | 9 | [34] |

| 5th | 2001 Jun 27–29 |

Cheongju, South Korea | Bendik Rugaas (Norway) | 42 | 21 | [35] |

| 6th | 2003 Aug 28–30 |

Gdańsk, Poland | Ekaterina Genieva (Russian Federation) | 41 | 23 | [3][36] |

| 7th | 2005 Jun 13–18 |

Lijiang, China | Deanna B. Marcum (US) | 53 | 29 | [26][27] |

| 8th | 2007 Jun 1–15 |

Pretoria, South Africa | Alissandra Cummins (Barbados) | 53 | 38 | [33][37] |

| 9th | 2009 Jul 27–31 |

Bridgetown, Barbados | Roslyn Russell (Australia) | 55 | 35 | [38][39] |

| 10th | 2011 May 22–25 |

Manchester, United Kingdom | Roslyn Russell (Australia) | 84 | 45 | [40] |

| 11th | 2013 Jun 18–21 |

Gwangju, South Korea | Helena R Asamoah-Hassan (Ghana) | 84 | 56 | [41] |

| 12th | 2015 Oct 4–6 |

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates | Abdulla El Reyes (United Arab Emirates) | 86 | 44 | [42] |

| 13th | 2017 Oct 24–27 |

Paris, France | Abdulla El Reyes (United Arab Emirates) | 132 | 78 | [43] |

| 14th | 2023 Mar 8–10, Apr 11 |

Paris, France + online | 88 | 64 | [44] | |

| 15th | 2025 Feb 26–28 |

Paris, France | 122 | 74 | [45] |

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Edmondson, Ray (2020). "Memory of the World: An Introduction". In Edmondson, Ray; Jordan, Lothar; Prodan, Anca Claudia (eds.). The UNESCO Memory of the World Programme: Key Aspects and Recent Developments. Cham: Springer. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-3-030-18441-4.

- ^ "Official website". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. Retrieved 2025-06-17.

- ^ a b c d e f "Twenty-three new inscriptions on Memory of the World Register of Documentary Collections". UNESCO Press. 2003-09-01. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ UNESCO. "MoW Committees". UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-06-23.

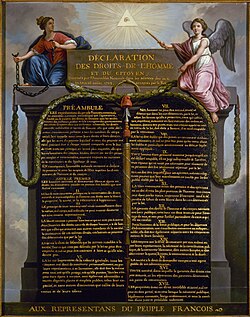

- ^ "Original Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789–1791)". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "UNESCO Memory of the World Programme: The Asia-Pacific Strategy". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. Archived from the original on 2005-02-28. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- ^ "Memory of the World: Documentary heritage treasures of Africa". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 12 December 2023. Archived from the original on 2025-02-17. Retrieved 2025-06-17.

- ^ a b c d "Third Meeting of the International Advisory Committee of the Memory of the World Programme, Tashkent, 29 September-1st October 1997: final report". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. October 1997. Retrieved 2025-06-17.

- ^ "Memory of the World". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. Retrieved 2025-04-24.

- ^ a b Yamamoto, Mayumi (2016). "Heritage and Diplomacy: A Cultural Approach to UNESCO's Document Registry Program in East Asia". Annual Journal of Cultural Anthropology. 11. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ UNESCO. "Memory of the World General Guidelines" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-06-23.

- ^ "General Guidelines of the Memory of the World (MoW) Programme". UNESCO. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ "International Advisory Committee". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2009-08-11. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ UNESCO. "Secretariat". UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-06-23.

- ^ "MoW Committees". UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-06-23.

- ^ "Unlocking the Past, Shaping the Future: UNESCO's Memory of the World Registers for Collective Memory". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. Retrieved 15 July 2025.

- ^ a b Russell, Roslyn (2020). "The Memory of the World Registers and Their Potential". In Edmondson, Ray; Jordan, Lothar; Prodan, Anca Claudia (eds.). The UNESCO Memory of the World Programme: Key Aspects and Recent Developments. Cham: Springer. p. 44. ISBN 978-3-030-18441-4.

- ^ Monkman, Lenard (11 September 2019). "National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation archives added to UNESCO world register". CBC. Archived from the original on 2023-12-05. Retrieved 2025-06-17.

- ^ "Canada Memory of the World Register". Canadian Commission for UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-06-17.

- ^ UNESCO. "National Register of the Memory of the World incorporates 14 new inscriptions". UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-06-23.

- ^ Memory of the World Committee for Asia and the Pacific. "MOWCAP Regional Register". Memory of the World Committee for Asia and the Pacific. Retrieved 2025-06-23.

- ^ UNESCO. "Regional Register". UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-06-23.

- ^ Africa Regional Committee of the Memory of the World Programme (ARCMoW). "Africa Regional Committee of the Memory of the World Programme (ARCMoW)". Africa Regional Committee of the Memory of the World Programme (ARCMoW). Retrieved 2025-06-23.

- ^ UNESCO. "UNESCO/Jikji Memory of the World Prize". UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-06-23.

- ^ UNESCO. "About the Prize". UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-06-23.

- ^ a b c d e "Twenty-nine new documentary collections inscribed on the Memory of the World Register". UNESCO Press. 2005-06-21. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ a b "Seventh Meeting of the International Advisory Committee of the Memory of the World Programme". UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ "UNESCO/Jikji Memory of the World 2009 Prize awarded to National Archives of Malaysia". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2009-08-21. Archived from the original on 2015-03-14. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- ^ "National Archives of Australia to receive UNESCO/Jikji Memory of the World Prize". UNESCO News Service. 2011-05-30. Archived from the original on 2015-03-14. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "UNESCO / Jikji Memory of the World Prize 2020 awarded to the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum (Cambodia)". UNESCO. April 9, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "The American University in Cairo to receive 2022 UNESCO/Jikji Memory of the World Prize | UNESCO". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ "The National Library of Indonesia to receive 2024 UNESCO-Jikji Memory of the World Prize". UNESCO. September 3, 2024. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

- ^ a b Jasmina Sopova (2007-06-20). "Thirty-eight new inscriptions for Memory of the World Register". UNESCO Press. Archived from the original on 2009-11-11. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ a b c "Fourth meeting of the International Advisory Committee of the Memory of the World Programme, Vienna, 10-12 June 1999: final report". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. July 1999. Retrieved 2025-06-17.

- ^ "Fifth Meeting of the International Advisory Committee of the Memory of the World Programme". UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ "Sixth Meeting of the International Advisory Committee of the Memory of the World Programme". UNESCO. Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ "Eighth Meeting of the International Advisory Committee of the Memory of the World Programme". UNESCO. 2007. Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ Joie Springer (2007-06-20). "Thirty-eight new inscriptions for Memory of the World Register". UNESCO Press. Archived from the original on 2015-03-14. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ "9th Meeting of the International Advisory Committee of the Memory of the World Programme, Christ Church, Barbados, 29-31 July 2009: report". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. December 2009. Retrieved 2025-06-17.

- ^ "10th Meeting of the International Advisory Committee Memory of the World Programme Manchester, United Kingdom, 22–25 May 2011 Report". UNESCO. 2011. Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ "54 new inscriptions on UNESCO Memory of the World Register". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2013. Retrieved 2025-06-17.

- ^ "12th Meeting of the International Advisory Committee of the Memory of the World Programme, 4-6 October 2015, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: final report". unesdoc.unesco.org. October 2015. Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ "Report of 13th Meeting of the International Advisory Committee (IAC), UNESCO, Paris, 24-27 October 2017". unesdoc.unesco.org. November 2017. Retrieved 2025-06-17.

- ^ "Nominations of new items of documentary heritage to be inscribed on the Memory of the World international register: list of nominations". unesdoc.unesco.org. 14 April 2023. Retrieved 2023-05-18.

- ^ "Nominations of new items of documentary heritage to be inscribed on the Memory of the World International Register: list of nominations". unesdoc.unesco.org. 18 March 2025. Retrieved 2025-06-17.

Further reading

[edit]- Buckley, Kristal; Darian-Smith, Kate (2023). "International Conflict, National Pasts, and UNESCO World Heritage and Memory of the World". In Sluga, Glenda; Darian-Smith, Kate; Herren, Madeleine (eds.). Sites of International Memory. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 294–320. doi:10.2307/j.ctv2zjz7d9.16. ISBN 978-1-5128-2406-3. OCLC 1376193602.

External links

[edit]Memory of the World Programme

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Objectives

Establishment and Initial Rationale

The UNESCO Memory of the World Programme was established in 1992 as an initiative to safeguard documentary heritage of global significance.[2] It emerged from UNESCO's recognition of the urgent need to address the deteriorating condition of archival and library materials worldwide, particularly in regions affected by conflict, neglect, and technological obsolescence.[1] The programme's formal launch responded to a 1991 report commissioned by UNESCO, which highlighted the vulnerability of humanity's written and audiovisual records to irreversible loss.[9] The initial rationale centered on combating "collective amnesia," a term used to describe the risk of losing irreplaceable sources of human knowledge and cultural identity due to inadequate preservation efforts.[1] Proponents argued that while physical monuments received attention through initiatives like the World Heritage Convention, documentary heritage—encompassing manuscripts, films, and recordings—lacked comparable international mechanisms, leading to disproportionate destruction in events such as wars and natural disasters.[10] This focus was driven by empirical observations of heritage losses, including the burning of libraries in the former Yugoslavia and the decay of acetate-based media in archives, underscoring the causal link between poor stewardship and cultural erasure.[9] Early priorities emphasized not only physical conservation but also digital accessibility and international cooperation to prevent biased or selective memory formation, though implementation has varied by member states' capacities.[2] The programme's architects positioned it as a complementary effort to UNESCO's broader cultural mandates, prioritizing evidence-based selection over political considerations to ensure the preservation of diverse, verifiable historical records.[1]Core Principles and Selection Criteria

The Memory of the World Programme operates on the principle that the world's documentary heritage constitutes a shared resource belonging collectively to humanity, requiring comprehensive preservation, protection, and unrestricted accessibility to prevent cultural and informational loss.[11] This vision underscores the programme's mission to heighten global awareness of documentary heritage's value while promoting its safeguarding against threats such as destruction, decay, or inaccessibility.[11] Documentary heritage is defined as individual items or collections possessing significant, enduring value to communities, cultures, nations, or humanity at large, where their deterioration or disappearance would represent a profound impoverishment of collective memory.[11] Key objectives include applying suitable preservation techniques to mitigate risks, enabling universal access through analogue or digital means, and fostering international dialogue to enhance mutual understanding among diverse groups.[11] The programme advances these goals via five primary strategies: systematic identification of at-risk heritage, active preservation efforts, promotion of access policies, development of supportive legal and institutional frameworks, and encouragement of collaborative networks at national and international levels.[11] These principles emphasize empirical assessment of heritage's vulnerability and the causal links between neglect and irreversible loss, prioritizing actions grounded in verifiable threats rather than symbolic gestures. Selection for inscription on the International Register demands demonstration of authenticity, integrity, and world significance, evaluated through a rigorous process by the Register Sub-Committee and International Advisory Committee.[11] Authenticity requires proof of genuineness via provenance, content consistency, and material analysis, while integrity assesses completeness and unaltered state, excluding items that are fragmentary or heavily restored unless such conditions enhance rather than diminish value.[11] Primary criteria focus on world significance, requiring nominees to exhibit:- Historical influence: Direct relation to pivotal global events, figures, or processes that have shaped human history.[11]

- Form and style: Exceptional physical, artistic, linguistic, or technical qualities that exemplify innovation or mastery.[11]

- Social, spiritual, or community dimensions: Profound relevance to the identities, beliefs, or experiences of specific populations with broader human implications.[11]

.png/250px-Unesco_Memory_of_the_World_Logo_(English).png)

.png)