Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

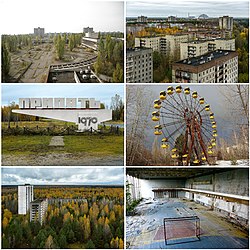

Pripyat

View on WikipediaThis article is missing information about Geography. (May 2024) |

Pripyat,[a] also known as Prypiat,[b] is an abandoned industrial city in Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine, located near the border with Belarus. Named after the nearby river, Pripyat, it was founded on 4 February 1970 as the ninth atomgrad ('atom city', a type of closed city in the Soviet Union that served the purpose of housing nuclear workers near a plant), catering the nearby Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. The plant is located north of the abandoned city of Chernobyl, after which it is named.[3] Pripyat was officially proclaimed a city in 1979 and had ballooned to a population of 49,360[4] by the time it was evacuated on the afternoon of 27 April 1986, one day after the Chernobyl disaster.[5]

Key Information

Although it is located in Vyshhorod Raion, the abandoned municipality is administered directly from the capital of Kyiv. Pripyat is supervised by the State Emergency Service of Ukraine which manages activities for the entire Chernobyl exclusion zone. Following the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the entire population of Pripyat was moved to the purpose-built city of Slavutych.

History

[edit]Early years

[edit]

Access to Pripyat, unlike cities of military importance, was not restricted before the disaster as the Soviet Union deemed nuclear power stations safer than other types of power plants. Nuclear power stations were presented as achievements of Soviet engineering, harnessing nuclear power for peaceful projects. The slogan "peaceful atom" (Russian: мирный атом, romanized: mirnyy atom) was popular during those times. The original plan had been to build the plant only 25 km (16 mi) from Kyiv, but the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, among other bodies, expressed concern that would be too close to the city. As a result, the power station and Pripyat[6] were built at their current locations, about 100 km (62 mi) from Kyiv.[7]

Post-Chernobyl disaster

[edit]

In 1986, the city of Slavutych was constructed to replace Pripyat. After Chernobyl, this was the second-largest city for accommodating power plant workers and scientists in the Commonwealth of Independent States.

One notable landmark often featured in photographs in the city and visible from aerial-imaging websites is the long-abandoned Ferris wheel located in the Pripyat amusement park, which had been scheduled to have its official opening five days after the disaster, in time for May Day celebrations.[8][9] The Azure Swimming Pool and Avanhard Stadium are two other popular tourist sites.

On 4 February 2020, former residents of Pripyat gathered in the abandoned city to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Pripyat's establishment. This was the first time former residents returned to the city since its abandonment in 1986.[10] The 2020 Chernobyl Exclusion Zone wildfires reached the outskirts of the town, but they did not reach the plant.[11]

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the city was occupied by Russian forces during the Battle of Chernobyl after several hours of heavy fighting.[12] On 31 March Russian troops withdrew from the plant and other parts of Kyiv Oblast.[13][14] On 3 April Ukrainian troops retook control of Pripyat.[15][16]

Infrastructure and statistics

[edit]The following statistics are from 1 January 1986.[17]

- The population was 49,400. The average age was about 26 years old. Total living space was 658,700 m2 (7,090,000 sq ft): 13,414 apartments in 160 apartment blocks, 18 halls of residence accommodating up to 7,621 single males or females, and eight halls of residence for married or de facto couples.

- Education: 15 kindergartens and elementary schools for 4,980 children, and five secondary schools for 6,786 students.

- Healthcare: one hospital could accommodate up to 410 patients, and three clinics.

- Trade: 25 stores and malls; 27 cafes, cafeterias, and restaurants collectively could serve up to 5,535 customers simultaneously. 10 warehouses could hold 4,430 tons of goods.

- Culture: the Palace of Culture Energetik; a cinema; and a school of arts, with eight different societies.

- Sports: 10 gyms, 10 shooting galleries, three indoor swimming-pools, two stadiums.

- Recreation: one park, 35 playgrounds, 18,136 trees, 33,000 rose plants, 249,247 shrubs.

- Industry: four factories with annual turnover of 477,000,000 rubles. One nuclear power plant with four reactors (plus two more planned).

- Transportation: Yanov railway station, 167 urban buses, plus the nuclear power plant car park with 400 spaces.

- Telecommunication: 2,926 local phones managed by the Pripyat Phone Company, plus 1,950 phones owned by Chernobyl power station's administration, Jupiter plant, and Department of Architecture and Urban Development.

Safety

[edit]

A concern is whether it is safe to visit Pripyat and its surroundings. The Zone of Alienation is considered relatively safe to visit, and several Ukrainian companies offer guided tours around the area. In most places within the city, the level of radiation does not exceed an equivalent dose of 1 μSv (one microsievert) per hour.[18]

Unrelated to the 1986 nuclear disaster, but still very much a safety concern, is the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine; Russian forces briefly occupied the Chernobyl area in 2022, before being forced out again by the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Climate

[edit]The climate of Pripyat is designated as Dfb (Warm-summer humid continental climate) on the Köppen Climate Classification System.[19]

| Climate data for Pripyat | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −3 (27) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

23.9 (75.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

11.6 (53.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.1 (21.0) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

0.1 (32.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −9.1 (15.6) |

−9 (16) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

8.6 (47.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

| Source: [20] | |||||||||||||

In popular culture

[edit]Films

[edit](Alphabetical by title)

- The horror film Chernobyl Diaries (2012) was inspired by the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 and takes place in Pripyat.[21]

- The majority of the film Land of Oblivion (2011) was shot on location in Pripyat.

- Pripyat is featured in the History Channel documentary Life After People.

- The drone manufacturer DJI produced Lost City of Chernobyl (May 2015), a documentary film about the work of photographer and cinematographer Philip Grossman and his five-year project in Pripyat and the Zone of Exclusion.[22]

- Filmmaker Danny Cooke used a drone to capture shots of the abandoned amusement park, some residential shots of decaying walls, children's toys, and gas masks, and collected them in a 3-minute short film Postcards From Chernobyl (released in November 2014), while making footage for the CBS News 60 Minutes episode "Chernobyl: The Catastrophe That Never Ended" (early 2014).[23][24]

- With the help of drones, aerial views of Pripyat were shot and later edited to appear as a deserted London in the film The Girl with All the Gifts (2016).[25]

- The documentary White Horse (2008) was filmed in Pripyat.[26]

Literature

[edit](Alphabetical by artist)

- Markiyan Kamysh's novel, Stalking the Atomic City: Life Among the Decadent and the Depraved of Chornobyl, is about illegal trips to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.[27]

- The Chernobyl Poems of Lyubov Sirota by the professor of Washington University Paul Brians

- Lyubov Sirota’s novel "The Pripyat Syndrome"; Language: English, Publisher: Independently published (February 18, 2021), Paperback: 202 pages, ISBN 979-8710522875 – Lyubov Sirota (Author), Birgitta Ingemanson (Editor), Paul Brians (Editor), A. Yukhimenko (Illustrator), Natalia Ryumina (Translator)

- Much of the James Rollins' novel The Last Oracle takes place in Pripyat and around Chernobyl. The story revolves around a team of American "Killer Scientist" special agents who must stop a terrorist plot to unleash on the world the radiation of Lake Karachay, during the installation of the new sarcophagus over the Chernobyl nuclear power plant.

- The exclusion zone is the setting for Karl Schroeder's science fiction short story "The Dragon of Pripyat".

Music

[edit](Alphabetical by artist)

- The Ukrainian singer Alyosha recorded most of the video for her Eurovision 2010 entry, "Sweet People", in Pripyat.

- Ash, the rock band from Northern Ireland, has a song titled "Pripyat" included in their album A–Z Vol.1.

- The Italian Rapper Caparezza has a song titled "Come Pripyat" on his album Exuvia, released in 2021.[28]

- The song "Dead City" (Ukrainian: Мертве Місто) by the Ukrainian symphonic metal band DELIA is about Pripyat, and scenes from the music video were shot in the city. DELIA's vocalist, Anastasia Sverkunova, was born in Pripyat just before the Chernobyl disaster.[29]

- In 2006, musician Example featured Pripyat in his 18-minute documentary of the ghost town and in his promotional video for his track, "What We Made".

- German composer and pianist Hauschka included a piece titled "Pripyat" on his 2014 album Abandoned City (on which each track is titled after a different abandoned place.)

- The Scottish post-rock band Mogwai included a song titled "Pripyat" on their album Atomic (2016), which is a soundtrack to Mark Cousins' documentary Atomic, Living in Dread and Promise.

- The Belarusian post-punk band Molchat Doma released a music video for their song titled, "Waves" (Russian: Волны) as part of their album Etazhi. The music video was filmed in Pripyat through a series of varying drone shots; displaying famous landmarks of the abandoned city.[30]

- The Irish folk-rock singer Christy Moore included a song called "Farewell to Pripyat" on his album Voyage (1989), the song credited to Tim Dennehy.

- In 2014, for the twentieth anniversary of Pink Floyd's The Division Bell, a music video for the song "Marooned" was produced and released on the anniversary box set of the album. Aubrey Powell of Hipgnosis directed the video, filming some parts in Pripyat during the first week of April 2014.[31]

- Marillion guitarist Steve Rothery's first solo album is titled The Ghosts of Pripyat (2014).

- The Australian rapper Seth Sentry included the two-part song "Pripyat" in his album Strange New Past (2015).

- The English rock band Suede used the city to shoot their music video clip Life Is Golden, including takes of the Azure Swimming Pool, Pripyat amusement park, and Polissya hotel.

Television

[edit](Alphabetical by series)

- The 60 Minutes episode "Chernobyl: The Catastrophe That Never Ended" (early 2014) aired on CBS.[23][32]

- HBO's drama miniseries Chernobyl (2019) is based on the Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster. The scenes set in 1986 Pripyat were filmed in Vilnius, Lithuania.

- in the Chris Tarrant: Extreme Railways Season 5 episode "Extreme Nuclear Railway: A Journey Too Far?" (episode 22), Chris Tarrant visits Chernobyl on his journey through Ukraine.

- Discovery Science Channel's Mysteries of the Abandoned episode "Chernobyl's Deadly Secrets",[33] produced and hosted by Philip Grossman,[34] was filmed over a four-day period in Pripyat and the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, in 2017.

- The Animal Planet nature investigation series River Monsters conducted an extensive 2013 investigation within Pripyat, the exclusion zone, and the Chernobyl Power Plant in search of a radioactive mutated wels catfish.[35]

- A David Attenborough documentary depicts natural life in Pripyat.[36]

Video games

[edit]- Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare's (and its remaster's) single-player campaign includes levels "All Ghillied Up" and "One Shot, One Kill", which are set in Pripyat.[37]

- The S.T.A.L.K.E.R. franchise is set around the Chornobyl exclusion zone, and prominently features Pripyat in the series, namely in S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Call of Pripyat.

- SCUM, developed by the Croatian studio Gamepires, features a radiation area than includes a fictional city of "Krsko," which is an accurate reproduction of Pripyat, including points of interest.

- Chernobylite, developed by The Farm 51, allows players to explore the city and points of interest.[38]

Transport

[edit]

The city was served by Yaniv station on the Chernihiv–Ovruch railway. It was an important passenger hub of the line and was located between the southern suburb of Pripyat and Yaniv. An electric train terminus of Semikhody, built in 1988 and located in front of the nuclear plant, is currently the only operating station near Pripyat connecting it to Slavutych.[39]

Notable people

[edit]- Markiyan Kamysh (born 1988) writer, illegal Chernobyl explorer

- Vitali Klitschko (born 1971) politician, mayor of Kyiv and former professional boxer

- Wladimir Klitschko (born 1976) former professional boxer

- Alexander Sirota (born 1976) photographer, journalist and filmmaker

- Lyubov Sirota (born 1956) poet, writer, playwright, journalist and translator

Gallery

[edit]-

Pripyat in winter

-

Pripyat in winter

-

A gate in Pripyat city, 2000

-

Ferris wheel of the Pripyat amusement park

-

Pripyat city limit sign with a radiation dosimeter

-

Palace of Culture Energetik — artistic, cultural, entertainment and recreational activities center

-

The former football stadium of Pripyat

-

Abandoned football ground

-

Forest area near the city

-

Pripyat pier

-

Abandoned school

-

Pripyat after the disaster

-

Pripyat skyline

-

Pripyat bumper car floor

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /ˈpriːpjət, ˈprɪpjət/, PREE-pyət, PRIP-yət; Russian: Припять, IPA: [ˈprʲipʲɪtʲ] ⓘ.

- ^ Ukrainian: Припʼять, IPA: [ˈprɪpjɐtʲ] ⓘ.

References

[edit]- ^ "Elevation of Pripyat, Scotland Elevation Map, Topography, Contour". Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ "City Phone Codes". Archived from the original on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Pripyat: Short Introduction Archived 11 July 2012 at archive.today

- ^ "Chernobyl and Eastern Europe: My Journey to Chernobyl 6". Chernobylee.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ "Pripyat – City of Ghosts". chernobylwel.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ "History of the Pripyat city creation". chornobyl.in.ua. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Anastasia. "dirjournal.com". Info Blog. Archived from the original on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Hjelmgaard, Kim (17 April 2016). "Pillaged and peeling, radiation-ravaged Pripyat welcomes 'extreme' tourists". USA Today. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Gais, Hannah; Steinberg, Eugene (26 April 2016). "Chernobyl in Spring". Pacific Standard. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ LEE, PHOTOS BY ASSOCIATED PRESS, EDITED BY AMANDA (4 February 2020). "AP Gallery: Chernobyl town Pripyat celebrates 50th anniversary". Columbia Missourian. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roth, Andrew (13 April 2020). "Ukraine: wildfires draw dangerously close to Chernobyl site". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Fighting breaks out near Chernobyl, says Ukrainian president". The Independent. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Russia Hands Control of Chernobyl Back to Ukraine, Officials Say". Wall Street Journal. 31 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Ukrainian flag was raised at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant Archived 2 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrainska Pravda (2 April 2022)

- ^ Kyiv region: Ukrainian military take control of Pripyat and section of border Archived 25 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrainska Pravda (3 April 2022)

- ^ "Ukrainian forces regain control of Pripyat, the ghost town near the Chernobyl nuclear plant". 3 April 2022. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Припять в цифрах Archived 13 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine ("Pripyat in Numbers"), a page from Pripyat website

- ^ "Radiation levels". The Chernobyl Gallery. 24 October 2013. Archived from the original on 29 September 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Mindat.org https://www.mindat.org/loc-271143.html Archived 6 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Prypiat climate". Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Chernobyl Diaries at IMDb

- ^ DJI (14 August 2015), DJI Stories – The Lost City of Chernobyl, archived from the original on 25 August 2015, retrieved 24 March 2016

- ^ a b "Witness a Drone's Eye View of Chernobyl's Urban Decay". The Creators Project. 24 November 2014. Archived from the original on 26 November 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "من فوق.. كيف يبدو ما بقي من تشيرنوبل بعد 30 عاما من الكارثة النووية؟". CNN Arabic. December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (4 August 2016). "The story behind 'The Girl With All The Gifts'". Screen International. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ White Horse at IMDb

- ^ "Stalking the Atomic City by Markiyan Kamysh". Penguin Random House Canada. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ "Exuvia". Record Store Day. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "DELIA". Archived from the original on 11 December 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "Molchat Doma - Volny (Official Lyrics Video) молчат дома - волны". YouTube. 5 September 2020. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Johns, Matt (19 May 2014). "Pink Floyd release new Marooned video...and TDB20 countdown!". Brain-damage.co.uk. Retrieved 24 September 2025.

- ^ "من فوق.. كيف يبدو ما بقي من تشيرنوبل بعد 30 عاما من الكارثة النووية؟". CNN Arabic. December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "Philip Grossman - Mysteries of the Abandoned Cast". Science. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ "Philip Ethan Grossman". IMDb. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Atomic Assassin". Animal Planet. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ "Our Planet" Forests (TV Episode 2019) ⭐ 9.1 | Documentary. Retrieved 31 May 2025 – via m.imdb.com.

- ^ Burford, GB (23 October 2014). "Why Modern Warfare's 'All Ghillied Up' Is One Of Gaming's Best Levels". Kotaku. Univision Communications. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ Natividad, Sid (29 August 2021). "5 Things We Loved About Chernobylite (& 5 Things We Don't)". gamerant.com. Valnet. Retrieved 30 August 2025.

- ^ "Radioactive Railroad". Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

External links

[edit]- Pripyat-Info – Informational Portal: «PRIPYAT :: EXCLUSION ZONE»

- Pripyat.com – Site created by former residents

- 25 years of satellite imagery over Chernobyl Pripyat map

- pripyatpanorama.com – Pripyat in Panoramas Project

- exploringthezone.com Archived 12 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine – 5-year project documenting the Pripyat and Chernobyl Zone

- Pripyat-city.ru Archived 17 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine – Blog related to Pripyat

- ChernobylGallery.com – Photographs of Pripyat and Chernobyl

- Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, Pripyat 2018 on YouTube – 2018 Footage of Pripyat and Chernobyl

Pripyat

View on GrokipediaFounding and Early Development

Establishment and Purpose

Pripyat was established on February 4, 1970, by the Soviet government in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic as a purpose-built closed city to support the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant under construction approximately 3 kilometers away.[7][8] The site was selected near the Pripyat River in Kyiv Oblast for its relative isolation and logistical advantages, with initial construction focusing on worker housing amid the broader Soviet push for nuclear energy expansion during the Ninth Five-Year Plan (1971–1975).[8] As the ninth "atomograd"—a Soviet designation for secretive cities orbiting atomic facilities—Pripyat's primary purpose was to provide modern accommodations, infrastructure, and amenities exclusively for plant employees, their families, and associated scientific personnel, ensuring operational efficiency and secrecy.[7] Unlike open cities, it operated under restricted access protocols typical of military-industrial complexes, with residents selected based on security clearances and proximity to the power station's projected workforce needs, which were anticipated to exceed 10,000 by full operational capacity.[9] The plant itself began construction in 1970, with its first RBMK-1000 reactor grid-connected in December 1977, underscoring the city's foundational role in sustaining round-the-clock nuclear operations.[2] Planning emphasized self-sufficiency and ideological symbolism, incorporating communal facilities like schools, hospitals, and cultural centers to foster a model socialist community, reflective of Brezhnev-era priorities on technological prestige over environmental or safety transparency.[8] Initial population targets aimed for rapid growth to 50,000 by the mid-1980s, prioritizing young, educated workers to align with the Soviet atomic program's demands for specialized labor in reactor maintenance, fuel handling, and research.[10]Construction and Urban Planning

Pripyat was established on February 4, 1970, as a planned satellite city to house workers and their families for the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, constructed concurrently from 1970 to 1977.[7][11] Initial construction began with dormitories and canteens in 1971, followed by the first apartment buildings and a school in 1972, when the settlement received urban-type status; it was granted city status in 1979.[7] The city was designed to accommodate 75,000 to 85,000 residents, featuring over 13,000 apartments across 160 prefabricated blocks, nearly 100 schools, a hospital, and a central administrative core.[7][11] Urban planning followed Soviet modernist principles, organized into five microdistricts radiating from a central administrative and cultural hub, with wide streets, open green spaces, and a mix of standard panel and high-rise buildings.[11][7] The layout incorporated a "triangular" construction concept developed by a team of Moscow architects under Nikolai Ostozhenko's leadership, emphasizing efficient land use and functional zoning for an atomgrad— a specialized nuclear worker settlement.[7] Chief architect Gennady Ivanovich Oleshko oversaw the design, which included planned expansions by 1988 such as two shopping centers, a two-screen cinema, sports complexes, and a 52-meter television tower.[7] Construction utilized prefabricated elements typical of Soviet-era rapid urbanization, prioritizing communal amenities and worker efficiency over individual variation.[11]Pre-Disaster Society and Economy

Population Growth and Demographics

Pripyat was established on February 4, 1970, as a purpose-built settlement for workers at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, initially with no resident population as construction began from undeveloped marshland.[12] By 1979, when it received official city status, the population had expanded through influxes of nuclear plant employees and support staff drawn by state incentives, reaching several thousand residents amid rapid housing development.[2] The city's population continued to surge in the 1980s, driven by the commissioning of additional reactor units and associated job opportunities, growing to approximately 47,000 by 1985 and peaking at around 49,400 on the eve of the Chernobyl disaster in April 1986.[13] [12] This growth reflected Soviet priorities for atomgrads—specialized nuclear towns—originally planned to accommodate up to 75,000 inhabitants, though actual expansion exceeded initial projections for a workforce of about 17,000 due to family relocations and births.[13] Demographically, Pripyat featured a youthful profile typical of new Soviet industrial cities, with an average resident age of 26 years in 1986 and over 15,000 children under 18 comprising roughly one-third of the populace.[14] [15] The population was multi-ethnic, drawing from more than 25 nationalities across the Soviet Union, including substantial numbers of Ukrainians, Russians, and Belarusians recruited for skilled labor in engineering, construction, and plant operations, alongside smaller contingents from republics like Kazakhstan.[15] This composition mirrored broader Soviet migration patterns to remote industrial sites, prioritizing technical expertise over local ethnic homogeneity, though precise census breakdowns remain limited in declassified records.[2]Daily Life and Amenities

Pripyat's residents, primarily Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant workers and their families, experienced a daily routine centered on industrial employment, with many adults working shift schedules at the facility. The city's young demographic, averaging 26 years of age in 1986 and comprising residents from over 30 Soviet nationalities, featured a notable baby boom, leading to mornings filled with young mothers pushing baby carriages along flower-lined streets amid pine groves. Children, making up over one-third of the approximately 50,000 population, attended local kindergartens and schools, while leisure pursuits included sunbathing, fishing, and swimming in the Pripyat River or the power plant's expansive cooling pond, which sustained a year-round fishery.[16][17] The city boasted amenities exceeding typical Soviet urban standards, designed to attract skilled nuclear personnel, including five schools, multiple kindergartens such as Goldfish and Little Sunshine, and a library planned to hold 500,000 volumes. Healthcare facilities centered on Medical-Sanitary Center No. 126, equipped with more than 400 beds, 1,200 staff, and a large maternity ward to serve the growing families. Commercial options encompassed grocery stores stocking fresh produce, sausage, and beer, alongside the Raduga department store offering goods scarce in larger cities like Kyiv or Minsk, supported by 25 shops overall.[16][17][15] Cultural and recreational infrastructure included the Palace of Culture Energetik for artistic events, parades, and Soviet holiday celebrations; a cinema; sports facilities such as a stadium, swimming pool, and multiple sports halls; cafes; and playgrounds in residential areas. Transportation amenities featured a daily Rakete hydrofoil to Kyiv, covering the distance in about two hours, while an amusement park with a Ferris wheel neared completion for a May 1, 1986, opening but saw no public use. These provisions reflected Pripyat's role as a model "atomgrad," prioritizing worker retention through elevated living conditions.[17][15][16]

The Chernobyl Nuclear Accident

Causes and Sequence of Events

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant accident at Unit 4 stemmed primarily from inherent design deficiencies in the Soviet RBMK-1000 reactor, compounded by severe operational violations during a low-power safety test on April 25–26, 1986.[18][2] The RBMK's positive void coefficient meant that steam voids in the coolant increased reactivity rather than decreasing it, creating instability especially at low power levels and high fuel burn-up, as voids displaced water without sufficient negative feedback.[18] Additionally, the control rods featured graphite displacers that, upon insertion, initially displaced neutron-absorbing water, injecting positive reactivity and exacerbating power surges during emergency shutdowns.[18][2] These flaws violated basic nuclear safety principles, yet the design lacked a robust containment structure, allowing unchecked release of radioactive materials.[2] Operator actions critically amplified these vulnerabilities, as personnel under inadequate training and supervision disabled multiple safety systems, including the emergency core cooling system, and operated with an operational reactivity margin (ORM) of only 6–8 rods—far below the required minimum of 15–30 rods—rendering the reactor highly sensitive to perturbations.[18][19] The test aimed to simulate a turbine rundown for emergency power supply but was postponed repeatedly, leading to xenon-135 poisoning that further depressed reactivity; attempts to compensate by withdrawing rods and reducing coolant flow pushed the core into an unforgiving state.[2] Initial Soviet analyses (INSAG-1) attributed the disaster mainly to human error, reflecting a tendency to deflect blame from systemic design and regulatory failures, but subsequent IAEA investigations (INSAG-7) established design shortcomings as the root cause, with operator errors serving as the precipitating trigger in an inherently unsafe configuration.[18] The sequence unfolded as follows: On April 25, 1986, at 01:05 local time, power reduction began for the test, halting at 1,600 MW thermal (MWt) around 03:47 due to grid demands, with ORM dropping to 13 rods.[19] Reduction resumed at 23:10, reaching a critically low 30 MWt by 00:28 on April 26 due to control transfer issues and xenon buildup, stabilizing unstably at 200 MWt by 01:00 with ORM at 8 rods.[19][18] At 01:23:04, the test commenced with turbine feed valve closure, reducing coolant flow by 10–15% to 56,000 m³/h and initiating boiling that boosted voids and reactivity via the positive coefficient.[19][18] Power began rising uncontrollably; at 01:23:40, operators pressed the AZ-5 emergency button, inserting 211 control rods over 18 seconds, but the graphite tips caused an initial reactivity spike, shifting neutron flux to the core bottom and multiplying power 30-fold within seconds to 3.5–80 times nominal levels, rupturing fuel channels.[18][19] By 01:23:43, the surge triggered steam buildup, culminating in a primary steam explosion around 01:24 that destroyed the core and pressure vessel, followed by a secondary explosion—likely from hydrogen generated by zirconium-water reactions or further steam pressure—that breached the reactor hall and ignited the graphite moderator.[18][2] This released approximately 5% of the core inventory immediately, with the graphite fire sustaining airborne dispersal for days.[2]Immediate Aftermath and Soviet Response

The explosion at Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant's Unit 4 occurred at 01:23:40 local time on 26 April 1986 during a low-power safety test, resulting in a steam explosion followed by a hydrogen blast that destroyed the reactor core, blew off the 1000-tonne roof, and ignited a graphite fire, releasing approximately 5200 PBq of radioactive isotopes into the atmosphere. Two plant workers died instantly from the physical trauma of the explosions. Operating staff initially attempted to mitigate the damage by injecting water into the core for cooling, but this effort was halted after about half a day due to risks of flooding the basement with contaminated water. Firefighting units from Pripyat and nearby Chernobyl arrived within ten minutes of the initial alert and spent hours combating the intense graphite fires on the reactor roof and adjacent turbine hall, extinguishing most flames by around 05:00, though embers persisted for days; responders lacked radiation detection equipment or protective gear suited to the hazard, as the full scale of the radioactive release was not immediately recognized.[2][20] The absence of adequate initial safeguards exposed first responders and plant personnel to extreme radiation doses, with firefighters and workers on the roof receiving up to 20 Sv (20,000 mGy), far exceeding lethal thresholds; this led to acute radiation syndrome (ARS) in 134 cases among emergency workers and operators, characterized by symptoms including vomiting, diarrhea, and skin burns appearing within hours. By the end of July 1986, 28 of these individuals—primarily firefighters and shift staff—had succumbed to ARS-related multi-organ failure, while two additional early deaths were attributed to blast injuries and one to cardiac arrest amid the chaos. Helicopter reconnaissance began later on 26 April to assess the site, revealing open-core exposure and high radiation fields, prompting the deployment of boron, sand, clay, and lead drops totaling 5000 tonnes over the following nine days to suppress fission, though this operation itself contributed to further contamination via resuspended particles. Medical facilities in Pripyat treated initial casualties with limited understanding of radiation poisoning, transferring severe cases to Moscow's Clinic No. 6 by helicopter, where experimental treatments like bone marrow transplants were attempted but yielded mixed results due to the unprecedented exposure levels.[2][21][20] Soviet authorities received reports of the incident within hours, with the plant director notifying Kiev regional officials by mid-morning on 26 April, but initial assessments underestimated the catastrophe's severity, citing a manageable fire rather than a core meltdown; a government commission under Boris Shcherbina was dispatched from Moscow that afternoon, arriving by evening to oversee operations, yet directives prioritized containing the fire and emissions over immediate public alerts. Despite detecting rising radiation in Pripyat—reaching 300 μSv/h by afternoon, comparable to a chest X-ray per minute—officials assured residents of safety, allowing normal activities including children's outdoor play to continue into 27 April, a decision later attributed to fears of panic and logistical unpreparedness. The Politburo, informed by 26 April, imposed information restrictions, delaying international notification until after Sweden's independent detection of fallout on 28 April prompted inquiries; the first TASS agency bulletin that evening acknowledged "an accident" at Chernobyl with two deaths but omitted details of the explosion, radiation plume, or evacuation needs, framing it as under control to align with state narratives of technological reliability. This opacity extended to suppressing dosimeter readings and worker testimonies, reflecting ingrained Soviet practices of crisis minimization, which exacerbated exposures before broader mobilization of approximately 600,000 "liquidators" commenced in subsequent weeks. Mikhail Gorbachev's first public address on the disaster occurred only on 14 May, by which time the scale of contamination was undeniable, underscoring the regime's initial prioritization of secrecy over transparency.[2][21][20]Evacuation of Pripyat

The evacuation of Pripyat commenced on April 27, 1986, at 14:00 local time, approximately 36 hours after the Chernobyl reactor explosion on April 26 at 01:23.[22][23] Soviet authorities issued the order following measurements indicating rising radiation levels in the city, which housed approximately 49,000 residents primarily employed at the nearby nuclear plant.[22][21] The decision came after initial hesitation, as officials had downplayed the incident's severity publicly and prioritized firefighting and containment efforts over immediate mass relocation. Residents received announcements via loudspeakers and were instructed to assemble at designated points within two hours, taking only essential documents, medications, and clothing, with assurances that the displacement would last no more than three days.[24] Over 1,200 buses, mobilized from Kyiv and surrounding regions, transported the population in an operation lasting about 3.5 hours, though logistical delays extended the process into the evening.[24] Pripyat's 43,000 to 49,000 inhabitants—many of whom were families of plant workers—were directed to temporary settlements outside the emerging exclusion zone, leaving behind pets, furniture, and personal belongings due to the urgency.[22][24] This initial phase marked the first major relocation, with the 10-kilometer exclusion zone formalized around the plant, though contamination patterns later necessitated its expansion to 30 kilometers.[2] The delay in evacuating Pripyat, despite detectable fallout plumes reaching the city by the morning of April 26, stemmed from Soviet protocols emphasizing operational continuity at the plant and underestimation of airborne iodine-131 and cesium-137 dispersal.[25] Evacuees incurred average radiation doses of around 10-30 millisieverts during transit and preparation, primarily from external gamma exposure and ground deposition, though this was lower than doses for on-site responders due to the timing.[21] International assessments, including those by UNSCEAR, note that the evacuation mitigated higher projected exposures from prolonged residence, as Pripyat's proximity (3 kilometers from the plant) placed it under severe initial plume paths.[21] Subsequent relocations in 1986 expanded to 115,000-116,000 individuals from wider contaminated areas, revealing the operation's scale as a response to uneven radionuclide deposition rather than uniform zoning.[21][26] Pripyat's evacuation exemplified early Soviet crisis management flaws, including restricted information flow that hindered timely dosimetric monitoring and public preparedness, as documented in declassified protocols and post-accident inquiries.[27] While no immediate fatalities occurred among evacuees from acute radiation syndrome, long-term health monitoring has linked cohort exposures to elevated thyroid cancer risks from iodine uptake prior to relocation.[28] The city's abandonment preserved its infrastructure in a state of suspended decay, with return prohibited indefinitely due to persistent cesium contamination in soil and structures.[2]Exclusion Zone and Post-Evacuation History

Establishment of the Zone

The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone was formally established on 2 May 1986 by a Soviet government commission chaired by Premier Nikolai Ryzhkov, in response to the ongoing radioactive contamination from the April 26 nuclear accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. This decree defined a restricted area with an approximate 30-kilometer radius around the plant, initially encompassing roughly 2,600 square kilometers of Ukrainian SSR territory, to limit human exposure to elevated radiation levels from fallout including cesium-137, iodine-131, and strontium-90. The zone's boundaries were delineated based on aerial and ground radiation surveys conducted by Soviet military and scientific teams, which revealed hotspots exceeding permissible exposure limits by factors of hundreds or thousands in proximity to the reactor.[29][30] The newly created zone was subdivided into three concentric subzones to prioritize evacuation and control measures according to contamination gradients: an inner 10-kilometer radius for immediate and total mandatory evacuation (already partially executed for Pripyat and nearby settlements); a middle band for staged relocation of remaining residents; and an outer supervised area permitting limited habitation under strict monitoring. This tiered structure reflected pragmatic assessments of decay rates and deposition patterns, with the inner zone designated for unrestricted access bans except for cleanup operations, while outer areas allowed selective agricultural and residential activity pending decontamination. Approximately 115,000 people had been evacuated from the broader 30-kilometer perimeter by early May, though initial Soviet reluctance to acknowledge the disaster's severity—evident in delayed public warnings—had confined early restrictions to a provisional 10-kilometer perimeter established around April 27.[31][2] Enforcement of the zone involved deployment of Internal Troops of the Soviet Ministry of Defense to seal perimeters, install checkpoints, and conduct patrols, supplemented by KGB oversight to suppress information leakage amid the government's initial cover-up efforts. Legal authority stemmed from Council of Ministers resolutions invoking emergency powers under Article 71 of the USSR Constitution, framing the zone as a temporary "alienation" area for liquidation (cleanup) works projected to last 2–5 years, though empirical data on long-term isotope persistence—such as cesium-137's 30-year half-life—later invalidated such optimism. The establishment prioritized causal containment of exposure risks over economic considerations, resettling evacuees to new sites like Slavutych, but systemic opacity in Soviet reporting understated plume dispersion, leading to uneven zone adjustments in subsequent months.[20][2]Soviet Liquidation Efforts and Cover-Up

The Soviet response to the Chernobyl disaster involved mobilizing approximately 600,000 personnel, termed liquidators, primarily military reservists, miners, and civilian workers, to contain the reactor damage and decontaminate affected areas including Pripyat from 1986 through 1991.[32] [2] Initial efforts focused on extinguishing the Unit 4 graphite fire, which raged until May 10, 1986, through helicopter drops of over 5,000 tons of sand, boron, dolomite, and lead—totaling more than 500 flights daily at peak—to smother flames and limit further radionuclide release.[2] By late May 1986, around 20,000 liquidators were on-site, with tasks expanding to pumping out contaminated water from the reactor basement to avert a steam explosion and constructing a concrete "sarcophagus" enclosure over the ruined unit, completed in November 1986 despite radiation levels exceeding 300 roentgens per hour in some areas.[2] [33] Decontamination operations in Pripyat and the surrounding 30-kilometer exclusion zone entailed stripping and burying contaminated topsoil—estimated at millions of cubic meters—hosing buildings and roads with high-pressure water mixed with decontamination agents, and demolishing or sealing heavily irradiated structures.[2] Soviet reports claimed Pripyat was 95% decontaminated by late 1986, yet persistent hotspots and groundwater contamination rendered resettlement unfeasible, leading to the city's indefinite abandonment.[34] Liquidators faced inadequate protective gear and rotating shifts limited to 40-120 seconds in high-radiation zones, resulting in acute exposures; some 20,000 received doses around 250 millisieverts, with outliers nearing 500 millisieverts, far above safe annual limits.[2] These efforts, while reducing immediate risks, prioritized rapid containment over long-term safety, with miners tunneling beneath the reactor to install a protective slab completed by October 1986.[33] Parallel to these operations, Soviet authorities orchestrated a cover-up to minimize perceived incompetence and avoid international scrutiny, delaying public acknowledgment of the accident's scale despite radiation detections in Sweden on April 28, 1986.[35] Domestic media silence persisted until May 14, 1986, when General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev addressed the nation, framing the event as manageable while omitting key details like the reactor's design flaws and explosion cause; this lag hindered timely evacuations beyond Pripyat and protective measures for over 100,000 exposed residents in Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia.[35] [36] Declassified KGB and Politburo documents reveal systematic suppression of data on liquidator casualties and health effects, with initial death tolls underreported—official figures cited 31 immediate fatalities, excluding delayed radiation illnesses—and disinformation campaigns assuring minimal long-term harm despite evidence of thyroid cancers emerging by 1987.[32] Pre-accident cover-ups of Chernobyl's safety violations, including three prior near-misses between 1981 and 1985, compounded the response failures by fostering a culture of secrecy that impeded effective planning.[37] This opacity extended to liquidators, many conscripted without informed consent and later denied full benefits, as state records minimized exposures to sustain morale and narrative control.[38]Post-Soviet Administration and Recent Events

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, encompassing Pripyat, transitioned to Ukrainian administration, with the Ukrainian government establishing oversight mechanisms for the restricted area spanning approximately 2,600 square kilometers.[2] The State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management (DAZVR), operating under the Ministry of Communities and Territories Development, assumed primary responsibility for zone governance, including radiation monitoring, infrastructure maintenance, and radioactive waste handling, with activities focused on long-term safety and environmental protection.[39] This agency coordinates with international bodies like the IAEA for technical support, emphasizing empirical radiation data over speculative risks.[20] In 2016, Ukraine designated portions of the exclusion zone as the Chernobyl Radiation and Environmental Biosphere Reserve to promote scientific research and biodiversity preservation, recognizing ecological recovery driven by reduced human activity rather than narrative-driven conservation claims.[2] Controlled tourism to Pripyat and surrounding sites emerged in the early 2000s, regulated by DAZVR permits, attracting around 150,000 visitors annually by 2019 through licensed operators enforcing dosimetric controls and restricted paths to minimize exposure, though unofficial entries persisted via poachers and self-styled guides in the 1990s.[40] Tourism halted after the 2022 invasion, with post-war plans aiming to leverage the site's historical significance for economic development while maintaining safety protocols.[40] The Russian military occupation of the Chernobyl site, including Pripyat, from February 24 to March 31, 2022, involved over 300 personnel in the zone at occupation's start, with forces using the area as a staging ground, leading to protocol violations such as off-path vehicle movement and soil disturbance.[41] Gamma dose rates spiked significantly during this period, reaching up to 9.46 microsieverts per hour near Pripyat's monitoring posts—over 10 times pre-invasion levels—but scientific analysis attributed increases to meteorological factors like wind and snowmelt rather than vehicular resuspension of contaminated soil.[42] Post-withdrawal, Ukrainian forces cleared the zone, addressing damages estimated in tens of millions from equipment disruption and initiating de-mining operations amid reports of unexploded ordnance; radiation levels normalized by April 2022.[43] In 2024, DAZVR appointed a new head to enhance management amid ongoing war-related challenges, including a reported Russian drone strike causing structural damage to site facilities.[44] By 2025, discussions in Ukraine's Verkhovna Rada focused on zone potential for controlled access and dosimetric certification procedures to support recovery efforts.[45]Physical Infrastructure and Layout

Architectural Features

Pripyat's architecture exemplified Soviet modernism, characterized by utilitarian prefabricated concrete panel buildings designed for rapid construction and functional efficiency.[46] The city featured standardized residential blocks, primarily 5- to 9-story high-rises built using series like 111-60-12, which allowed for mass production of apartments to house nuclear plant workers.[47] These structures, constructed from precast concrete panels, prioritized communal living over individual aesthetics, aligning with late-Soviet housing policies that emphasized planned economy and limited design variation.[48] The urban layout adhered to the "triangular construction" principle developed by Moscow architects under Nikolai Ostretsov, organizing the city into five microdistricts with 149 multistoried buildings encompassing approximately 13,000 apartments and 52,000 square meters of living space.[7] This zoning approach integrated residential zones with green spaces, schools, and service facilities within walking distance, reflecting Soviet ideals of self-contained neighborhoods to foster social cohesion.[11] Wide avenues and centralized administrative cores further embodied the era's emphasis on monumental scale and ideological symbolism, positioning Pripyat as a model "atomgrad" for atomic energy workers.[11] Public and civic buildings incorporated similar modernist elements, with exposed concrete facades and functional geometries, as seen in structures like the Palace of Culture and hotels designed for communal activities.[49] Construction, initiated in 1970, utilized industrial methods to achieve high density while incorporating planned expansions for up to 50,000 residents, though the 1986 disaster halted further development.[8]

Key Public Facilities

Pripyat's key public facilities were constructed to support a planned population of up to 75,000 residents, primarily Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant workers and their families, emphasizing Soviet ideals of communal welfare and recreation. These included administrative centers, healthcare providers, educational institutions, and cultural venues, many completed by the early 1980s as the city reached its peak of around 49,000 inhabitants in 1986.[7][8] The Palace of Culture Energetik, built in the early 1970s in the city center, functioned as the hub for artistic, cultural, entertainment, and recreational activities, reflecting Pripyat's status as a model "atomgrad" town. It featured a cinema, theater and concert hall, library, gymnasium, swimming pool, boxing and wrestling ring, dancing halls, and meeting spaces for community events.[50][51] Healthcare infrastructure centered on Pripyat Hospital (also known as Hospital No. 126), a multi-story facility equipped for general medical care, including emergency services for the nuclear workforce; it treated initial victims of the 1986 accident before operations ceased.[7][52] Educational facilities comprised 15 schools and kindergartens, alongside specialized institutions like a music school adjacent to the Palace of Culture, designed to educate children of plant employees up to secondary level.[53][54] The Polissya Hotel, a seven-story structure in the central administrative district, accommodated visitors, plant officials, and transient workers, with amenities including a restaurant and conference spaces near the city executive committee and party headquarters.[8] Sports and leisure options included the Avanhard Stadium for team athletics, 10 gyms across the city, and the Azure Swimming Pool complex, operational by 1985 for public aquatic recreation.[53][55]Transportation Networks

Pripyat's transportation infrastructure was designed to support a population of up to 50,000 residents and workers at the adjacent Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, featuring a central bus station as the primary intercity hub located just off the main access road from Kyiv, approximately 150 kilometers away. The station facilitated 14 bus routes connecting to regional towns, villages, and the capital, with 167 urban buses operating intra-city services across its microdistricts.[56][15][55] Rail access was provided via the nearby Yaniv railway station on the Chernihiv–Ovruch line, established in 1925 and situated about 2 kilometers south of Pripyat's southern boundary in the village of Yaniv. This station handled both passenger and freight traffic essential for supplying the power plant, serving as a key node before the 1986 disaster halted operations.[57][58][59] A river port on the Pripyat River complemented road and rail, enabling barge transport for construction materials and goods during the city's development in the 1970s. Internal road networks followed a grid layout with wide avenues linking residential areas, public facilities, and the power plant, including dedicated parking for 400 vehicles at the plant site to accommodate shift workers' private cars.[15][7]Environmental Conditions

Climate Profile

Pripyat lies within the humid continental climate zone (Köppen Dfb), marked by distinct seasons with cold winters influenced by Siberian air masses and warmer summers moderated by Atlantic influences.[60] Winters typically feature sub-zero temperatures, frequent snowfall, and occasional thaws, while summers bring higher humidity and thunderstorm activity. Annual precipitation averages around 610 mm, distributed relatively evenly but peaking in the summer months due to convective rainfall.[61] The coldest month is January, with a mean temperature of -3.4 °C (25.9 °F) and frequent lows below -10 °C (-14 °F), leading to snow cover persisting for 90-120 days annually. July, the warmest month, averages 20.1 °C (68.2 °F), with highs occasionally exceeding 30 °C (86 °F) during heatwaves. Extreme temperatures have ranged from -36 °C (-33 °F) in winter to 39 °C (102 °F) in summer, reflecting the region's vulnerability to continental extremes.[61][62] Precipitation is lowest in late winter and early spring (35-40 mm monthly), rising to 70-80 mm in June and July, supporting deciduous forests and wetlands in the surrounding Polesian Lowland. Fog and overcast skies are common in autumn, contributing to moderate winds averaging 3-4 m/s year-round, though gusts can intensify during frontal passages.[61] These patterns have remained stable historically, with no significant long-term shifts attributable to the 1986 Chernobyl incident, as climate drivers stem from broader synoptic patterns rather than localized radiation effects.[63]Post-Accident Ecological Shifts

Following the Chernobyl nuclear accident on April 26, 1986, the immediate ecological impacts in the surrounding Pripyat area included acute radiation-induced mortality, particularly in the nearby Red Forest, where high doses exceeding 10 Gy caused mass die-off of Scots pine trees, turning their needles reddish-brown due to cellular damage and necrosis. This event affected approximately 4-6 square kilometers of forest, with soil contamination levels reaching up to 10^5 kBq/m² for cesium-137 in hotspots, leading to temporary reductions in microbial activity and invertebrate populations. Fauna exhibited direct effects such as increased mortality in small mammals and birds exposed to initial fallout, though heterogeneous deposition patterns resulted in patchy rather than uniform devastation across the exclusion zone.[5][64] Over subsequent decades, the absence of human activity facilitated significant ecological recovery, with forest cover in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone expanding from 41% in 1986 to 59% by 2020, driven by natural succession, reduced logging, and afforestation on abandoned agricultural lands. The Red Forest itself has undergone partial regeneration, with understory vegetation and some deciduous trees recolonizing the area, contributing to an overall increase in biodiversity despite persistent contamination. Plant communities have shown resilience, with populations of many species surpassing pre-accident levels, attributed to rapid decay of short-lived radionuclides—reducing initial contamination by over 95% within the first month—and adaptive mechanisms in surviving flora, though chronic exposure continues to impair photosynthesis and growth rates in radiosensitive species like pines.[65][66][67] Wildlife abundance has markedly increased, with ungulate populations such as elk, roe deer, and wild boar expanding rapidly from 1987 to 1996 due to unrestricted habitat access and cessation of hunting, leading to densities in some areas exceeding those in comparable undisturbed regions. Avian and mammalian diversity has similarly risen, with over 200 bird species and large carnivores like wolves and lynx establishing viable populations, underscoring the zone's transformation into a de facto wildlife refuge where human exclusion outweighs residual radiation effects. However, current low-level chronic exposure—typically 0.1-10 mGy/day in less contaminated sectors—correlates with subtle sublethal impacts, including reduced reproductive success in birds and smaller brain sizes in some passerines, though soil biota like nematodes and earthworms show no direct dose-dependent declines, suggesting thresholds below which radiation does not dominate ecological dynamics.[67][68][69] These shifts highlight a net positive for biodiversity from depopulation, as evidenced by camera trap surveys and population modeling, countering early narratives of a sterile wasteland; yet, variability in findings across studies reflects challenges in disentangling radiation from confounding factors like habitat alteration, with peer-reviewed radioecological research emphasizing site-specific heterogeneity over generalized catastrophe. Forest fires, recurrent in the dry understory, periodically remobilize radionuclides but have not precluded long-term vegetation rebound or caused transboundary escalation.[2][70][71]Radiation Exposure and Health Realities

Measured Radiation Levels

Immediately following the Chernobyl nuclear accident on April 26, 1986, ambient gamma dose rates in Pripyat, located approximately 3 km from the exploded reactor, rose rapidly due to the deposition of radioactive fallout, including isotopes such as iodine-131, cesium-137, and strontium-90. Measurements taken shortly before evacuation (initiated around 36 hours post-explosion) indicated outdoor dose rates in the city ranging from approximately 2 to 20 μSv/h in less affected areas, with higher localized readings near contaminated surfaces; indoor rates were lower due to shielding, contributing to an estimated average external effective dose of about 17 mSv for evacuees over their brief remaining exposure period.[72][73] Over subsequent decades, dose rates declined primarily through radioactive decay (e.g., short-lived isotopes like xenon-133 decayed within days, while cesium-137 with a 30-year half-life persists) and partial decontamination efforts, such as topsoil removal in select zones. By the early 1990s, average external dose rates across the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ), including Pripyat, had fallen to 5–15 μSv/h in many urban areas, as documented in international assessments; air radioactivity in Pripyat peaked transiently at 300 Bq/m³ but normalized with precipitation washout.[74][3] As of the 2010s and into the 2020s, continuous monitoring by Ukrainian authorities and international bodies like the IAEA reveals that Pripyat's current external gamma dose rates typically range from 0.2 to 5 μSv/h in open, decontaminated streets and buildings—comparable to or slightly above global natural background levels of 0.1–0.3 μSv/h—but can exceed 20 μSv/h in hotspots such as undisturbed soil, forested edges, or legacy contaminated structures like the cemetery (e.g., 21.88 μSv/h recorded).[75][76] These translate to projected annual doses of 1–5 mSv for hypothetical continuous occupants in central Pripyat, below occupational limits but elevated versus uncontaminated baselines.[2]| Location in Pripyat/CEZ | Typical Dose Rate (μSv/h) | Measurement Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| City center streets | 0.5–2 | 2010s–2020s | Post-decay average; varies with weather and vegetation.[5] |

| Cemetery or hotspots | 10–25 | Recent (post-2010) | Localized cesium-137 accumulation in soil/graves.[75] |

| Near reactor (extreme) | 10,000+ | 1986 initial | Fatal in minutes unprotected; now mitigated.[21] |

| Background (global avg.) | 0.1–0.3 | Ongoing | For comparison; Pripyat lows approach this.[77] |

Direct and Long-Term Health Effects

The direct health effects of the Chernobyl disaster were confined to highly exposed individuals, primarily plant operators, firefighters, and early responders, who suffered acute radiation syndrome (ARS) from doses often exceeding 6 Gy. Among 134 confirmed ARS cases, 28 fatalities occurred within the first four months, mainly from multi-organ failure and infections secondary to radiation-induced immunosuppression.[79] [2] Pripyat residents, numbering about 49,000 at the time, avoided ARS due to their evacuation on April 27, 1986—less than 36 hours after the April 26 explosion—with collective effective doses estimated at 10-50 mSv, insufficient to cause acute symptoms.[2] [72] Long-term health outcomes have centered on thyroid cancer, driven by iodine-131 inhalation and ingestion in the initial fallout plume, particularly affecting children and adolescents in contaminated regions including northern Ukraine. By 2015, over 19,000 thyroid cancer cases were documented among those under 18 at the time of exposure across Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine, with roughly one-quarter causally linked to Chernobyl radiation based on dose-response modeling.[80] [81] Pripyat evacuees, as part of the proximate Ukrainian cohort, contributed to this trend, though their lower average exposures (external doses around 17 mSv) limited incidence compared to more contaminated Belarusian areas; most cases proved treatable with surgery and iodine therapy, yielding over 95% five-year survival rates.[82] [72] Epidemiological assessments by UNSCEAR and others reveal no detectable radiation-attributable increases in overall cancer incidence, leukemia (beyond early liquidator cases), or non-thyroid solid tumors among evacuees or the broader population, even decades post-accident.[21] [2] Liquidators—totaling over 600,000, including some Pripyat workers—exhibited elevated all-cause mortality, with standardized rates 7-20% above norms by the 1990s-2000s, but these excesses align more closely with cardiovascular disease, suicide, and alcoholism than ionizing radiation, as low-dose effects (<200 mSv) fall below linear no-threshold model thresholds for broad carcinogenic impact.[83] [84] No verified surges in birth defects, infertility, or heritable genetic disorders have materialized, contradicting early fears; projections of 4,000 excess radiation deaths (mostly hypothetical future cancers) from a 2005 WHO-IAEA analysis remain unconfirmed by observed data, underscoring psychological and socioeconomic stressors as dominant post-accident health burdens.[28] [85]Debunking Exaggerated Risks

Exaggerated claims of Chernobyl's radiation causing millions of deaths or rendering the Pripyat area perpetually uninhabitable contradict epidemiological data from international assessments. The acute death toll from the accident stands at 31, comprising two immediate fatalities from the explosion and 29 from acute radiation syndrome among plant workers and firefighters exposed to doses exceeding 6 Gy.[2] Long-term projections by the World Health Organization, based on linear no-threshold models, estimated up to 4,000 excess cancer deaths among approximately 600,000 liquidators, evacuees, and residents over their lifetimes, yet subsequent UNSCEAR analyses through 2011 found no statistically significant increase in overall cancer incidence, mortality, or non-malignant disorders attributable to radiation beyond elevated thyroid cancers.[28][21] These thyroid cases, numbering around 6,000 primarily among children exposed to iodine-131 fallout, exhibit high cure rates exceeding 95% with early detection and treatment, underscoring that even this effect was localized and mitigable.[86] Media portrayals, such as those amplifying fears of widespread genetic mutations or "nuclear winter" scenarios, lack empirical support; genomic studies of children born to exposed parents detected no heritable radiation-induced mutations.[87] UNSCEAR reports emphasize that psychological distress from radiophobia—fueled by misinformation—has led to higher rates of stress-related illnesses, suicides, and unnecessary medical interventions than radiation itself in affected populations.[21] In Pripyat, current ambient gamma dose rates average 0.1–0.6 μSv/h in most areas, comparable to Ukraine's natural background of 0.08–0.3 μSv/h and far below levels posing acute risks, with hotspots confined to specific debris sites that decay over time via radioactive half-lives.[88][89] Visitors to the exclusion zone, including tourists, incur effective doses of 1–20 μSv per short tour—equivalent to 1–10 days of global average background exposure—without exceeding safety thresholds set by the International Commission on Radiological Protection.[2] Critiques of inflated estimates note incentives in post-Soviet states to attribute unrelated health declines to Chernobyl for international aid, as evidenced by discrepancies between national registries and independent verifications showing overreporting of non-radiation-linked conditions.[90] First-principles analysis of dose-response reveals that low-level chronic exposures in the zone, below 100 mSv lifetime cumulative, align with observations of negligible excess risk in analogous cohorts like Japanese atomic bomb survivors or medical radiology patients, challenging alarmist narratives that ignore dose rate and biological repair mechanisms.[85] Self-settlers numbering in the hundreds who returned to zone villages post-evacuation exhibit life expectancies and morbidity patterns indistinguishable from regional norms, further indicating that relocation-induced disruptions posed greater immediate harms than residual radiation.[2] These realities underscore how fear-driven policies have amplified perceived dangers beyond verifiable causal links.Wildlife and Biodiversity

Resurgence of Fauna and Flora

Following the 1986 Chernobyl disaster and subsequent evacuation of Pripyat, the absence of human activity in the surrounding exclusion zone facilitated a marked resurgence in both fauna and flora populations, outpacing expectations given persistent radiation levels. Empirical surveys indicate that the removal of hunting, agriculture, and urban development pressures enabled rapid ecological recovery, with biodiversity metrics comparable to or exceeding those in nearby protected areas unaffected by the accident. This rebound underscores the dominant role of anthropogenic disturbance over chronic low-level radiation in suppressing wildlife abundance.[91][92] Mammalian populations, in particular, demonstrated substantial growth. Camera trap and track surveys from 1997 to 2014 recorded abundances of elk (Alces alces), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), red deer (Cervus elaphus), and wild boar (Sus scrofa) in the exclusion zone at levels similar to four uncontaminated regional reserves, while gray wolf (Canis lupus) densities were over seven times higher. Helicopter censuses further documented increasing trends in elk, roe deer, and wild boar numbers within the first decade post-accident, with explosive growth in boar, elk, and roe deer populations observed between 1987 and 1996 in the Belarusian sector. Additional species, including Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), brown bears (Ursus arctos), European bison (Bison bonasus), and black storks (Ciconia nigra), have been confirmed via camera traps, contributing to over 60 rare species documented alongside hundreds of others. These data reveal no discernible negative correlation between radiation dose rates and overall mammal abundance after nearly three decades of exposure.[92][67][91] Flora has similarly reclaimed abandoned landscapes, with forest cover in the 2,800 km² exclusion zone expanding from 41% in 1986 to 59% by 2020, driven by natural afforestation and succession on former agricultural and urban lands. In Pripyat itself, urban trees—largely unimpacted by radiation—have persisted without maintenance since 1986, supporting regeneration patterns that favor mixed oak (Quercus robur) and linden (Tilia cordata) stands amid a mosaic of early-successional vegetation. Initial pine plantations have evolved into more diverse primary forests, enhancing habitat complexity and carbon storage. Remote sensing confirms elevated normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) values in urban zones, reflecting vigorous regrowth of grasses, shrubs, and trees encroaching on streets and buildings.[93][94][67] While sublethal radiation effects, such as reduced reproductive success in certain birds or genetic anomalies in rodents, have been noted in targeted studies, population-level data indicate these do not impede the broader resurgence, which aligns with patterns observed in other human-vacated areas. The exclusion zone's de facto status as a sanctuary—now the third-largest nature reserve in Ukraine—demonstrates that human exclusion can override radiation's ecological constraints for many taxa.[69][92]Implications for Nuclear Fear Narratives

The resurgence of wildlife populations in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ), encompassing Pripyat, has provided empirical evidence challenging apocalyptic narratives surrounding nuclear accidents, which often depict irradiated areas as perpetually sterile wastelands incapable of supporting life.[92] Long-term surveys, including aerial counts and camera traps, document elevated densities of large mammals—such as gray wolves, European bison, and wild boar—relative to non-irradiated reference sites in Ukraine and Belarus, with wolf populations estimated at 100-200 individuals by the early 2010s.[91] This boom, observed consistently since the 1990s, correlates primarily with the removal of human activity, including hunting, agriculture, and infrastructure, rather than radiation mitigation, as similar recovery patterns occur across varying contamination levels within the zone.[95] While chronic low-dose radiation imposes sublethal effects on individuals—evidenced by higher rates of cataracts, genetic mutations, and reduced reproductive success in species like birds and voles in high-radionuclide hotspots—these do not translate to population declines, as compensatory factors like reduced predation and abundant forage sustain overall abundance.[92] Peer-reviewed analyses from 2015, aggregating data from multiple methodologies, found no detectable negative correlation between radionuclide exposure and mammal biomass or diversity, contrasting with pre-accident human-dominated landscapes where biodiversity was suppressed.[96] Such findings refute claims in popular media and advocacy reports of ecosystem collapse, which amplify acute post-1986 die-offs (e.g., pine forest necrosis) into enduring desolation, often without accounting for ecological succession or comparative data from non-nuclear disturbed areas.[69] These observations carry broader implications for nuclear fear narratives, which frequently equate reactor accidents with irreversible environmental Armageddon akin to nuclear warfare, thereby fueling opposition to nuclear energy despite its low carbon footprint and safety record relative to fossil fuels.[96] The CEZ's transformation into a de facto wildlife refuge—hosting over 200 bird species and recolonized forests—demonstrates that moderate radiation fields, decaying over time (e.g., cesium-137 half-life of 30 years), permit rapid biotic recovery when anthropogenic pressures are absent, a dynamic overlooked in sensationalized accounts that prioritize human-centric risk models over ecosystem-level resilience.[91] This evidence supports a more nuanced view: nuclear incidents pose localized, manageable hazards rather than total biotic extinction events, potentially tempering exaggerated projections in policy debates where institutional biases, such as those in environmental NGOs, emphasize worst-case scenarios to advance non-nuclear agendas.[69]Access, Tourism, and Management

Regulatory Framework

The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (ChEZ), which includes the abandoned city of Pripyat, is administered by the State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management (DAZV), tasked with mitigating the 1986 disaster's consequences, ensuring radiation safety, conducting scientific monitoring, and regulating human activities within the 2,600 square kilometer area.[97] [98] The agency's mandate emphasizes preventing unauthorized exposure, containing radiological contamination, and facilitating controlled access for workers, researchers, and limited tourism, while prioritizing empirical radiation measurements over precautionary overrestrictions.[99] The primary legal foundation is Ukraine's 1991 Law "On the Legal Regime of the Exclusion Zone and the Zone of Unconditional (Obligatory) Resettlement," which delineates the ChEZ as a restricted territory subject to special administrative controls, including prohibitions on permanent residency, agriculture, and forestry without approval, to minimize health risks from residual radionuclides like cesium-137 and strontium-90.[100] Complementary oversight comes from the State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine (SNRIU), which enforces nuclear safety standards for facilities such as the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant decommissioning site, including licensing for waste management and sarcophagus maintenance.[101] DAZV has proposed zoning the ChEZ into categories aligned with International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) guidelines—distinguishing high-contamination inner areas from lower-risk outer zones—to enable evidence-based land use decisions, such as potential agricultural repurposing where dose rates permit.[99][102] Entry to Pripyat and the broader ChEZ requires a permit from DAZV under Regulation No. 1157, obtainable only by individuals aged 18 or older without medical contraindications to low-level ionizing radiation exposure, with applications submitted at least 10 working days in advance via licensed operators or official channels.[103] Permits stipulate guided tours along predefined routes, mandatory dosimetry checks at entry and exit points (e.g., Dytiatky checkpoint) to ensure cumulative doses remain below 1 millisievert per visit, and prohibitions on deviating from paths, entering structurally compromised buildings, or removing artifacts to avoid dust inhalation or contamination transfer.[104][105] Violations, including illegal entry, incur fines up to 170 non-taxable minimum incomes or administrative detention, enforced through patrols and monitoring systems. Since Russia's 2022 invasion, martial law has periodically suspended tourist permits, with DAZV reinstating controls post-deoccupation to restore radiation monitoring infrastructure damaged during occupation.[106][107] Radiation safety protocols mandate real-time monitoring with portable dosimeters, adherence to IAEA-derived limits (e.g., annual public exposure under 1 millisievert beyond natural background), and decontamination procedures for vehicles and personnel exiting the zone.[108] These measures reflect causal assessments of actual exposure pathways—primarily external gamma radiation and groundshine in Pripyat's urban decay—rather than undifferentiated fear of "nuclear wasteland," as empirical data indicate average visitor doses comparable to a transatlantic flight. International cooperation, including IAEA technical assistance and European Bank for Reconstruction and Development funding ratified in 2024, supports framework enhancements like updated decommissioning licenses and waste repositories.[109][110]Tourism Development and Visitor Safety

Tourism to Pripyat within the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone began as informal visits by looters in the 1990s but evolved into organized, regulated excursions after the Ukrainian government officially permitted access for tourists over age 18 in 2011.[111][112] These day trips, typically originating from Kyiv, focus on Pripyat's abandoned Soviet-era structures, including the unfinished amusement park, Polissya Hotel, and Palace of Culture, drawing "dark tourism" enthusiasts interested in the site's historical and atmospheric remnants of the 1986 disaster.[112] Visitor numbers surged pre-2022, with annual figures reaching record highs and growing approximately 35% year-over-year by 2021 due to enhanced safety protocols and global media attention from the HBO miniseries Chernobyl.[113] Access halted following Russia's February 2022 invasion, which temporarily placed the zone under occupation, though Ukrainian authorities announced plans in June 2025 to revive tourism with new visitor centers, improved infrastructure, and expanded educational exhibits to promote the site as a hub for nuclear history rather than mere ruins.[40][114] Visitor safety is enforced through mandatory licensed guides, advance permits from the State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management, and multiple checkpoints where passports and vehicles are inspected.[104] Participants must adhere to strict guidelines: wearing closed-toe shoes and long-sleeved clothing to minimize skin exposure, prohibiting touch of vegetation or structures to avoid dust inhalation, and restricting eating, smoking, or drinking outdoors; dosimeters are issued to monitor personal exposure, with tours avoiding known hotspots like the reactor shelter.[104][115] Radiation levels in Pripyat's accessible areas average 0.5–2 microsieverts per hour—comparable to background radiation in parts of the world like Ramsar, Iran—and a standard one-day tour delivers a total dose of under 0.1 millisieverts, equivalent to 3–5 hours of air travel or a few days of natural exposure in Kyiv.[116][117] No adverse health effects have been documented among the hundreds of thousands of tourists since 2011, underscoring that risks are negligible when protocols are followed, contrary to sensationalized narratives exaggerating the zone's dangers for short visits.[118] As of October 2025, the zone remains closed to civilians amid ongoing conflict, with access limited to official delegations, though operators emphasize that pre-war measures ensured safety comparable to other regulated heritage sites.[119][118]Impacts of Geopolitical Conflicts