Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Lacrimal punctum.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lacrimal punctum

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| Lacrimal punctum | |

|---|---|

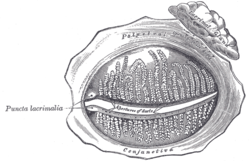

The tarsal glands, etc., seen from the inner surface of the eyelids. (Puncta lacrimalia visible at center left.) | |

The lacrimal apparatus. Right side. Note outdated terminology: The "Lacrimal ducts" in Gray's are now called "Lacrimal canals". | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | puncta lacrimalia |

| TA98 | A15.2.07.065 |

| TA2 | 6854 |

| FMA | 59365 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The lacrimal punctum (pl.: puncta) or lacrimal point is a minute opening on the summits of the lacrimal papillae, seen on the margins of the eyelids at the lateral extremity of the lacrimal lake. There are two lacrimal puncta in the medial (inside) portion of each eyelid. Normally, the puncta dip into the lacrimal lake.

Together, they function to collect tears produced by the lacrimal glands. The fluid is conveyed through the lacrimal canaliculi to the lacrimal sac, and thence via the nasolacrimal duct to the inferior nasal meatus of the nasal passage.

Additional images

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1028 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1028 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

External links

[edit]- Diagram and discussion at aafp.org Archived 2011-10-20 at the Wayback Machine

Lacrimal punctum

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

The lacrimal punctum (plural: lacrimal puncta) is a small opening located at the medial margin of each upper and lower eyelid, approximately 6 mm from the medial canthus, serving as the initial entry point for tears into the lacrimal drainage system.[1][2] Each punctum measures about 0.2 to 0.3 mm in diameter and is positioned to collect tears from the ocular surface during blinking, which activates the surrounding orbicularis oculi muscle to facilitate drainage.[1][3] There are four puncta in total—two per eye (one superior and one inferior)—and they connect directly to short vertical canaliculi that transition into horizontal canaliculi, ultimately merging into the lacrimal sac before tears flow through the nasolacrimal duct into the nasal cavity.[2][3]