Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Maxilla

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

| Maxilla | |

|---|---|

Position of the maxilla | |

Animation of the maxilla | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | First branchial arch[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | maxilla |

| MeSH | D008437 |

| TA98 | A02.1.12.001 |

| TA2 | 756 |

| FMA | 9711 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

In vertebrates, the maxilla (pl.: maxillae /mækˈsɪliː/)[2] is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth.[3][4] The two maxillary bones are fused at the intermaxillary suture, forming the anterior nasal spine. This is similar to the mandible (lower jaw), which is also a fusion of two mandibular bones at the mandibular symphysis. The mandible is the movable part of the jaw.

Anatomy

[edit]Structure

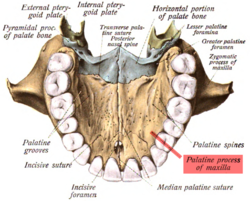

[edit]The maxilla is a paired bone - the two maxillae unite with each other at the intermaxillary suture. The maxilla consists of:[5]

- The body of the maxilla: pyramid-shaped; has an orbital, a nasal, an infratemporal, and a facial surface; contains the maxillary sinus.

- Four processes:

- the zygomatic process

- the frontal process

- the alveolar process

- the palatine process

It has three surfaces:[5]

- the anterior, posterior, medial

Features of the maxilla include:[5]

- the infraorbital sulcus, canal, and foramen

- the maxillary sinus

- the incisive foramen

Articulations

[edit]Each maxilla articulates with nine bones: frontal, ethmoid, nasal, zygomatic, lacrimal, and palatine bones, the vomer, the inferior nasal concha, as well as the maxilla of the other side.[5]

Sometimes it articulates with the orbital surface, and sometimes with the lateral pterygoid plate of the sphenoid.

Development

[edit]

The maxilla is ossified in membrane. Mall and Fawcett maintain that it is ossified from two centers only, one for the maxilla proper and one for the premaxilla.[6][7]

These centers appear during the sixth week of prenatal development and unite in the beginning of the third month, but the suture between the two portions persists on the palate until nearly middle life. Mall states that the frontal process is developed from both centers.

The maxillary sinus appears as a shallow groove on the nasal surface of the bone about the fourth month of development, but does not reach its full size until after the second dentition.

The maxilla was formerly described as ossifying from six centers, viz.:

- One, the orbitonasal, forms that portion of the body of the bone which lies medial to the infraorbital canal, including the medial part of the floor of the orbit and the lateral wall of the nasal cavity.

- A second, the zygomatic, gives origin to the portion which lies lateral to the infraorbital canal, including the zygomatic process.

- From a third, the palatine, is developed the palatine process posterior to the incisive canal together with the adjoining part of the nasal wall.

- A fourth, the premaxillary, forms the incisive bone which carries the incisor teeth and corresponds to the premaxilla of the lower vertebrates.

- A fifth, the nasal, gives rise to the frontal process and the portion above the canine tooth.

- And a sixth, the infravomerine, lies between the palatine and premaxillary centers and beneath the vomer; this center, together with the corresponding center of the opposite bone, separates the incisive canals from each other.

Changes by age

[edit]At birth the transverse and antero-posterior diameters of the bone are each greater than the vertical.

The frontal process is well-marked and the body of the bone consists of little more than the alveolar process, the teeth sockets reaching almost to the floor of the orbit.

The maxillary sinus presents the appearance of a furrow on the lateral wall of the nose. In the adult the vertical diameter is the greatest, owing to the development of the alveolar process and the increase in size of the sinus.

Function

[edit]

The alveolar process of the maxillae holds the upper teeth, and is referred to as the maxillary arch. Each maxilla attaches laterally to the zygomatic bones (cheek bones).

Each maxilla assists in forming the boundaries of three cavities:

- the roof of the mouth

- the floor and lateral wall of the nasal cavity

- the wall of the orbit

Each maxilla also enters into the formation of two fossae: the infratemporal and pterygopalatine, and two fissures, the inferior orbital and pterygomaxillary. -When the tender bones of the upper jaw and lower nostril are severely or repetitively damaged, at any age the surrounding cartilage can begin to deteriorate just as it does after death.[citation needed]

Clinical significance

[edit]A maxilla fracture is a form of facial fracture. A maxilla fracture is often the result of facial trauma such as violence, falls or automobile accidents. Maxilla fractures are classified according to the Le Fort classification.

In other animals

[edit]Sometimes (e.g. in bony fish), the maxilla is called "upper maxilla", with the mandible being the "lower maxilla". Conversely, in birds the upper jaw is often called "upper mandible".

In most vertebrates, the foremost part of the upper jaw, to which the incisors are attached in mammals consists of a separate pair of bones, the premaxillae. These fuse with the maxilla proper to form the bone found in humans, and some other mammals. In bony fish, amphibians, and reptiles, both maxilla and premaxilla are relatively plate-like bones, forming only the sides of the upper jaw, and part of the face, with the premaxilla also forming the lower boundary of the nostrils. However, in mammals, the bones have curved inward, creating the palatine process and thereby also forming part of the roof of the mouth.[8]

Birds do not have a maxilla in the strict sense; the corresponding part of their beaks (mainly consisting of the premaxilla) is called "upper mandible".

Cartilaginous fish, such as sharks, also lack a true maxilla. Their upper jaw is instead formed from a cartilaginous bar that is not homologous with the bone found in other vertebrates.[8]

Additional images

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 157 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 157 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ hednk-023—Embryo Images at University of North Carolina

- ^ OED 2nd edition, 1989.

- ^ Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary.

- ^ Fehrenbach; Herring (2012). Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck. Elsevier. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4377-2419-6.

- ^ a b c d Fehrenbach, Margaret J.; Herring, Susan W. (2017). Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck (5th ed.). St. Louis: Elsevier. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-323-39634-9.

- ^ Mall, Franklin P. (1906). "On ossification centers in human embryos less than one hundred days old". American Journal of Anatomy. 5 (4): 433–458. doi:10.1002/aja.1000050403.

- ^ Fawcett, Edward (1911). "Some Notes on the Epiphyses of the Ribs". Journal of Anatomy and Physiology. 45 (Pt 2): 172–178. PMC 1288875. PMID 17232872.

- ^ a b Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 217–43. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

Further reading

[edit]- Sicher, Harry; Du Brul, E. Lloyd (1975). Oral Anatomy (6th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 0-8016-4604-9.

- Worthington, Philip; Evans, John R., eds. (1994). Controversies in Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-3099-5.

External links

[edit]- Anatomy photo:22:os-1901 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center