Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Eyelid

View on Wikipedia| Eyelid | |

|---|---|

| |

The same eye with its eyelid pulled open, displaying meibomian glands on the inside and a set of lashes growing in multiple layers | |

| Details | |

| System | Integumentary |

| Function | Covers and protects the eye by blinking or closing, keeping the cornea moist |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | palpebrae |

| MeSH | D005143 |

| TA98 | A15.2.07.024 |

| TA2 | 114, 115 |

| FMA | 54437 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

This article about biology may be excessively human-centric. (June 2019) |

An eyelid (/ˈaɪ.lɪd/ EYE-lid) is a thin fold of skin that covers and protects an eye. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle retracts the eyelid, exposing the cornea to the outside, giving vision. This can be either voluntarily or involuntarily. "Palpebral" (and "blepharal") means relating to the eyelids. Its key function is to regularly spread the tears and other secretions on the eye surface to keep it moist, since the cornea must be continuously moist. They keep the eyes from drying out when asleep. Moreover, the blink reflex protects the eye from foreign bodies. A set of specialized hairs known as lashes grow from the upper and lower eyelid margins to further protect the eye from dust and debris.

The appearance of the human upper eyelid often varies between different populations. The prevalence of an epicanthic fold covering the inner corner of the eye account for the majority of East Asian and Southeast Asian populations, and is also found in varying degrees among other populations. Separately, but also similarly varying between populations, the crease of the remainder of the eyelid may form either a "single eyelid", a "double eyelid", or an intermediate form.

Eyelids can be found in other animals, some of which may have a third eyelid, or nictitating membrane. A vestige of this in humans survives as the plica semilunaris.

Structure

[edit]Layers

[edit]The eyelid is made up of several layers; from superficial to deep, these are: skin, subcutaneous tissue, orbicularis oculi, orbital septum and tarsal plates, and palpebral conjunctiva. The meibomian glands lie within the eyelid and secrete the lipid part of the tear film.

Skin

[edit]The skin is similar to areas elsewhere, but is relatively thin[1] and has more pigment cells. In diseased persons, these may wander and cause a discoloration of the lids. It contains sweat glands and hairs, the latter becoming eyelashes as the border of the eyelid is met.[2] The skin of the eyelid contains the greatest concentration of sebaceous glands found anywhere in the body.[1]

Nerve supply

[edit]In humans, the sensory nerve supply to the upper eyelids is from the infratrochlear, supratrochlear, supraorbital and the lacrimal nerves from the ophthalmic branch (V1) of the trigeminal nerve (CN V). The skin of the lower eyelid is supplied by branches of the infratrochlear at the medial angle. The rest is supplied by branches of the infraorbital nerve of the maxillary branch (V2) of the trigeminal nerve.

Blood supply

[edit]In humans, the eyelids are supplied with blood by two arches on each upper and lower lid. The arches are formed by anastomoses of the lateral palpebral arteries and medial palpebral arteries, branching off from the lacrimal artery and ophthalmic artery, respectively.

Eyelashes

[edit]

The eyelashes (or simply lashes) are hairs that grow on the edges of the upper and lower eyelids. The lashes are short (upper lashes are typically just 7 to 8 mm in length) hairs, though can be exceptionally long (occasionally up to 15 mm in length) and prominent in some individuals with trichomegaly. The lashes protect the eye from dust and debris by catching them via rapid blinking when the blink reflex is triggered by the debris touching the lashes. Long lashes also play a significant part in facial attractiveness.

Function

[edit]The eyelids close or blink voluntarily and involuntarily to protect the eye from foreign bodies, and keep the surface of the cornea moist. The upper and lower human eyelids feature a set of eyelashes which grow in up to 6 rows along each eyelid margin, and serve to heighten the protection of the eye from dust and foreign debris, as well as from perspiration.

Clinical significance

[edit]Any condition that affects the eyelid is called eyelid disorder. The most common eyelid disorders, their causes, symptoms and treatments are the following:

- Hordeolum (stye) is an infection of the sebaceous glands of Zeis usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, similar to the more common condition Acne vulgaris. It is characterized by an acute onset of symptoms and it appears similar to a red bump placed underneath the eyelid. The main symptoms of styes include pain, redness of the eyelid and sometimes swollen eyelids. Styes usually disappear within a week without treatment. Otherwise, antibiotics may be prescribed and home remedies such as warm water compresses may be used to promote faster healing. Styes are normally harmless and do not cause long lasting damage.

- Chalazion (plural: chalazia) is caused by the obstruction of the oil glands and can occur in both upper and lower eyelids. Chalazia may be mistaken for styes due to the similar symptoms. This condition is however less painful and it tends to be chronic. Chalazia heal within a few months if treatment is administered and otherwise they can resorb within two years. Chalazia that do not respond to topical medication are usually treated with surgery as a last resort.

- Blepharitis is the irritation of the lid margin, where eyelashes join the eyelid. This is a common condition that causes inflammation of the eyelids and which is quite difficult to manage because it tends to recur.[3] This condition is mainly caused by staphylococcus infection and scalp dandruff. Blepharitis symptoms include burning sensation, the feeling that there is something in the eye, excessive tearing, blurred vision, redness of the eye, light sensitivity, red and swollen eyelids, dry eye and sometimes crusting of the eyelashes on awakening. Treatment normally consists in maintaining a good hygiene of the eye and holding warm compresses on the affected eyelid to remove the crusts. Gently scrubbing the eyelid with the warm compress is recommended as it eases the healing process. In more serious cases, antibiotics may be prescribed.

- Demodex mites are a genus of tiny mites that live as commensals in and around the hair follicles of numerous mammals including humans, cats and dogs. Human demodex mites typically live in the follicles of the eyebrows and eyelashes. While normally harmless, human demodex mites can sometimes cause irritation of the skin (demodicosis) in persons with weakened immune systems.

- Entropion usually results from aging, but sometimes can be due to a congenital defect, a spastic eyelid muscle, or a scar on the inside of the lid that could be from surgery, injury, or disease.[medical citation needed] It is an asymptomatic condition that can, rarely, lead to trichiasis, which requires surgery. It mostly affects the lower lid, and is characterized by the turning inward of the lid, toward the globe.

- Ectropion is another aging-related eyelid condition that may lead to chronic eye irritation and scarring. It may also be the result of allergies and its main symptoms are pain, excessive tearing and hardening of the eyelid conjunctiva.

- Laxity is also another aging-related eyelid condition that can lead to dryness and irritation. Surgery may be necessary to repair the eyelid to its natural position. In certain instances, excessive lower lid laxity creates the Fornix of Reiss – a pocket between the lower eyelid and globe – which is the ideal location to administer topical ophthalmic medications.

- Eyelid edema is a condition in which the eyelids are swollen and tissues contain excess fluid. It may affect eye function when it increases the intraocular pressure. Eyelid edema is caused by allergy, trichiasis or infections.[4] The main symptoms are swollen red eyelids, pain, and itching. Chronic eyelid edema can lead to blepharochalasis.

- Eyelid tumors may also occur. Basal cell carcinomas are the most frequently encountered kind of cancer affecting the eyelid, making up 85–95% of all malignant eyelid tumors.[5] The tumors may be benign or malignant. Usually benign tumors are localized and removed before becoming a cancerous threat and before they become large enough to impair vision. Malignant tumors on the other hand tend to spread to surrounding areas and tissues.

- Blepharospasm (eyelid twitching) is an involuntary spasm of the eyelid muscle. The most common factors that make the muscle in the eyelid twitch are fatigue, stress, and caffeine.[6] Eyelid twitching is not considered a harmful condition and therefore there is no treatment available. Patients are however advised to get more sleep and drink less caffeine.

- Eyelid dermatitis is the inflammation of the eyelid skin. It is mostly a result of allergies or contact dermatitis of the eyelid. Symptoms include dry and flaky skin on the eyelids and swollen eyelids. The affected eyelid may itch. Treatment consists in proper eye hygiene and avoiding the allergens that trigger the condition. In rare cases, topical creams may be used but only under a doctor's supervision.

- Ptosis (drooping eyelid) is when the upper eyelid droops or sags due to weakness or paralysis of the levator muscle (responsible for raising the eyelid), or due to damage to nerves controlling the muscle. It can be a manifestation of the normal aging process, a congenital condition, or due to an injury or disease. Risk factors related to ptosis include diabetes, stroke, Horner syndrome, Bell's Palsy (compression/damage to Facial nerve), myasthenia gravis, brain tumor or other cancers that can affect nerve or muscle function.

- Ablepharia (ablepharon) is the congenital absence of or reduction in the size of the eyelids.[7]

Surgery

[edit]The eyelid surgeries are called blepharoplasties and are performed either for medical reasons or to alter one's facial appearance.

Most of the cosmetic eyelid surgeries are aimed to enhance the look of the face and to boost self-confidence by restoring a youthful eyelid appearance. They are intended to remove fat and excess skin that may be found on the eyelids after a certain age.

Eyelid surgeries are also performed to improve peripheral vision or to treat chalazion, eyelid tumors, ptosis, ectropion, trichiasis, and other eyelid-related conditions.

Eyelid surgeries are overall safe procedures but they carry certain risks since the area on which the operation is performed is so close to the eye.

Anatomical variation

[edit]

An anatomical variation in humans occurs in the creases and folds of the upper eyelid.

An epicanthic fold, the skin fold of the upper eyelid covering the inner corner (medial canthus) of the eye, may be present based on various factors, including ancestry, age, and certain medical conditions. In some populations the trait is almost universal, specifically in East Asians and Southeast Asians, where a majority, up to 90% in some estimations, of adults have this feature.[8]

The upper eyelid crease is a common variation between people of White and East Asian ethnicities.[9] Westerners commonly perceive the East Asian upper eyelid as a "single eyelid".[9] However, East Asian eyelids are divided into three types – single, low, and double – based on the presence or position of the lid crease.[10] Jeong Sang-ki et al. of Chonnam University, Kwangju, Korea, in a study using both Asian and White cadavers as well as four healthy young Korean men, said that "Asian eyelids" have more fat in them than those of White people.[9] Single/double eyelids are polygenic traits.[11] A 2011 study also states that Saudis of "pure Arab" descent generally have higher upper lid crease and upper lid skin fold heights, compared to other ethnic groups.[12]

In some individuals, an eyelid with excessive skin may push the eyelashes downwards and into the eye, obstructing vision in the case of long and thick lashes, and potentially causing corneal abrasion.[13]

Prevalence

[edit]| Year | Ethnic group | Gender | Prevalence of double eyelid |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1896 | Japanese | Female | 82–83% |

| 2000 | Chinese Singaporean | Female | 66.7% |

| 2007 | Korean | Male | 24.1% |

| Female | 45.5% | ||

| 2008 | Asian | Male | 30.3% |

| Female | 41.3% | ||

| 2009 | Asian | N/A | 50.0% |

| 2013 | Taiwanese | Female | 83.1% |

Society and culture

[edit]Cosmetic surgery

[edit]Blepharoplasty is a cosmetic surgical procedure performed to correct deformities and improve or modify the appearance of the eyelids.[15] With 1.43 million people undergoing the procedure in 2014,[16] blepharoplasty is the second most popular cosmetic procedure in the world (Botulinum toxin injection is first), and the most frequently performed cosmetic surgical procedure in the world.[17]

East Asian blepharoplasty, or "double eyelid surgery", has been reported to be the most common aesthetic procedure in Taiwan and South Korea.[18] Though the procedure is also used to reinforce muscle and tendon tissues surrounding the eye, the operative goal of East Asian blepharoplasty is to remove the adipose and linear tissues underneath and surrounding the eyelids in order to crease the upper eyelid.[19] A procedure to remove the epicanthal fold (i.e. an epicanthoplasty) is often performed in conjunction with an East Asian blepharoplasty.[20]

The use of double sided tape or eyelid glue to create the illusion of creased, or "double" eyelids has become a prominent practice in China and other Asian countries. There is a social pressure for women to have this surgery, and also to use the alternative (taping) practices.[21] Blepharoplasty has become a common surgical operation that is actively encouraged, whilst other kinds of plastic surgery are actively discouraged in Chinese culture.[22]

Death

[edit]After death, it is common in many cultures to pull the eyelids of the deceased down to close the eyes. This is a typical part of the last offices.

Additional images

[edit]-

Horizontal section through the eye of an eighteen days' embryo rabbit. X 30

-

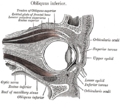

Sagittal section of right orbital cavity

-

Sagittal section through the upper eyelid

-

The tarsi and their ligaments. Right eye; front view

-

The lacrimal apparatus. Right side

-

Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection

See also

[edit]- Cellulitis – a bacterial infection involving the inner layers of the skin

- Dermatochalasis – an excess of eyelid skin that may obstruct vision

- Gland of Moll – a modified sweat gland at the base of the eyelashes

- Hay-Wells syndrome – a disorder often causing fusion of the eyelids

- Nictitating membrane – a third eyelid present in some animals

References

[edit]- ^ a b Goldman, Lee (25 July 2011). Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. p. 2426. ISBN 978-1437727883.

- ^ "eye, human." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2010.

- ^ "Facts About Blepharitis". Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ "Upper Eyelid Edema Treatment and Symptoms". Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ "Eyelid and Orbital Tumors". Retrieved 30 March 2010. "Eyelid and Orbital Tumours". Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ "Eyelid twitch". Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary, Edition 21, Page-6.

- ^ Lee, Y., Lee, E. and, Park, W.J. (2000) Anchor epicanthoplasty combined with outfold type double eyelidplasty for Asians: do we have to make an additional scar to correct the Asian epicanthal fold? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 105:1872–1880

- ^ a b c Jeong S, Lemke BN, Dortzbach RK, Park YG, Kang HK (July 1999). "The Asian upper eyelid: an anatomical study with comparison to the White eyelid". Archives of Ophthalmology. 117 (7): 907–12. doi:10.1001/archopht.117.7.907. PMID 10408455.

- ^ Han, M. H., & Kwon, S. T. (1992). A statistical study of upper eyelids of Korean young women. Journal of the Korean Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons, 19(6), 930-935.

- ^ Wang, Peiqi; et al. (2022). "Novel genetic associations with five aesthetic facial traits: A genome-wide association study in the Chinese population". Frontiers in Genetics. 13. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.967684. PMC 9411802. PMID 36035146.

- ^ Bukhari, Amal A. (2011). "The distinguishing anthropometric features of the Saudi Arabian eyes". Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology. 25 (4): 417–420. doi:10.1016/j.sjopt.2011.05.004. PMC 3729392. PMID 23960957.

- ^ Paik, Ji Sun; Lee, Ji Hyeong; Uppal, Sandeep; Choi, Woong Chul (October 2020). "Intricacies of Upper Blepharoplasty in Asian Burden Lids". Facial Plastic Surgery. 36 (5): 563–574. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1718391. ISSN 0736-6825. PMID 33368080.

- ^ Lu, Ting Yin; Kadir, Kathreena; Ngeow, Wei Cheong; Othman, Siti Adibah (1 November 2017). "The Prevalence of Double Eyelid and the 3D Measurement of Orbital Soft Tissue in Malays and Chinese". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 14819. Bibcode:2017NatSR...714819L. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-14829-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5665901. PMID 29093554.

- ^ "Eyelid Surgery". American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Rosie. "July 2015 ISAPS Global Statistics Release." International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2015): n. pag. Web. 8 Jul 2015. http://www.isaps.org/Media/Default/global-statistics/July%202015%20ISAPS%20Global%20Statistics%20Release%20-%20Final.pdf Archived 24 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Quick Facts: Highlights of the ISAPS 2014 Statistics on Cosmetic Surgery." International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2015). Web. http://www.isaps.org/Media/Default/global-statistics/Quick%20Facts%202015v2.pdf Archived 22 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Liao WC, Tung TC, Tsai TR, Wang CY, Lin CH (2005). "Celebrity arcade suture blepharoplasty for double eyelid". Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 29 (6): 540–5. doi:10.1007/s00266-005-0012-5. PMID 16237581. S2CID 11063260.

- ^ "Blepharoplasty". www.mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic. 27 April 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ Yen MT, Jordan DR, Anderson RL (January 2002). "No-scar Asian epicanthoplasty: a subcutaneous approach". Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 18 (1): 40–4. doi:10.1097/00002341-200201000-00006. PMID 11910323. S2CID 42228889.

- ^ Levinovitz, Alan (22 October 2013). "Chairman Mao Invented Traditional Chinese Medicine". Slate (magazine). Retrieved 2 July 2016

- ^ Cornell, Joanna. "In the Eyelids of the Beholder." Yale Globalist (2010): n. pag. Web. 2 Mar 2011. http://tyglobalist.org/perspectives/in-the-eyelids-of-the-beholder/ Archived 3 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

[edit]- "eye, human."Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD 2009.