Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pygostyle

View on Wikipedia

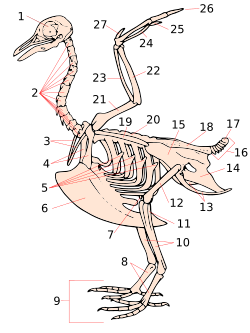

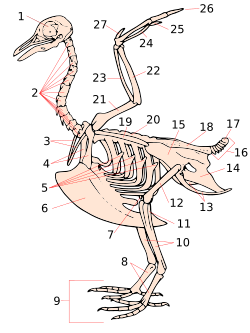

Pygostyle (/ˈpaɪɡəˌstaɪl/; from Ancient Greek πυγή [pugḗ] 'tail, rump' and στῦλος [stûlos] 'pillar, column') is a skeletal condition in which the final few caudal vertebrae are fused into a single ossification, supporting the tail feathers and musculature. In modern birds, the rectrices attach to these. The pygostyle is the main component of the uropygium, a structure colloquially known as the bishop's nose, parson's nose, pope's nose, or sultan's nose. This is the fleshy protuberance visible at the posterior end of a bird (most commonly a chicken or turkey) that has been dressed for cooking. It has a swollen appearance because it also contains the uropygial gland that produces preen oil.

Evolution

[edit]Pygostyles probably began to evolve very early in the Cretaceous period, perhaps 140 – 130 million years ago. The earliest known species to have evolved a pygostyle were members of the Confuciusornithidae.[citation needed] The structure provided an evolutionary advantage, as a completely mobile tail as found in species such as Archaeopteryx is detrimental to its use for flight control. Modern birds still develop longer caudal vertebrae in their embryonic state, which later fuse to form a pygostyle.

There are two main types of pygostyle:[citation needed] one, found in Confuciusornithidae, Enantiornithes, and some other Mesozoic birds, as well as in some oviraptorosaurs like Nomingia, is long and rod- or dagger blade-like. None of the known fossils with such pygostyles show traces of well-developed rectrices. The tail feathers in these animals consisted of downy fuzz and sometimes 2–4 central "streamers" such as those found in some specimens of Confuciusornis or in Paraprotopteryx.[1]

By contrast, the function of the pygostyle in the terrestrial Nomingia is not known. It is notable however that its older relative Caudipteryx had no pygostyle but a "fan" of symmetrical feathers which were probably used in social display. Perhaps such ornaments were widespread in Caenagnathoidea and their relatives, and ultimately the oviraptorosaurian pygostyle evolved to help support them. The related Similicaudipteryx, described in 2008, also had a rod-like pygostyle, associated with a fan of tail feathers.[2]

The other pygostyle type is plowshare-shaped. It is found in Ornithurae (living birds and their closest relatives), and in almost all flying species is associated with an array of well-developed rectrices used in maneuvering. The central pair of these attach directly to the pygostyle, just as in Confuciusornis. The other rectrices of Ornithurae are held in place and moved by structures called bulbi rectricium (rectricial bulbs), a complex feature of fat and muscles located on either side of the pygostyle. The oldest known species with such a pygostyle is Hongshanornis longicresta.[3]

As evidenced by the oviraptorosaurian cases, the pygostyle evolved at least twice, and rod-shaped pygostyles seem to have evolved several times, in association with shortening of the tail but not necessarily with a retractable fan of tail feathers. In other words, the pygostyles of oviraptorosaurs and Confuciusornis were likely weight-saving measures, and the specialized "true" pygostyles of ornithurans were adapted from these later to improve flight performance.[1]

The bird clade Pygostylia was named in 1996, by Luis Chiappe, for the presence of this feature and roughly corresponds to its appearance in the bird family tree, though the feature itself is not included in its definition.[4] In 2001, Jacques Gauthier and Kevin de Queiroz (2001) re-defined Pygostylia to refer specifically to the apomorphy of a short tail bearing an avian pygostyle.

Etymology

[edit]"Pygostyle" is formed from Ancient Greek words, literally meaning "rump pillar".

The insulting equation of the pygostyle with the noses of dignitaries dates back to 18th century Britain where pope's nose first appears (in 1786). The form parson's nose appears much later, dated to 1839. The usage is somewhat dependent on either a Catholic or Protestant viewpoint.[5]

The forms bishop's nose and sultan's nose are 20th century variants.

As food

[edit]Turkey tail or turkey butt has an international exportation market in places such as Micronesia, Samoa, and Ghana. The turkey tail is commonly exported from America because it is considered unhealthy and cut off the normal turkey.[6] After World War II, cheap imported turkey tails became popular in Samoa. Because the cut has a very high fat content, it was banned from 2007 to 2013 to combat obesity, only allowed back when Samoa joined the World Trade Organization. The meat is otherwise used in pet food.[7]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Clarke et al. (2006)

- ^ Xu, X.; Zheng, X.; You, H. (2010). "Exceptional dinosaur fossils show ontogenetic development of early feathers". Nature. 464 (7293): 1338–1341. Bibcode:2010Natur.464.1338X. doi:10.1038/nature08965. PMID 20428169. S2CID 205220207.

- ^ O'Connor, J.K.; Gao, K.-Q.; Chiappe, L.M. (2010). "A new ornithuromorph (Aves: Ornithothoraces) bird from the Jehol Group indicative of higher-level diversity" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (2): 311–321. Bibcode:2010JVPal..30..311O. doi:10.1080/02724631003617498. S2CID 53489175.

- ^ Chiappe, L. (1997). "The Chinese early bird Confuciusornis and the paraphyletic status of Sauriurae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (3): 37A. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10011028.

- ^ "Green's Dictionary of Slang". Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ Singer, Merrill (2014). "Following the turkey tails: neoliberal globalization and the political ecology of health" (PDF). Journal of Political Ecology. 21: 436–451. Bibcode:2014JPolE..2121145S. doi:10.2458/v21i1.21145.

- ^ Robert Siegel (2013-05-09). "Samoans Await The Return Of The Tasty Turkey Tail". NPR.

References

[edit]- Clarke, Julia A.; Zhou, Zhonghe; Zhang, Fucheng (2006). "Insight into the evolution of avian flight from a new clade of Early Cretaceous ornithurines from China and the morphology of Yixianornis grabaui". Journal of Anatomy. 208 (3): 287–308. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00534.x. PMC 2100246. PMID 16533313. Electronic Appendix

- He, T.; Wang, X.-L.; Zhou, Z.-H. (2008). "A new genus and species of caudipterid dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of western Liaoning, China". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 46 (3): 178–189.