Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

RAF Fauld explosion

View on Wikipedia

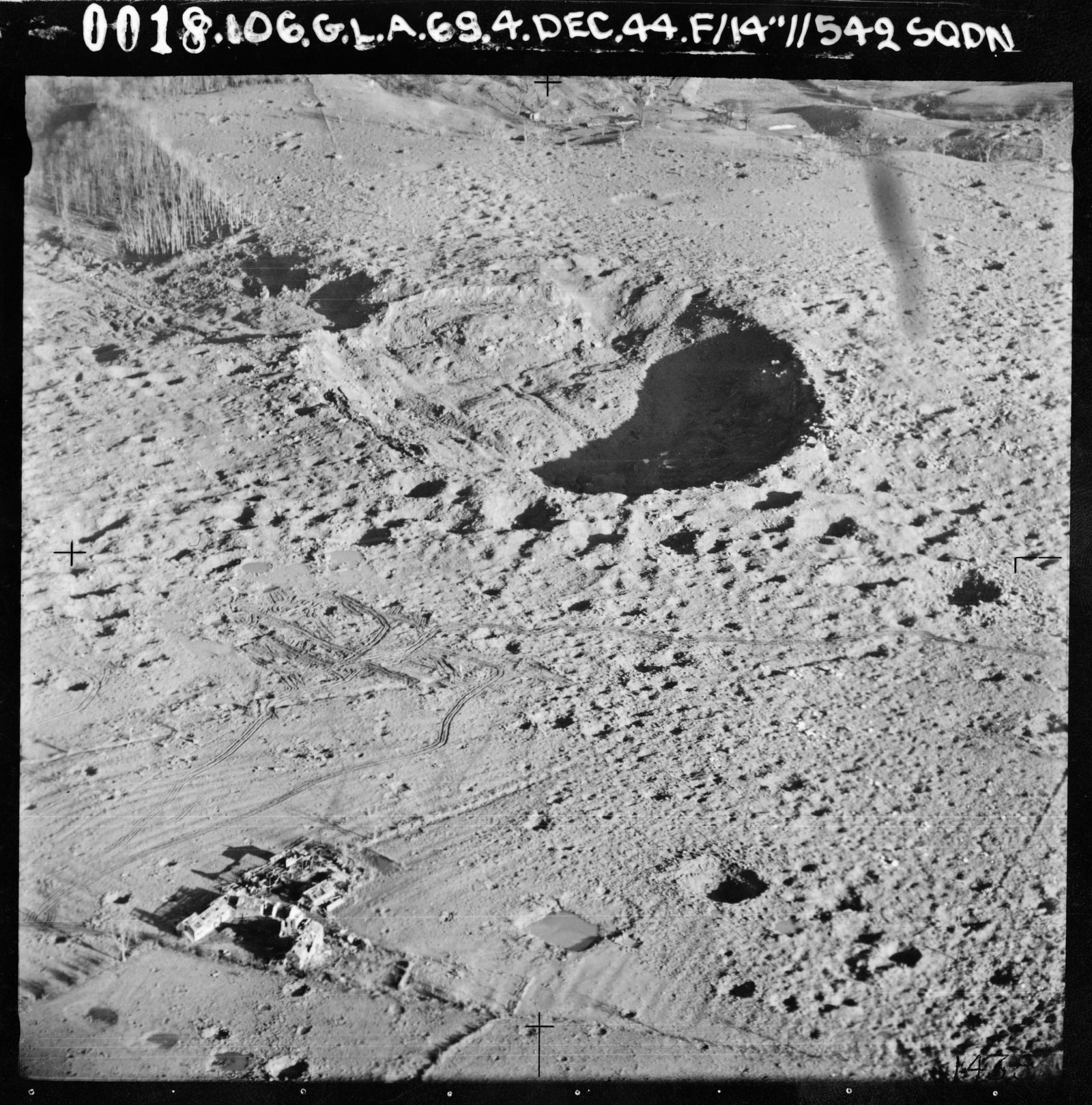

The RAF Fauld explosion occurred during the Second World War at the RAF Fauld underground munitions storage depot in Staffordshire, England at 11:11 am on Monday, 27 November 1944. The blast, which was one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history and the largest on UK soil detonated between 3,500 and 4,000 tonnes (3,900 and 4,400 tons) of high explosive military ordnance. It created an explosion crater with a depth of 100 feet (30 m) and a maximum width of 1,007 feet (307 m).[1]

Key Information

A reservoir containing 450,000 cubic metres (16,000,000 cu ft) of water was obliterated, along with nearby buildings and an entire farm. Flooding from the reservoir added to the destruction.[2]

A combination of the power of the explosion and wartime censorship in the UK means that the exact death toll is uncertain; it is believed that about 70 people died in the explosion and resulting flood.[3] The crater, which is now known as the Hanbury Crater, is still visible just south of Fauld, to the east of Hanbury, Staffordshire.[4][5][3]

Explosion

[edit]No. 21 Maintenance Unit RAF Bomb Storage dump was constructed in disused underground gypsum mine workings. The tunnels were used to store a variety of ordnance, bombs and explosives used by the Royal Air Force; in addition to shells and bombs, it also held up to 500 million rounds of small arms ammunition.[6] At 11:15 hours on 27 November 1944, two explosions occurred within the ordnance storage depot. Up to 4,000 tonnes (4,400 tons) of explosives detonated prematurely, including 3,500 tonnes (3,900 tons) of high explosive bombs.[5][3] It left a crater 300 yards (270 m) by 233 yards (213 m) in length and 100 feet (30 m) deep, covering 12 acres (4.9 ha).[4][5][3]

Eyewitnesses reported seeing two distinct columns of black smoke in the form of a mushroom cloud ascending several thousand feet, and a blaze at the foot of each column. According to the commanding officer of 21 M.U., Group Captain Storrar, an open dump of incendiary bombs caught fire but it was allowed to burn itself out without damage or casualties.[4][5][3]

All property within a radius of 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) of the crater was completely or significantly damaged.[7] Upper Castle Hayes Farm was completely destroyed. The Peter Ford & Sons lime and gypsum works to the north of the village and Purse cottages were obliterated. The lime works was also flooded when the explosion destroyed the reservoir dam. Hanbury Fields Farm, Hare Holes Farm and also Croft Farm with adjacent cottages were all extensively damaged. Debris also damaged Hanbury village.[4][5][3]

Casualties

[edit]At the time, no precise records were kept monitoring the exact number of workers at the facility. While the exact death toll is uncertain as a result of this, at least 70 people are believed to have died in the explosion. The official report stated that 90 were killed, missing or injured,[7][8] including:

- 26 killed or missing at the RAF dump—divided between RAF personnel, civilian workers and some Italian prisoners of war who were working there—5 of whom were gassed by toxic fumes; 10 were also severely injured. Six are buried in military graves.[3]

- 37 killed (drowned) or missing at Peter Ford & Sons gypsum mine and plaster mill, and surrounding countryside; 12 also injured.

- Approximately 7 farm workers at the nearby Upper Castle Hayes Farm.

- One diver was killed during search and rescue operations.[3]

Two hundred cattle were also killed by the explosion. Some live cattle were removed from the vicinity, but were found dead the following morning.[7]

The inscription on the memorial stone that was erected at the crater in November 1990, lists 70 names of people who died as a result of the explosion. 18 of these names are people who are still missing and presumed dead. A relief fund organised by the local people made payments to victims and their families until 1959.[6]

Investigation

[edit]

The cause of the disaster was not made public at the time. As it was during the Second World War, the British government did not want Nazi Germany or the Empire of Japan to know the extent of the disaster. A secret investigation concluded that a variety of factors and circumstances had contributed to the cause.[1]

There had been staff shortages, a management position had remained empty for a year, and 189 inexperienced Italian prisoners of war were working in the mines at the time of the accident. There were also equipment shortages, a lack of training for the workers, multiple agencies in the mine resulted in a lack of an organised chain of command, and pressure from British government and military to increase work rate for the war effort resulted in safety regulations being often overlooked.[1]

It was not until 1974, that the report was publicly released. The explosion was probably caused by a site worker removing a detonator from a live bomb using a brass chisel, rather than a wooden batten, resulting in sparks. An eyewitness testified that he had seen workers using brass chisels, in direct contravention of safety regulations.[9]

Aftermath

[edit]

Although much of the storage facility was annihilated by the explosion, the site continued to be used by the RAF for munitions storage until 1966, when No. 21 Maintenance Unit was disbanded.[2] Following France's withdrawal from NATO's integrated military structure in 1966,[10] the site was used by the United States Army between 1967 and 1973 to store US ammunition previously stored in France.[2]

By 1979, RAF Fauld had been closed and fenced off. The area is now covered with over 150 species of trees and wildlife. Access is restricted as a significant amount of explosive ordnance remains buried in the site. The UK government has deemed its removal too expensive to be feasible.[11]

Memorial

[edit]

On 13 September 1990, 46 years after the initial incident, it was announced that a memorial stone was to be erected to commemorate those who died, to be paid for by the public, as Hanbury Parish Council did not have the necessary funds. The stone used for the memorial was donated by the Italian government and flown to the United Kingdom on an RAF plane.[12] It was unveiled on 25 November 1990.[13]

A second memorial was dedicated on the 70th anniversary of the explosion, 27 November 2014. A tourist trail leads to the crater from the Cock Inn pub in Hanbury, which was damaged by debris from the explosion.[14]

The maintenance unit was the subject of several paintings under the collective title "The Bomb Store" by David Bomberg, who was briefly employed as a war artist by the War Ministry in 1943.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Hardy, Valerie (2019). Voices From The Explosion. Second Edition - Woldscot. ISBN 978-1-5272-2969-3.

- ^ a b c Reed, John (1977). "Largest Wartime Explosions: 21 Maintenance Unit, RAF Fauld, Staff. November 27, 1944". After the Battle. No. 18. Essex: Battle of Britain International Limited. pp. 35–40. ISSN 0306-154X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goddard, Jane (6 October 2014). "Bygones: Book coincides with 70th anniversary of giant explosion at RAF Fauld, near Burton". Derby Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d Rowe, Mark (29 August 2008). "World's largest-ever explosion (almost)". BBC Stoke. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Waltham, Tony (2001). "Landmark of geology in the East Midlands: The explosion crater at Fauld" (PDF). Mercian Geologist. 15 (2): 123-125. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ a b "The Fauld Explosion". Tutbury: Local history and information. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Ministry of Home Security report File RE. 5/5i region IX.

- ^ "Archival material relating to AIR 17/10 (prev. RE5/5/76)". UK National Archives.

- ^ "WW2 People's War – War Memories – with a song and dance and a huge explosion". BBC. 24 October 2005. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ "Member countries". NATO. 9 July 2009. Archived from the original on 6 January 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Bell, David (2005). "8". Staffordshire Tales of Murder & Mystery. Countryside Books. p. 78. ISBN 1-85306-922-1.

- ^ "Blast memorial go-ahead after long campaign". Staffordshire Sentinel. 13 September 1990. Retrieved 13 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "War Memorials Register: Fauld Crater Memorial". Imperial War Museums. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Fauld explosion 70th anniversary: New memorial unveiled". BBC News. 27 November 2014. Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ Cork, Richard (1986). David Bomberg. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300038279.

Further reading

[edit]- "Britain's big bang" by Peter Grego, Astronomy Now, November 2004. ISSN 0951-9726.

- McCamley, N.J. (1998). Secret Underground Cities. Barnsley: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-585-3.

- McCamley, N.J. (2004). Disasters Underground. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-022-4.

- Grid Reference: SK182277

- Hardy, Valerie. (2015). Voices from the Explosion: RAF Fauld, the World's Largest Accidental Blast, 1944. Dark River. ISBN 978-1-911121-03-9

- McCamley, N.J. (2015). The Fauld Disaster 27 November 1944. Monkton Farleigh: Folly Books. ISBN 978-0-9928554-3-7