Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

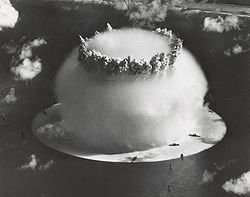

Mushroom cloud

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2025) |

A mushroom cloud is a distinctive mushroom-shaped flammagenitus cloud of debris, smoke, and usually condensed water vapour resulting from a large explosion. The effect is most commonly associated with a nuclear explosion, but any sufficiently energetic detonation or deflagration will produce a similar effect. They can be caused by powerful conventional weapons, including large thermobaric weapons. Some volcanic eruptions and impact events can produce natural mushroom clouds.

Mushroom clouds result from the sudden formation of a large volume of lower-density gases at any altitude, causing a Rayleigh–Taylor instability. The buoyant mass of gas rises rapidly, resulting in turbulent vortices curling downward around its edges, forming a temporary vortex ring that draws up a central column, possibly with smoke, debris, condensed water vapor, or a combination of these, to form the "mushroom stem". The mass of gas plus entrained moist air eventually reaches an altitude where it is no longer of lower density than the surrounding air; at this point, it disperses, drifting back down, which results in fallout following a nuclear blast. The stabilization altitude depends strongly on the profiles of the temperature, dew point, and wind shear in the air at and above the starting altitude.

Early accounts and origins of term

[edit]

Although the term appears to have been coined in the early 1950s, mushroom clouds generated by explosions were being described centuries before the Atomic Age. A contemporary aquatint by an unknown artist of the 1782 Franco-Spanish attack on Gibraltar shows one of the attacking force's floating batteries exploding with a mushroom cloud after the British defenders set it ablaze by firing heated shot.

In 1798, Gerhard Vieth published a detailed and illustrated account of a cloud in the neighborhood of Gotha that was "not unlike a mushroom in shape". The cloud had been observed by legation counselor Lichtenberg a few years earlier on a warm summer afternoon. It was interpreted as an irregular meteorological cloud and seemed to have caused a storm with rain and thunder from a new dark cloud that developed beneath it. Lichtenberg stated to have later observed somewhat similar clouds, but none as remarkable.[1]

The 1917 Halifax Explosion produced a mushroom cloud. In 1930 Olaf Stapledon in his novel Last and First Men imagines the first demonstration of an atomic weapon "clouds of steam from the boiling sea.. a gigantic mushroom of steam and debris". The Times published a report on 1 October 1937 of a Japanese attack on Shanghai, China, that generated "a great mushroom of smoke". During World War II, the destruction of the Japanese battleship Yamato produced a mushroom cloud.[2]

The atomic bomb cloud over Nagasaki, Japan, was described in The Times of London of 13 August 1945 as a "huge mushroom of smoke and dust".[citation needed] On 9 September 1945, The New York Times published an eyewitness account of the Nagasaki bombing, written by William L. Laurence, the official newspaper correspondent of the Manhattan Project, who accompanied one of the three aircraft that made the bombing run. He wrote of the bomb producing a "pillar of purple fire" out of the top of which came "a giant mushroom that increased the height of the pillar to a total of 45,000 feet".[3]

In 1946, the Operation Crossroads nuclear bomb tests were described as having a "cauliflower" cloud, but a reporter present also spoke of "the mushroom, now the common symbol of the atomic age". Mushrooms have traditionally been associated both with life and death, food and poison, which made them a more powerful symbolic connection than, say, the "cauliflower" cloud.[4]

Physics

[edit]

Mushroom clouds are formed by many sorts of large explosions under Earth's gravity, but they are best known for their appearance after nuclear detonations. Without gravity, or without a thick atmosphere, the explosive's by-product gases would remain spherical. Nuclear weapons are usually detonated above the ground (not upon impact, because some of the energy would be dissipated by the ground motions), to maximize the effect of their spherically expanding fireball and blast wave. Immediately after the detonation, the fireball begins to rise into the air, acting on the same principle as a hot-air balloon.

One way to analyze the motion, once the hot gas has cleared the ground sufficiently, is as a "spherical cap bubble",[5] as this gives agreement between the rate of rise and observed diameter.

As it rises, a Rayleigh–Taylor instability is formed, and air is drawn upwards and into the cloud (similar to the updraft of a chimney), producing strong air currents known as "afterwinds", while, inside the head of the cloud, the hot gases rotate in a toroidal shape. When the detonation altitude is low enough, these afterwinds will draw in dirt and debris from the ground below to form the stem of the mushroom cloud.

Once the mass of hot gases reaches its equilibrium level, the ascent stops, and the cloud begins to flatten into the characteristic mushroom shape, often assisted by surface growth from decaying turbulence.

Nuclear detonations

[edit]Description

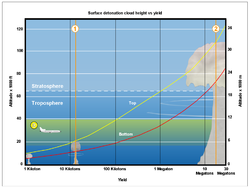

[edit]At the moment of a nuclear explosion, a fireball is formed. The ascending, roughly spherical mass of hot, incandescent gases changes shape due to atmospheric friction, and the surface of the fireball is cooled by energy radiation, turning from a sphere to a violently rotating spheroidal vortex. A Rayleigh–Taylor instability is formed as the cool air underneath initially pushes the bottom fireball gases into an inverted cup shape. This causes turbulence and a vortex that sucks more air into the center, creating external afterwinds and further cooling the fireball. The speed of rotation slows as the fireball cools and may stop entirely during later phases. The vaporized parts of the weapon and ionized air cool into visible gases, forming a cloud; the white-hot vortex core becomes yellow, then dark red, then loses visible incandescence. With further cooling, the bulk of the cloud fills in as atmospheric moisture condenses. As the cloud ascends and cools, its buoyancy lessens, and its ascent slows. If the size of the fireball is comparable to the atmospheric density scale height, the whole cloud rise will be ballistic, overshooting a large volume of overdense air to greater altitudes than the final stabilization altitude. Significantly smaller fireballs produce clouds with buoyancy-governed ascent.

After reaching the tropopause (the bottom of the region of strong static stability) the cloud tends to slow and spread out. If it contains sufficient energy, the central part may continue rising up into the stratosphere as an analog of a standard thunderstorm.[6] A mass of air ascending from the troposphere to the stratosphere leads to the formation of acoustic gravity waves, virtually identical to those created by intense stratosphere-penetrating thunderstorms. Smaller-scale explosions penetrating the tropopause generate waves of higher frequency, classified as infrasound. The explosion raises a large amount of moisture-laden air from lower altitudes. As the air rises, its temperature drops and its water vapour first condenses as water droplets and later freezes as ice crystals. The phase change releases latent heat, heating the cloud and driving it to yet higher altitudes. The heads of the clouds consist of highly radioactive particles, primarily the fission products and other weapon debris aerosols, and are usually dispersed by the wind, though weather patterns (especially rain) can produce nuclear fallout.[7] The droplets of condensed water gradually evaporate, leading to the cloud's apparent disappearance. The radioactive particles, however, remain suspended in the air, and the invisible cloud continues depositing fallout along its path.

A mushroom cloud undergoes several phases of formation.[8]

- Early time, the first ~20 seconds, when the fireball forms and the fission products mix with the material aspired from the ground or ejected from the crater. The condensation of evaporated ground occurs in first few seconds, most intensely during fireball temperatures between 3500 and 4100 K.[9]

- Rise and stabilization phase, 20 seconds to 10 minutes, when the hot gases rise up and early large fallout is deposited.

- Late time, until about 2 days later, when the airborne particles are being distributed by wind, deposited by gravity, and scavenged by precipitation.

The shape of the cloud is influenced by the local atmospheric conditions and wind patterns. The fallout distribution is predominantly a downwind plume. However, if the cloud reaches the tropopause, it may spread against the wind, because its convection speed is higher than the ambient wind speed. At the tropopause, the cloud shape is roughly circular and spread out. The initial color of some radioactive clouds can be colored red or reddish-brown, due to presence of nitrogen dioxide and nitric acid, formed from initially ionized nitrogen, oxygen, and atmospheric moisture. In the high-temperature, high-radiation environment of the blast, ozone is also formed. It is estimated that each megaton of yield produces about 5,000 tons of nitrogen oxides.[10] A higher-yield detonation can carry the nitrogen oxides from the burst high enough in atmosphere to cause significant depletion of the ozone layer. Yellow and orange hues have also been described. This reddish hue is later obscured by the white colour of water/ice clouds, condensing out of the fast-flowing air as the fireball cools, and the dark colour of smoke and debris sucked into the updraft. The ozone gives the blast its characteristic corona discharge-like smell.[11]

The distribution of radiation in the mushroom cloud varies with the yield of the explosion, type of weapon, fusion–fission ratio, burst altitude, terrain type, and weather. In general, lower-yield explosions have about 90% of their radioactivity in the mushroom head and 10% in the stem. In contrast, megaton-range explosions tend to have most of their radioactivity in the lower third of the mushroom cloud. The fallout may appear as dry, ash-like flakes, or as particles too small to be visible; in the latter case, the particles are often deposited by rain. Large amounts of newer, more radioactive particles deposited on skin can cause beta burns, often presenting as discolored spots and lesions on the backs of exposed animals.[13] The fallout from the Castle Bravo test had the appearance of white dust and was nicknamed Bikini snow; the tiny white flakes resembled snowflakes, stuck to surfaces, and had a salty taste. In Operation Wigwam, 41.4% of the fallout consisted of irregular opaque particles, slightly over 25% of particles with transparent and opaque areas, approximately 20% of microscopic marine organisms, and 2% of microscopic radioactive threads of unknown origin.[14]

Differences with detonation types

[edit]With surface and near-surface air bursts, the amount of debris lofted into the air decreases rapidly with increasing burst altitude. At a burst altitude of approximately 7 meters/kiloton1⁄3, a crater is not formed, and correspondingly lower amounts of dust and debris are produced. The fallout-reducing height, above which the primary radioactive particles consist mainly of the fine fireball condensation, is approximately 55 meters/kiloton0.4.[7] However, even at these burst altitudes, fallout may be formed by other mechanisms. Airbursts produce white, steamy stems, while surface bursts produce gray to brown stems because large amounts of dust, dirt, soil, and debris are sucked into the mushroom cloud. Surface bursts produce dark mushroom clouds containing irradiated material from the ground in addition to the bomb and its casing and therefore produce more radioactive fallout, with larger particles that readily deposit locally.

A detonation high above the ground may produce a mushroom cloud without a stem. A double mushroom, with two levels, can be formed under certain conditions. For example, the Buster-Jangle Sugar shot formed the first head from the blast, followed by another one generated by the heat from the hot, freshly formed crater.[14]

A detonation significantly below ground level or deep below the water (for instance, a nuclear depth charge) does not produce a mushroom cloud, as the explosion causes the vaporization of a huge amount of earth or water, creating a bubble which then collapses in on itself; in the case of a less deep underground explosion, this produces a subsidence crater. An underwater detonation near the surface may produce a pillar of water which collapses to form a cauliflower-like shape, which is easily mistaken for a mushroom cloud (such as in the well-known pictures of the Crossroads Baker test). An underground detonation at low depth produces a mushroom cloud and a base surge, two different distinct clouds. The amount of radiation vented into the atmosphere decreases rapidly with increasing detonation depth.

Cloud composition

[edit]

The cloud contains three main classes of material: the remains of the weapon and its fission products, the material acquired from the ground (only significant for burst altitudes below the fallout-reducing altitude, which depends on the weapon yield), and water vapour. The bulk of the radiation contained in the cloud consists of the nuclear fission products; neutron activation products from the weapon materials, air, and the ground debris form only a minor fraction. Neutron activation starts during the neutron burst at the instant of the blast, and the range of this neutron burst is limited by the absorption of the neutrons as they pass through the Earth's atmosphere.

Thermonuclear weapons produce a significant part of their yield from nuclear fusion. Fusion products are typically non-radioactive. The degree of radiation fallout production is therefore measured in kilotons of fission. The Tsar Bomba, which produced 97% of its 50-megaton yield from fusion, was a very clean weapon compared to what would typically be expected of a weapon of its yield (although it still produced 1.5 megatons of its yield from fission), as its fusion tamper was made of lead instead of uranium-238; otherwise, its yield would have been 100 megatons with 51 megatons produced from fission. Were it to be detonated at or near the surface, its fallout would comprise fully one-quarter of all the fallout from every nuclear weapon test, combined.

Initially, the fireball contains a highly ionized plasma consisting only of atoms of the weapon, its fission products, and atmospheric gases of adjacent air. As the plasma cools, the atoms react, forming fine droplets and then solid particles of oxides. The particles coalesce to larger ones, and deposit on surface of other particles. Larger particles usually originate from material aspired into the cloud. Particles aspired while the cloud is still hot enough to melt them mix with the fission products throughout their volume. Larger particles get molten radioactive materials deposited on their surface. Particles aspired into the cloud later, when its temperature is low enough, do not become significantly contaminated. Particles formed only from the weapon are fine enough to stay airborne for a long time and become widely dispersed and diluted to non-hazardous levels. Higher-altitude blasts which do not aspire ground debris, or which aspire dust only after cooling enough and where the radioactive fraction of the particles is therefore small, cause a much smaller degree of localized fallout than lower-altitude blasts with larger radioactive particles formed.

The concentration of condensation products is the same for the small particles and for the deposited surface layers of larger particles. About 100 kg of small particles are formed per kiloton of yield. The volume, and therefore activity, of the small particles is almost three orders of magnitude lower than the volume of the deposited surface layers on larger particles. For higher-altitude blasts, the primary particle forming processes are condensation and subsequent coagulation. For lower-altitude and ground blasts, with involvement of soil particles, the primary process is deposition on the foreign particles.

A low-altitude detonation produces a cloud with a dust loading of 100 tons per megaton of yield. A ground detonation produces clouds with about three times as much dust. For a ground detonation, approximately 200 tons of soil per kiloton of yield is melted and comes in contact with radiation.[9] The fireball volume is the same for a surface or an atmospheric detonation. In the first case, the fireball is a hemisphere instead of a sphere, with a correspondingly larger radius.[9]

The particle sizes range from submicrometer- and micrometer-sized (created by condensation of plasma in the fireball), through 10–500 micrometers (surface material agitated by the blast wave and raised by the afterwinds), to millimeter and above (crater ejecta). The size of particles together with the altitude they are carried to, determines the length of their stay in the atmosphere, as larger particles are subject to dry precipitation. Smaller particles can be also scavenged by precipitation, either from the moisture condensing in the cloud or from the cloud intersecting with a rain cloud. The fallout carried down by rain is known as rain-out if scavenged during raincloud formation, washout if absorbed into already formed falling raindrops.[15]

Particles from air bursts are smaller than 10–25 micrometers, usually in the submicrometer range. They are composed mostly of iron oxides, with smaller proportion of aluminium oxide, and uranium and plutonium oxides. Particles larger than 1–2 micrometers are very spherical, corresponding to vaporized material condensing into droplets and then solidifying. The radioactivity is evenly distributed throughout the particle volume, making total activity of the particles linearly dependent on particle volume.[9] About 80% of activity is present in more volatile elements, which condense only after the fireball cools to considerable degree. For example, strontium-90 will have less time to condense and coalesce into larger particles, resulting in greater degree of mixing in the volume of air and smaller particles.[16] The particles produced immediately after the burst are small, with 90% of the radioactivity present in particles smaller than 300 nanometers. These coagulate with stratospheric aerosols. Coagulation is more extensive in the troposphere, and, at ground level, most activity is present in particles between 300 nm and 1 μm. The coagulation offsets the fractionation processes at particle formation, evening out isotopic distribution.

For ground and low-altitude bursts, the cloud contains vaporized, melted and fused soil particles. The distribution of activity through the particles depends on their formation. Particles formed by vaporization-condensation have activity evenly distributed through volume as the air-burst particles. Larger molten particles have the fission products diffused through the outer layers, and fused and non-melted particles that were not heated sufficiently but came in contact with the vaporized material or scavenged droplets before their solidification have a relatively thin layer of high activity material deposited on their surface. The composition of such particles depends on the character of the soil, usually a glass-like material formed from silicate minerals. The particle sizes do not depend on the yield but instead on the soil character, as they are based on individual grains of the soil or their clusters. Two types of particles are present, spherical, formed by complete vaporization-condensation or at least melting of the soil, with activity distributed evenly through the volume (or with a 10–30% volume of inactive core for larger particles between 0.5–2 mm), and irregular-shaped particles formed at the edges of the fireball by fusion of soil particles, with activity deposited in a thin surface layer. The amount of large irregular particles is insignificant.[9] Particles formed from detonations above, or in, the ocean, will contain short-lived radioactive sodium isotopes, and salts from the sea water. Molten silica is a very good solvent for metal oxides and scavenges small particles easily; explosions above silica-containing soils will produce particles with isotopes mixed through their volume. In contrast, coral debris, based on calcium carbonate, tends to adsorb radioactive particles on its surface.[16]

The elements undergo fractionation during particle formation, due to their different volatility. Refractory elements (Sr, Y, Zr, Nb, Ba, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Pm) form oxides with high boiling points; these precipitate the fastest and at the time of particle solidification, at temperature of 1400 °C, are considered to be fully condensed. Volatile elements (Kr, Xe, I, Br) are not condensed at that temperature. Intermediate elements have their (or their oxides) boiling points close to the solidification temperature of the particles (Rb, Cs, Mo, Ru, Rh, Tc, Sb, Te). The elements in the fireball are present as oxides, unless the temperature is above the decomposition temperature of a given oxide. Less refractory products condense on surfaces of solidified particles. Isotopes with gaseous precursors solidify on the surface of the particles as they are produced by decay.

The largest and therefore most radioactive particles are deposited by fallout in the first few hours after the blast. Smaller particles are carried to higher altitudes and descend more slowly, reaching ground in a less radioactive state as the isotopes with the shortest half-lives decay the fastest. The smallest particles can reach the stratosphere and stay there for weeks, months, or even years, and cover an entire hemisphere of the planet via atmospheric currents. The higher danger, short-term, localized fallout is deposited primarily downwind from the blast site, in a cigar-shaped area, assuming a wind of constant strength and direction. Crosswinds, changes in wind direction, and precipitation are factors that can greatly alter the fallout pattern.[17]

The condensation of water droplets in the mushroom cloud depends on the amount of condensation nuclei. Too many condensation nuclei actually inhibit condensation, as the particles compete for a relatively insufficient amount of water vapor. Chemical reactivity of the elements and their oxides, ion adsorption properties, and compound solubility influence particle distribution in the environment after deposition from the atmosphere. Bioaccumulation influences the propagation of fallout radioisotopes in the biosphere.

Radioisotopes

[edit]The primary fallout hazard is gamma radiation from short-lived radioisotopes, which represent the bulk of activity. Within 24 hours after a burst, the fallout gamma radiation level drops 60 times. Longer-life radioisotopes, typically caesium-137 and strontium-90, present a long-term hazard. Intense beta radiation from the fallout particles can cause beta burns to people and animals coming in contact with the fallout shortly after the blast. Ingested or inhaled particles cause an internal dose of alpha and beta radiation, which may lead to long-term effects, including cancer. The neutron irradiation of the atmosphere produces a small amount of activation, mainly as long-lived carbon-14 and short-lived argon-41. The elements most important for induced radioactivity for sea water are sodium-24, chlorine, magnesium, and bromine. For ground bursts, the elements of concern are aluminium-28, silicon-31, sodium-24, manganese-56, iron-59, and cobalt-60.

The bomb casing can be a significant sources of neutron-activated radioisotopes. The neutron flux in the bombs, especially thermonuclear devices, is sufficient for high-threshold nuclear reactions. The induced isotopes include cobalt-60, 57 and 58, iron-59 and 55, manganese-54, zinc-65, yttrium-88, and possibly nickel-58 and 62, niobium-63, holmium-165, iridium-191, and short-lived manganese-56, sodium-24, silicon-31, and aluminium-28. Europium-152 and 154 can be present, as well as two nuclear isomers of rhodium-102. During the Operation Hardtack, tungsten-185, 181 and 187 and rhenium-188 were produced from elements added as tracers to the bomb casings, to allow identification of fallout produced by specific explosions. Antimony-124, cadmium-109, and cadmium-113m are also mentioned as tracers.[9]

The most significant radiation sources are the fission products from the primary fission stage, and in the case of fission-fusion-fission weapons, from the fission of the fusion stage uranium tamper. Many more neutrons per unit of energy are released in a thermonuclear explosion in comparison with a purely fission yield influencing the fission products composition. For example, uranium-237 is a unique thermonuclear explosion marker, as it is produced by a (n,2n) reaction from uranium-238, with the minimal neutron energy needed being about 5.9 MeV. Considerable amounts of neptunium-239 and uranium-237 are indicators of a fission-fusion-fission explosion. Minor amounts of uranium-240 are also formed, and capture of large numbers of neutrons by individual nuclei leads to formation of small but detectable amounts of higher transuranium elements, e.g. einsteinium-255 and fermium-255.[9]

One of the important fission products is krypton-90, a radioactive noble gas. It diffuses easily in the cloud and undergoes two decays to rubidium-90 and then strontium-90, with half-lives of 33 seconds and 3 minutes. The noble gas nonreactivity and rapid diffusion is responsible for depletion of local fallout in Sr-90, and corresponding Sr-90 enrichment of remote fallout.[18]

The radioactivity of the particles decreases with time, with different isotopes being significant at different timespans. For soil activation products, aluminium-28 is the most important contributor during the first 15 minutes. Manganese-56 and sodium-24 follow until about 200 hours. Iron-59 follows at 300 hours, and after 100–300 days, the significant contributor becomes cobalt-60.

Radioactive particles can be carried for considerable distances. Radiation from the Trinity test was washed out by a rainstorm in Illinois. This was deduced, and the origin traced, when Eastman Kodak found x-ray films were being fogged by cardboard packaging produced in the Midwest. Unanticipated winds carried lethal doses of Castle Bravo fallout over the Rongelap Atoll, forcing its evacuation. The crew of Daigo Fukuryu Maru, a Japanese fishing boat located outside of the predicted danger zone, was also affected. Strontium-90 found in worldwide fallout later led to the Partial Test Ban Treaty.[16]

Fluorescent glow

[edit]The intense radiation in the first seconds after the blast may cause an observable aura of fluorescence, the blue-violet-purple glow of ionized oxygen and nitrogen out to a significant distance from the fireball, surrounding the head of the forming mushroom cloud.[19][20][21] This light is most easily visible at night or under conditions of weak daylight.[7] The brightness of the glow decreases rapidly with elapsed time since the detonation, becoming only barely visible after a few tens of seconds.[22]

Condensation effects

[edit]Nuclear mushroom clouds are often accompanied by short-lived vapour clouds, known variously as "Wilson clouds", condensation clouds, or vapor rings. The "negative phase" following the positive overpressure behind a shock front causes a sudden rarefaction of the surrounding medium. This low pressure region causes an adiabatic drop in temperature, causing moisture in the air to condense in an outward moving shell surrounding the explosion. When the pressure and temperature return to normal, the Wilson cloud dissipates.[23] Scientists observing the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests in 1946 at Bikini Atoll named that transitory cloud a "Wilson cloud" because of its visual similarity to a Wilson cloud chamber; the cloud chamber uses condensation from a rapid pressure drop to mark the tracks of electrically charged subatomic particles. Analysts of later nuclear bomb tests used the more general term "condensation cloud" in preference to "Wilson cloud".

The same kind of condensation is sometimes seen above the wings of jet aircraft at low altitude in high-humidity conditions. The top of a wing is a curved surface. The curvature (and increased air velocity) causes a reduction in air pressure, as given by Bernoulli's Law. This reduction in air pressure causes cooling, and when the air cools past its dew point, water vapour condenses out of the air, producing droplets of water, which become visible as a white cloud. In technical terms, the "Wilson cloud" is also an example of the Prandtl–Glauert singularity in aerodynamics.[citation needed]

The shape of the shock wave is influenced by variation of the speed of sound with altitude, and the temperature and humidity of different atmospheric layers determines the appearance of the Wilson clouds. Condensation rings around or above the fireball are a commonly observed feature. Rings around the fireball may become stable, becoming rings around the rising stem. Higher-yield explosions cause intense updrafts, where air speeds can reach 300 miles per hour (480 km/h). The entrainment of higher-humidity air, combined with the associated drop in pressure and temperature, leads to the formation of skirts and bells around the stem. If the water droplets become sufficiently large, the cloud structure they form may become heavy enough to descend; in this way, a rising stem with a descending bell around it can be produced. Layering of humidity in the atmosphere, responsible for the appearance of the condensation rings as opposed to a spherical cloud, also influences the shape of the condensation artifacts along the stem of the mushroom cloud, as the updraft causes laminar flow. The same effect above the top of the cloud, where the expansion of the rising cloud pushes a layer of warm, humid, low-altitude air upwards into cold, high-altitude air, first causes the condensation of water vapour out of the air and then causes the resulting droplets to freeze, forming ice caps (or icecaps), similar in both appearance and mechanism of formation to scarf clouds.

The resulting composite structures can become very complex. The Castle Bravo cloud had, at various phases of its development, 4 condensation rings, 3 ice caps, 2 skirts, and 3 bells.

-

The mushroom cloud from the 15-megaton Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test, showing multiple condensation rings, 1 March 1954

-

The mushroom cloud from the 11-megaton Castle Romeo hydrogen bomb test, showing a prominent condensation ring

-

The mushroom cloud from the 6.9-megaton Castle Union hydrogen bomb test, showing multiple condensation rings

-

The water column from the 21-kiloton Crossroads Baker test, involving a nuclear underwater explosion, showing a prominent, spherical Wilson cloud

-

The mushroom cloud from the 225-kiloton Greenhouse George test, showing a well-developed bell

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "MDZ-Reader | Band | Physikalischer Kinderfreund / Vieth, Gerhard Ulrich Anton | Physikalischer Kinderfreund / Vieth, Gerhard Ulrich Anton". reader.digitale-sammlungen.de.

- ^ Reynolds, Clark G (1982). The Carrier War. Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-8094-3304-9. p. 169.

- ^ Eyewitness Account of Atomic Bomb Over Nagasaki Archived 2011-01-06 at the Wayback Machine hiroshima-remembered.com. Retrieved on 2010-08-09.

- ^ Weart, Spencer (1987). Nuclear Fear: A History of Images. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62836-6. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016.

- ^ Batchelor, G. K. (2000). "6.11, Large Gas Bubbles in Liquid". An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 470. ISBN 978-0-521-66396-0. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016.

- ^ "The Mushroom Cloud". Atomic Archive. Archived from the original on 30 August 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Glasstone and Dolan 1977

- ^ National Research Council; Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences; Committee on the Effects of Nuclear Earth-Penetrator and Other Weapons (2005). Effects of Nuclear Earth-Penetrator and Other Weapons. National Academies Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-309-09673-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Radioactive fallout after nuclear explosions and accidents, Volume 3, I. A. Izraėl, Elsevier, 2002 ISBN 0080438555

- ^ Effects of Nuclear Explosions Archived 2014-04-28 at the Wayback Machine. Nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved on 2010-02-08.

- ^ Key Issues: Nuclear Weapons: History: Pre Cold War: Manhattan Project: Trinity: Eyewitness Philip Morrison Archived 2014-07-21 at the Wayback Machine. Nuclearfiles.org (1945-07-16). Retrieved on 2010-02-08.

- ^ The Mushroom Cloud, by Virginia L. Snitow

- ^ Thomas Carlyle Jones; Ronald Duncan Hunt; Norval W. King (1997). Veterinary Pathology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 690. ISBN 978-0-683-04481-2.

- ^ a b Richard Lee Miller (1986). Under the Cloud: The Decades of Nuclear Testing. Two-Sixty Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-02-921620-0.

- ^ Constantin Papastefanou (2008). Radioactive Aerosols. Elsevier. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-08-044075-0.

- ^ a b c Lawrence Badash (2009). A Nuclear Winter's Tale: Science and Politics in the 1980s. MIT Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-262-25799-2.

- ^ Robert Ehrlich (1985). Waging Nuclear Peace: The Technology and Politics of Nuclear Weapons. SUNY Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-87395-919-3.

- ^ Ralph E. Lapp (October 1956) "Strontium limits in peace and war", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 12 (8): 287–289, 320.

- ^ "The Legacy of Trinity". ABQ Journal. 28 October 1999. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ Nobles, Ralph (December 2008). "The Night the World Changed: The Trinity Nuclear Test" (PDF). Los Alamos Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ Feynman, Richard (21 May 2005). "'This is how science is done'". Dimaggio.org. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ Borst, Lyle B. (April 1953). "Nevada Weapons Test". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 9 (3). Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc.: 74. Bibcode:1953BuAtS...9c..73B. doi:10.1080/00963402.1953.11457386. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ^ Glasstone and Dolan 1977, p. 631

Bibliography

[edit]- Glasstone, Samuel, and Dolan, Philip J. The Effects of Nuclear Weapons 3rd edn. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Defense and Energy Research and Development Administration, 1977. (esp. "Chronological development of an air-burst" and "Description of Air and Surface Bursts" in Chapter II)

- Vigh, Jonathan. Mechanisms by Which the Atmosphere Adjusts to an Extremely Large Explosive Event, 2001.

External links

[edit]- Carey Sublette's Nuclear Weapon Archive has many photographs of mushroom clouds

- DOE Nevada Site Office has many photographs of nuclear tests conducted at the Nevada Test Site and elsewhere

- Burning bulbs is a set of photographs by Kevin Tieskoetter, showing fine mushroom cloud structures generated by burning lightbulb filaments in air