Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Regular language

View on WikipediaIn theoretical computer science and formal language theory, a regular language (also called a rational language)[1][2] is a formal language that can be defined by a regular expression, in the strict sense in theoretical computer science (as opposed to many modern regular expression engines, which are augmented with features that allow the recognition of non-regular languages).

Alternatively, a regular language can be defined as a language recognised by a finite automaton. The equivalence of regular expressions and finite automata is known as Kleene's theorem[3] (after American mathematician Stephen Cole Kleene). In the Chomsky hierarchy, regular languages are the languages generated by Type-3 grammars.

Formal definition

[edit]The collection of regular languages over an alphabet Σ is defined recursively as follows:

- The empty language ∅ is a regular language.

- For each a ∈ Σ (a belongs to Σ), the singleton language {a} is a regular language.

- If A is a regular language, A* (Kleene star) is a regular language. Due to this, the empty string language {ε} is also regular.

- If A and B are regular languages, then A ∪ B (union) and A • B (concatenation) are regular languages.

- No other languages over Σ are regular.

See Regular expression § Formal language theory for syntax and semantics of regular expressions.

Examples

[edit]All finite languages are regular; in particular the empty string language {ε} = ∅* is regular. Other typical examples include the language consisting of all strings over the alphabet {a, b} which contain an even number of as, or the language consisting of all strings of the form: several as followed by several bs.

A simple example of a language that is not regular is the set of strings {anbn | n ≥ 0}.[4] Intuitively, it cannot be recognized with a finite automaton, since a finite automaton has finite memory and it cannot remember the exact number of a's. Techniques to prove this fact rigorously are given below.

Equivalent formalisms

[edit]A regular language satisfies the following equivalent properties:

- it is the language of a regular expression (by the above definition)

- it is the language accepted by a nondeterministic finite automaton (NFA)[note 1][note 2]

- it is the language accepted by a deterministic finite automaton (DFA)[note 3][note 4]

- it can be generated by a regular grammar[note 5][note 6]

- it is the language accepted by an alternating finite automaton

- it is the language accepted by a two-way finite automaton

- it can be generated by a prefix grammar

- it can be accepted by a read-only Turing machine

- it can be defined in monadic second-order logic (Büchi–Elgot–Trakhtenbrot theorem)[5]

- it is recognized by some finite syntactic monoid M, meaning it is the preimage {w ∈ Σ* | f(w) ∈ S} of a subset S of a finite monoid M under a monoid homomorphism f : Σ* → M from the free monoid on its alphabet[note 7]

- the number of equivalence classes of its syntactic congruence is finite.[note 8][note 9] (This number equals the number of states of the minimal deterministic finite automaton accepting L.)

Properties 10. and 11. are purely algebraic approaches to define regular languages; a similar set of statements can be formulated for a monoid M ⊆ Σ*. In this case, equivalence over M leads to the concept of a recognizable language.

Some authors use one of the above properties different from "1." as an alternative definition of regular languages.

Some of the equivalences above, particularly those among the first four formalisms, are called Kleene's theorem in textbooks. Precisely which one (or which subset) is called such varies between authors. One textbook calls the equivalence of regular expressions and NFAs ("1." and "2." above) "Kleene's theorem".[6] Another textbook calls the equivalence of regular expressions and DFAs ("1." and "3." above) "Kleene's theorem".[7] Two other textbooks first prove the expressive equivalence of NFAs and DFAs ("2." and "3.") and then state "Kleene's theorem" as the equivalence between regular expressions and finite automata (the latter said to describe "recognizable languages").[2][8] A linguistically oriented text first equates regular grammars ("4." above) with DFAs and NFAs, calls the languages generated by (any of) these "regular", after which it introduces regular expressions which it terms to describe "rational languages", and finally states "Kleene's theorem" as the coincidence of regular and rational languages.[9] Other authors simply define "rational expression" and "regular expressions" as synonymous and do the same with "rational languages" and "regular languages".[1][2]

Apparently, the term regular originates from a 1951 technical report where Kleene introduced regular events and explicitly welcomed "any suggestions as to a more descriptive term".[10] Noam Chomsky, in his 1959 seminal article, used the term regular in a different meaning at first (referring to what is called Chomsky normal form today),[11] but noticed that his finite state languages were equivalent to Kleene's regular events.[12]

Closure properties

[edit]The regular languages are closed under various operations, that is, if the languages K and L are regular, so is the result of the following operations:

- the set-theoretic Boolean operations: union K ∪ L, intersection K ∩ L, and complement L, hence also relative complement K − L.[13]

- the regular operations: K ∪ L, concatenation , and Kleene star L*.[14]

- the trio operations: string homomorphism, inverse string homomorphism, and intersection with regular languages. As a consequence they are closed under arbitrary finite state transductions, like quotient K / L with a regular language. Even more, regular languages are closed under quotients with arbitrary languages: If L is regular then L / K is regular for any K.[15]

- the reverse (or mirror image) LR.[16] Given a nondeterministic finite automaton to recognize L, an automaton for LR can be obtained by reversing all transitions and interchanging starting and finishing states. This may result in multiple starting states; ε-transitions can be used to join them.

Decidability properties

[edit]Given two deterministic finite automata A and B, it is decidable whether they accept the same language.[17] As a consequence, using the above closure properties, the following problems are also decidable for arbitrarily given deterministic finite automata A and B, with accepted languages LA and LB, respectively:

- Containment: is LA ⊆ LB ?[note 10]

- Disjointness: is LA ∩ LB = {} ?

- Emptiness: is LA = {} ?

- Universality: is LA = Σ* ?

- Membership: given a ∈ Σ*, is a ∈ LB ?

For regular expressions, the universality problem is NP-complete already for a singleton alphabet.[18] For larger alphabets, that problem is PSPACE-complete.[19] If regular expressions are extended to allow also a squaring operator, with "A2" denoting the same as "AA", still just regular languages can be described, but the universality problem has an exponential space lower bound,[20][21][22] and is in fact complete for exponential space with respect to polynomial-time reduction.[23]

For a fixed finite alphabet, the theory of the set of all languages – together with strings, membership of a string in a language, and for each character, a function to append the character to a string (and no other operations) – is decidable, and its minimal elementary substructure consists precisely of regular languages. For a binary alphabet, the theory is called S2S.[24]

Complexity results

[edit]In computational complexity theory, the complexity class of all regular languages is sometimes referred to as REGULAR or REG and equals DSPACE(O(1)), the decision problems that can be solved in constant space (the space used is independent of the input size). REGULAR ≠ AC0, since it (trivially) contains the parity problem of determining whether the number of 1 bits in the input is even or odd and this problem is not in AC0.[25] On the other hand, REGULAR does not contain AC0, because the nonregular language of palindromes, or the nonregular language can both be recognized in AC0.[26]

If a language is not regular, it requires a machine with at least Ω(log log n) space to recognize (where n is the input size).[27] In other words, DSPACE(o(log log n)) equals the class of regular languages.[27] In practice, most nonregular problems are studied in a setting with at least logarithmic space, as this is the amount of space required to store a pointer into the input tape.[28]

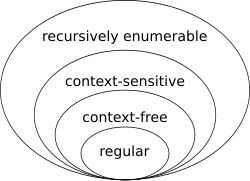

Location in the Chomsky hierarchy

[edit]

To locate the regular languages in the Chomsky hierarchy, one notices that every regular language is context-free. The converse is not true: for example, the language consisting of all strings having the same number of as as bs is context-free but not regular. To prove that a language is not regular, one often uses the Myhill–Nerode theorem and the pumping lemma. Other approaches include using the closure properties of regular languages[29] or quantifying Kolmogorov complexity.[30]

Important subclasses of regular languages include:

- Finite languages, those containing only a finite number of words.[31] These are regular languages, as one can create a regular expression that is the union of every word in the language.

- Star-free languages, those that can be described by a regular expression constructed from the empty symbol, letters, concatenation and all Boolean operators (see algebra of sets) including complementation but not the Kleene star: this class includes all finite languages.[32]

Number of words in a regular language

[edit]Let denote the number of words of length in . The ordinary generating function for L is the formal power series

The generating function of a language L is a rational function if L is regular.[33] Hence for every regular language the sequence is constant-recursive; that is, there exist an integer constant , complex constants and complex polynomials such that for every the number of words of length in is .[34][35][36][37]

Thus, non-regularity of certain languages can be proved by counting the words of a given length in . Consider, for example, the Dyck language of strings of balanced parentheses. The number of words of length in the Dyck language is equal to the Catalan number , which is not of the form , witnessing the non-regularity of the Dyck language. Care must be taken since some of the eigenvalues could have the same magnitude. For example, the number of words of length in the language of all even binary words is not of the form , but the number of words of even or odd length are of this form; the corresponding eigenvalues are . In general, for every regular language there exists a constant such that for all , the number of words of length is asymptotically .[38]

The zeta function of a language L is[33]

The zeta function of a regular language is not in general rational, but that of an arbitrary cyclic language is.[39][40]

Generalizations

[edit]The notion of a regular language has been generalized to infinite words (see ω-automata) and to trees (see tree automaton).

Rational set generalizes the notion (of regular/rational language) to monoids that are not necessarily free. Likewise, the notion of a recognizable language (by a finite automaton) has namesake as recognizable set over a monoid that is not necessarily free. Howard Straubing notes in relation to these facts that “The term "regular language" is a bit unfortunate. Papers influenced by Eilenberg's monograph[41] often use either the term "recognizable language", which refers to the behavior of automata, or "rational language", which refers to important analogies between regular expressions and rational power series. (In fact, Eilenberg defines rational and recognizable subsets of arbitrary monoids; the two notions do not, in general, coincide.) This terminology, while better motivated, never really caught on, and "regular language" is used almost universally.”[42]

Rational series is another generalization, this time in the context of a formal power series over a semiring. This approach gives rise to weighted rational expressions and weighted automata. In this algebraic context, the regular languages (corresponding to Boolean-weighted rational expressions) are usually called rational languages.[43][44] Also in this context, Kleene's theorem finds a generalization called the Kleene–Schützenberger theorem.

Learning from examples

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ 1. ⇒ 2. by Thompson's construction algorithm

- ^ 2. ⇒ 1. by Kleene's algorithm or using Arden's lemma

- ^ 2. ⇒ 3. by the powerset construction

- ^ 3. ⇒ 2. since the former definition is stronger than the latter

- ^ 2. ⇒ 4. see Hopcroft, Ullman (1979), Theorem 9.2, p.219

- ^ 4. ⇒ 2. see Hopcroft, Ullman (1979), Theorem 9.1, p.218

- ^ 3. ⇔ 10. by the Myhill–Nerode theorem

- ^ u ~ v is defined as: uw ∈ L if and only if vw ∈ L for all w ∈ Σ*

- ^ 3. ⇔ 11. see the proof in the Syntactic monoid article, and see p. 160 in Holcombe, W.M.L. (1982). Algebraic automata theory. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-60492-3. Zbl 0489.68046.

- ^ Check if LA ∩ LB = LA. Deciding this property is NP-hard in general; see File:RegSubsetNP.pdf for an illustration of the proof idea.

References

[edit]- Berstel, Jean; Reutenauer, Christophe (2011). Noncommutative rational series with applications. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications. Vol. 137. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19022-0. Zbl 1250.68007.

- Eilenberg, Samuel (1974). Automata, Languages, and Machines. Volume A. Pure and Applied Mathematics. Vol. 58. New York: Academic Press. Zbl 0317.94045.

- Salomaa, Arto (1981). Jewels of Formal Language Theory. Pitman Publishing. ISBN 0-273-08522-0. Zbl 0487.68064.

- Sipser, Michael (1997). Introduction to the Theory of Computation. PWS Publishing. ISBN 0-534-94728-X. Zbl 1169.68300. Chapter 1: Regular Languages, pp. 31–90. Subsection "Decidable Problems Concerning Regular Languages" of section 4.1: Decidable Languages, pp. 152–155.

- Philippe Flajolet and Robert Sedgewick, Analytic Combinatorics: Symbolic Combinatorics. Online book, 2002.

- John E. Hopcroft; Jeffrey D. Ullman (1979). Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02988-X.

- Alfred V. Aho and John E. Hopcroft and Jeffrey D. Ullman (1974). The Design and Analysis of Computer Algorithms. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 9780201000290.

- ^ a b Ruslan Mitkov (2003). The Oxford Handbook of Computational Linguistics. Oxford University Press. p. 754. ISBN 978-0-19-927634-9.

- ^ a b c Mark V. Lawson (2003). Finite Automata. CRC Press. pp. 98–103. ISBN 978-1-58488-255-8.

- ^ Sheng Yu (1997). "Regular languages". In Grzegorz Rozenberg; Arto Salomaa (eds.). Handbook of Formal Languages: Volume 1. Word, Language, Grammar. Springer. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-540-60420-4.

- ^ Eilenberg (1974), p. 16 (Example II, 2.8) and p. 25 (Example II, 5.2).

- ^ M. Weyer: Chapter 12 - Decidability of S1S and S2S, p. 219, Theorem 12.26. In: Erich Grädel, Wolfgang Thomas, Thomas Wilke (Eds.): Automata, Logics, and Infinite Games: A Guide to Current Research. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2500, Springer 2002.

- ^ Robert Sedgewick; Kevin Daniel Wayne (2011). Algorithms. Addison-Wesley Professional. p. 794. ISBN 978-0-321-57351-3.

- ^ Jean-Paul Allouche; Jeffrey Shallit (2003). Automatic Sequences: Theory, Applications, Generalizations. Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-521-82332-6.

- ^ Kenneth Rosen (2011). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications 7th edition. McGraw-Hill Science. pp. 873–880.

- ^ Horst Bunke; Alberto Sanfeliu (January 1990). Syntactic and Structural Pattern Recognition: Theory and Applications. World Scientific. p. 248. ISBN 978-9971-5-0566-0.

- ^ Stephen Cole Kleene (Dec 1951). Representation of Events in Nerve Nets and Finite Automata (PDF) (Research Memorandum). U.S. Air Force / RAND Corporation. Here: p.46

- ^ Noam Chomsky (1959). "On Certain Formal Properties of Grammars" (PDF). Information and Control. 2 (2): 137–167. doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(59)90362-6. Here: Definition 8, p.149

- ^ Chomsky 1959, Footnote 10, p.150

- ^ Salomaa (1981) p.28

- ^ Salomaa (1981) p.27

- ^ Fellows, Michael R.; Langston, Michael A. (1991). "Constructivity issues in graph algorithms". In Myers, J. Paul Jr.; O'Donnell, Michael J. (eds.). Constructivity in Computer Science, Summer Symposium, San Antonio, Texas, USA, June 19-22, Proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 613. Springer. pp. 150–158. doi:10.1007/BFB0021088. ISBN 978-3-540-55631-2.

- ^ Hopcroft, Ullman (1979), Chapter 3, Exercise 3.4g, p. 72

- ^ Hopcroft, Ullman (1979), Theorem 3.8, p.64; see also Theorem 3.10, p.67

- ^ Aho, Hopcroft, Ullman (1974), Exercise 10.14, p.401

- ^ Aho, Hopcroft, Ullman (1974), Theorem 10.14, p399

- ^ Hopcroft, Ullman (1979), Theorem 13.15, p.351

- ^ A.R. Meyer & L.J. Stockmeyer (Oct 1972). The Equivalence Problem for Regular Expressions with Squaring Requires Exponential Space (PDF). 13th Annual IEEE Symp. on Switching and Automata Theory. pp. 125–129.

- ^ L. J. Stockmeyer; A. R. Meyer (1973). "Word Problems Requiring Exponential Time". Proc. 5th ann. symp. on Theory of computing (STOC) (PDF). ACM. pp. 1–9.

- ^ Hopcroft, Ullman (1979), Corollary p.353

- ^ Weyer, Mark (2002). "Decidability of S1S and S2S". Automata, Logics, and Infinite Games. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2500. Springer. pp. 207–230. doi:10.1007/3-540-36387-4_12. ISBN 978-3-540-00388-5.

- ^ Furst, Merrick; Saxe, James B.; Sipser, Michael (1984). "Parity, circuits, and the polynomial-time hierarchy". Mathematical Systems Theory. 17 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1007/BF01744431. MR 0738749. S2CID 14677270.

- ^ Cook, Stephen; Nguyen, Phuong (2010). Logical foundations of proof complexity (1. publ. ed.). Ithaca, NY: Association for Symbolic Logic. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-521-51729-4.

- ^ a b J. Hartmanis, P. L. Lewis II, and R. E. Stearns. Hierarchies of memory-limited computations. Proceedings of the 6th Annual IEEE Symposium on Switching Circuit Theory and Logic Design, pp. 179–190. 1965.

- ^ Sipser (1997) p.349

- ^ "How to prove that a language is not regular?". cs.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Hromkovič, Juraj (2004). Theoretical computer science: Introduction to Automata, Computability, Complexity, Algorithmics, Randomization, Communication, and Cryptography. Springer. pp. 76–77. ISBN 3-540-14015-8. OCLC 53007120.

- ^ A finite language should not be confused with a (usually infinite) language generated by a finite automaton.

- ^ Volker Diekert; Paul Gastin (2008). "First-order definable languages" (PDF). In Jörg Flum; Erich Grädel; Thomas Wilke (eds.). Logic and automata: history and perspectives. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-576-6.

- ^ a b Honkala, Juha (1989). "A necessary condition for the rationality of the zeta function of a regular language". Theor. Comput. Sci. 66 (3): 341–347. doi:10.1016/0304-3975(89)90159-x. Zbl 0675.68034.

- ^ Flajolet & Sedgweick, section V.3.1, equation (13).

- ^ "Number of words in the regular language $(00)^*$". cs.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ "Proof of theorem for arbitrary DFAs".

- ^ "Number of words of a given length in a regular language". cs.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Flajolet & Sedgewick (2002) Theorem V.3

- ^ Berstel, Jean; Reutenauer, Christophe (1990). "Zeta functions of formal languages". Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 321 (2): 533–546. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.309.3005. doi:10.1090/s0002-9947-1990-0998123-x. Zbl 0797.68092.

- ^ Berstel & Reutenauer (2011) p.222

- ^ Samuel Eilenberg. Automata, languages, and machines. Academic Press. in two volumes "A" (1974, ISBN 9780080873749) and "B" (1976, ISBN 9780080873756), the latter with two chapters by Bret Tilson.

- ^ Straubing, Howard (1994). Finite automata, formal logic, and circuit complexity. Progress in Theoretical Computer Science. Basel: Birkhäuser. p. 8. ISBN 3-7643-3719-2. Zbl 0816.68086.

- ^ Berstel & Reutenauer (2011) p.47

- ^ Sakarovitch, Jacques (2009). Elements of automata theory. Translated from the French by Reuben Thomas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-521-84425-3. Zbl 1188.68177.

Further reading

[edit]- Kleene, S.C.: Representation of events in nerve nets and finite automata. In: Shannon, C.E., McCarthy, J. (eds.) Automata Studies, pp. 3–41. Princeton University Press, Princeton (1956); it is a slightly modified version of his 1951 RAND Corporation report of the same title, RM704.

- Sakarovitch, J (1987). "Kleene's theorem revisited". Trends, Techniques, and Problems in Theoretical Computer Science. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 1987. pp. 39–50. doi:10.1007/3540185356_29. ISBN 978-3-540-18535-2.

External links

[edit]Regular language

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Formal Definition

In formal language theory, an alphabet is a finite nonempty set of symbols, such as .[9] A string over is a finite sequence of symbols from , including the empty string , which has length zero and contains no symbols.[9] The set of all finite strings over , denoted , is known as the Kleene star of and forms the universal set for languages over .[9] A regular language over an alphabet is a subset consisting of all strings generated by a regular expression over , or equivalently, all strings accepted by a finite automaton over .[10] This definition captures the simplest class of formal languages in the Chomsky hierarchy.[11] The formal syntax of regular expressions over is defined inductively as follows:- The empty set is a regular expression denoting the empty language.

- Any symbol is a regular expression denoting the singleton set .

- The empty string is a regular expression denoting .

- If and are regular expressions denoting languages and , then:

- (or ) is a regular expression denoting (union).

- is a regular expression denoting (concatenation).

- is a regular expression denoting the Kleene star , where and for .

Parentheses are used to indicate precedence, with star having highest precedence, followed by concatenation, then union.[10]

Examples

Regular languages can be illustrated through simple sets of strings that can be recognized by finite automata, which maintain a finite amount of memory to track patterns. A classic example is the language ends with 1, consisting of all binary strings terminating in the symbol 1, such as 01, 101, and 111. This language is regular because a deterministic finite automaton (DFA) with two states suffices: a start state (non-accepting, representing the last symbol was 0 or start) and an accepting state (last symbol was 1), with transitions , , , and .[12] Another basic regular language is , the set of all even-length binary strings over , including the empty string (length 0), 00, 01, 10, 11 (length 2), and so on. Recognition requires tracking parity with a DFA featuring two states: (even length so far, accepting) as the start state and (odd length, non-accepting), with transitions swapping states on each input symbol regardless of 0 or 1.[13] Trivial cases include the empty language , which contains no strings and is recognized by a DFA with no accepting states, and the full language (for alphabet ), encompassing all possible binary strings, accepted by a single-state DFA where the sole state is accepting and loops on all inputs.[14] In contrast, the language , such as , 01, 0011, and 000111, is not regular because any purported DFA would require unbounded states to match the equal number of 0s and 1s, violating the finite memory constraint; this is shown via the pumping lemma for regular languages.[15] These examples can be described using regular expressions, such as for and for even-length strings.[16] In practice, regular languages underpin pattern matching in text processing, like validating email addresses with regex patterns that check formats such as local-part@domain (e.g., user@example.com), ensuring finite-state recognition of structural rules without infinite memory.[17]Equivalent Formalisms

Regular Expressions

Regular expressions provide a symbolic notation for specifying regular languages, originally introduced by Stephen Kleene in his 1956 work on representation of events in finite automata.[18] They consist of atomic expressions combined using operations that correspond to union, concatenation, and Kleene star on languages. The syntax of regular expressions over an alphabet is defined recursively as follows: the atomic expressions are the empty set , the empty string , and single symbols ; if and are regular expressions, then so are (union), (concatenation), and (Kleene star).[19] Parentheses are used for grouping, and precedence rules apply: Kleene star has highest precedence, followed by concatenation, then union, allowing omission of some parentheses (e.g., means ).[20] The semantics of a regular expression , denoted , map it to the language it represents, defined recursively: , , for ; (concatenation of languages); ; and , where and .[19] For example, the expression denotes the language of all strings consisting of zero or more 's followed by a single . Every regular expression can be converted to an equivalent nondeterministic finite automaton (NFA) using Thompson's construction, an algorithm that builds the NFA recursively from subexpressions. The process starts with basic NFAs for atoms and combines them for operations, ensuring each partial NFA has a unique start state and accept state :- For : States and with no transitions between them.

- For : States and connected by an -transition.

- For literal : States and connected by a transition labeled .

+ (one or more) and ? (zero or one), bounded repetition {m,n}, and character classes [abc] or [:digit:].[21] These go beyond theoretical regular expressions, as they can describe non-regular languages when combined (e.g., backreferences in some implementations), and rely on implementation-specific behaviors like greedy matching.[21]

Finite Automata

Finite automata serve as fundamental computational models for recognizing regular languages, processing input strings sequentially through a finite number of states based on transitions determined by the alphabet symbols. These machines operate without memory beyond their current state, making them suitable for pattern matching in linear time relative to the input length. The two primary variants are deterministic finite automata (DFAs), which have unique transitions for each input symbol from any state, and nondeterministic finite automata (NFAs), which allow multiple possible transitions or even spontaneous moves without consuming input.[22] A DFA is formally defined as a 5-tuple , where is a finite set of states, is a finite input alphabet, is the transition function that specifies a unique next state for each state-symbol pair, is the initial state, and is the set of accepting (or final) states.[22] To accept a string , the DFA begins in and applies successively for each symbol in ; the string is accepted if the resulting state is in , otherwise rejected.[22] This deterministic behavior ensures exactly one computation path per input, facilitating efficient simulation. An NFA extends the DFA model to a 5-tuple , where the transition function is , allowing a set of possible next states (including the empty set) for each state and input symbol or the empty string .[22] Acceptance occurs if there exists at least one computation path from to a state in that consumes the entire input string, accounting for -transitions that enable moves without reading symbols.[22] Despite nondeterminism, NFAs recognize exactly the same class of languages as DFAs, as any NFA can be converted to an equivalent DFA via the powerset construction, which treats subsets of as new states and simulates all possible NFA paths in parallel.[22] In this construction, the DFA's states are elements of , the initial state is , accepting states are those subsets intersecting , and transitions are defined by applying to all states in a subset and taking the union.[22] To optimize DFAs by reducing the number of states while preserving the recognized language, minimization algorithms partition states into equivalence classes based on distinguishability by future inputs. Hopcroft's algorithm achieves this in time by iteratively refining partitions using a breadth-first search-like refinement process on the state graph, improving upon earlier methods.[23] This complexity makes it practical for large automata in applications like compiler design and lexical analysis. As an illustrative example, consider an NFA recognizing binary strings over with an even number of 1's. The NFA has states , where (initial and accepting) tracks even parity and tracks odd parity, with transitions: , , , , and no -transitions. For input "101", the computation paths yield states (rejecting, odd 1's) or parallel simulations confirming acceptance only for even counts like "110" ending in . Applying powerset construction, the DFA states are , but is unreachable; transitions mirror the NFA since each yields a singleton, resulting in an identical two-state DFA with states renamed as even and odd parity. NFAs can also be constructed systematically from regular expressions using methods like Thompson's construction.[22]Regular Grammars

A regular grammar, also known as a type-3 grammar in the Chomsky hierarchy, is a formal grammar that generates precisely the regular languages through restrictions on its production rules to ensure linearity in one direction. These grammars are classified as either right-linear or left-linear. In a right-linear grammar, all productions are of the form or , where and are nonterminal symbols, is a terminal symbol from the alphabet , and there is a distinguished start symbol . Left-linear grammars mirror this structure with productions or . A grammar is regular if it is either right-linear or left-linear but not a mixture of both forms.[24] The language generated by a regular grammar consists of all finite strings of terminals that can be obtained from the start symbol via a derivation, which is a sequence of substitutions applying the production rules. In each derivation step, a nonterminal is replaced by the right-hand side of a matching production, proceeding until only terminals remain; for regular grammars, derivations are inherently linear due to the single nonterminal allowed on the right-hand side. This generative process enumerates the language's strings without ambiguity in structure, though multiple derivations may yield the same string in nondeterministic cases.[24] Regular grammars are equivalent to nondeterministic finite automata (NFAs), with constructive algorithms establishing bidirectional conversions. To convert a right-linear regular grammar to an NFA, map each nonterminal to a state, designate as the start state, add transitions for each production , introduce transitions to a new accepting state for each , and mark states accepting if there is a production . The reverse conversion from an NFA to a regular grammar assigns nonterminals to states, with the start state as , and generates productions from transitions and from transitions to accepting states. These algorithms preserve the language exactly, confirming the equivalence.[24][25] As an illustrative example, consider the regular language , which matches the regular expression . A corresponding right-linear grammar is , with productions , . A derivation for the string (i.e., "aabbb") proceeds as follows:. The derivation tree forms a right-skewed spine: the root branches to and another (twice for the 's), then to , which branches to and (thrice), terminating in . This tree visually captures the sequential generation, with leaves yielding the terminal string.[26]

Properties

Closure Properties

Regular languages possess notable closure properties under several fundamental operations on formal languages. These properties underscore the robustness of the class, as the result of applying such an operation to one or more regular languages is always regular. Proofs of closure typically rely on constructive methods using finite automata, leveraging the equivalence between regular languages and the languages accepted by nondeterministic finite automata (NFAs) or deterministic finite automata (DFAs).[27] The class of regular languages is closed under union. Given regular languages and accepted by NFAs and , construct an NFA with a new start state and -transitions from to and ; the transition function extends and . This accepts exactly , as paths from reach accepting states via either submachine.[27] Closure under intersection holds via the product automaton construction. For DFAs and as above, form the product DFA , where for states , , and symbol . A string is accepted by if and only if it is accepted by both and , so accepts . Since the state space is finite (), is a DFA.[28] Regular languages are closed under complementation. If is accepted by a DFA , then the complement is accepted by the DFA , which swaps accepting and non-accepting states. Every string drives to a state in precisely when reaches a state not in , ensuring acceptance of .[5] The class is closed under concatenation. For regular languages and accepted by NFAs and , construct by adding -transitions from each state in to , using states , start , and accept states . A string with , reaches an accepting state via the path for in followed by to for , and no other strings are accepted.[29] Closure under the Kleene star operation (with ) is established using NFAs. For accepted by NFA , create with new states (start) and (sole accept), -transitions from to and from to , and from each state in via to both and . This allows zero or more repetitions of paths accepting strings in .[29] Regular languages are closed under reversal, where and reverses . Given NFA for , construct NFA by reversing all transitions (if includes , add including ), setting start states to (with -transitions if multiple to a new start if needed, but typically direct), and accept state to . A path labeled from to some in corresponds to a path labeled from to in , hence from start to accept in .[30] The class is closed under homomorphism. A homomorphism maps each symbol to a string in . If is regular, accepted by DFA , then is accepted by NFA , where for each transition in , add a chain of states and transitions spelling from to (introducing intermediate states as needed for the fixed-length ); -transitions connect chains. Since is fixed per and finite, the added states are finite, and processing simulates on while outputting , accepting if .[31] Closure under inverse homomorphism holds: For homomorphism and regular accepted by DFA , the inverse is accepted by NFA , where states include copies of for each position in the images ; on input , from state , chain through applied to the symbols of using intermediate states, ending at . The finite added states per (bounded by ) ensure finiteness; is accepted if the simulation reaches after . Regular languages are closed under the (right) quotient operation when the divisor is regular: if are regular, then is regular. The construction modifies the DFA for by redefining accepting states to those from which some string in reaches an original accepting state, using the finite state space.[32] However, the class is not closed under quotient when the dividend is non-regular. For a counterexample, let (non-regular) and (regular); then , which is non-regular.[32] The following table summarizes the closure operations and corresponding automaton constructions:| Operation | Construction Method |

|---|---|

| Union | New NFA start state with -transitions to starts of input NFAs; union of accept sets |

| Intersection | Product DFA with synchronized transitions on symbols; product of start and accept sets |

| Complement | Same DFA, but swap accepting and non-accepting states |

| Concatenation | NFA combining input NFAs with -transitions from accept of first to start of second |

| Kleene star | Augmented NFA with new start/accept state and -loops from accepts to start |

| Reversal | Reverse transitions in NFA; original accepts become starts (via if needed), original start becomes accept |

| Homomorphism | NFA with -chains replacing transitions for strings |

| Inverse homomorphism | NFA simulating transitions on full strings via chained states per symbol |

Decidability Properties

Regular languages enjoy strong decidability properties, allowing algorithms to resolve key questions about them efficiently. Unlike higher classes in the Chomsky hierarchy, all standard decision problems for regular languages—when presented via finite automata, regular expressions, or regular grammars—are computable in polynomial time relative to the input size. The membership problem, determining whether a given string belongs to a regular language described by a deterministic finite automaton (DFA) , is decidable by simulating on starting from . If the final state is in , then . This simulation requires examining one transition per symbol in , yielding a time complexity of .[33] Emptiness, checking if for a DFA , is decidable via graph reachability: model the DFA as a directed graph with states as nodes and transitions as edges, then use breadth-first search (BFS) from to detect if any state in is reachable. Since the graph has nodes and at most edges, BFS runs in time. For nondeterministic finite automata (NFAs), first convert to a DFA using subset construction, which is exponential but finite.[34] Finiteness, determining if , is decidable by analyzing the DFA's structure for cycles that contribute to infinite languages. Specifically, compute the reachable states from , then check for cycles within the subgraph of states from which an accepting state is reachable; the language is infinite if and only if such a cycle exists. This involves graph traversal algorithms like depth-first search for cycle detection, again in time.[35] Equivalence between two regular languages given by DFAs and is decidable by minimizing both automata and verifying isomorphism of the results, or by constructing DFAs for (symmetric difference) and testing emptiness. Minimization partitions states into equivalence classes using a table-filling or partition refinement algorithm, with Hopcroft's algorithm achieving time, where is the total number of states across both DFAs.[36] The Myhill-Nerode theorem underpins these results by characterizing regular languages via the right-congruence relation if iff for all ; is regular if and only if the number of equivalence classes (the index) is finite, equaling the size of the minimal DFA. This equivalence relation directly informs DFA minimization and equivalence testing by identifying indistinguishable states.[37] In contrast to regular languages, non-regular classes like context-sensitive languages exhibit undecidability for problems such as equivalence; for instance, while membership in is decidable, deciding equivalence among context-sensitive languages in general is not.[34]Complexity Results

The conversion from a nondeterministic finite automaton (NFA) with states to an equivalent deterministic finite automaton (DFA) via the subset construction algorithm can result in an exponential blowup in the number of states, reaching up to in the worst case.[38] This worst-case bound is tight, as there exist NFAs requiring a DFA with exactly states for equivalence.[39] Minimization of a DFA with states and alphabet size can be performed in time using Hopcroft's algorithm, which refines an initial partition of states based on distinguishability. This bound is asymptotically optimal, as the algorithm's partitioning process necessitates handling logarithmic factors in the worst case.[40] The construction of an NFA from a regular expression of length using Thompson's method proceeds in linear time, , by inductively building sub-NFAs for basic symbols and combining them via epsilon transitions for union, concatenation, and Kleene star operations. This efficiency stems from the epsilon-move rules, which add a constant number of states and transitions per operator without requiring determinization.[41] The emptiness problem for DFAs—determining whether the language is empty—is solvable in linear time, , by checking reachability from the initial state to any accepting state via graph traversal.[42] Equivalence of two DFAs with and states can be decided in polynomial time, specifically , by constructing the product automaton and testing emptiness of the symmetric difference.[43] For NFAs, emptiness is NL-complete, reducible to graph reachability, while universality (whether the language equals ) is PSPACE-complete.[44] State complexity measures the minimal number of states required in a DFA recognizing the result of an operation on input DFAs. For union of languages recognized by an -state DFA and an -state DFA, up to states may be necessary and sufficient in the worst case, achieved via the product construction with merged initial and accepting states.[39] Lower bounds demonstrate that this bound is tight for certain languages over binary alphabets.[45] Similarly, intersection requires up to states, using the standard product automaton. Reversal of an -state DFA language has state complexity up to , as the reverse may require determinization of an equivalent NFA; tight examples exist over suitable alphabets.[38] The following table summarizes the time and state complexities for key operations on regular languages represented by DFAs or NFAs:| Operation | Time Complexity | State Complexity (Worst Case) |

|---|---|---|

| NFA to DFA (subset construction) | $ O(2^{ | Q |

| DFA Minimization (Hopcroft) | $ O(n \log n \cdot | \Sigma |

| RegExp to NFA (Thompson) | states | |

| DFA Emptiness | N/A | |

| DFA Equivalence | $ O(mn \cdot | \Sigma |

| NFA Emptiness | NL-complete | N/A |

| Union (DFAs, , states) | $ O(mn \cdot | \Sigma |

| Intersection (DFAs) | $ O(mn \cdot | \Sigma |

| Reversal (DFA to minimal DFA) | $ O(2^n \cdot | \Sigma |