Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Automaton

View on Wikipedia

An automaton (/ɔːˈtɒmətən/ ⓘ; pl.: automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions.[1] Some automata, such as bellstrikers in mechanical clocks, are designed to give the illusion to the casual observer that they are operating under their own power or will, like a mechanical robot. The term has long been commonly associated with automated puppets that resemble moving humans or animals, built to impress and/or to entertain people.

Animatronics are a modern type of automata with electronics, often used for the portrayal of characters or creatures in films and in theme park attractions.

Etymology

[edit]The word automaton is the latinization of the Ancient Greek automaton (αὐτόματον), which means "acting of one's own will". It was first used by Homer to describe an automatic door opening,[2] or automatic movement of wheeled tripods.[3] It is more often used to describe non-electronic moving machines, especially those that have been made to resemble human or animal actions, such as the jacks on old public striking clocks, or the cuckoo and any other animated figures on a cuckoo clock.

History

[edit]Ancient

[edit]

There are many examples of automata in Greek mythology: Hephaestus created automata for his workshop;[4][5] Talos was an artificial man of bronze; King Alkinous of the Phaiakians employed gold and silver watchdogs.[6][7] According to Aristotle, Daedalus used quicksilver to make his wooden statue of Aphrodite move.[8][9] In other Greek legends he used quicksilver to install voice in his moving statues.

The automata in the Hellenistic world were intended as tools, toys, religious spectacles, or prototypes for demonstrating basic scientific principles. Numerous water-powered automata were built by Ktesibios, a Greek inventor and the first head of the Great Library of Alexandria; for example, he "used water to sound a whistle and make a model owl move. He had invented the world's first 'cuckoo clock'".[a] This tradition continued in Alexandria with inventors such as the Greek mathematician Hero of Alexandria (sometimes known as Heron), whose writings on hydraulics, pneumatics, and mechanics described siphons, a fire engine, a water organ, the aeolipile, and a programmable cart.[10][11] Philo of Byzantium was famous for his inventions.

Complex mechanical devices are known to have existed in Hellenistic Greece, though the only surviving example is the Antikythera mechanism, the earliest known analog computer.[12] The clockwork is thought to have come originally from Rhodes, where there was apparently a tradition of mechanical engineering; the island was renowned for its automata; to quote Pindar's seventh Olympic Ode:

- The animated figures stand

- Adorning every public street

- And seem to breathe in stone, or

- move their marble feet.

However, the information gleaned from recent scans of the fragments indicate that it may have come from the colonies of Corinth in Sicily and implies a connection with Archimedes.

According to Jewish legend, King Solomon used his wisdom to design a throne with mechanical animals which hailed him as king when he ascended it; upon sitting down an eagle would place a crown upon his head, and a dove would bring him a Torah scroll. It is also said that when King Solomon stepped upon the throne, a mechanism was set in motion. As soon as he stepped upon the first step, a golden ox and a golden lion each stretched out one foot to support him and help him rise to the next step. On each side, the animals helped the King up until he was comfortably seated upon the throne.[13]

In ancient China, a curious account of automata is found in the Lie Zi text, believed to have originated around 400 BCE and compiled around the fourth century CE. Within it there is a description of a much earlier encounter between King Mu of Zhou (1023–957 BCE) and a mechanical engineer known as Yan Shi, an 'artificer'. The latter proudly presented the king with a very realistic and detailed life-size, human-shaped figure of his mechanical handiwork:

The king stared at the figure in astonishment. It walked with rapid strides, moving its head up and down, so that anyone would have taken it for a live human being. The artificer touched its chin, and it began singing, perfectly in tune. He touched its hand, and it began posturing, keeping perfect time...As the performance was drawing to an end, the robot winked its eye and made advances to the ladies in attendance, whereupon the king became incensed and would have had Yen Shih [Yan Shi] executed on the spot had not the latter, in mortal fear, instantly taken the robot to pieces to let him see what it really was. And, indeed, it turned out to be only a construction of leather, wood, glue and lacquer, variously coloured white, black, red and blue. Examining it closely, the king found all the internal organs complete—liver, gall, heart, lungs, spleen, kidneys, stomach and intestines; and over these again, muscles, bones and limbs with their joints, skin, teeth and hair, all of them artificial...The king tried the effect of taking away the heart, and found that the mouth could no longer speak; he took away the liver and the eyes could no longer see; he took away the kidneys and the legs lost their power of locomotion. The king was delighted.[14]

Other notable examples of automata include Archytas' dove, mentioned by Aulus Gellius.[15] Similar Chinese accounts of flying automata are written of the 5th century BC Mohist philosopher Mozi and his contemporary Lu Ban, who made artificial wooden birds (ma yuan) that could successfully fly according to the Han Fei Zi and other texts.[16]

Medieval

[edit]The manufacturing tradition of automata continued in the Greek world well into the Middle Ages. On his visit to Constantinople in 949 ambassador Liutprand of Cremona described automata in the emperor Theophilos' palace, including

"lions, made either of bronze or wood covered with gold, which struck the ground with their tails and roared with open mouth and quivering tongue," "a tree of gilded bronze, its branches filled with birds, likewise made of bronze gilded over, and these emitted cries appropriate to their species" and "the emperor's throne" itself, which "was made in such a cunning manner that at one moment it was down on the ground, while at another it rose higher and was to be seen up in the air."[17]

Similar automata in the throne room (singing birds, roaring and moving lions) were described by Luitprand's contemporary the Byzantine emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, in his book De Ceremoniis (Perì tês Basileíou Tákseōs).

In the mid-8th century, the first wind powered automata were built: "statues that turned with the wind over the domes of the four gates and the palace complex of the Round City of Baghdad". The "public spectacle of wind-powered statues had its private counterpart in the 'Abbasid palaces where automata of various types were predominantly displayed."[18] Also in the 8th century, the Muslim alchemist, Jābir ibn Hayyān (Geber), included recipes for constructing artificial snakes, scorpions, and humans that would be subject to their creator's control in his coded Book of Stones. In 827, Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun had a silver and golden tree in his palace in Baghdad, which had the features of an automatic machine. There were metal birds that sang automatically on the swinging branches of this tree built by Muslim inventors and engineers.[19][page needed] The Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir also had a silver and golden tree in his palace in Baghdad in 917, with birds on it flapping their wings and singing.[20] In the 9th century, the Banū Mūsā brothers invented a programmable automatic flute player and which they described in their Book of Ingenious Devices.[21]

Al-Jazari described complex programmable humanoid automata amongst other machines he designed and constructed in the Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices in 1206.[22] His automaton was a boat with four automatic musicians that floated on a lake to entertain guests at royal drinking parties.[23] His mechanism had a programmable drum machine with pegs (cams) that bump into little levers that operate the percussion. The drummer could be made to play different rhythms and drum patterns if the pegs were moved around.[24]

Al-Jazari constructed a hand washing automaton first employing the flush mechanism now used in modern toilets. It features a female automaton standing by a basin filled with water. When the user pulls the lever, the water drains and the automaton refills the basin.[25] His "peacock fountain" was another more sophisticated hand washing device featuring humanoid automata as servants who offer soap and towels. Mark E. Rosheim describes it as follows: "Pulling a plug on the peacock's tail releases water out of the beak; as the dirty water from the basin fills the hollow base a float rises and actuates a linkage which makes a servant figure appear from behind a door under the peacock and offer soap. When more water is used, a second float at a higher level trips and causes the appearance of a second servant figure—with a towel!"[26]

Al-Jazari thus appears to have been the first inventor to display an interest in creating human-like machines for practical purposes such as manipulating the environment for human comfort.[27] Lamia Balafrej has also pointed out the prevalence of the figure of the automated slave in al-Jazari's treatise.[28] Automated slaves were a frequent motif in ancient and medieval literature but it was not so common to find them described in a technical book. Balafrej has also written about automated female slaves, which appeared in timekeepers and as liquid-serving devices in medieval Arabic sources, thus suggesting a link between feminized forms of labor like housekeeping, medieval slavery, and the imaginary of automation.[29]

In 1066, the Chinese inventor Su Song built a water clock in the form of a tower which featured mechanical figurines which chimed the hours.[30]

Samarangana Sutradhara, a Sanskrit treatise by Bhoja (11th century), includes a chapter about the construction of mechanical contrivances (automata), including mechanical bees and birds, fountains shaped like humans and animals, and male and female dolls that refilled oil lamps, danced, played instruments, and re-enacted scenes from Hindu mythology.[31][32][33] [better source needed]

Villard de Honnecourt, in his 1230s sketchbook, depicted an early escapement mechanism in a drawing titled How to make an angel keep pointing his finger toward the Sun with an angel that would perpetually turn to face the sun. He also drew an automaton of a bird with jointed wings, which led to their design implementation in clocks.[34][35]

At the end of the thirteenth century, Robert II, Count of Artois, built a pleasure garden at his castle at Hesdin that incorporated several automata as entertainment in the walled park. The work was conducted by local workmen and overseen by the Italian knight Renaud Coignet. It included monkey marionettes, a sundial supported by lions and "wild men", mechanized birds, mechanized fountains and a bellows-operated organ. The park was famed for its automata well into the fifteenth century before it was destroyed by English soldiers in the sixteenth century.[36][37][38]

The Chinese author Xiao Xun wrote that when the Ming dynasty founder Hongwu (r. 1368–1398) was destroying the palaces of Khanbaliq belonging to the previous Yuan dynasty, there were—among many other mechanical devices—automata found that were in the shape of tigers.[39]

Renaissance and early modern

[edit]

The Renaissance witnessed a considerable revival of interest in automata. Hero's treatises were edited and translated into Latin and Italian. Hydraulic and pneumatic automata, similar to those described by Hero, were created for garden grottoes.

Giovanni Fontana, a Paduan engineer in 1420, developed Bellicorum instrumentorum liber[b] which includes a puppet of a camelid driven by a clothed primate twice the height of a human being and an automaton of Mary Magdalene.[41] He also created mechanical devils and rocket-propelled animal automata.[42][43]

While functional, early clocks were also often designed as novelties and spectacles which integrated features of automata. Many big and complex clocks with automated figures were built as public spectacles in European town centres. One of the earliest of these large clocks was the Strasbourg astronomical clock, built in the 14th century which takes up the entire side of a cathedral wall. It contained an astronomical calendar, automata depicting animals, saints and the life of Christ. The mechanical rooster of Strasbourg clock was active from 1352 to 1789.[44][45] The clock still functions to this day, but has undergone several restorations since its initial construction. The Prague astronomical clock was built in 1410, animated figures were added from the 17th century onwards.[46] Numerous clockwork automata were manufactured in the 16th century, principally by the goldsmiths of the Free Imperial Cities of central Europe. These wondrous devices found a home in the cabinet of curiosities or Wunderkammern of the princely courts of Europe.

In 1454, Duke Philip created an entertainment show named The extravagant Feast of the Pheasant, which was intended to influence the Duke's peers to participate in a crusade against the Ottomans but ended up being a grand display of automata, giants, and dwarves.[47]

A banquet in Camilla of Aragon's honor in Italy, 1475, featured a lifelike automated camel.[48] The spectacle was a part of a larger parade which continued over days.

Leonardo da Vinci sketched a complex mechanical knight, which he may have built and exhibited at a celebration hosted by Ludovico Sforza at the court of Milan around 1495. The design of Leonardo's robot was not rediscovered until the 1950s. A functional replica was later built that could move its arms, twist its head, and sit up.[49]

Da Vinci is frequently credited with constructing a mechanical lion, which he presented to King Francois I in Lyon in 1515. Although no record of the device's original designs remain, a recreation of this piece is housed at the Château du Clos Lucé.[50]

The Smithsonian Institution has in its collection a clockwork monk, about 15 in (380 mm) high, possibly dating as early as 1560. The monk is driven by a key-wound spring and walks the path of a square, striking his chest with his right arm, while raising and lowering a small wooden cross and rosary in his left hand, turning and nodding his head, rolling his eyes, and mouthing silent obsequies. From time to time, he brings the cross to his lips and kisses it. It is believed that the monk was manufactured by Juanelo Turriano, mechanician to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.[51]

The first description of a modern cuckoo clock was by the Augsburg nobleman Philipp Hainhofer in 1629.[52] The clock belonged to Prince Elector August von Sachsen. By 1650, the workings of mechanical cuckoos were understood and were widely disseminated in Athanasius Kircher's handbook on music, Musurgia Universalis. In what is the first documented description of how a mechanical cuckoo works, a mechanical organ with several automated figures is described.[53] In 18th-century Germany, clockmakers began making cuckoo clocks for sale.[46] Clock shops selling cuckoo clocks became commonplace in the Black Forest region by the middle of the 18th century.[54]

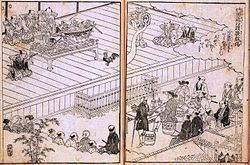

Japan adopted clockwork automata in the early 17th century as "karakuri" puppets. In 1662, Takeda Omi completed his first butai karakuri and then built several of these large puppets for theatrical exhibitions. Karakuri puppets went through a golden age during the Edo period (1603–1867).[55]

A new attitude towards automata is to be found in René Descartes when he suggested that the bodies of animals are nothing more than complex machines – the bones, muscles and organs could be replaced with cogs, pistons, and cams. Thus mechanism became the standard to which Nature and the organism was compared.[56] France in the 17th century was the birthplace of those ingenious mechanical toys that were to become prototypes for the engines of the Industrial Revolution. Thus, in 1649, when Louis XIV was still a child, François-Joseph de Camus designed for him a miniature coach, complete with horses and footmen, a page, and a lady within the coach; all these figures exhibited a perfect movement. According to Labat, General de Gennes constructed, in 1688, in addition to machines for gunnery and navigation, a peacock that walked and ate. Athanasius Kircher produced many automata to create Jesuit shows, including a statue which spoke and listened via a speaking tube.

The world's first successfully-built biomechanical automaton is considered to be The Flute Player, which could play twelve songs, created by the French engineer Jacques de Vaucanson in 1737. He also constructed The Tambourine Player and the Digesting Duck, a mechanical duck that – apart from quacking and flapping its wings – gave the false illusion of eating and defecating, seeming to endorse Cartesian ideas that animals are no more than machines of flesh.[57]

In 1769, a chess-playing machine called the Turk, created by Wolfgang von Kempelen, made the rounds of the courts of Europe purporting to be an automaton.[58]: 34 The Turk beat Benjamin Franklin in a game of chess when Franklin was ambassador to France.[58]: 34–35 The Turk was actually operated from inside by a hidden human director, and was not a true automaton.

Other 18th century automaton makers include the prolific Swiss Pierre Jaquet-Droz (see Jaquet-Droz automata) and his son Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz, and his contemporary Henri Maillardet. Maillardet, a Swiss mechanic, created an automaton capable of drawing four pictures and writing three poems. Maillardet's Automaton is now part of the collections at the Franklin Institute Science Museum in Philadelphia. Belgian-born John Joseph Merlin created the mechanism of the Silver Swan automaton, now at Bowes Museum.[59] A musical elephant made by the French clockmaker Hubert Martinet in 1774 is one of the highlights of Waddesdon Manor.[60] Tipu's Tiger is another late-18th century example of automata, made for Tipu Sultan, featuring a European soldier being mauled by a tiger. Catherine the Great of Russia was gifted a very large and elaborate Peacock Clock created by James Cox in 1781 now on display in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

According to philosopher Michel Foucault, Frederick the Great, king of Prussia from 1740 to 1786, was "obsessed" with automata.[61] According to Manuel de Landa, "he put together his armies as a well-oiled clockwork mechanism whose components were robot-like warriors".

In 1801, Joseph Jacquard built his loom automaton that was controlled autonomously with punched cards.

Automata, particularly watches and clocks, were popular in China during the 18th and 19th centuries, and items were produced for the Chinese market. Strong interest by Chinese collectors in the 21st century brought many interesting items to market where they have had dramatic realizations.[62]

Modern

[edit]The famous magician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805–1871) was known for creating automata for his stage shows.[63][58]: 33 Automata that acted according to a set of preset instructions were popular with magicians during this time.[58]: 33

In 1840, Italian inventor Innocenzo Manzetti constructed a flute-playing automaton, in the shape of a man, life-size, seated on a chair. Hidden inside the chair were levers, connecting rods and compressed air tubes, which made the automaton's lips and fingers move on the flute according to a program recorded on a cylinder similar to those used in player pianos. The automaton was powered by clockwork and could perform 12 different arias. As part of the performance, it would rise from the chair, bow its head, and roll its eyes.

The period between 1860 and 1910 is known as "The Golden Age of Automata". Mechanical coin-operated fortune tellers were introduced to boardwalks in Britain and America.[64] In Paris during this period, many small family based companies of automata makers thrived. From their workshops they exported thousands of clockwork automata and mechanical singing birds around the world. Although now rare and expensive, these French automata attract collectors worldwide. The main French makers were Bontems, Lambert, Phalibois, Renou, Roullet & Decamps, Theroude and Vichy.

Abstract automata theory started in mid-20th century with finite automata;[65] it is applied in branches of formal and natural science including computer science, physics, biology, as well as linguistics.

Contemporary automata continue this tradition with an emphasis on art, rather than technological sophistication. Contemporary automata are represented by the works of Cabaret Mechanical Theatre in the United Kingdom, Thomas Kuntz,[66] Arthur Ganson, Joe Jones and Le Défenseur du Temps by French artist Jacques Monestier.

Since 1990 Dutch artist Theo Jansen has been building large automated PVC structures called strandbeest (beach animal) that can walk on wind power or compressed air. Jansen claims that he intends them to automatically evolve and develop artificial intelligence, with herds roaming freely over the beach.

British sculptor Sam Smith (1908–1983) was a well-known maker of automata.[67][68][69]

Proposals

[edit]In 2016, the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts program studied a rover, the Automaton Rover for Extreme Environments, designed to survive for an extended time in Venus' environmental conditions. Unlike other modern automata, AREE is an automaton instead of a robot for practical reasons—Venus's harsh conditions, particularly its surface temperature of 462 °C (864 °F), make operating electronics there for any significant time impossible. It would be controlled by a mechanical computer and driven by wind power.[70]

Clocks

[edit]Automaton clocks are clocks which feature automatons within or around the housing and typically activate around the beginning of each hour, at each half hour, or at each quarter hour. They were largely produced from the 1st century BC to the end of the Victorian times in Europe. Older clocks typically featured religious characters or other mythical characters such as Death or Father Time. As time progressed, however, automaton clocks began to feature influential characters at the time of creation, such as kings, famous composers, or industrialists. Examples of automaton clocks include chariot clocks and cuckoo clocks. The Cuckooland Museum exhibits autonomous clocks. While automaton clocks are largely perceived to have been in use during medieval times in Europe, they are largely produced in Japan today.

In Automata theory, clocks are regarded as timed automatons, a type of finite automaton. Automaton clocks being finite essentially means that automaton clocks have a certain number of states in which they can exist.[71] The exact number is the number of combinations possible on a clock with the hour, minute, and second hand: 43,200. The title of timed automaton declares that the automaton changes states at a set rate, which for clocks is 1 state change every second. Clock automata only takes as input the time displayed by the previous state. The automata uses this input to produce the next state, a display of time 1 second later than the previous. Clock automata often also use the previous state's input to 'decide' whether or not the next state requires merely changing the hands on the clock, or if a special function is required, such as a mechanical bird popping out of a house like in cuckoo clocks.[72] This choice is evaluated through the position of complex gears, cams, axles, and other mechanical devices within the automaton.[73]

See also

[edit]- Automata theory, the study of abstract machines and automata

- Mechanical toy

- Wind-up toy

- Android

- Brazen head

- Cellular automaton

- Centre International de la Mécanique d'Art

- Christian Ristow

- Ctesibius

- Genesis Redux

- Fortune teller machine

- Giles Walker

- Golem

- Hero of Alexandria

- La Maison de la Magie Robert-Houdin display of 19th century automata

- Maillardet's automaton

- Marvin's Marvelous Mechanical Museum

- Orchestrion

- Singing bird box

- Theo Jansen

- Whirligig

Notes

[edit]- ^ This "first cuckoo clock" was further stated and described in the 2007 book The Rise and Fall of Alexandria: Birthplace of the Modern World by Justin Pollard and Howard Reid on page 132: "Soon Ctesibius's clocks were smothered in stopcocks and valves, controlling a host of devices from bells to puppets to mechanical doves that sang to mark the passing of each hour – the very first cuckoo clock!"

- ^ Full title: Bellicorum instrumentorum liber, cum figuris et fictitys litoris conscriptus, Latin for "Illustrated and encrypted book of war instruments"[40]

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of AUTOMATON". www.merriam-webster.com. 2024-01-04. Retrieved 2024-01-25.

- ^ Homer, Iliad, 5.749

- ^ Homer, Iliad, 18.376

- ^ Him she found sweating with toil as he moved to and fro about his bellows in eager haste; for he was fashioning tripods, twenty in all, to stand around the wall of his well-builded hall, and golden wheels had he set beneath the base of each that of themselves they might enter the gathering of the gods at his wish and again return to his house, a wonder to behold. Homer, Iliad 18.371–376 Archived 2023-01-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ he ... went forth halting; but there moved swiftly to support their lord handmaidens wrought of gold in the semblance of living maids. In them is understanding in their hearts, and in them speech and strength, and they know cunning handiwork by gift of the immortal gods. These busily moved to support their lord ... Homer, Iliad 18.417–421 Archived 2023-01-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The automatones of Greek Mythology online Archived 2013-11-06 at the Wayback Machine at the Theoi Project.

- ^ Hyginus. Astronomica 2.1

- ^ Aristotle (1907). "Chapter 3". De Anima. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, Daedalus". Archived from the original on 2022-11-08. Retrieved 2022-11-08.

- ^ Noel Sharkey (July 4, 2007), The programmable robot from Ancient Greece, vol. 2611, New Scientist

- ^ Brett, Gerard (July 1954), "The Automata in the Byzantine "Throne of Solomon"", Speculum, 29 (3): 477–487, doi:10.2307/2846790, ISSN 0038-7134, JSTOR 2846790, S2CID 163031682.

- ^ Harry Henderson (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Technology. Infobase Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4381-1003-5. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

The earliest known analog computing device is the Antikythera mechanism.

- ^ Mindel, Nissan. "King Solomon's Throne". www.chabad.org.

- ^ Needham, Volume 2, 53.

- ^ Noct. Att. L. 10

- ^ Needham, Volume 2, 54.

- ^ Safran, Linda (1998). Heaven on Earth: Art and the Church in Byzantium. Pittsburgh: Penn State Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-271-01670-1. Records Liutprand's description.

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (2005), Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, vol. 2, Routledge, p. 711, ISBN 0-415-96690-6

- ^ Ismail b. Ali Ebu'l Feda history, Weltgeschichte, hrsg. von Fleischer and Reiske 1789–94, 1831.

- ^ Le Strange, Guy (1922). Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate: from contemporary Arabic and Persian sources (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 256.

- ^ Koetsier, Teun (2001). "On the prehistory of programmable machines: musical automata, looms, calculators". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 36 (5). Elsevier: 589–603. doi:10.1016/S0094-114X(01)00005-2.

- ^ Balafrej, Lamia (2022). "Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206". 21: Inquiries into Art, History, and the Visual. 3 (4): 737–774. doi:10.11588/xxi.2022.4.91685. ISSN 2701-1569.Nadarajan, Gunalan (November 2008). "Islamic Automation: Al-Jazari's Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices".

- ^ al-Jazari (1026), "Category II, Chapter 4", Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, p. 107

- ^ "A 13th Century Programmable Robot". shef.ac.uk. University of Sheffield. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007.

- ^ Rosheim, Mark E. (1994), Robot Evolution: The Development of Anthrobotics, Wiley-IEEE, pp. 9–10, ISBN 0-471-02622-0 also at Internet Archive

- ^ Rosheim, Mark E. (1994), Robot Evolution: The Development of Anthrobotics, Wiley-IEEE, p. 9, ISBN 0-471-02622-0 also at Internet Archive

- ^ Rosheim, Mark E. (1994), Robot Evolution: The Development of Anthrobotics, Wiley-IEEE, p. 36, ISBN 0-471-02622-0

- ^ Balafrej, Lamia (2022). "Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206". 21: Inquiries into Art, History, and the Visual. 3 (4): 737–774. doi:10.11588/xxi.2022.4.91685. ISSN 2701-1569.

- ^ Balafrej, Lamia (2023). "Instrumental Jawārī: On Gender, Slavery, and Technology in Medieval Arabic Sources". Al-ʿUṣūr al-Wusṭā. 31: 96–126. doi:10.52214/uw.v31i.10486. ISSN 1068-1051.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 111.

- ^ Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (1987). History of Indian Theatre, Volume 1. Abhinav Publications. p. 68. ISBN 9788170172215.

- ^ Wujastyk, Dominik (2003). The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings. Penguin. p. 222. ISBN 9780140448245.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1965). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 9780521058032.

- ^ Bedini, Silvio A. (1964). "The Role of Automata in the History of Technology". Technology and Culture. 5 (1): 24–42. doi:10.2307/3101120. ISSN 0040-165X. JSTOR 3101120. S2CID 112528180.

- ^ de Solla Price, Derek J. (1964). "Automata and the Origins of Mechanism and Mechanistic Philosophy". Technology and Culture. 5 (1): 9–23. doi:10.2307/3101119. ISSN 0040-165X. JSTOR 3101119.

- ^ Truitt, Elly R. (2010). "The Garden of Earthly Delights: Mahaut of Artois and the Automata at Hesdin". Medieval Feminist Forum. 46: 74–79. doi:10.17077/1536-8742.1850.

- ^ Landsberg, Sylvia (1995). The Medieval Garden. New York: Thames and Hudson. p. 22.

- ^ Macdougall, Elisabeth B (1986). Medieval Gardens. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 9780884021469. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 133 & 508.

- ^ "Bellicorum Instrumentorum Liber | The Faith of a Heretic". www.krauselabs.net. 5 November 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Riskin, Jessica, ed. (2007). Genesis Redux: Essays in the History and Philosophy of Artificial Life ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Chicago [u.a.]: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226720807.

- ^ Grafton, Anthony (2007), "The Devil as Automaton", Genesis Redux, University of Chicago Press, pp. 46–62, doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226720838.003.0003, ISBN 978-0-226-72081-4, retrieved 2024-02-18

- ^ Battisti, Eugenio; Saccaro Del Buffa Battisti, Giuseppa; Fontana, Giovanni (1984). Le macchine cifrate di Giovanni Fontana: con la riproduzione del Cod. icon. 242 della Bayerische Staatsbibliothek di Monaco di Baviera e la decrittazione di esso e del Cod. lat. nouv. acq. 635 della Bibliothèque nationale di Parigi. Milano: Arcadia Edizioni. ISBN 978-88-85684-06-5.

- ^ Ungerer (1921). "L'Horloge Astronomique de la Cathedrale de Strasbourg". L'Astronomie. 35: 89–102. Bibcode:1921LAstr..35...89U.

- ^ Ungerer, Alfred; La Redaction (1921). "1921LAstr..35...89U Page 91". L'Astronomie. 35: 89. Bibcode:1921LAstr..35...89U. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ a b "The Real History of Animatronics". Rogers Studios. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ Bowles, Edmund A. (1953). "Instruments at the Court of Burgundy (1363–1467)". The Galpin Society Journal. 6: 41–51. doi:10.2307/841716. JSTOR 841716.

- ^ Sill, Christina Rose (2013-04-10). "A Survey of Androids and Audiences: 285 BCE to the Present Day" (PDF). Summit Research Repository. Simon Fraser University: 1, 16.

- ^ Moran, M. E. (December 2006). "The da Vinci robot". J. Endourol. 20 (12): 986–90. doi:10.1089/end.2006.20.986. PMID 17206888.

... the date of the design and possible construction of this robot was 1495 ... Beginning in the 1950s, investigators at the University of California began to ponder the significance of some of da Vinci's markings on what appeared to be technical drawings ... It is now known that da Vinci's robot would have had the outer appearance of a Germanic knight.

- ^ Shirbon, Estelle (August 14, 2009). "Da Vinci's lion prowls again after 500 years". Reuters. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- ^ "Clockwork Prayer: Introduction, Elizabeth King". blackbird-archive.vcu.edu. Retrieved 2024-01-25.

- ^ Molesworth (1914). The Cuckoo Clock. JB Lippincott Company. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ Kircher, Athanasius (1650). Musurgia Universalis sive Ars magna consoni & dissoni. Vol. 2. Rome. p. 343f and Plate XXI.

- ^ Miller, Justin (2012). Rare and Unusual Black Forest Clocks. Schiffer. p. 30.

- ^ Markowitz, Judith (2014). Robots that Talk and Listen: Technology and Social Impact. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 33. ISBN 9781614516033.

- ^ Duane P. Schultz; Sydney Ellen Schultz (2008). A History of Modern Psychology. Thompson Wadsworth. pp. 28–34.

- ^ Fryer, David M.; Marshall, John C. (1979). "The Motives of Jacques de Vaucanson". Technology and Culture. 20 (2): 257. doi:10.2307/3103866. JSTOR 3103866. S2CID 111617989.

- ^ a b c d Randi, James (1992). Conjuring. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-08634-2. OCLC 26162991.

- ^ "The Bowes Museum > Collections > Explore The Collection > The Silver Swan". www.thebowesmuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-12-11. Retrieved 2014-10-01.

- ^ Waddesdon Manor (22 July 2015). "A Marvellous Elephant – Waddesdon Manor" – via YouTube.

- ^ Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish, New York, Vintage Books, 1979, p.136: "The classical age discovered the body as object and target of power... The great book of Man-the-Machine was written simultaneously on two registers: the anatomico-metaphysical register, of which Descartes wrote the first pages and which the physicians and philosophers continued, and the technico-political register, which was constituted by a whole set of regulations and by empirical and calculated methods relating to the army, the school and the hospital, for controlling or correcting the operations of the body. These two registers are quite distinct, since it was a question, on one hand, of submission and use and, on the other, of functioning and explanation: there was a useful body and an intelligible body... The celebrated automata [of the 18th century] were not only a way of illustrating an organism, they were also political puppets, small-scale models of power: Frederick, the meticulous king of small machines, well-trained regiments and long exercises, was obsessed with them."

- ^ Kolesnikov-Jessop, Sonia (November 25, 2011). "Chinese Swept Up in Mechanical Mania". The New York Times. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

Mechanical curiosities were all the rage in China during the 18th and 19th centuries, as the Qing emperors developed a passion for automaton clocks and pocket watches, and the "Sing Song Merchants", as European watchmakers were called, were more than happy to encourage that interest.

- ^ Copperfield, David; Wiseman, Richard; Britland, David (2021). David Copperfield's history of magic. New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-9821-1291-2. OCLC 1236259508.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Keyser, Cheryl. "Fortune Telling Machines". Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ Mahoney, Michael S. "The Structures of Computation and the Mathematical Structure of Nature". The Rutherford Journal. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Artomic Automata". artomic.com. Archived from the original on 2010-03-05. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ^ "Biography, Sam Smith 1908–1983 | Sam Smith". 21 May 2013.

- ^ "Events: Sam Smith". 21 May 2013.

- ^ "H C Westermann/Sam Smith". Serpentine Galleries.

- ^ Hall, Loura (1 April 2016). "Automaton Rover for Extreme Environments (AREE)". NASA. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Wang, Jiacun (2019). Formal Methods in Computer Science. CRC Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4987-7532-8.

- ^ "How Do Cuckoo Clocks Work?". www.cuckooclocks.com. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ Munchow, Joshua (2020-07-19). "All About Automata: Mechanical Magic (With Action Videos)". Quill & Pad. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

Further reading

[edit]- Bailly, Christian (2003). Automata: The Golden Age: 1848–1914. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 9780709074038.

- Balafrej, Lamia (2022). "Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206". 21: Inquiries into Art, History, and the Visual. 3 (4): 737–774. doi:10.11588/xxi.2022.4.91685. ISSN 2701-1569.

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. III (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 142.

- Beyer, Annette (1983). Faszinierende Welt der Automaten : Uhren, Puppen, Spielereien (1st ed.). München: Callwey. ISBN 9783766706591.

- Bowers, Q. David (1974). Encyclopedia of Automatic Musical Instruments (4. printing ed.). Vestal, NY: Vestal Press. ISBN 9780911572087.

- Brauers, Jan (1984). Von der Äolsharfe zum Digitalspieler: 2000 Jahre mechanische Musik, 100 Jahre Schallplatte. München: Klinkhardt & Biermann. ISBN 9783781402393.

- Cardinal, Catherine; Mercier, François (1993). Museums of horology La Chaux-de-Fonds, Le Locle. Geneva: Banque Paribas. ISBN 9783908184348.

- Carrera, Roland; Loiseau, Dominique; Roux, Olivier; Luder, Jean Jacques (1979). Androids: The Jaquet-Droz Automatons. Lausanne: Scriptar. ISBN 9782880120184.

- Chapuis, Alfred; Droz, Edmond (1956). The Jaquet-Droz mechanical puppets. Neuchatel: Historical Museum. OCLC 315497609.

- Chapuis, Alfred; Gélis, Edouard (1928). Le monde des automates; étude historique et technique. OCLC 3006589.

- Critchley, Macdonald; Henson, R. A. (1978). Music and the brain. Studies in the neurology of music. London: Heinemann. ISBN 9780433067030.

- Hyman, Wendy Beth (2011). The Automaton in English Renaissance Literature. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6865-7.

- Lapaire, Claude (1992). Clock and Watch Museum, Geneva. Geneva: Art and History Museum. ISBN 9782830600728.

- Montiel, Luis (30 June 2013). "Proles sine matre creata: The Promethean Urge in the History of the Human Body in the West". Asclepio. 65 (1): 001. doi:10.3989/asclepio.2013.01.

- Ord-Hume, Arthur W. J. G. (1973). Clockwork music: an illustrated history of mechanical musical instruments from the music box to the pianola, from automation lady virginal players to orchestrion. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 9780517500002.

- Ord-Hume, Arthur W.J.G. (1978). Barrel organ: the story of the mechanical organ and its repair. South Brunswick, N.J.: A.S. Barnes. ISBN 9780498014826.

- Rausser, Fernand; Bonhôte, Daniel; Baud, Frédy (1972). All'Epoca delle Scatole Musicali, Edizioni Mondo, 175 pp.

- Troquet, Daniel (1989). The wonderland of music boxes and automata. Sainte-Croix. OCLC 27888631.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Waard, R. D. (1967). From music boxes to street organs. OCLC 609338403.

- Webb, Graham (1984). The musical box handbook (2nd ed.). Vestal, NY: Vestal Press. ISBN 9780911572360.

- Weiss-Stauffacher, Heinrich; Bruhin, Rudolf (1976). The marvelous world of music machines. Tokyo: Kodansha International. ISBN 9780870112584.

- Winter-Jensen, Anne (1987). Automates & musiques: pendules. Genève: Musée de l'horlogerie et de l'émaillerie. ISBN 9782830600476.

- Wosk, Julie (2015). My Fair Ladies: Female Robots, Androids, and Other Artificial Eves. ISBN 9780813563374.

External links

[edit]- The Automata and Art Bots mailing list home page Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- History

- Modern Automata Museum

- The House of Automata – The largest online gallery of automata

- Automata Magazine

- Maillardet's Automaton

- Japanese Karakuri Archived 2021-03-18 at the Wayback Machine

- J. Douglas Bruce, 'Human Automata in Classical Tradition and Mediaeval Romance', Modern Philology, Vol. 10, No. 4 (Apr., 1913), pp. 511–526

- M. B. Ogle, 'The Perilous Bridge and Human Automata', Modern Language Notes, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Mar., 1920), pp. 129–136

- conservation of automata

- Thomas Edison's talking doll

- Automata in the Waddesdon Manor collection

- Video of elephant automaton on YouTube

- Video of Catherine the Great's 'The Peacock Clock' on YouTube