Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

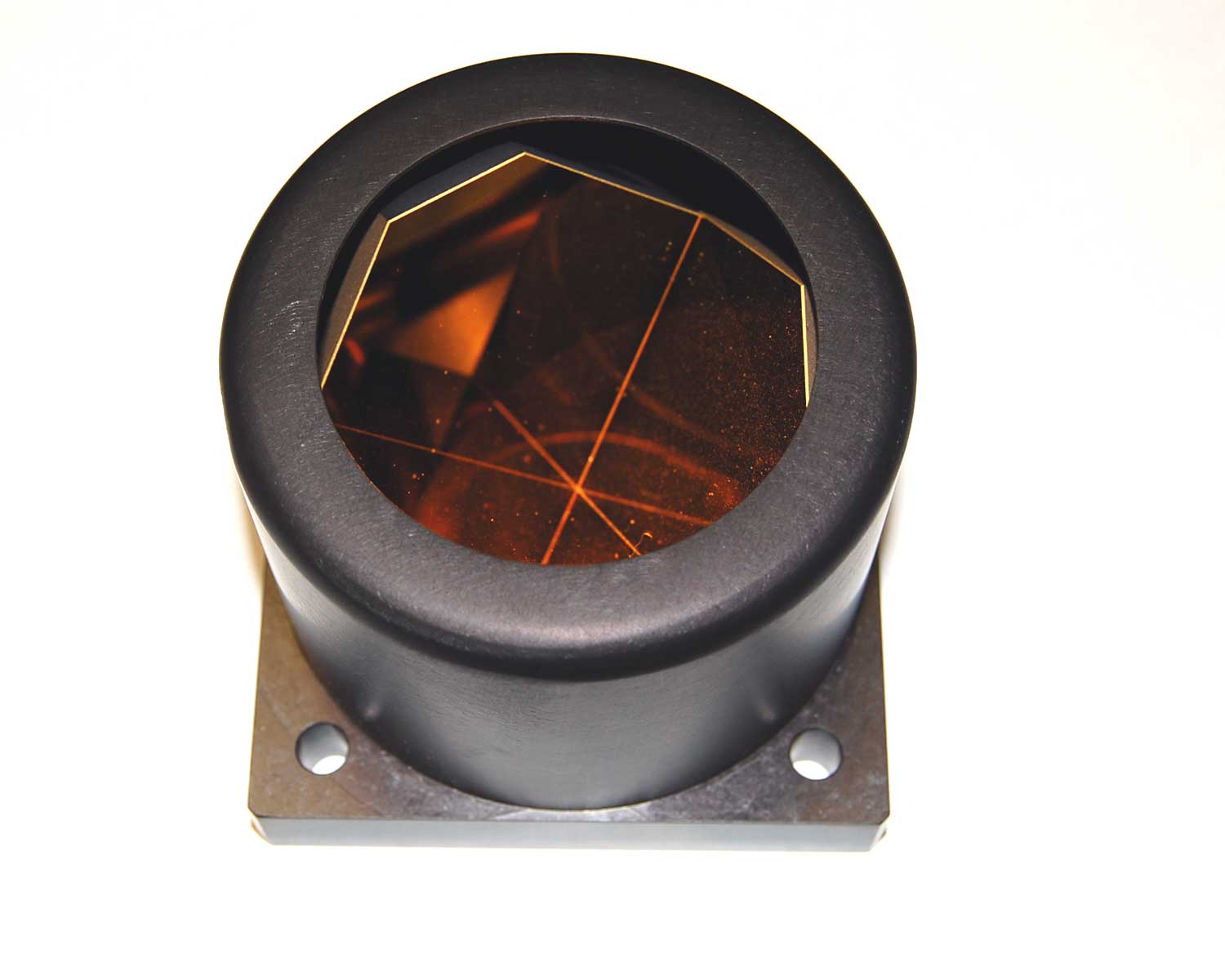

Retroreflector

View on Wikipedia A gold corner-cube retroreflector (made with three orthogonally joined flat mirrors) | |

| Uses | Distance measurement by optical delay line

High-visibility markings in low-light conditions |

|---|---|

A retroreflector (sometimes called a retroflector or cataphote) is a device or surface that reflects light or other radiation back to its source with minimum scattering. This works at a wide range of angle of incidence, unlike a planar mirror, which does this only if the mirror is exactly perpendicular to the wave front, having a zero angle of incidence. Being directed, the retroflector's reflection is brighter than that of a diffuse reflector. Corner reflectors and cat's eye reflectors are the most used kinds.

Types

[edit]There are several ways to obtain retroreflection:[1]

Corner reflector

[edit]

A set of three mutually perpendicular reflective surfaces, placed to form the internal corner of a cube, work as a retroreflector. The three corresponding normal vectors of the corner's sides form a basis (x, y, z) in which to represent the direction of an arbitrary incoming ray, [a, b, c]. When the ray reflects from the first side, say x, the ray's x-component, a, is reversed to −a, while the y- and z-components are unchanged. Therefore, as the ray reflects first from side x then side y and finally from side z the ray direction goes from [a, b, c] to [−a, b, c] to [−a, −b, c] to [−a, −b, −c] and it leaves the corner with all three components of its direction exactly reversed.

Corner reflectors occur in two varieties. In the more common form, the corner is literally the truncated corner of a cube of transparent material such as conventional optical glass. In this structure, the reflection is achieved either by total internal reflection or silvering of the outer cube surfaces. The second form uses mutually perpendicular flat mirrors bracketing an air space. These two types have similar optical properties.

A large relatively thin retroreflector can be formed by combining many small corner reflectors, using the standard hexagonal tiling.

Cat's eye

[edit]

Another common type of retroreflector consists of refracting optical elements with a reflective surface, arranged so that the focal surface of the refractive element coincides with the reflective surface, typically a transparent sphere and (optionally) a spherical mirror. In the paraxial approximation, this effect can be achieved with lowest divergence with a single transparent sphere when the refractive index of the material is exactly one plus the refractive index ni of the medium from which the radiation is incident (ni is around 1 for air). In that case, the sphere surface behaves as a concave spherical mirror with the required curvature for retroreflection. In practice, the optimal index of refraction may be lower than ni + 1 ≅ 2 due to several factors. For one, it is sometimes preferable to have an imperfect, slightly divergent retroreflection, as in the case of road signs, where the illumination and observation angles are different. Due to spherical aberration, there also exists a radius from the centerline at which incident rays are focused at the center of the rear surface of the sphere. Finally, high index materials have higher Fresnel reflection coefficients, so the efficiency of coupling of the light from the ambient into the sphere decreases as the index becomes higher. Commercial retroreflective beads thus vary in index from around 1.5 (common forms of glass) up to around 1.9 (commonly barium titanate glass).

The spherical aberration problem with the spherical cat's eye can be solved in various ways, one being a spherically symmetrical index gradient within the sphere, such as in the Luneburg lens design. Practically, this can be approximated by a concentric sphere system.[2]

Because the back-side reflection for an uncoated sphere is imperfect, it is fairly common to add a metallic coating to the back half of retroreflective spheres to increase the reflectance, but this implies that the retroreflection only works when the sphere is oriented in a particular direction.

An alternative form of the cat's eye retroreflector uses a normal lens focused onto a curved mirror rather than a transparent sphere, though this type is much more limited in the range of incident angles that it retroreflects.

The term cat's eye derives from the resemblance of the cat's eye retroreflector to the optical system that produces the well-known phenomenon of "glowing eyes" or eyeshine in cats and other vertebrates (which are only reflecting light, rather than actually glowing). The combination of the eye's lens and the cornea form the refractive converging system, while the tapetum lucidum behind the retina forms the spherical concave mirror. Because the function of the eye is to form an image on the retina, an eye focused on a distant object has a focal surface that approximately follows the reflective tapetum lucidum structure,[citation needed] which is the condition required to form a good retroreflection.

This type of retroreflector can consist of many small versions of these structures incorporated in a thin sheet or in paint. In the case of paint containing glass beads, the paint adheres the beads to the surface where retroreflection is required and the beads protrude, their diameter being about twice the thickness of the paint.

Phase-conjugate mirror

[edit]A third, much less common way of producing a retroreflector is to use the nonlinear optical phenomenon of phase conjugation. This technique is used in advanced optical systems such as high-power lasers and optical transmission lines. Phase-conjugate mirrors[3] reflect an incoming wave so that the reflected wave exactly follows the path it has previously taken, and require a comparatively expensive and complex apparatus, as well as large quantities of power (as nonlinear optical processes can be efficient only at high enough intensities). However, phase-conjugate mirrors have an inherently much greater accuracy in the direction of the retroreflection, which in passive elements is limited by the mechanical accuracy of the construction.

Operation

[edit]

Retroreflectors are devices that operate by returning light back to the light source along the same light direction. The coefficient of luminous intensity, RI, is the measure of a reflector performance, which is defined as the ratio of the strength of the reflected light (luminous intensity) to the amount of light that falls on the reflector (normal illuminance). A reflector appears brighter as its RI value increases.[1]

The RI value of the reflector is a function of the color, size, and condition of the reflector. Clear or white reflectors are the most efficient, and appear brighter than other colors. The surface area of the reflector is proportional to the RI value, which increases as the reflective surface increases.[1]

The RI value is also a function of the spatial geometry between the observer, light source, and reflector. Figures 1 and 2 show the observation angle and entrance angle between the automobile's headlights, bicycle, and driver. The observation angle is the angle formed by the light beam and the driver's line of sight. Observation angle is a function of the distance between the headlights and the driver's eye, and the distance to the reflector. Traffic engineers use an observation angle of 0.2 degrees to simulate a reflector target about 800 feet in front of a passenger automobile. As the observation angle increases, the reflector performance decreases. For example, a truck has a large separation between the headlight and the driver's eye compared to a passenger vehicle. A bicycle reflector appears brighter to the passenger car driver than to the truck driver at the same distance from the vehicle to the reflector.[1]

The light beam and the normal axis of the reflector as shown in Figure 2 form the entrance angle. The entrance angle is a function of the orientation of the reflector to the light source. For example, the entrance angle between an automobile approaching a bicycle at an intersection 90 degrees apart is larger than the entrance angle for a bicycle directly in front of an automobile on a straight road. The reflector appears brightest to the observer when it is directly in line with the light source.[1]

The brightness of a reflector is also a function of the distance between the light source and the reflector. At a given observation angle, as the distance between the light source and the reflector decreases, the light that falls on the reflector increases. This increases the amount of light returned to the observer and the reflector appears brighter.[1]

Applications

[edit]On roads

[edit]

Retroreflection (sometimes called retroflection) is used on road surfaces, road signs, vehicles, and clothing (large parts of the surface of special safety clothing, less on regular coats). When the headlights of a car illuminate a retroreflective surface, the reflected light is directed towards the car and its driver (rather than in all directions as with diffuse reflection). However, a pedestrian can see retroreflective surfaces in the dark only if there is a light source directly between them and the reflector (e.g., via a flashlight they carry) or directly behind them (e.g., via a car approaching from behind). "Cat's eyes" are a particular type of retroreflector embedded in the road surface and are used mostly in the UK and parts of the United States.

Corner reflectors are better at sending the light back to the source over long distances, while spheres are better at sending the light to a receiver somewhat off-axis from the source, as when the light from headlights is reflected into the driver's eyes.

Retroreflectors can be embedded in the road (level with the road surface), or they can be raised above the road surface. Raised reflectors are visible for very long distances (typically 0.5–1 kilometer or more), while sunken reflectors are visible only at very close ranges due to the higher angle required to properly reflect the light. Raised reflectors are generally not used in areas that regularly experience snow during winter, as passing snowplows can tear them off the roadways. Stress on roadways caused by cars running over embedded objects also contributes to accelerated wear and pothole formation.

Retroreflective road paint is thus very popular in Canada and parts of the United States, as it is not affected by the passage of snowplows and does not affect the interior of the roadway. Where weather permits, embedded or raised retroreflectors are preferred as they last much longer than road paint, which is weathered by the elements, can be obscured by sediment or rain, and is ground away by the passage of vehicles.

For signs

[edit]

For traffic signs and vehicle operators, the light source is a vehicle's headlights, where the light is sent to the traffic sign face and then returned to the vehicle operator. Retroreflective traffic sign faces are manufactured with glass beads or prismatic reflectors embedded in a base sheeting layer so that the face reflects light, therefore making the sign appear more bright and visible to the vehicle operator under darkened conditions. According to the United States National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the Traffic Safety Facts 2000 publication states the fatal crash rate is 3-4 times more likely during nighttime crashes than daytime incidents.

A misconception many people have is that retroreflectivity is only important during night-time travel. However, in recent years, more states and agencies require that headlights be turned on in inclement weather such as rain and snow. According to the United States Federal Highway Administration (FHWA): Approximately 24% of all vehicle accidents occur during adverse weather (rain, sleet, snow and fog). Rain conditions account for 47% of weather-related accidents. These statistics are based on 14-year averages from 1995 to 2008.

The FHWA's Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices requires that signs be either illuminated or made with retroreflective sheeting materials, and though most signs in the U.S. are made with retroreflective sheeting materials, they degrade over time. Until now, there has been little information available to determine how long the retroreflectivity lasts. The MUTCD now requires that agencies maintain traffic signs to a set of minimum levels but provide a variety of maintenance methods that agencies can use for compliance. The minimum retroreflectivity requirements do not imply that an agency must measure every sign. Rather, the new MUTCD language describes methods that agencies can use to maintain traffic sign retroreflectivity at or above the minimum levels.

In Canada, aerodrome lighting can be replaced by appropriately colored retroreflectors, the most important of which are the white retroreflectors that delineate the runway edges, and must be seen by aircraft equipped with landing lights up to 2 nautical miles away.[4]

Ships, boats, emergency gear

[edit]Retroflective tape is recognized and recommended by the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) because of its high reflectivity of both light and radar signals. Application to life rafts, personal flotation devices, and other safety gear makes it easy to locate people and objects in the water at night. When applied to boat surfaces it creates a larger radar signature—particularly for fiberglass boats, which produce very little radar reflection on their own. It conforms to International Maritime Organization regulation, IMO Res. A.658 (16) and meets U.S. Coast Guard specification 46 CFR Part 164, Subpart 164.018/5/0. Examples of commercially available products are 3M part numbers 3150A and 6750I, and Orafol Oralite FD1403.

Surveying

[edit]

In surveying, a retroreflector—usually referred to as a prism—is normally attached on a surveying pole and is used as a target for distance measurement, for example, a total station. The instrument operator or robot aims a laser beam at the retroreflector. The instrument measures the propagation time of the light and converts it to a distance. Prisms are used with survey and 3D point monitoring systems to measure changes in horizontal and vertical position of a point. Two prisms may also serve as targets for angle measurements, using total stations or simpler theodolites; this usage, reminiscent of the heliotrope, does not involve retroreflection per se, it only requires visibility by means of any source of illumination (such as the sun) for direct sighting to the center of the target prism as seen from the optical instrument.

In space

[edit]On the Moon

[edit]

Astronauts on the Apollo 11, 14, and 15 missions left retroreflectors on the Moon as part of the Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment. The Soviet Lunokhod 1 and Lunokhod 2 rovers also carried smaller arrays. Reflected signals were initially received from Lunokhod 1, but no return signals were detected from 1971 until 2010, at least in part due to some uncertainty in its location on the Moon. In 2010, it was found in Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter photographs and the retroreflectors have been used again. Lunokhod 2's array continues to return signals to Earth.[5] Even under good viewing conditions, only a single reflected photon is received every few seconds. This makes the job of filtering laser-generated photons from naturally occurring photons challenging.[6]

Vikram lander of Chandrayaan-3 left Laser Retroreflector Array (LRA) instrument supplied by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center as part of international collaboration with ISRO. On 12 December 2023, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter was successfully able to detect transmitted laser pulses from Vikram lander.[7]

On Mars

[edit]A similar device, the Laser Retroreflector Array (LaRA), has been incorporated in the Mars Perseverance rover. The retroreflector was designed by the National Institute for Nuclear Physics of Italy, which built the instrument on behalf of the Italian Space Agency.

In satellites

[edit]Many artificial satellites carry retroreflectors so they can be tracked from ground stations. Some satellites were built solely for laser ranging. LAGEOS, or Laser Geodynamics Satellites, are a series of scientific research satellites designed to provide an orbiting laser ranging benchmark for geodynamical studies of the Earth.[8] There are two LAGEOS spacecraft: LAGEOS-1[9] (launched in 1976), and LAGEOS-2 (launched in 1992). They use cube-corner retroreflectors made of fused silica glass. As of 2020, both LAGEOS spacecraft are still in service.[10] Three STARSHINE satellites equipped with retroreflectors were launched beginning in 1999. The LARES satellite was launched on February 13, 2012. (See also: List of laser ranging satellites.)

Other satellites include retroreflectors for orbit calibration[11] and orbit determination,[12] such as in satellite navigation (e.g., all Galileo satellites,[13] most GLONASS satellites,[14] IRNSS satellites,[15] BeiDou,[16] QZSS,[17] and two GPS satellites[18]) as well as in satellite gravimetry (GOCE[19]) satellite altimetry (e.g., TOPEX/Poseidon, Sentinel-3[20]). Retroreflectors can also be used for inter-satellite laser ranging instead of ground-tracking (e.g., GRACE-FO).[21]

The BLITS (Ball Lens In The Space) spherical retroreflector satellite was placed into orbit as part of a September 2009 Soyuz launch[22] by the Federal Space Agency of Russia with the assistance of the International Laser Ranging Service, an independent body originally organized by the International Association of Geodesy, the International Astronomical Union, and international committees.[23] The ILRS central bureau is located at the United States' Goddard Space Flight Center. The reflector, a type of Luneburg lens, was developed and manufactured by the Institute for Precision Instrument Engineering (IPIE) in Moscow. The mission was interrupted in 2013 after a collision with space debris.[24][25]

Free-space optical communication

[edit]Modulated retroreflectors, in which the reflectance is changed over time by some means, are the subject of research and development for free-space optical communications networks. The basic concept of such systems is that a low-power remote system, such as a sensor mote, can receive an optical signal from a base station and reflect the modulated signal back to the base station. Since the base station supplies the optical power, this allows the remote system to communicate without excessive power consumption. Modulated retroreflectors also exist in the form of modulated phase-conjugate mirrors (PCMs). In the latter case, a "time-reversed" wave is generated by the PCM with temporal encoding of the phase-conjugate wave (see, e.g., SciAm, Oct. 1990, "The Photorefractive Effect," David M. Pepper, et al.).

Inexpensive corner-aiming retroreflectors are used in user-controlled technology as optical datalink devices. Aiming is done at night, and the necessary retroreflector area depends on aiming distance and ambient lighting from street lamps. The optical receiver itself behaves as a weak retroreflector because it contains a large, precisely focused lens that detects illuminated objects in its focal plane. This allows aiming without a retroreflector for short ranges.

Other uses

[edit]

Retroreflectors are used in the following example applications:

- In common (non-SLR) digital cameras, the sensor system is often retroreflective. Researchers have used this property to demonstrate a system to prevent unauthorized photographs by detecting digital cameras and beaming a highly focused beam of light into the lens.[26]

- In movie screens to allow for high brilliance under dark conditions.[27]

- Digital compositing programs and chroma key environments use retroreflection to replace traditional lit backdrops in composite work as they provide a more solid color without requiring that the backdrop be lit separately.[28]

- In Longpath-DOAS systems retroreflectors are used to reflect the light emitted from a lightsource back into a telescope. It is then spectrally analyzed to obtain information about the trace gas content of the air between the telescope and the retro reflector.

- Barcode labels can be printed on retroreflective material to increase the range of scanning up to 50 feet.[29]

- In a form of 3D display; where a retro-reflective sheeting and a set of projectors is used to project stereoscopic images back to user's eye. The use of mobile projectors and positional tracking mounted on user's spectacles frame allows the illusion of a hologram to be created for computer generated imagery.[30][31][32]

- Flashlight fish of the family Anomalopidae have natural retroreflectors. See tapetum lucidum.

- High-visibility clothing, especially in the construction industry.

History

[edit]Many prey and predator animals have naturally retroreflective eyes by having a reflective layer called the Tapetum lucidum behind the retina, since this doubles the light that their retina receives.

Inspired by the natural world, the inventor of road 'cat's eyes' was Percy Shaw of Boothtown, Halifax, West Yorkshire, England. When the tram-lines were removed in the nearby suburb of Ambler Thorn, he realised that he had been using the polished steel rails to navigate at night.[33] The name "cat's eye" comes from Shaw's inspiration for the device: the eyeshine reflecting from the eyes of a cat. In 1934, he patented his invention (patents Nos. 436,290 and 457,536), and on 15 March 1935, founded Reflecting Roadstuds Limited in Halifax to manufacture the items.[34][35] The name Catseye is their trademark.[36] The retroreflecting lens had been invented six years earlier for use in advertising signs by Richard Hollins Murray, an accountant from Herefordshire[37][38] and, as Shaw acknowledged, they had contributed to his idea.[33]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Bicycle Reflector Project report Archived 2007-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bernacki, Bruce E.; Anheier, Norman C.; Krishnaswami, Kannan; Cannon, Bret D.; Binkley, K. Brent (2008). "Design and fabrication of effi cient miniature retroreflectors for the mid-infrared". SPIE Defense & Security Conference 2008, Infrared Technology and Applications. Proc. SPIE 6940. XXXIV (30).

- ^ Gower, M.C. (1984). "The Physics of Phase Conjugate Mirrors". Progress in Quantum Electronics. 9 (2). Elsevier B.V.: 101–147. Bibcode:1984PQE.....9..101G. doi:10.1016/0079-6727(84)90023-5. ISSN 0079-6727.

- ^ "Transport Canada CARs 301.07". tc.gc.ca. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ NASA.gov

- ^ "NASA - Accuracy of Eclipse Predictions". eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2015-08-15.

- ^ "NASA spacecraft pings India's Chandrayaan-3 lander on the moon". The Hindu. 2024-01-19. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ Pearlman, M.; Arnold, D.; Davis, M.; Barlier, F.; Biancale, R.; Vasiliev, V.; Ciufolini, I.; Paolozzi, A.; Pavlis, E. C.; Sośnica, K.; Bloßfeld, M. (November 2019). "Laser geodetic satellites: a high-accuracy scientific tool". Journal of Geodesy. 93 (11): 2181–2194. Bibcode:2019JGeod..93.2181P. doi:10.1007/s00190-019-01228-y. S2CID 127408940.

- ^ NASA.gov

- ^ Zajdel, R.; Sośnica, K.; Drożdżewski, M.; Bury, G.; Strugarek, D. (November 2019). "Impact of network constraining on the terrestrial reference frame realization based on SLR observations to LAGEOS". Journal of Geodesy. 93 (11): 2293–2313. Bibcode:2019JGeod..93.2293Z. doi:10.1007/s00190-019-01307-0.

- ^ Kazmierski, Kamil; Sośnica, Krzysztof; Hadas, Tomasz (2017-11-06). "Quality assessment of multi-GNSS orbits and clocks for real-time precise point positioning". GPS Solutions. 22 (1): 11. Bibcode:2018GPSS...22...11K. doi:10.1007/s10291-017-0678-6.

- ^ Bury, Grzegorz; Sośnica, Krzysztof; Zajdel, Radosław (2018-04-19). "Multi-GNSS orbit determination using satellite laser ranging". Journal of Geodesy. 93 (12): 2447–2463. Bibcode:2019JGeod..93.2447B. doi:10.1007/s00190-018-1143-1.

- ^ Sośnica, Krzysztof; Prange, Lars; Kaźmierski, Kamil; Bury, Grzegorz; Drożdżewski, Mateusz; Zajdel, Radosław; Hadas, Tomasz (February 2018). "Validation of Galileo orbits using SLR with a focus on satellites launched into incorrect orbital planes". Journal of Geodesy. 92 (2): 131–148. Bibcode:2018JGeod..92..131S. doi:10.1007/s00190-017-1050-x.

- ^ Zajdel, Radosław (14 October 2017). "A New Online Service for the Validation of Multi-GNSS Orbits Using SLR". Remote Sensing. 9 (10): 1049. Bibcode:2017RemS....9.1049Z. doi:10.3390/rs9101049.

- ^ "IRNSS: Reflector Information". ilrs.cddis.eosdis.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-03-25. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ Sośnica, Krzysztof; Zajdel, Radosław; Bury, Grzegorz; Bosy, Jarosław; Moore, Michael; Masoumi, Salim (April 2020). "Quality assessment of experimental IGS multi-GNSS combined orbits". GPS Solutions. 24 (2): 54. Bibcode:2020GPSS...24...54S. doi:10.1007/s10291-020-0965-5.

- ^ Sośnica, K.; Bury, G.; Zajdel, R.; Strugarek, D.; Drożdżewski, M.; Kazmierski, K. (December 2019). "Estimating global geodetic parameters using SLR observations to Galileo, GLONASS, BeiDou, GPS, and QZSS". Earth, Planets and Space. 71 (1): 20. Bibcode:2019EP&S...71...20S. doi:10.1186/s40623-019-1000-3.

- ^ Sośnica, Krzysztof; Thaller, Daniela; Dach, Rolf; Steigenberger, Peter; Beutler, Gerhard; Arnold, Daniel; Jäggi, Adrian (July 2015). "Satellite laser ranging to GPS and GLONASS". Journal of Geodesy. 89 (7): 725–743. Bibcode:2015JGeod..89..725S. doi:10.1007/s00190-015-0810-8.

- ^ Strugarek, Dariusz; Sośnica, Krzysztof; Jäggi, Adrian (January 2019). "Characteristics of GOCE orbits based on Satellite Laser Ranging". Advances in Space Research. 63 (1): 417–431. Bibcode:2019AdSpR..63..417S. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2018.08.033. S2CID 125791718.

- ^ Strugarek, Dariusz; Sośnica, Krzysztof; Arnold, Daniel; Jäggi, Adrian; Zajdel, Radosław; Bury, Grzegorz; Drożdżewski, Mateusz (30 September 2019). "Determination of Global Geodetic Parameters Using Satellite Laser Ranging Measurements to Sentinel-3 Satellites". Remote Sensing. 11 (19): 2282. Bibcode:2019RemS...11.2282S. doi:10.3390/rs11192282.

- ^ Schwarz, Oliver (2016-01-21). "GRACE FO Laser Ranging Interferometer". SpaceTech GmbH. Archived from the original on 2019-12-06. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly; Günes, S. (2007-04-25). "Space exploration in 2009". RussianSpaceWeb.com. Archived from the original on 2024-01-15. Retrieved 2024-01-15.

- ^ Tyahla, Lori J. (2013-02-20). "ILRS Missions: BLITS". International Laser Ranging Service. Archived from the original on 2013-02-20. Retrieved 2013-02-20.

- ^ "BLITS (Ball Lens In The Space)". ESA, Earth Observation portal.

- ^ Blau, Patrick (2013-03-09). "Russian BLITS Satellite hit by Space Debris". Spaceflight101: Space News and Beyond. Archived from the original on 2016-10-05. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ Eng, Paul (2005-09-19). "Device Seeks to Jam Covert Digital Photographers". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2024-01-20. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- ^ Harris, William; Lamb, Robert (2005-07-20). "How Does an Invisibility Cloak Work?". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on 2023-09-21. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- ^ Thomas, Graham (2009-12-06). "Making things Vanish - The Truematte Technology". BBC. Archived from the original on 2017-07-05. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ^ Thermal, Timmy (2014-07-08). "Retroreflective Labels". Midcom Data Technologies, Inc. Archived from the original on 2023-09-25. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ^ "Design of an ultra-light head-mounted projective display (HMPD) and its applications in augmented collaborative environments" (PDF). Proceedings of SPIE. 2002.

- ^ "Retroreflective light field display". US Patent & Trademark Office. 2016-09-22.

- ^ "castAR Test Footage - Flight Simulator". YouTube. 2013-09-26. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11.

- ^ a b "The day Percy saw the light!". Halifax Today. Archived from the original on 12 March 2004. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "History". Reflecting Roadstuds Ltd. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Reyburn, Ross (1999-06-26). "Inventions that prove size doesn't matter; Ross Reyburn takes a look at some of the little things that have changed lives in big ways over the century". The Free Library. The Birmingham Post. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- ^ The History of British Roadsigns, Department for Transport, 2nd Edition, 1999

- ^ British patent 289619 7 April 1927

- ^ United States patent 1625905 Archived 2020-05-26 at the Wayback Machine 26 April 1927

References

[edit]- Optics Letters, Vol. 4, pp. 190–192 (1979), "Retroreflective Arrays as Approximate Phase Conjugators," by H.H. Barrett and S.F. Jacobs.

- Optical Engineering, Vol. 21, pp. 281–283 (March/April 1982), "Experiments with Retrodirective Arrays," by Stephen F. Jacobs.

- Scientific American, December 1985, "Phase Conjugation," by Vladimir Shkunov and Boris Zel'dovich.

- Scientific American, January 1986, "Applications of Optical Phase Conjugation," by David M. Pepper.

- Scientific American, April 1986, "The Amateur Scientist" ('Wonders with the Retroreflector'), by Jearl Walker.

- Scientific American, October 1990, "The Photorefractive Effect," by David M. Pepper, Jack Feinberg, and Nicolai V. Kukhtarev.