Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Astronaut

View on Wikipedia

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek ἄστρον (astron), meaning 'star', and ναύτης (nautes), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spacecraft. Although generally reserved for professional space travelers, the term is sometimes applied to anyone who travels into space, including scientists, politicians, journalists, and space tourists.[1][2]

"Astronaut" technically applies to all human space travelers regardless of nationality. However, astronauts fielded by Russia or the Soviet Union are typically known instead as cosmonauts (from the Russian "kosmos" (космос), meaning "space", also borrowed from Greek κόσμος).[3] Comparatively recent developments in crewed spaceflight made by China have led to the rise of the term taikonaut (from the Mandarin "tàikōng" (太空), meaning "space"), although its use is somewhat informal and its origin is unclear. In China, the People's Liberation Army Astronaut Corps astronauts and their foreign counterparts are all officially called hángtiānyuán (航天员, meaning "celestial navigator" or literally "heaven-sailing staff").

Since 1961 and as of 2021, 600 astronauts have flown in space.[4] Until 2002, astronauts were sponsored and trained exclusively by governments, either by the military or by civilian space agencies. With the suborbital flight of the privately funded SpaceShipOne in 2004, a new category of astronaut was created: the commercial astronaut.

Definition

[edit]

The criteria for what constitutes human spaceflight vary, with some focus on the point where the atmosphere becomes so thin that centrifugal force, rather than aerodynamic force, carries a significant portion of the weight of the flight object. The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) Sporting Code for astronautics recognizes only flights that exceed the Kármán line, at an altitude of 100 kilometers (62 mi).[5] In the United States, professional, military, and commercial astronauts who travel above an altitude of 80 kilometres (50 mi)[6] are awarded astronaut wings.

As of 17 November 2016[update], 552 people from 36 countries have reached 100 km (62 mi) or more in altitude, of whom 549 reached low Earth orbit or beyond.[7] Of these, 24 people have traveled beyond low Earth orbit, either to lunar orbit, the lunar surface, or, in one case, a loop around the Moon.[note 1] Three of the 24—Jim Lovell, John Young and Eugene Cernan—did so twice.[8]

As of 17 November 2016[update], under the U.S. definition, 558 people qualify as having reached space, above 50 miles (80 km) altitude. Of eight X-15 pilots who exceeded 50 miles (80 km) in altitude, only one, Joseph A. Walker, exceeded 100 kilometers (about 62.1 miles) and he did it two times, becoming the first person in space twice.[7] Space travelers have spent over 41,790 man-days (114.5-man-years) in space, including over 100 astronaut-days of spacewalks.[9][10] As of 2024[update], the man with the longest cumulative time in space is Oleg Kononenko, who has spent over 1100 days in space.[11] Peggy A. Whitson holds the record for the most time in space by a woman, at 675 days.[12]

Terminology

[edit]In 1959, when both the United States and Soviet Union were planning, but had yet to launch humans into space, NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan and his Deputy Administrator, Hugh Dryden, discussed whether spacecraft crew members should be called astronauts or cosmonauts. Dryden preferred "cosmonaut", on the grounds that flights would occur in and to the broader cosmos, while the "astro" prefix suggested flight specifically to the stars.[13] Most NASA Space Task Group members preferred "astronaut", which survived by common usage as the preferred American term.[14] When the Soviet Union launched the first man into space, Yuri Gagarin in 1961, they chose a term which anglicizes to "cosmonaut".[15][16]

Astronaut

[edit]

A professional space traveler is called an astronaut.[17] The first known use of the term "astronaut" in the modern sense was by Neil R. Jones in his 1930 short story "The Death's Head Meteor". The word itself had been known earlier; for example, in Percy Greg's 1880 book Across the Zodiac, "astronaut" referred to a spacecraft. In Les Navigateurs de l'infini (1925) by J.-H. Rosny aîné, the word astronautique (astronautics) was used. The word may have been inspired by "aeronaut", an older term for an air traveler first applied in 1784 to balloonists. An early use of "astronaut" in a non-fiction publication is Eric Frank Russell's poem "The Astronaut", appearing in the November 1934 Bulletin of the British Interplanetary Society.[18]

The first known formal use of the term astronautics in the scientific community was the establishment of the annual International Astronautical Congress in 1950, and the subsequent founding of the International Astronautical Federation the following year.[19]

NASA applies the term astronaut to any crew member aboard NASA spacecraft bound for Earth orbit or beyond. NASA also uses the term as a title for those selected to join its Astronaut Corps.[20] The European Space Agency similarly uses the term astronaut for members of its Astronaut Corps.[21]

Cosmonaut

[edit]

By convention, an astronaut employed by the Russian Federal Space Agency (or its predecessor, the Soviet space program) is called a cosmonaut in English texts.[20] The word is an Anglicization of kosmonavt (Russian: космонавт Russian pronunciation: [kəsmɐˈnaft]).[22] Other countries of the former Eastern Bloc use variations of the Russian kosmonavt, such as the Polish: kosmonauta (although Poles also used astronauta, and the two words are considered synonyms).[23]

Coinage of the term космонавт has been credited to Soviet aeronautics (or "cosmonautics") pioneer Mikhail Tikhonravov (1900–1974).[15][16] The first cosmonaut was Soviet Air Force pilot Yuri Gagarin, also the first person in space. He was part of the first six Soviet citizens, with German Titov, Yevgeny Khrunov, Andriyan Nikolayev, Pavel Popovich, and Grigoriy Nelyubov, who were given the title of pilot-cosmonaut in January 1961.[24] Valentina Tereshkova was the first female cosmonaut and the first and youngest woman to have flown in space with a solo mission on the Vostok 6 in 1963.[25] On 14 March 1995,[26] Norman Thagard became the first American to ride to space on board a Russian launch vehicle, and thus became the first "American cosmonaut".[27][28]

Taikonaut

[edit]

In Chinese, the term Yǔ háng yuán (宇航员, "cosmos navigating personnel") is used for astronauts and cosmonauts in general,[29][30] while hángtiān yuán (航天员, "navigating celestial-heaven personnel") is used for Chinese astronauts. Here, hángtiān (航天, literally "heaven-navigating", or spaceflight) is strictly[31] defined as the navigation of outer space within the local star system, i.e. Solar System. The phrase tàikōng rén (太空人, "spaceman") is often used in Hong Kong and Taiwan.[32]

The term taikonaut is used by some English-language news media organizations for professional space travelers from China.[33] The word has featured in the Longman and Oxford English dictionaries, and the term became more common in 2003 when China sent its first astronaut Yang Liwei into space aboard the Shenzhou 5 spacecraft.[34] This is the term used by Xinhua News Agency in the English version of the Chinese People's Daily since the advent of the Chinese space program.[35] The origin of the term is unclear; as early as May 1998, Chiew Lee Yih (趙裡昱) from Malaysia used it in newsgroups.[36][37][non-primary source needed]

Other terms

[edit]With the rise of space tourism, NASA and the Russian Federal Space Agency agreed to use the term "spaceflight participant" to distinguish those space travelers from professional astronauts on missions coordinated by those two agencies.

While no nation other than Russia (and previously the Soviet Union), the United States, and China have launched a crewed spacecraft, several other nations have sent people into space in cooperation with one of these countries, e.g. the Soviet-led Interkosmos program. Inspired partly by these missions, other synonyms for astronaut have entered occasional English usage. For example, the term spationaut (French: spationaute) is sometimes used to describe French space travelers, from the Latin word spatium for "space"; the Malay term angkasawan (deriving from angkasa meaning 'space') was used to describe participants in the Angkasawan program (note its similarity with the Indonesian term antariksawan). Plans of the Indian Space Research Organisation to launch its crewed Gaganyaan spacecraft have spurred at times public discussion if another term than astronaut should be used for the crew members, suggesting vyomanaut (from the Sanskrit word vyoman meaning 'sky' or 'space') or gagannaut (from the Sanskrit word gagan for 'sky').[38][39] In Finland, the NASA astronaut Timothy Kopra, a Finnish American, has sometimes been referred to as sisunautti, from the Finnish word sisu.[40] Across Germanic languages, the word for "astronaut" typically translates to "space traveler", as it does with German's Raumfahrer, Dutch's ruimtevaarder, Swedish's rymdfarare, and Norwegian's romfarer.

For its 2022 Astronaut Group, the European Space Agency envisioned recruiting an astronaut with a physical disability, a category they called "parastronauts", with the intention but not guarantee of spaceflight.[41] The categories of disability considered for the program were individuals with lower limb deficiency (either through amputation or congenital), leg length difference, or a short stature (less than 130 centimetres or 4 feet 3 inches).[42] On 23 November 2022, John McFall was selected to be the first ESA parastronaut;[43] he has rejected the use of the term.[44]

As of 2021 in the United States, astronaut status is conferred on a person depending on the authorizing agency:

- one who flies in a vehicle above 50 miles (80 km) for NASA or the military is considered an astronaut (with no qualifier)

- one who flies in a vehicle to the International Space Station in a mission coordinated by NASA and Roscosmos is a spaceflight participant

- one who flies above 50 miles (80 km) in a non-NASA vehicle as a crewmember and demonstrates activities during flight that are essential to public safety, or contribute to human space flight safety, is considered a commercial astronaut by the Federal Aviation Administration[45]

- one who flies to the International Space Station as part of a "privately funded, dedicated commercial spaceflight on a commercial launch vehicle dedicated to the mission ... to conduct approved commercial and marketing activities on the space station (or in a commercial segment attached to the station)" is considered a private astronaut by NASA[46] (as of 2020, nobody has yet qualified for this status)

On July 20, 2021, the FAA issued an order redefining the eligibility criteria to be an astronaut in response to the private suborbital spaceflights of Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson.[47][48] The new criteria states that one must have "[d]emonstrated activities during flight that were essential to public safety, or contributed to human space flight safety" to qualify as an astronaut. This new definition excludes Bezos and Branson.

Space travel milestones

[edit]

The first human in space was Soviet Yuri Gagarin, who was launched on 12 April 1961, aboard Vostok 1 and orbited around the Earth for 108 minutes. The first woman in space was Soviet Valentina Tereshkova, who launched on 16 June 1963, aboard Vostok 6 and orbited Earth for almost three days.

Alan Shepard became the first American and second person in space on 5 May 1961, on a 15-minute sub-orbital flight aboard Freedom 7. The first American to orbit the Earth was John Glenn, aboard Friendship 7 on 20 February 1962. The first American woman in space was Sally Ride, during Space Shuttle Challenger's mission STS-7, on 18 June 1983.[49] In 1992, Mae Jemison became the first African American woman to travel in space aboard STS-47.

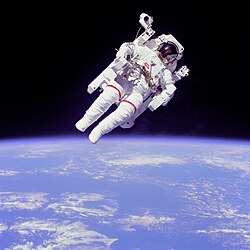

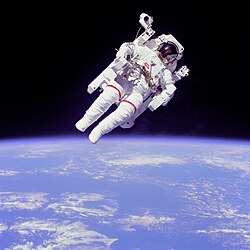

Cosmonaut Alexei Leonov was the first person to conduct an extravehicular activity (EVA), (commonly called a "spacewalk"), on 18 March 1965, on the Soviet Union's Voskhod 2 mission. This was followed two and a half months later by astronaut Ed White who made the first American EVA on NASA's Gemini 4 mission.[50]

The first crewed mission to orbit the Moon, Apollo 8, included American William Anders who was born in Hong Kong, making him the first Asian-born astronaut in 1968.

The Soviet Union, through its Intercosmos program, allowed people from multiple other countries, mostly Soviet-allied but also including from France and Austria, to participate in Soyuz TM-7 and Soyuz TM-13, respectively. This made the Czechoslovak Vladimír Remek the first cosmonaut/astronaut from a country other than the Soviet Union or the United States to fly to space in 1978 on a Soyuz-U rocket.[51]

On 23 July 1980, Pham Tuan of Vietnam became the first Asian in space when he flew aboard Soyuz 37.[52] Also in 1980, Cuban Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez became the first person of black African descent, as well as the first Hispanic astronaut. In 1983, Guion Bluford became the first African American to fly into space. In April 1985, the Taiwanese-American Taylor Wang became the first ethnic Chinese person in space.[53][54]

With the increase of seats on the Space Shuttle, the U.S. also began taking international astronauts. In 1983, Ulf Merbold of West Germany became the first non-US citizen to fly in a US spacecraft. In 1984, Marc Garneau became the first of eight Canadian astronauts to fly in space (through 2010).[55] The first person born in Africa to fly in space was Patrick Baudry of France, in 1985.[56][57] In same NASA flight as the Frenchman was the Saudi Arabian Prince Sultan Bin Salman Bin AbdulAziz Al-Saud, who became the first Muslim and Arab astronaut.[58] In 1985, Rodolfo Neri Vela became the first Mexican-born person in space.[59] In 1991, Helen Sharman became the first Briton to fly in space.[60]

In 2001, American Dennis Tito became the first space tourist, after paying a fee for a trip aboard Russian spacecraft Soyuz. In 2002, another private tourist, the South African Mark Shuttleworth, became the first citizen of an African country to fly into space.[61]

On 15 October 2003, Yang Liwei became China's first astronaut on its own spacecraft, the Shenzhou 5.

Age milestones

[edit]The youngest person to reach space is Oliver Daemen, who was 18 years and 11 months old when he made a suborbital spaceflight on Blue Origin NS-16.[62] Daemen, who was a commercial passenger aboard the New Shepard, broke the record of Soviet cosmonaut Gherman Titov, who was 25 years old when he flew Vostok 2. Titov remains the youngest human to reach orbit; he rounded the planet 17 times. Titov was also the first person to suffer space sickness and the first person to sleep in space, twice.[63][64]

The oldest person to reach space is William Shatner, who was 90 years old when he made a suborbital spaceflight on Blue Origin NS-18.[65] The oldest person to reach orbit is John Glenn, one of the Mercury 7, who was 77 when he flew on STS-95.[66]

Duration and distance milestones

[edit]The longest time spent in space was by Russian Valeri Polyakov, who spent 438 days there.[9] As of 2006, the most spaceflights by an individual astronaut is seven, a record held by both Jerry L. Ross and Franklin Chang-Diaz. The farthest distance from Earth an astronaut has traveled was 401,056 km (249,205 mi), when Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise went around the Moon during the Apollo 13 emergency.[9]

Civilian and non-government milestones

[edit]The first civilian in space was Valentina Tereshkova[67] aboard Vostok 6 (she also became the first woman in space on that mission). Tereshkova was only honorarily inducted into the USSR's Air Force, which did not accept female pilots at that time. A month later, Joseph Albert Walker became the first American civilian in space when his X-15 Flight 90 crossed the 100 kilometers (54 nautical miles) line, qualifying him by the international definition of spaceflight.[68][69] Walker had joined the US Army Air Force but was not a member during his flight. The first people in space who had never been a member of any country's armed forces were both Konstantin Feoktistov and Boris Yegorov aboard Voskhod 1.

The first non-governmental space traveler was Byron K. Lichtenberg, a researcher from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who flew on STS-9 in 1983.[70] In December 1990, Toyohiro Akiyama became the first paying space traveler and the first journalist in space for Tokyo Broadcasting System, a visit to Mir as part of an estimated $12 million (USD) deal with a Japanese TV station, although at the time, the term used to refer to Akiyama was "Research Cosmonaut".[71][72][73] Akiyama suffered severe space sickness during his mission, which affected his productivity.[72]

The first self-funded space tourist was Dennis Tito on board the Russian spacecraft Soyuz TM-3 on 28 April 2001.

Self-funded travelers

[edit]The first person to fly on an entirely privately funded mission was Mike Melvill, piloting SpaceShipOne flight 15P on a suborbital journey, although he was a test pilot employed by Scaled Composites and not an actual paying space tourist.[74][75] Jared Isaacman was the first person to self-fund a mission to orbit, commanding Inspiration4 in 2021.[76] Nine others have paid Space Adventures to fly to the International Space Station:

- Dennis Tito (American): 28 April – 6 May 2001

- Mark Shuttleworth (South African): 25 April – 5 May 2002

- Gregory Olsen (American): 1–11 October 2005

- Anousheh Ansari (Iranian / American): 18–29 September 2006

- Charles Simonyi (Hungarian / American): 7–21 April 2007, 26 March – 8 April 2009

- Richard Garriott (British / American): 12–24 October 2008

- Guy Laliberté (Canadian): 30 September 2009 – 11 October 2009

- Yusaku Maezawa and Yozo Hirano (both Japanese): 8 – 24 December 2021

Training

[edit]

The first NASA astronauts were selected for training in 1959.[77] Early in the space program, military jet test piloting and engineering training were often cited as prerequisites for selection as an astronaut at NASA, although neither John Glenn nor Scott Carpenter (of the Mercury Seven) had any university degree, in engineering or any other discipline at the time of their selection. Selection was initially limited to military pilots.[78][79] The earliest astronauts for both the US and the USSR tended to be jet fighter pilots, and were often test pilots.

Once selected, NASA astronauts go through twenty months of training in a variety of areas, including training for extravehicular activity in a facility such as NASA's Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory.[1][78] Astronauts-in-training (astronaut candidates) may also experience short periods of weightlessness (microgravity) in an aircraft called the "Vomit Comet," the nickname given to a pair of modified KC-135s (retired in 2000 and 2004, respectively, and replaced in 2005 with a C-9) which perform parabolic flights.[77] Astronauts are also required to accumulate a number of flight hours in high-performance jet aircraft. This is mostly done in T-38 jet aircraft out of Ellington Field, due to its proximity to the Johnson Space Center. Ellington Field is also where the Shuttle Training Aircraft is maintained and developed, although most flights of the aircraft are conducted from Edwards Air Force Base.

Astronauts in training must learn how to control and fly the Space Shuttle; further, it is vital that they are familiar with the International Space Station so they know what they must do when they get there.[80]

NASA candidacy requirements

[edit]- The candidate must be a citizen of the United States.

- The candidate must complete a master's degree in a STEM field, including engineering, biological science, physical science, computer science or mathematics.

- The candidate must have at least two years of related professional experience obtained after degree completion or at least 1,000 hours pilot-in-command time on jet aircraft.

- The candidate must be able to pass the NASA long-duration flight astronaut physical.

- The candidate must also have skills in leadership, teamwork and communications.

The master's degree requirement can also be met by:

- Two years of work toward a doctoral program in a related science, technology, engineering or math field.

- A completed Doctor of Medicine or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine degree.

- Completion of a nationally recognized test pilot school program.

Mission Specialist Educator

[edit]- Applicants must have a bachelor's degree with teaching experience, including work at the kindergarten through twelfth grade level. An advanced degree, such as a master's degree or a doctoral degree, is not required, but is strongly desired.[81]

Mission Specialist Educators, or "Educator Astronauts", were first selected in 2004; as of 2007, there are three NASA Educator astronauts: Joseph M. Acaba, Richard R. Arnold, and Dorothy Metcalf-Lindenburger.[82][83] Barbara Morgan, selected as back-up teacher to Christa McAuliffe in 1985, is considered to be the first Educator astronaut by the media, but she trained as a mission specialist.[84] The Educator Astronaut program is a successor to the Teacher in Space program from the 1980s.[85][86]

Health risks of space travel

[edit]

Astronauts are susceptible to a variety of health risks including decompression sickness, barotrauma, immunodeficiencies, loss of bone and muscle, loss of eyesight, orthostatic intolerance, sleep disturbances, and radiation injury.[87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96] A variety of large scale medical studies are being conducted in space via the National Space Biomedical Research Institute (NSBRI) to address these issues. Prominent among these is the Advanced Diagnostic Ultrasound in Microgravity Study in which astronauts (including former ISS commanders Leroy Chiao and Gennady Padalka) perform ultrasound scans under the guidance of remote experts to diagnose and potentially treat hundreds of medical conditions in space. This study's techniques are now being applied to cover professional and Olympic sports injuries as well as ultrasound performed by non-expert operators in medical and high school students. It is anticipated that remote guided ultrasound will have application on Earth in emergency and rural care situations, where access to a trained physician is often rare.[97][98][99]

A 2006 Space Shuttle experiment found that Salmonella typhimurium, a bacterium that can cause food poisoning, became more virulent when cultivated in space.[100] More recently, in 2017, bacteria were found to be more resistant to antibiotics and to thrive in the near-weightlessness of space.[101] Microorganisms have been observed to survive the vacuum of outer space.[102][103]

On 31 December 2012, a NASA-supported study reported that human spaceflight may harm the brain and accelerate the onset of Alzheimer's disease.[104][105][106]

In October 2015, the NASA Office of Inspector General issued a health hazards report related to space exploration, including a human mission to Mars.[107][108]

Over the last decade, flight surgeons and scientists at NASA have seen a pattern of vision problems in astronauts on long-duration space missions. The syndrome, known as visual impairment intracranial pressure (VIIP), has been reported in nearly two-thirds of space explorers after long periods spent aboard the International Space Station (ISS).[109]

On 2 November 2017, scientists reported that significant changes in the position and structure of the brain have been found in astronauts who have taken trips in space, based on MRI studies. Astronauts who took longer space trips were associated with greater brain changes.[110][111]

Being in space can be physiologically deconditioning on the body. It can affect the otolith organs and adaptive capabilities of the central nervous system. Zero gravity and cosmic rays can cause many implications for astronauts.[112]

In October 2018, NASA-funded researchers found that lengthy journeys into outer space, including travel to the planet Mars, may substantially damage the gastrointestinal tissues of astronauts. The studies support earlier work that found such journeys could significantly damage the brains of astronauts, and age them prematurely.[113]

Researchers in 2018 reported, after detecting the presence on the International Space Station (ISS) of five Enterobacter bugandensis bacterial strains, none pathogenic to humans, that microorganisms on ISS should be carefully monitored to continue assuring a medically healthy environment for astronauts.[114][115]

A study by Russian scientists published in April 2019 stated that astronauts facing space radiation could face temporary hindrance of their memory centers. While this does not affect their intellectual capabilities, it temporarily hinders formation of new cells in brain's memory centers. The study conducted by Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT) concluded this after they observed that mice exposed to neutron and gamma radiation did not impact the rodents' intellectual capabilities.[116]

A 2020 study conducted on the brains of eight male Russian cosmonauts after they returned from long stays aboard the International Space Station showed that long-duration spaceflight causes many physiological adaptions, including macro- and microstructural changes. While scientists still know little about the effects of spaceflight on brain structure, this study showed that space travel can lead to new motor skills (dexterity), but also slightly weaker vision, both of which could possibly be long lasting. It was the first study to provide clear evidence of sensorimotor neuroplasticity, which is the brain's ability to change through growth and reorganization.[117][118]

Food and drink

[edit]

An astronaut on the International Space Station requires about 830 g (29 oz) mass of food per meal each day (inclusive of about 120 g or 4.2 oz packaging mass per meal).

Space Shuttle astronauts worked with nutritionists to select menus that appealed to their individual tastes. Five months before flight, menus were selected and analyzed for nutritional content by the shuttle dietician. Foods are tested to see how they will react in a reduced gravity environment. Caloric requirements are determined using a basal energy expenditure (BEE) formula. On Earth, the average American uses about 35 US gallons (130 L) of water every day. On board the ISS astronauts limit water use to only about three US gallons (11 L) per day.[120]

Insignia

[edit]

In Russia, cosmonauts are awarded Pilot-Cosmonaut of the Russian Federation upon completion of their missions, often accompanied with the award of Hero of the Russian Federation. This follows the practice established in the USSR where cosmonauts were usually awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union.

At NASA, those who complete astronaut candidate training receive a silver lapel pin. Once they have flown in space, they receive a gold pin. U.S. astronauts who also have active-duty military status receive a special qualification badge, known as the Astronaut Badge, after participation on a spaceflight. The United States Air Force also presents an Astronaut Badge to its pilots who exceed 50 miles (80 km) in altitude.

Deaths

[edit]

As of 2020[update], eighteen astronauts (fourteen men and four women) have died during four space flights. By nationality, thirteen were American, four were Russian (Soviet Union), and one was Israeli.

As of 2020[update], eleven people (all men) have died training for spaceflight: eight Americans and three Russians. Six of these were in crashes of training jet aircraft, one drowned during water recovery training, and four were due to fires in pure oxygen environments.

Astronaut David Scott left a memorial consisting of a statuette titled Fallen Astronaut on the surface of the Moon during his 1971 Apollo 15 mission, along with a list of the names of eight of the astronauts and six cosmonauts known at the time to have died in service.[121]

The Space Mirror Memorial, which stands on the grounds of the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, is maintained by the Astronauts Memorial Foundation and commemorates the lives of the men and women who have died during spaceflight and during training in the space programs of the United States. In addition to twenty NASA career astronauts, the memorial includes the names of an X-15 test pilot, a U.S. Air Force officer who died while training for a then-classified military space program, and a civilian spaceflight participant.

See also

[edit]- Airman

- Aquanaut

- Cosmonautics Day

- List of astronauts by name

- List of astronauts by year of selection

- List of cosmonauts

- List of human spaceflights

- List of people who have walked on the Moon

- List of space travelers by name

- List of space travelers by nationality

- List of spaceflight records

- Lists of fictional astronauts

- Lists of spacewalks and moonwalks

- Mercury 13 – 13 inactive women astronauts

- Shirley Thomas – author, Men of Space (1960–1968)

- Space suit

- U.S. space exploration history on U.S. stamps

- United States Astronaut Hall of Fame

- Women in space

- Yuri's Night

Explanatory notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b NASA (2006). "Astronaut Fact Book" (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ MacKay, Marie (2005). "Former astronaut visits USU". The Utah Statesman. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "astronaut - Dictionary Definition: Vocabulary.com". vocabulary.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "SpaceX's Crew-3 Launched the 600th Person to Space in 60 Years". 11 November 2021. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "FAI Sporting Code, Section 8, Paragraph 2.18.1" (PDF). 22 May 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Whelan, Mary (5 June 2013). "X-15 Space Pioneers Now Honored as Astronauts". Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Astronaut/Cosmonaut Statistics". www.worldspaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ NASA. "NASA's First 100 Human Space Flights". NASA. Archived from the original on 27 August 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ a b c Encyclopedia Astronautica (2007). "Astronaut Statistics – as of 14 November 2008". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ NASA (2004). "Walking in the Void". NASA. Archived from the original on 6 January 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Kekatos, Mary; Sunseri, Gina (5 June 2024). "Russian cosmonaut becomes 1st person to spend 1,000 cumulative days in space". abc News. Archived from the original on 8 August 2024. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ NASA. "Peggy A. Whitson (PhD)". Biographical Data. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ Paul Dickson (2009). A Dictionary of the Space Age. JHU Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8018-9504-3.

- ^ Dethloff, Henry C. (1993). "Chapter 2: The Commitment to Space". Suddenly Tomorrow Came... A History of the Johnson Space Center. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-1-5027-5358-8. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ a b Brzezinski, Matthew (2007). Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivalries That Ignited the Space Age. New York: Henry Holt & Co. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8050-8147-3.

- ^ a b Gruntman, Mike (2004). Blazing the Trail: The Early History of Spacecraft and Rocketry. Reston, VA: AIAA. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-56347-705-8.

- ^ "TheSpaceRace.com – Glossary of Space Exploration Terminology". Archived from the original on 5 January 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ Ingham, John L.: Into Your Tent, Plantech (2010): page 82.

- ^ IAF (16 August 2010). "IAF History". International Astronautical Federation. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ a b Dismukes, Kim – NASA Biography Page Curator (15 December 2005). "Astronaut Biographies". Johnson Space Center, NASA. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- ^ ESA (10 April 2008). "The European Astronaut Corps". ESA. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ Kotlyakov, Vladimir; Komarova, Anna (2006). Elsevier's Dictionary of Geography: in English, Russian, French, Spanish and German. Elsevier. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-08-048878-3.

- ^ Katarzyna Kłosińska, University of Warsaw (16 December 2016). "Astronauta a kosmonauta". PWN. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Hall, Rex D.; David, Shayler; Vis, Bert (5 October 2007). Russia's Cosmonauts: Inside the Yuri Gagarin Training Center. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-73975-5.

- ^ Knapton, Sarah (17 September 2015). "Russia forgot to send toothbrush with first woman in space". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ McDonald, Sue (December 1998). Mir Mission Chronicle: November 1994 – August 1996 (PDF). NASA. pp. 52–53. NASA/TP-98-207890. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ "Illustrious alumnus: Former astronaut Thagard recounts thrills of spaceflight". www.utsouthwestern.edu. Utsouthwestern.edu. 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Astronaut-Physician Counting Down to Blastoff Aboard Russian Craft: Shuttle: Dr. Norman Thagard will become the first American to leave the Earth aboard a Soyuz rocket. Mission will take them to the Mir space station". Los Angeles Times. 22 January 1995. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Ян Ливэй – первый китайский космонавт, совершивший первый в Китае пилотируемый космический полет" [Yang Liwei, the first Chinese astronaut who has made China's first manned space flight]. fmprc.gov.cn (in Russian). 13 October 2005. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "Chinese embassy in Russia press-release". ru.china-embassy.org (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "The Axiom-1 crew launches today—are these guys tourists, astronauts, or what? – Ars Technica OpenForum". arstechnica.com. 8 April 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "太空人 : astronaut...: tài kōng rén | Definition | Mandarin Chinese Pinyin English Dictionary | Yabla Chinese". chinese.yabla.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ "Chinese taikonaut dismisses environment worries about new space launch center". China View. 26 January 2008. Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ ""Taikonauts" a sign of China's growing global influence". China View. 25 September 2008. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ Xinhua (2008). "Chinese taikonaut debuts spacewalk". People's Daily Online. Archived from the original on 30 September 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Chiew, Lee Yih (19 May 1998). "Google search of "taikonaut" sort by date". Usenet posting. Chiew Lee Yih. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Chiew, Lee Yih (10 March 1996). "Chiew Lee Yih misspelled "taikonaut" 2 years before it first appear". Usenet posting. Chiew Lee Yih. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Ananthaswamy, Anil (5 January 2010). "Wanted: four 'vyomanauts' for Indian spaceflight". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Mukunth, Vasudevan (23 August 2018). "Infinite in All Directions: A Science Workshop and Why Vyomanaut Is Not Cool". The Wire. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ MTV Uutiset (1 November 2009). ""Sisunautti" haaveilee uudesta Suomen-matkasta". MTV3. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ "Parastronaut feasibility project". ESA. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Parsonson, Andrew (16 February 2021). "'Parastronaut' sought as ESA recruits its first new astronauts in more than a decade". SpaceNews. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (23 November 2022). "Disabled man joins European Space Agency's astronaut programme". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Devlin, Hannah (14 February 2025). "British Paralympian is first person with physical disability cleared for space mission". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2025.

- ^ "Commercial Astronaut Wings Program". United States Department of Transportation. Office of Commercial Space Transportation. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Elburn, Darcy (29 May 2019). "Private Astronaut Missions". nasa.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ "FAA Order 8800.2" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Rivera, Josh (25 July 2021). "Sorry, Jeff Bezos, you're still not an astronaut, according to the FAA". USA Today. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ NASA (2006). "Sally K. Ride, PhD Biography". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "Educator Features: Going Out for a Walk". NASA. Archived from the original on 5 December 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Encyclopedia Astronautica (2007). "Vladimir Remek Czech Pilot Cosmonaut". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Encyclopedia Astronautica (2007). "Salyut 6 EP-7". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ NASA (1985). "Taylor G. Wang Biography". NASA. Archived from the original on 19 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Encyclopedia Astronautica (2007). "Taylor Wang". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 27 August 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ media, Government of Canada, Canadian Space Agency, Directions of communications, Information services and new (4 September 2014). "Space Missions". Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Encyclopedia Astronautica (2007). "Tamayo-Mendez". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Encyclopedia Astronautica (2007). "Baudry". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ NASA (2006). "Sultan Bin Salman Al-Saud Biography". NASA. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ NASA (1985). "Rodolfo Neri Vela (PhD) Biography". NASA. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ BBC News (18 May 1991). "1991: Sharman becomes first Briton in space". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ africaninspace.com (2002). "First African in Space". HBD. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "Blue Origin's Bezos reaches space on 1st passenger flight". Arkansas Online. 20 July 2021. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ BBC News (6 August 2007). "1961: Russian cosmonaut spends day in space". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Robyn Dixon (22 September 2000). "Obituaries—Gherman S. Titov; Cosmonaut Was Second Man to Orbit Earth". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 30 November 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ "William Shatner oldest astronaut at 90 – Here's how space tourism could affect older people". Space.com. 19 October 2021. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "John Herschel Glenn, Jr. (Colonel, USMC, Ret.) NASA Astronaut". NASA. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "Valentina Vladimirovna TERESHKOVA". Archived from the original on 23 April 2011.

- ^ "Puzzle: Civilians in Space (Fourmilog: None Dare Call It Reason)". www.fourmilab.ch. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ "Higher & Faster: Memorial Fund Established for X-15 pilot Joseph A. Walker". Space.com. 27 November 2006. Archived from the original on 13 July 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ NASA (2002). "Byron K. Lichtenberg Biography". NASA. Archived from the original on 19 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (2007). "Paying for a Ride". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ a b BBC News (1990). "Mir Space Station 1986–2001". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Spacefacts (1990). "Akiyama". Spacefacts. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Leonard David (2004). "Pilot Announced on Eve of Private Space Mission". Space.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Royce Carlton Inc (2007). "Michael Melvill, First Civilian Astronaut, SpaceShipOne". Royce Carlton Inc. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (21 September 2021). "What a Fungus Reveals About the Space Program". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ a b NASA (2006). "Astronaut Candidate Training". NASA. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ a b NASA (1995). "Selection and Training of Astronauts". NASA. Archived from the original on 15 February 1997. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Nolen, Stephanie (2002). Promised The Moon: The Untold Story of the First Women in the Space Race. Toronto: Penguin Canada. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-14-301347-1.

- ^ "NASA – Astronauts in Training". www.nasa.gov. Denise Miller: MSFC. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ NASA (2007). "NASA Opens Applications for New Astronaut Class". NASA. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ NASA (2004). "'Next Generation of Explorers' Named". NASA. Archived from the original on 26 November 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ NASA (2004). "NASA's New Astronauts Meet The Press". NASA. Archived from the original on 6 January 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ NASA (2007). "Barbara Radding Morgan – NASA Astronaut biography". NASA. Archived from the original on 2 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Tariq Malik (2007). "NASA Assures That Teachers Will Fly in Space". Space.com. Archived from the original on 25 November 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ NASA (2005). "Educator Astronaut Program". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (27 January 2014). "Beings Not Made for Space". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ Mann, Adam (23 July 2012). "Blindness, Bone Loss, and Space Farts: Astronaut Medical Oddities". Wired. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ Mader, T. H.; et al. (2011). "Optic Disc Edema, Globe Flattening, Choroidal Folds, and Hyperopic Shifts Observed in Astronauts after Long-duration Space Flight". Ophthalmology. 118 (10): 2058–2069. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.021. PMID 21849212. S2CID 13965518. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013.

- ^ Puiu, Tibi (9 November 2011). "Astronauts' vision severely affected during long space missions". zmescience.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Male Astronauts Return With Eye Problems (video)". CNN News. 9 February 2012. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Space Staff (13 March 2012). "Spaceflight Bad for Astronauts' Vision, Study Suggests". Space.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ Kramer, Larry A.; et al. (13 March 2012). "Orbital and Intracranial Effects of Microgravity: Findings at 3-T MR Imaging". Radiology. 263 (3): 819–827. doi:10.1148/radiol.12111986. PMID 22416248. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ "Soviet cosmonauts burnt their eyes in space for USSR's glory". Pravda.Ru. 17 December 2008. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Fong, Kevin (12 February 2014). "The Strange, Deadly Effects Mars Would Have on Your Body". Wired. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (3 November 2017). "Brain Changes in Space Could Be Linked to Vision Problems in Astronauts". Seeker. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "NASA – Advanced Diagnostic Ultrasound in Microgravity". Archived from the original on 29 October 2009.

- ^ Rao, S.; van Holsbeeck, L.; Musial, J. L.; Parker, A.; Bouffard, J. A.; Bridge, P.; Jackson, M.; Dulchavsky, S. A. (2008). "A Pilot Study of Comprehensive Ultrasound Education at the Wayne State University School of Medicine". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 27 (5): 745–749. doi:10.7863/jum.2008.27.5.745. PMID 18424650.

- ^ Evaluation of Shoulder Integrity in Space: First Report of Musculoskeletal US on the International Space Station: http://radiology.rsna.org/content/234/2/319.abstract Archived 20 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Caspermeyer, Joe (23 September 2007). "Space flight shown to alter ability of bacteria to cause disease". Arizona State University. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Dvorsky, George (13 September 2017). "Alarming Study Indicates Why Certain Bacteria Are More Resistant to Drugs in Space". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Dose, K.; Bieger-Dose, A.; Dillmann, R.; Gill, M.; Kerz, O.; Klein, A.; Meinert, H.; Nawroth, T.; Risi, S.; Stridde, C. (1995). "ERA-experiment "space biochemistry"" (PDF). Advances in Space Research. 16 (8): 119–129. Bibcode:1995AdSpR..16h.119D. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(95)00280-R. PMID 11542696. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Horneck G.; Eschweiler, U.; Reitz, G.; Wehner, J.; Willimek, R.; Strauch, K. (1995). "Biological responses to space: results of the experiment "Exobiological Unit" of ERA on EURECA I". Adv. Space Res. 16 (8): 105–18. Bibcode:1995AdSpR..16h.105H. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(95)00279-N. PMID 11542695.

- ^ Cherry, Jonathan D.; Frost, Jeffrey L.; Lemere, Cynthia A.; Williams, Jacqueline P.; Olschowka, John A.; O'Banion, M. Kerry; Liu, Bin (2012). Feinstein, Douglas L (ed.). "Galactic Cosmic Radiation Leads to Cognitive Impairment and Increased Aβ Plaque Accumulation in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease". PLoS ONE. 7 (12) e53275. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...753275C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053275. PMC 3534034. PMID 23300905.

- ^ Staff (1 January 2013). "Study Shows that Space Travel is Harmful to the Brain and Could Accelerate Onset of Alzheimer's". SpaceRef. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (3 January 2013). "Important Research Results NASA Is Not Talking About (Update)". NASA Watch. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (29 October 2015). "Report: NASA needs better handle on health hazards for Mars". AP News. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Staff (29 October 2015). "NASA's Efforts to Manage Health and Human Performance Risks for Space Exploration (IG-16-003)" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ "Astronaut Vision Changes Offer Opportunity for More Research". NASA. 9 February 2012. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Donna R.; et al. (2 November 2017). "Effects of Spaceflight on Astronaut Brain Structure as Indicated on MRI". New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (18): 1746–1753. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1705129. PMID 29091569. S2CID 205102116.

- ^ Foley, Katherine Ellen (3 November 2017). "Astronauts who take long trips to space return with brains that have floated to the top of their skulls". Quartz. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ YOUNG, LAURENCE R. (1 May 1999). "Artificial Gravity Considerations for a Mars Exploration Mission". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 871 (1 OTOLITH FUNCT): 367–378. Bibcode:1999NYASA.871..367Y. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09198.x. ISSN 1749-6632. PMID 10372085. S2CID 32639019.

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (2 October 2018). "Travelling to Mars and deep into space could kill astronauts by destroying their guts, finds Nasa-funded study – Previous work has shown that astronauts could age prematurely and have damaged brain tissue after long journeys". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ BioMed Central (22 November 2018). "ISS microbes should be monitored to avoid threat to astronaut health". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ Singh, Nitin K.; et al. (23 November 2018). "Multi-drug resistant Enterobacter bugandensis species isolated from the International Space Station and comparative genomic analyses with human pathogenic strains". BMC Microbiology. 18 (1) 175. Bibcode:2018BMCMb..18..175S. doi:10.1186/s12866-018-1325-2. PMC 6251167. PMID 30466389.

- ^ "Radiation can impact astronauts' memory temporarily: Here's all you need to know | Health Tips and News". www.timesnownews.com. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ Aria Bendix (4 September 2020). "Space travel can lead to new motor skills but impaired vision, according to a new study of cosmonaut brains". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Jillings, Steven; Van Ombergen, Angelique; Tomilovskaya, Elena; Rumshiskaya, Alena; Litvinova, Liudmila; Nosikova, Inna; Pechenkova, Ekaterina; Rukavishnikov, Ilya; Kozlovskaya, Inessa B.; Manko, Olga; Danilichev, Sergey; Sunaert, Stefan; Parizel, Paul M.; Sinitsyn, Valentin; Petrovichev, Victor; Laureys, Steven; Zu Eulenburg, Peter; Sijbers, Jan; Wuyts, Floris L.; Jeurissen, Ben (4 September 2020). "Macro- and microstructural changes in cosmonauts' brains after long-duration spaceflight". Science Advances. 6 (36) eaaz9488. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.9488J. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz9488. PMC 7473746. PMID 32917625.

- ^ Nevills, Amiko. "NASA – Food in Space Gallery". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ "Human Needs: Sustaining Life During Exploration". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ "Sculpture, Fallen Astronaut". airandspace.si.edu. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

External links

[edit]- "The Human Body in Space". NASA. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- NASA: How to become an astronaut 101 Archived 18 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- List of International partnership organizations Archived 26 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Encyclopedia Astronautica: Phantom cosmonauts

- collectSPACE: Astronaut appearances calendar

- spacefacts Spacefacts.de

- Manned astronautics: facts and figures

- Astronaut Candidate Brochure online Archived 22 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

Astronaut

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Core Definition

An astronaut is a person trained and selected by a human spaceflight program to serve as a commander, pilot, or crew member aboard a spacecraft, enabling the operation and execution of space missions.[2] The term originates from the Greek words astron (star) and nautes (sailor), literally meaning "star sailor," and applies to individuals launched into space as part of professional crews.[2] This role encompasses responsibilities such as vehicle control, scientific experimentation, and mission coordination during orbital or deep-space flights.[2] Professional astronauts are distinguished from spaceflight participants, such as space tourists, who are non-crew individuals carried aboard launch or reentry vehicles without undergoing the rigorous training or operational duties required of certified crew members.[11] Under U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations, spaceflight participants do not qualify as astronauts or crew, as they lack the designation and preparation for active mission roles.[11] This separation ensures that only trained professionals handle critical spacecraft functions, while participants engage in passive travel.[12] Internationally, the role of astronauts is enshrined in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which designates them as "envoys of mankind" in outer space, obligating signatory states to provide all possible assistance in cases of accident, distress, or emergency landing.[13] Article V of the treaty further requires the safe and prompt return of astronauts to the state of registry of their spacecraft and mandates mutual aid among astronauts from different nations during space activities.[13] This framework underscores the cooperative and humanitarian aspects of human spaceflight, transcending national boundaries.[13] The astronaut role has evolved from its origins in military test pilots, who dominated early selections for their expertise in high-risk vehicle handling, to a broader cadre of specialists including scientists, engineers, physicians, and international partners to support complex, multidisciplinary missions.[9] NASA's initial 1959 cohort consisted entirely of test pilots, but subsequent groups incorporated mission specialists focused on scientific and technical operations, reflecting the shift toward sustained exploration and international collaboration.[9] Today, astronaut candidates draw from diverse fields to address the demands of programs like Artemis, emphasizing adaptability across piloting, research, and engineering disciplines.[9]International Terms

The term "astronaut" derives from the Greek words astron (star) and nautes (sailor), literally meaning "star sailor," and was coined in scientific speculation as early as 1929 before gaining popularity through science fiction in the mid-20th century.[14] It was formally adopted by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in 1958 as the official designation for individuals trained for spaceflight, and it remains the standard term used by NASA and most Western space agencies, including those in Europe and Canada, to describe professionals who travel beyond Earth's atmosphere.[15] This nomenclature reflects a focus on stellar navigation, aligning with the exploratory ethos of early American space programs. In contrast, the Russian space agency Roscosmos employs the term "cosmonaut," derived from the Greek kosmos (universe) and nautes (sailor), meaning "universe sailor."[16] The word entered usage in 1959, coinciding with the Soviet Union's preparations for manned spaceflight under the Vostok program, and was first applied to Yuri Gagarin during his historic orbital flight in 1961.[17] This term underscores the Soviet emphasis on cosmic exploration and has persisted through Roscosmos's operations, distinguishing Russian spacefarers from their Western counterparts in international discourse. For China's space program, managed by the China National Space Administration (CNSA), the official term is yuhangyuan (宇航员), which translates from Mandarin as "space navigator" or "universe traveler," reflecting a direct linguistic focus on navigation through the cosmos.[18] An English-language neologism, "taikonaut," emerged in 1998 from the Mandarin taikong (space) combined with the Greek -naut (sailor), and gained traction in Western media following China's first manned mission in 2003 with the Shenzhou program.[19] While taikonaut is not officially endorsed by CNSA, it has become a common informal descriptor for Chinese space personnel, paralleling the cultural adaptations seen in other programs. The European Space Agency (ESA) occasionally uses "spationaut" (or spationaute in French), derived from the Latin spatium (space) and Greek nautes (sailor), meaning "space sailor," particularly in French-speaking contexts to denote European astronauts.[20] This term entered limited usage in the 1990s as ESA expanded its astronaut corps, though "astronaut" predominates in official English communications. Similarly, Malaysia's Angkasawan program, launched in 2007 to send its first national to the International Space Station, adopted angkasawan from Malay, directly meaning "astronaut" or "space traveler," to culturally localize the role within its national space initiatives.[22] These variations highlight how spacefaring nations adapt terminology to blend indigenous languages with classical roots, fostering national identity in global space endeavors.Historical Development

Early Spaceflight Milestones

The era of early human spaceflight began with the Soviet Union's Vostok 1 mission on April 12, 1961, when cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to reach space, completing a single orbit of Earth in a 108-minute flight aboard the Vostok spacecraft.[23][24] This pioneering achievement demonstrated that humans could survive the rigors of launch, weightlessness, and reentry, paving the way for subsequent orbital missions.[25] In response, the United States accelerated its Project Mercury, initiated in 1958 and spanning until 1963, to achieve manned suborbital and orbital flights using one-person capsules launched by Redstone and Atlas rockets.[26] The program's first success came on May 5, 1961, with astronaut Alan Shepard's suborbital flight aboard Freedom 7, lasting 15 minutes and reaching an altitude of about 187 kilometers, marking the initial American step into space.[27] Building on this, John Glenn became the first American to orbit Earth on February 20, 1962, during the Friendship 7 mission, completing three circuits in under five hours and confirming the viability of human-piloted orbital operations.[26] The Soviet program advanced gender diversity in space with cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova's Vostok 6 flight on June 16, 1963, where she became the first woman in space, orbiting Earth 48 times over nearly 71 hours and conducting observations that contributed to biomedical data on female physiology in microgravity.[28] The culmination of early lunar ambitions arrived with NASA's Apollo program, which achieved the first human Moon landing on July 20, 1969, during Apollo 11, as astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin descended in the Lunar Module Eagle to the Sea of Tranquility, with Armstrong uttering the iconic words upon his first step: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."[29][4] Over the subsequent years, six Apollo missions (11 through 17, excluding the aborted Apollo 13) successfully landed on the Moon between 1969 and 1972, enabling a total of 12 astronauts—six pairs from those crews—to conduct extravehicular activities, collect 382 kilograms of lunar samples, and perform scientific experiments that expanded knowledge of the Moon's geology and environment.[30] The Soviet Union advanced orbital station technology with the Salyut program, launching Salyut 1 in 1971 as the world's first space station, hosting crews for up to 23 days despite the tragic loss of the Soyuz 11 crew in 1971. A landmark in international cooperation was the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in July 1975, where American astronauts Thomas Stafford, Vance Brand, and Deke Slayton docked with the Soviet Soyuz 19 spacecraft crewed by Alexei Leonov and Valery Kubasov, marking the first joint U.S.-Soviet space mission and symbolizing détente during the Cold War.[31] Transitioning from lunar exploration to sustained orbital presence, the United States launched Skylab in May 1973 as its first space station, repurposed from a Saturn V upper stage and serving as an orbital laboratory until 1974.[32] Three crews of three astronauts each visited Skylab across missions lasting 28, 59, and 84 days, respectively, conducting over 270 experiments in fields such as solar physics, Earth resources, and human adaptation to long-duration spaceflight, while demonstrating repairs to the station's damaged solar arrays and micrometeoroid shield during the initial crew's arrival.[33]Modern Achievements and Records

The Space Shuttle program, operational from 1981 to 2011, marked a significant era in reusable spacecraft technology, conducting 135 missions that carried a total of 355 individuals into orbit.[34] These flights facilitated the deployment of satellites, conducted scientific experiments, and supported the construction of the International Space Station, with notable milestones including the first flight of an American woman, Sally Ride, aboard STS-7 in 1983. Another highlight was the planned inclusion of Christa McAuliffe as the first teacher in space on STS-51-L in 1986, though the mission ended tragically in the Challenger disaster.[35] The International Space Station (ISS), continuously inhabited since 2000 following its assembly beginning in 1998, has hosted 290 visitors from 26 countries as of November 2025, fostering unprecedented international collaboration in microgravity research.[8] This era has seen records for long-duration stays, including Russian cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov's 437-day mission on the predecessor Mir station from 1994 to 1995, which remains the longest single human spaceflight to date and informed ISS operations.[36] Private sector advancements have democratized access to space since the 2010s, with SpaceX's Crew Dragon achieving its first operational crewed flight in May 2020 under NASA's Commercial Crew Program, enabling routine astronaut transport to the ISS. Suborbital tourism emerged through Virgin Galactic's VSS Unity flights, starting with commercial passenger missions in 2023, and Blue Origin's New Shepard, which conducted its inaugural crewed suborbital flight in July 2021.[37] A pivotal orbital milestone was the Inspiration4 mission in September 2021, the first all-civilian crewed flight to reach orbit aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon, raising funds for pediatric research while demonstrating private capabilities for extended missions. Diversity in astronaut selection has expanded notably in modern spaceflight, with Guion Bluford becoming the first African American in space on STS-8 in 1983. Age records include John Glenn's return to space at 77 years old on STS-95 in 1998, the oldest person to fly at that time, and Wally Funk's suborbital flight at 82 aboard Blue Origin's New Shepard in 2021, setting the record for the oldest woman in space. Regarding LGBTQ+ representation, Sally Ride was posthumously identified in 2012 as the first known LGBTQ+ astronaut, having flown in 1983, though public acknowledgment during active careers has grown in the 2020s.[38] In terms of distance, the Apollo 13 mission in 1970 achieved the farthest human venture from Earth at approximately 400,000 km, a record contextualized in modern efforts to push boundaries further.[39] The ongoing Artemis program aims to return humans to the lunar surface, with Artemis III targeted for a landing in 2027, building toward sustainable presence on the Moon and preparation for Mars.[40]Selection and Preparation

Candidacy Criteria

Candidacy criteria for astronauts vary by space agency but generally emphasize citizenship, advanced education in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) fields, relevant professional experience, and rigorous physical and medical fitness to ensure safe performance in space environments.[6][41] These requirements have evolved since the earliest selections, such as NASA's 1959 group of military test pilots, to include more diverse professional backgrounds while maintaining high standards for mission success. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) requires candidates to be U.S. citizens with a master's degree in a STEM field from an accredited institution, or equivalent qualifications such as two years toward a doctoral program, a medical degree, or completion of a test pilot school program.[6] Applicants must also demonstrate at least three years of related professional experience following the degree or accumulate 1,000 hours of pilot-in-command time in jet aircraft, with medical residents counting residency toward experience.[6] Physically, candidates must pass NASA's long-duration flight astronaut physical, including distant and near visual acuity correctable to 20/20 in each eye and blood pressure not exceeding 140/90 in a sitting position.[42] Russia's Roscosmos State Corporation for Space Activities sets similar educational and experiential thresholds for cosmonauts, requiring Russian citizenship, a higher education degree in engineering, sciences, aviation, or related fields, and relevant professional experience in the specialty.[43] Candidates must be no older than 35 years at application and undergo comprehensive medical evaluations emphasizing physical fitness, with a focus on engineering proficiency to support spacecraft operations.[44][43] The European Space Agency (ESA) mandates citizenship of an ESA member or associated state, along with a minimum master's degree in natural sciences, medicine, engineering, mathematics, or computer sciences, followed by at least three years of professional experience such as research or clinical work.[41] Fluency in English and knowledge of another language are essential for international collaboration, with physical fitness demonstrated via a medical certificate equivalent to a private pilot license or higher; the maximum age at application is 50.[41] China's National Space Administration (CNSA) prioritizes advanced degrees, preferably a master's or PhD in engineering or related STEM disciplines, drawing from diverse backgrounds including scientists, physicians, and engineers to support missions like the Tiangong space station.[45][46] Multilingual capabilities, particularly in English, aid potential international engagements, though selections often favor military pilots with technical expertise.[45] Private space programs, such as those operated by SpaceX, apply less rigid criteria compared to government agencies, prioritizing technical skills, adaptability, and problem-solving over formal astronaut training.[47] For missions like Inspiration4 or Axiom Space flights, selections have included civilians from business, science, and engineering fields, with opportunities for self-funded participation to broaden access beyond traditional prerequisites.[47] Selection processes are highly competitive, with NASA typically choosing 10–12 candidates every few years from over 8,000–12,000 applicants; for instance, the 2021 class selected 12 from 12,000, while the 2025 class chose 10 from more than 8,000.[48] Recent selections reflect a shift toward greater inclusivity, exemplified by NASA's 2025 astronaut candidate class, where women outnumbered men for the first time (six women and four men), aligning with broader efforts to diversify the corps.[48][49]Training Regimens

Astronaut training regimens typically commence immediately following selection as candidates, marking the beginning of an intensive multi-year preparation process designed to equip individuals with the technical, operational, and survival skills necessary for spaceflight. At agencies such as NASA, basic training lasts approximately two years and is conducted primarily at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, where candidates learn core competencies including spacecraft systems operations, robotics handling, and extravehicular activities (EVAs), also known as spacewalks.[6] This phase emphasizes hands-on instruction in the intricacies of vehicle controls, life support systems, and robotic manipulators like the Canadarm2 used on the International Space Station (ISS), ensuring astronauts can perform complex tasks in isolated environments.[50] Training incorporates simulations of mission scenarios to build proficiency in EVA procedures, where candidates practice donning spacesuits and maneuvering in simulated microgravity to repair or assemble orbital structures.[51] Specialized simulations form a critical component of astronaut preparation, replicating the physical and environmental challenges of spaceflight to enhance safety and performance. The Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory at Johnson Space Center, a 6.2-million-gallon pool, allows astronauts to train for zero-gravity conditions during EVAs by suspending full-scale mockups of spacecraft and station components underwater, providing realistic practice for tasks lasting up to eight hours.[52] Centrifuge facilities simulate the high G-forces encountered during launch and reentry, with astronauts experiencing up to 8 Gs to acclimate to acceleration stresses and maintain cognitive function under duress, a practice reinstated for NASA crews in recent years.[53] Additionally, wilderness survival training, conducted over three days in remote areas like forests in Maine or deserts in Nevada, teaches candidates essential skills such as building shelters, sourcing water, and signaling for rescue in the event of an off-nominal landing.[54] For multinational missions like those to the ISS, cross-training at Johnson Space Center accommodates partners from agencies including Roscosmos, ESA, JAXA, and CSA, fostering interoperability through shared simulations and joint exercises. Astronauts undergo language instruction at the Johnson Space Center's Language Education Center, where NASA personnel achieve conversational proficiency in Russian—essential for Soyuz operations—while international counterparts learn English, supplemented by cultural modules to address communication nuances and team dynamics in diverse crews.[55] This collaborative approach ensures seamless coordination during long-duration flights, with training emphasizing conflict resolution and shared protocols. In contrast, preparation for private astronauts, particularly through companies like Axiom Space, is more condensed, often spanning several months and totaling 700 to 1,000 hours focused on safety protocols, basic vehicle operations, and emergency response rather than exhaustive technical depth. For suborbital flights, such as those offered by commercial providers, training emphasizes passenger safety briefings and physiological adaptation over extended simulations, aligning with shorter mission profiles. By 2025, these programs have evolved to incorporate updates for emerging commercial orbital flights, including enhanced integration with SpaceX Crew Dragon systems for missions like Axiom's Ax-4.[56] Mission-specific tailoring further refines regimens to align with unique objectives, such as geological field training for lunar explorations under NASA's Artemis program. Astronauts participate in analog missions in volcanic regions like Arizona's San Francisco Volcanic Field or Norway's lunar-like terrains, learning to identify regolith samples, map craters, and document surface features to support scientific return during landings targeted for the late 2020s.[57] This hands-on geology instruction, ramped up since 2023, equips crews to maximize sample collection efficiency while navigating extraterrestrial hazards.Operational Roles

Mission Duties

Astronauts undertake a range of critical responsibilities during space missions, encompassing vehicle operations, scientific research, and extravehicular activities to ensure mission success from launch through landing.[2] These duties are divided among crew roles such as commander, pilot, and mission specialists, with the commander holding overall authority for crew safety, vehicle management, and mission objectives.[58][59] In the pre-launch phase, astronauts perform final systems checks, including leak verifications on the spacecraft and suits, while reviewing emergency procedures and checklists to confirm readiness for ascent.[60] During in-flight operations, pilots and commanders operate spacecraft controls for navigation, orbital maneuvers, and rendezvous with targets like the International Space Station (ISS), where they monitor automated docking or intervene manually if required.[61] Emergency procedures involve rapid response protocols, such as abort sequences or contingency maneuvers, to mitigate risks like system failures.[62] Reentry duties include executing de-orbit burns, monitoring descent trajectories, and piloting the vehicle through atmospheric interface for a safe landing.[63] Science officers and mission specialists conduct experiments in microgravity, focusing on fields like fluid physics—where phenomena such as capillary action behave differently without gravity—and biology, including studies on plant growth or protein crystallization to advance materials science and medicine.[64][65] They also handle payload deployment, such as releasing small satellites from the ISS via systems like the Kaber deployer or NanoRacks, enabling orbit insertion for Earth observation or technology demonstrations.[66] Extravehicular activity (EVA), or spacewalks, forms a core duty for maintenance and repairs outside the spacecraft, with astronauts donning suits capable of supporting 6 to 8 hours of activity in the vacuum of space.[67] As of November 2025, the ISS has hosted 277 such EVAs since 1998, totaling over 1,800 hours, primarily for tasks like installing solar arrays, replacing power regulators, and upgrading communication systems.[68] For emerging missions, astronauts adapt duties to new environments; in NASA's Artemis program, crew members will pilot the Human Landing System to descend to and ascend from the lunar surface, conducting surface operations during approximately 6.5-day stays on the Moon as part of a ~30-day mission.[69] In Mars analog simulations like the Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog (CHAPEA), participants perform operational tasks such as simulated surface walks, vegetable cultivation in controlled habitats, and robotic arm operations to mimic planetary exploration.[70] These roles build on rigorous training to prepare for extended deep-space operations.[6]Ground and Support Functions