Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rhyniophyte

View on Wikipedia

| Rhyniophyte Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

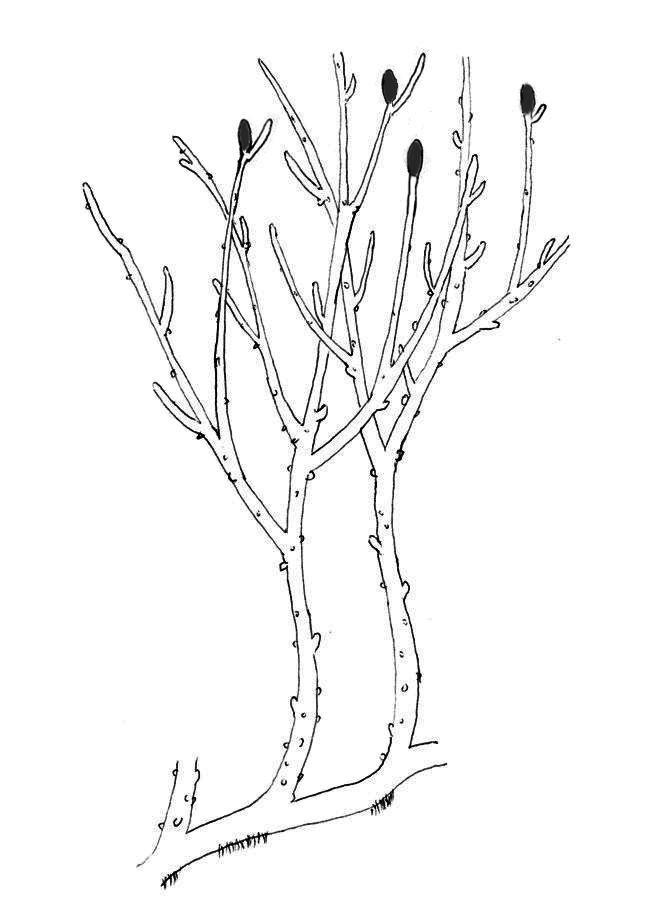

| Reconstruction of Rhynia gwynne-vaughanii[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Polysporangiophytes |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Stem group: | †Rhyniophytes |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The rhyniophytes are a group of extinct early vascular plants that are considered to be similar to the genus Rhynia, found in the Early Devonian (around 420 to 393 million years ago). Sources vary in the name and rank used for this group, some treating it as the class Rhyniopsida, others as the subdivision Rhyniophytina or the division Rhyniophyta. The first definition of the group, under the name Rhyniophytina, was by Banks,[2]: 8 since when there have been many redefinitions,[1]: 96–97 including by Banks himself. "As a result, the Rhyniophytina have slowly dissolved into a heterogeneous collection of plants ... the group contains only one species on which all authors agree: the type species Rhynia gwynne-vaughanii".[1]: 94 When defined very broadly, the group consists of plants with dichotomously branched, naked aerial axes ("stems") with terminal spore-bearing structures (sporangia).[3]: 227 The rhyniophytes are considered to be stem group tracheophytes (vascular plants).

Definitions

[edit]The group was described as a subdivision of the division Tracheophyta by Harlan Parker Banks in 1968 under the name Rhyniophytina. The original definition was: "plants with naked (lacking emergences), dichotomizing axes bearing sporangia that are terminal, usually fusiform and may dehisce longitudinally; they are diminutive plants and, in so far as is known, have a small terete xylem strand with a central protoxylem."[2]: 8 [4] With this definition, they are polysporangiophytes, since their sporophytes consisted of branched stems bearing sporangia (spore-forming organs). They lacked leaves or true roots but did have simple vascular tissue. Informally, they are often called rhyniophytes or, as mentioned below, rhyniophytoids.

However, as originally circumscribed, the group was found not to be monophyletic since some of its members are now known to lack vascular tissue. The definition that seems to be used most often now is that of D. Edwards and D.S. Edwards: "plants with smooth axes, lacking well-defined spines or leaves, showing a variety of branching patterns that may be isotomous, anisotomous, pseudomonopodial or adventitious. Elongate to globose sporangia were terminal on main axes or on lateral systems showing limited branching. It seems probable that the xylem, comprising a solid strand of tracheids, was centrarch."[5]: 216 However, Edwards and Edwards also decided to include rhyniophytoids, plants which "look like rhyniophytes, but cannot be assigned unequivocally to that group because of inadequate anatomical preservation", but exclude plants like Aglaophyton and Horneophyton which definitely do not possess tracheids.[5]: 214–215

In 1966, slightly before Banks created the subdivision, the group was treated as a division under the name Rhyniophyta.[6] Taylor et al. in their book Paleobotany use Rhyniophyta as a formal taxon,[3]: 1028 but with a loose definition: plants "characterized by dichotomously branched, naked aerial axes with terminal sporangia".[3]: 227 They thus include under "other rhyniophytes" plants apparently without vascular tissue.[3]: 246ff

In 2010, the name paratracheophytes was suggested, to distinguish such plants from 'true' tracheophytes or eutracheophytes.[7]

In 2013, Hao and Xue returned to the earlier definition. Their class Rhyniopsida (rhyniopsids) is defined by the presence of sporangia that terminate isotomous branching systems (i.e. the plants have branching patterns in which the branches are equally sized, rather than one branch dominating, like the trunk of a tree). The shape and symmetry of the sporangia was then used to divide up the group. Rhynialeans (order Rhyniales), such as Rhynia gwynne-vaughanii, Stockmansella and Huvenia, had radially symmetrical sporangia that were longer than wide and possessed vascular tissue with S-type tracheids. Cooksonioids, such as Cooksonia pertoni, C. paranensis and C. hemisphaerica, had radially symmetrical or trumpet-shaped sporangia, without clear evidence of vascular tissue. Renalioids, such as Aberlemnia, Cooksonia crassiparietilis and Renalia had bilaterally symmetrical sporangia and protosteles.[8]: 329

Taxonomy

[edit]There is no agreement on the formal classification to be used for the rhyniophytes.[1]: 96–97 The following are some of the names which may be used:

Phylogeny

[edit]In 2004, Crane et al. published a cladogram for the polysporangiophytes in which the Rhyniaceae are shown as the sister group of all other tracheophytes (vascular plants).[12] Some other former "rhyniophytes", such as Horneophyton and Aglaophyton, are placed outside the tracheophyte clade, as they did not possess true vascular tissue (in particular did not have tracheids). However, both Horneophyton and Aglaophyton have been tentatively classified as tracheophytes in at least one recent cladistic analysis of Early Devonian land plants.[8]: 244–245

Partial cladogram by Crane et al. including the more certain rhyniophytes:[12]

| polysporangiophytes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

(See the Polysporangiophyte article for the expanded cladogram.)

Genera

[edit]The taxon and informal terms corresponding to it have been used in different ways. Hao and Xue in 2013 circumscribed their Rhyniopsida quite broadly, dividing it into rhynialeans, cooksonioids and renalioids.[8]: 47–49 Genera included by Hao and Xue are listed below, with assignments to their three subgroups where these are given.[8]: 329

- Aberlemnia (renalioids)

- Aglaophyton (rhynialeans)

- Caia

- Cooksonia (cooksonioids + renalioids)

- Culullitheca

- Eogaspesiea (= Eogaspesia) (rhynialeans)

- Eorhynia

- Filiformorama

- Fusitheca (= Fusiformitheca)

- Grisellatheca

- Hsua (=Hsüa) (renalioids)

- Huia

- Huvenia (rhynialeans)

- Junggaria (= Cooksonella, Eocooksonia)

- Pertonella

- Renalia (renalioids)

- Resilitheca

- Rhynia (rhynialeans)

- Salopella (rhynialeans?)

- Sartilmania

- Sennicaulis

- Sporathylacium

- Steganotheca

- Stockmansella (rhynialeans)

- Tarrantia (rhynialeans?)

- Tortilicaulis

- Uskiella (rhynialeans)

It has been suggested that the poorly preserved Eohostimella, found in deposits of Early Silurian age (Llandovery, around 440 to 430 million years ago), may also be a rhyniophyte.[13] Others have placed some of these genera in different groups. For example, Tortilicaulis has been considered to be a horneophyte.[12]

Rhynie flora

[edit]The general term "rhyniophytes" or "rhyniophytoids" is sometimes used for the assemblage of plants found in the Rhynie chert Lagerstätte - rich fossil beds in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and roughly coeval sites with similar flora. Used in this way, these terms refer to a floristic assemblage of more or less related early land plants, not a taxon. Though the rhyniophytes are well represented, plants with simpler anatomy, like Aglaophyton, are also common; there are also more complex plants, like Asteroxylon, which has a very early form of leaves.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Kenrick, Paul & Crane, Peter R. (1997), The Origin and Early Diversification of Land Plants: A Cladistic Study, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, ISBN 978-1-56098-730-7

- ^ a b c Andrews, H.N.; Kasper, A. & Mencher, E. (1968), "Psilophyton forbesii, a New Devonian Plant from Northern Maine", Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 95 (1): 1–11, doi:10.2307/2483801, JSTOR 2483801

- ^ a b c d e Taylor, T.N.; Taylor, E.L. & Krings, M. (2009). Paleobotany, The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants (2nd ed.). Amsterdam; Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-373972-8.

- ^ a b Banks, H.P. (1968), "The early history of land plants", in Drake, E.T. (ed.), Evolution and Environment: A Symposium Presented on the Occasion of the 100th Anniversary of the Foundation of Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, pp. 73–107

- ^ a b Edwards, D.; Edwards, D.S. (1986), "A reconsideration of the Rhyniophytina Banks", in Spicer, R.A.; Thomas, B.A. (eds.), Systematic and taxonomic approaches in palaeobotany, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 199–218

- ^ a b Cronquist, A.; Takhtajan, A. & Zimmermann, W. (1966), "On the higher Taxa of Embryobionta", Taxon, 2 (4): 129–134, doi:10.2307/1217531, JSTOR 1217531

- ^ Gonez, P. & Gerrienne, P. (2010a), "A New Definition and a Lectotypification of the Genus Cooksonia Lang 1937", International Journal of Plant Sciences, 171 (2): 199–215, doi:10.1086/648988

- ^ a b c d Hao, Shougang & Xue, Jinzhuang (2013), The Early Devonian Posongchong Flora of Yunnan – A Contribution to an Understanding of the Evolution and Early Diversification of Vascular Plants, Beijing: Science Press, ISBN 978-7-03-036616-0, retrieved 2019-10-25

- ^ As Rhyniales in: Yakovlev, Nikolai, ed. (1925). Учебник палеонтологии (Uchebnik paleontologii; Textbook of Palaeontology, 3rd edition only). Leningrad-Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe izdateľstvo. pp. 408–409.

- ^ Němejc, F. (1950), "The natural systematic of plants in the light of the present palaeontological documents", Sborník Národního Muzea V Praze: Řada B, Přírodni Vědy, 6 (3): 55

- ^ Kidston, R. & Lang, W.H. (1920), "On Old Red Sandstone plants showing structure, from the Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part II. Additional notes on Rhynia Gwynne-Vaughani, Kidston and Lang; with descriptions of Rhynia major, n.sp., and Hornea Lignieri, n.g., n.sp.", Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 52 (3): 603–627, doi:10.1017/S0080456800004488

- ^ a b c Crane, P.R.; Herendeen, P. & Friis, E.M. (2004), "Fossils and plant phylogeny", American Journal of Botany, 91 (10): 1683–99, doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1683, PMID 21652317

- ^ Niklas, K.J. (1979), "An Assessment of Chemical Features for the Classification of Plant Fossils", Taxon, 28 (5/6): 505–516, doi:10.2307/1219787, JSTOR 1219787

- ^ Kidston, R. & Lang, W.H. (1920), "On Old Red Sandstone plants showing structure, from the Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part III. Asteroxylon mackiei, Kidston and Lang.", Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 52 (3): 643–680, doi:10.1017/S0080456800004506