Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

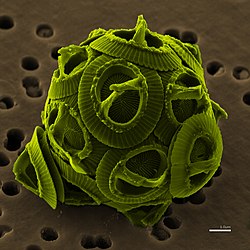

Algae

View on Wikipedia

| Algae | |

|---|---|

| Organisms that perform oxygenic photosynthesis, except land plants | |

Marine algae growing on the sea bed in shallow waters | |

Freshwater microscopic unicellular and colonial algae | |

| Traditional algal divisions[1][2] | |

| Prokaryotic | Cyanobacteria |

| Eukaryotic (primary endosymbiosis) | Glaucophyta, Rhodophyta, Prasinodermophyta, Chlorophyta, Charophyta* |

| Eukaryotic (secondary endosymbiosis) | Chlorarachniophyta, Chromeridophyta, Cryptophyta, Dinoflagellata, Euglenophyta (partially), Haptophyta, Heterokontophyta |

| *paraphyletic, it excludes land plants | |

| Diversity | |

| Living | 50,605 species |

| Fossil | 10,556 species |

Algae (/ˈældʒiː/ ⓘ AL-jee,[3] UK also /ˈælɡiː/ AL-ghee; sg.: alga /ˈælɡə/ ⓘ AL-gə) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthetic organisms that are not land plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular microalgae, such as cyanobacteria,[a] Chlorella, and diatoms, to multicellular macroalgae such as kelp or brown algae which may grow up to 50 metres (160 ft) in length. Most algae are aquatic organisms and lack many of the distinct cell and tissue types, such as stomata, xylem, and phloem that are found in land plants. The largest and most complex marine algae are called seaweeds. In contrast, the most complex freshwater forms are the Charophyta, a division of green algae which includes, for example, Spirogyra and stoneworts. Algae that are carried passively by water are plankton, specifically phytoplankton.

Algae constitute a polyphyletic group[4] because they do not include a common ancestor, and although eukaryotic algae with chlorophyll-bearing plastids seem to have a single origin (from symbiogenesis with cyanobacteria),[5] they were acquired in different ways. Green algae are a prominent example of algae that have primary chloroplasts derived from endosymbiont cyanobacteria. Diatoms and brown algae are examples of algae with secondary chloroplasts derived from endosymbiotic red algae, which they acquired via phagocytosis.[6] Algae exhibit a wide range of reproductive strategies, from simple asexual cell division to complex forms of sexual reproduction via spores.[7]

Algae lack the various structures that characterize plants (which evolved from freshwater green algae), such as the phyllids (leaf-like structures) and rhizoids of bryophytes (non-vascular plants), and the roots, leaves and other xylemic/phloemic organs found in tracheophytes (vascular plants). Most algae are autotrophic, although some are mixotrophic, deriving energy both from photosynthesis and uptake of organic carbon either by osmotrophy, myzotrophy or phagotrophy. Some unicellular species of green algae, many golden algae, euglenids, dinoflagellates, and other algae have become heterotrophs (also called colorless or apochlorotic algae), sometimes parasitic, relying entirely on external energy sources and have limited or no photosynthetic apparatus.[8][9][10] Some other heterotrophic organisms, such as the apicomplexans, are also derived from cells whose ancestors possessed chlorophyllic plastids, but are not traditionally considered as algae. Algae have photosynthetic machinery ultimately derived from cyanobacteria that produce oxygen as a byproduct of splitting water molecules, unlike other organisms that conduct anoxygenic photosynthesis such as purple and green sulfur bacteria. Fossilized filamentous algae from the Vindhya basin have been dated to 1.6 to 1.7 billion years ago.[11]

Because of the wide range of types of algae, there is a correspondingly wide range of industrial and traditional applications in human society. Traditional seaweed farming practices have existed for thousands of years and have strong traditions in East Asian food cultures. More modern algaculture applications extend the food traditions for other applications, including cattle feed, using algae for bioremediation or pollution control, transforming sunlight into algae fuels or other chemicals used in industrial processes, and in medical and scientific applications. A 2020 review found that these applications of algae could play an important role in carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change while providing lucrative value-added products for global economies.[12]

Etymology and study

[edit]The singular alga is the Latin word for 'seaweed' and retains that meaning in English.[13] The etymology is obscure. Although some speculate that it is related to Latin algēre, 'be cold',[14] no reason is known to associate seaweed with temperature. A more likely source is alliga, 'binding, entwining'.[15]

The Ancient Greek word for 'seaweed' was φῦκος (phŷkos), which could mean either the seaweed (probably red algae) or a red dye derived from it. The Latinization, fūcus, meant primarily the cosmetic rouge. The etymology is uncertain, but a strong candidate has long been some word related to the Biblical פוך (pūk), 'paint' (if not that word itself), a cosmetic eye-shadow used by the ancient Egyptians and other inhabitants of the eastern Mediterranean. It could be any color: black, red, green, or blue.[16]

The study of algae is most commonly called phycology (from Greek phykos 'seaweed'); the term algology is falling out of use.[17]

Description

[edit]

The algae are a heterogeneous group of mostly photosynthetic organisms that produce oxygen and lack the reproductive features and structural complexity of land plants. This concept includes the cyanobacteria, which are prokaryotes, and all photosynthetic protists, which are eukaryotes. They contain chlorophyll a as their primary photosynthetic pigment, and generally inhabit aquatic environments.[18][19]

However, there are many exceptions to this definition. Many non-photosynthetic protists are included in the study of algae, such as the heterotrophic relatives of euglenophytes[19] or the numerous species of colorless algae that have lost their chlorophyll during evolution (e.g., Prototheca). Some exceptional species of algae tolerate dry terrestrial habitats, such as soil, rocks, or caves hidden from light sources, although they still need enough moisture to become active.[19]

Morphology

[edit]

A range of algal morphologies is exhibited, and convergence of features in unrelated groups is common. The only groups to exhibit three-dimensional multicellular thalli are the reds and browns, and some chlorophytes.[20] Apical growth is constrained to subsets of these groups: the florideophyte reds, various browns, and the charophytes.[20] The form of charophytes is quite different from those of reds and browns, because they have distinct nodes, separated by internode 'stems'; whorls of branches reminiscent of the horsetails occur at the nodes.[20] Conceptacles are another polyphyletic trait; they appear in the coralline algae and the Hildenbrandiales, as well as the browns.[20]

Most of the simpler algae are unicellular flagellates or amoeboids, but colonial and nonmotile forms have developed independently among several of the groups. Some of the more common organizational levels, more than one of which may occur in the lifecycle of a species, are

- Colonial: small, regular groups of motile cells

- Capsoid: individual non-motile cells embedded in mucilage

- Coccoid: individual non-motile cells with cell walls

- Palmelloid: nonmotile cells embedded in mucilage

- Filamentous: a string of connected nonmotile cells, sometimes branching

- Parenchymatous: cells forming a thallus with partial differentiation of tissues

In three lines, even higher levels of organization have been reached, with full tissue differentiation. These are the brown algae,[21]—some of which may reach 50 m in length (kelps)[22]—the red algae,[23] and the green algae.[24] The most complex forms are found among the charophyte algae (see Charales and Charophyta), in a lineage that eventually led to the higher land plants. The innovation that defines these nonalgal plants is the presence of female reproductive organs with protective cell layers that protect the zygote and developing embryo. Hence, the land plants are referred to as the Embryophytes.

Turfs

[edit]The term algal turf is commonly used but poorly defined. Algal turfs are thick, carpet-like beds of seaweed that retain sediment and compete with foundation species like corals and kelps, and they are usually less than 15 cm tall. Such a turf may consist of one or more species, and will generally cover an area in the order of a square metre or more. Some common characteristics are listed:[25]

- Algae that form aggregations that have been described as turfs include diatoms, cyanobacteria, chlorophytes, phaeophytes and rhodophytes. Turfs are often composed of numerous species at a wide range of spatial scales, but monospecific turfs are frequently reported.[25]

- Turfs can be morphologically highly variable over geographic scales and even within species on local scales and can be difficult to identify in terms of the constituent species.[25]

- Turfs have been defined as short algae, but this has been used to describe height ranges from less than 0.5 cm to more than 10 cm. In some regions, the descriptions approached heights which might be described as canopies (20 to 30 cm).[25]

Physiology

[edit]Many algae, particularly species of the Characeae,[26] have served as model experimental organisms to understand the mechanisms of the water permeability of membranes, osmoregulation, salt tolerance, cytoplasmic streaming, and the generation of action potentials. Plant hormones are found not only in higher plants, but in algae, too.[27]

Life cycle

[edit]Rhodophyta, Chlorophyta, and Heterokontophyta, the three main algal divisions, have life cycles which show considerable variation and complexity. In general, an asexual phase exists where the seaweed's cells are diploid, a sexual phase where the cells are haploid, followed by fusion of the male and female gametes. Asexual reproduction permits efficient population increases, but less variation is possible. Commonly, in sexual reproduction of unicellular and colonial algae, two specialized, sexually compatible, haploid gametes make physical contact and fuse to form a zygote. To ensure a successful mating, the development and release of gametes is highly synchronized and regulated; pheromones may play a key role in these processes.[28] Sexual reproduction allows for more variation and provides the benefit of efficient recombinational repair of DNA damages during meiosis, a key stage of the sexual cycle.[29] However, sexual reproduction is more costly than asexual reproduction.[30] Meiosis has been shown to occur in many different species of algae.[31]

Diversity

[edit]The most recent estimate (as of January 2024) documents 50,605 living and 10,556 fossil algal species, according to the online database AlgaeBase.[b] They are classified into 15 phyla or divisions. Some phyla are not photosynthetic, namely Picozoa and Rhodelphidia, but they are included in the database due to their close relationship with red algae.[1][35]

| phylum (division) | described genera |

described species | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| living | fossil | total | ||

| "Charophyta" (Streptophyta without land plants) | 236 | 4,940 | 704 | 5,644 |

| Chlorarachniophyta | 10[b] | 16[b] | 0 | 16[b] |

| Chlorophyta | 1,513 | 6,851 | 1,083 | 7,934 |

| Chromeridophyta | 6 | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Cryptophyta | 44 | 245 | 0 | 245 |

| Cyanobacteria | 866 | 4,669 | 1,054 | 5,723 |

| Dinoflagellata (Dinophyta) | 710 | 2,956 | 955 | 3,911 |

| Euglenophyta (not all species are algae) | 164 | 2,037 | 20 | 2,057 |

| Glaucophyta | 8 | 25 | 0 | 25 |

| Haptophyta | 391 | 517 | 1205 | 1,722 |

| Heterokontophyta | 1,781 | 21,052 | 2,262 | 23,314 |

| Picozoa (Picobiliphyta) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Prasinodermophyta | 5 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Rhodelphidia | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Rhodophyta | 1,094 | 7,276 | 278 | 7,554 |

| Incertae sedis fossils | 887 | 0 | 2,995 | 2,995 |

| Total | 7,717 | 50,605 | 10,556 | 61,161 |

The various algal phyla can be differentiated according to several biological traits. They have distinct morphologies, photosynthetic pigmentation, storage products, cell wall composition,[19] and mechanisms of carbon concentration.[36] Some phyla have unique cellular structures.[19]

Prokaryotic algae

[edit]Among prokaryotes, five major groups of bacteria have evolved the ability to photosynthesize, including heliobacteria, green sulfur and nonsulfur bacteria and proteobacteria.[38] However, the only lineage where oxygenic photosynthesis has evolved is in the cyanobacteria,[39] named for their blue-green (cyan) coloration and often known as blue-green algae.[40] They are classified as the phylum Cyanobacteriota or Cyanophyta. However, this phylum also includes two classes of non-photosynthetic bacteria: Melainabacteria[41] (also called Vampirovibrionia[42] or Vampirovibrionophyceae)[43] and Sericytochromatia[44] (also known as Blackallbacteria).[45] A third class contains the photosynthetic ones, known as Cyanophyceae[43] (also called Cyanobacteriia[42] or Oxyphotobacteria).[44]

As bacteria, their cells lack membrane-bound organelles, with the exception of thylakoids. Like other algae, cyanobacteria have chlorophyll a as their primary photosynthetic pigment. Their accessory pigments include phycobilins (phycoerythrobilin and phycocyanobilin), carotenoids and, in some cases, b, d, or f chlorophylls, generally distributed in phycobilisomes found in the surface of thylakoids. They display a variety of body forms, such as single cells, colonies, and unbranched or branched filaments. Their cells are commonly covered in a sheath of mucilage, and they also have a typical gram-negative bacterial cell wall composed largely of peptidoglycan. They have various storage particles, including cyanophycin as aminoacid and nitrogen reserves, "cyanophycean starch" (similar to plant amylose) for carbohydrates, and lipid droplets. Their Rubisco enzymes are concentrated in carboxysomes. They occupy a diverse array of aquatic and terrestrial habitats, including extreme environments from hot springs to polar glaciers. Some are subterranean, living via hydrogen-based lithoautotrophy instead of photosynthesis.[40]

Three lineages of cyanobacteria, Prochloraceae, Prochlorothrix and Prochlorococcus, independently evolved to have chlorophylls a and b instead of phycobilisomes. Due to their different pigmentation, they were historically grouped in a separate division, Prochlorophyta, as this is the typical pigmentation seen in green algae (e.g., chlorophytes). Eventually, this classification became obsolete, as it is a polyphyletic grouping.[46][47]

Cyanobacteria are included as algae by most phycological sources[18][19][1] and by the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants,[48] although a few authors exclude them from the definition of algae and reserve the term for eukaryotes only.[4][49]

Eukaryotic algae

[edit]Eukaryotic algae contain chloroplasts that are similar in structure to cyanobacteria. Chloroplasts contain circular DNA like that in cyanobacteria and are interpreted as representing reduced endosymbiotic cyanobacteria. However, the exact origin of the chloroplasts is different among separate lineages of algae, reflecting their acquisition during different endosymbiotic events. Many groups contain some members that are no longer photosynthetic. Some retain plastids, but not chloroplasts, while others have lost plastids entirely.[50]

Primary algae

[edit]These algae, grouped in the clade Archaeplastida (meaning 'ancient plastid'), have "primary chloroplasts", i.e. the chloroplasts are surrounded by two membranes and probably developed through a single endosymbiotic event with a cyanobacterium. The chloroplasts of red algae have chlorophylls a and c (often), and phycobilins, while those of green algae have chloroplasts with chlorophyll a and b without phycobilins. Land plants are pigmented similarly to green algae and probably developed from them, thus the Chlorophyta is a sister taxon to the plants; sometimes the Chlorophyta, the Charophyta, and land plants are grouped together as the Viridiplantae.[citation needed]

There is also a minor group of algae with primary plastids of different origin than the chloroplasts of the archaeplastid algae. The photosynthetic plastid of three species of the genus Paulinella (Rhizaria – Cercozoa – Euglyphida), often referred to as a 'cyanelle', was originated in the endosymbiosis of a α-cyanobacterium (probably an ancestral member of Chroococcales).[51][52]

Secondary algae

[edit]These algae appeared independently in various distantly related lineages after acquiring a chloroplast derived from another eukaryotic alga. Two lineages of secondary algae, chlorarachniophytes and euglenophytes have "green" chloroplasts containing chlorophylls a and b.[53] Their chloroplasts are surrounded by four and three membranes, respectively, and were probably retained from ingested green algae.[54][55][56]

- Chlorarachniophytes, which belong to the phylum Cercozoa, contain a small nucleomorph, which is a relict of the algae's nucleus.[57]

- Euglenophytes, which belong to the phylum Euglenozoa, live primarily in fresh water and have chloroplasts with only three membranes. The endosymbiotic green algae may have been acquired through myzocytosis rather than phagocytosis.[58]

- Another group with green algae endosymbionts is the dinoflagellate genus Lepidodinium, which has replaced its original endosymbiont of red algal origin with one of green algal origin. A nucleomorph is present, and the host genome still have several red algal genes acquired through endosymbiotic gene transfer. Also, the euglenid and chlorarachniophyte genome contain genes of apparent red algal ancestry.[59][60][61]

Other groups have "red" chloroplasts containing chlorophylls a and c, and phycobilins. The shape can vary; they may be of discoid, plate-like, reticulate, cup-shaped, spiral, or ribbon shaped. They have one or more pyrenoids to preserve protein and starch. The latter chlorophyll type is not known from any prokaryotes or primary chloroplasts, but genetic similarities with red algae suggest a relationship there.[62] In some of these groups, the chloroplast has four membranes, retaining a nucleomorph in cryptomonads, and they likely share a common pigmented ancestor, although other evidence casts doubt on whether the heterokonts, Haptophyta, and cryptomonads are in fact more closely related to each other than to other groups.[63][64]

The typical dinoflagellate chloroplast has three membranes, but considerable diversity exists in chloroplasts within the group, and a number of endosymbiotic events apparently occurred.[5] The Apicomplexa, a group of closely related parasites, also have plastids called apicoplasts, which are not photosynthetic.[5] The Chromerida are the closest relatives of apicomplexans, and some have retained their chloroplasts.[65] The three alveolate groups evolved from a common myzozoan ancestor that obtained chloroplasts.[66]

History of classification

[edit]

Linnaeus, in Species Plantarum (1753),[67] the starting point for modern botanical nomenclature, recognized 14 genera of algae, of which only four are currently considered among algae.[68] In Systema Naturae, Linnaeus described the genera Volvox and Corallina, and a species of Acetabularia (as Madrepora), among the animals.

In 1768, Samuel Gottlieb Gmelin (1744–1774) published the Historia Fucorum, the first work dedicated to marine algae and the first book on marine biology to use the then new binomial nomenclature of Linnaeus. It included elaborate illustrations of seaweed and marine algae on folded leaves.[69][70]

W. H. Harvey (1811–1866) and Lamouroux (1813)[71] were the first to divide macroscopic algae into four divisions based on their pigmentation. This is the first use of a biochemical criterion in plant systematics. Harvey's four divisions are: red algae (Rhodospermae), brown algae (Melanospermae), green algae (Chlorospermae), and Diatomaceae.[72][73]

At this time, microscopic algae were discovered and reported by a different group of workers (e.g., O. F. Müller and Ehrenberg) studying the Infusoria (microscopic organisms). Unlike macroalgae, which were clearly viewed as plants, microalgae were frequently considered animals because they are often motile.[71] Even the nonmotile (coccoid) microalgae were sometimes merely seen as stages of the lifecycle of plants, macroalgae, or animals.[74][75]

Although used as a taxonomic category in some pre-Darwinian classifications, e.g., Linnaeus (1753),[76] de Jussieu (1789),[77] Lamouroux (1813), Harvey (1836), Horaninow (1843), Agassiz (1859), Wilson & Cassin (1864),[76] in further classifications, the "algae" are seen as an artificial, polyphyletic group.[78]

Throughout the 20th century, most classifications treated the following groups as divisions or classes of algae: cyanophytes, rhodophytes, chrysophytes, xanthophytes, bacillariophytes, phaeophytes, pyrrhophytes (cryptophytes and dinophytes), euglenophytes, and chlorophytes. Later, many new groups were discovered (e.g., Bolidophyceae), and others were splintered from older groups: charophytes and glaucophytes (from chlorophytes), many heterokontophytes (e.g., synurophytes from chrysophytes, or eustigmatophytes from xanthophytes), haptophytes (from chrysophytes), and chlorarachniophytes (from xanthophytes).[79]

With the abandonment of plant-animal dichotomous classification, most groups of algae (sometimes all) were included in Protista, later also abandoned in favour of Eukaryota. However, as a legacy of the older plant life scheme, some groups that were also treated as protozoans in the past still have duplicated classifications (see ambiregnal protists).[80]

Some parasitic algae (e.g., the green algae Prototheca and Helicosporidium, parasites of metazoans, or Cephaleuros, parasites of plants) were originally classified as fungi, sporozoans, or protistans of incertae sedis,[81] while others (e.g., the green algae Phyllosiphon and Rhodochytrium, parasites of plants, or the red algae Pterocladiophila and Gelidiocolax mammillatus, parasites of other red algae, or the dinoflagellates Oodinium, parasites of fish) had their relationship with algae conjectured early. In other cases, some groups were originally characterized as parasitic algae (e.g., Chlorochytrium), but later were seen as endophytic algae.[82] Some filamentous bacteria (e.g., Beggiatoa) were originally seen as algae. Furthermore, groups like the apicomplexans are also parasites derived from ancestors that possessed plastids, but are not included in any group traditionally seen as algae.[83][84]

Evolution

[edit]Origin of oxygenic photosynthesis

[edit]Prokaryotic algae, i.e., cyanobacteria, are the only group of organisms where oxygenic photosynthesis has evolved. The oldest undisputed fossil evidence of cyanobacteria is dated at 2100 million years ago,[85] although stromatolites, associated with cyanobacterial biofilms, appear as early as 3500 million years ago in the fossil record.[86]

First endosymbiosis

[edit]Eukaryotic algae are polyphyletic thus their origin cannot be traced back to single hypothetical common ancestor. It is thought that they came into existence when photosynthetic coccoid cyanobacteria got phagocytized by a unicellular heterotrophic eukaryote (a protist),[87] giving rise to double-membranous primary plastids. Such symbiogenic events (primary symbiogenesis) are believed to have occurred more than 1.5 billion years ago during the Calymmian period, early in Boring Billion, but it is difficult to track the key events because of so much time gap.[88] Primary symbiogenesis gave rise to three divisions of archaeplastids, namely the Viridiplantae (green algae and later plants), Rhodophyta (red algae) and Glaucophyta ("grey algae"), whose plastids further spread into other protist lineages through eukaryote-eukaryote predation, engulfments and subsequent endosymbioses (secondary and tertiary symbiogenesis).[88] This process of serial cell "capture" and "enslavement" explains the diversity of photosynthetic eukaryotes.[87] The oldest undisputed fossil evidence of eukaryotic algae is Bangiomorpha pubescens, a red alga found in rocks around 1047 million years old.[89][90]

Consecutive endosymbioses

[edit]

Recent genomic and phylogenomic approaches have significantly clarified plastid genome evolution, the horizontal movement of endosymbiont genes to the "host" nuclear genome, and plastid spread throughout the eukaryotic tree of life.[87] It is accepted that both euglenophytes and chlorarachniophytes obtained their chloroplasts from chlorophytes that became endosymbionts.[93] In particular, euglenophyte chloroplasts share the most resemblance with the genus Pyramimonas.[94]

However, there is still no clear order in which the secondary and tertiary endosymbioses occurred for the "chromist" lineages (ochrophytes, cryptophytes, haptophytes and myzozoans).[95] Two main models have been proposed to explain the order, both of which agree that cryptophytes obtained their chloroplasts from red algae. One model, hypothesized in 2014 by John W. Stiller and coauthors,[96] suggests that a cryptophyte became the plastid of ochrophytes, which in turn became the plastid of myzozoans and haptophytes. The other model, suggested by Andrzej Bodył and coauthors in 2009,[97] describes that a cryptophyte became the plastid of both haptophytes and ochrophytes, and it is a haptophyte that became the plastid of myzozoans instead.[92] In 2024, a third model by Filip Pietluch and coauthors proposed that there were two independent endosymbioses with red algae: one that originated the cryptophyte plastids (as in the previous models), and subsequently the haptophyte plastids; and another that originated the ochrophyte plastids, where the myzozoans obtained theirs.[91]

Relationship to land plants

[edit]Fossils of isolated spores suggest land plants may have been around as long as 475 million years ago (mya) during the Late Cambrian/Early Ordovician period,[98][99] from sessile shallow freshwater charophyte algae much like Chara,[100] which likely got stranded ashore when riverine/lacustrine water levels dropped during dry seasons.[101] These charophyte algae probably already developed filamentous thalli and holdfasts that superficially resembled plant stems and roots, and probably had an isomorphic alternation of generations. They perhaps evolved some 850 mya[102] and might even be as early as 1 Gya during the late phase of the Boring Billion.[103]

Distribution

[edit]The distribution of algal species has been fairly well studied since the founding of phytogeography in the mid-19th century.[104] Algae spread mainly by the dispersal of spores analogously to the dispersal of cryptogamic plants by spores. Spores can be found in a variety of environments: fresh and marine waters, air, soil, and in or on other organisms.[104] Whether a spore is to grow into an adult organism depends on the species and the environmental conditions where the spore lands.

The spores of freshwater algae are dispersed mainly by running water and wind, as well as by living carriers.[104] However, not all bodies of water can carry all species of algae, as the chemical composition of certain water bodies limits the algae that can survive within them.[104] Marine spores are often spread by ocean currents. Ocean water presents many vastly different habitats based on temperature and nutrient availability, resulting in phytogeographic zones, regions, and provinces.[105]

To some degree, the distribution of algae is subject to floristic discontinuities caused by geographical features, such as Antarctica, long distances of ocean or general land masses. It is, therefore, possible to identify species occurring by locality, such as "Pacific algae" or "North Sea algae". When they occur out of their localities, hypothesizing a transport mechanism is usually possible, such as the hulls of ships. For example, Ulva reticulata and U. fasciata travelled from the mainland to Hawaii in this manner.

Mapping is possible for select species only: "there are many valid examples of confined distribution patterns."[106] For example, Clathromorphum is an arctic genus and is not mapped far south of there.[where?][107] However, scientists regard the overall data as insufficient due to the "difficulties of undertaking such studies."[108]

Regional algae checklists

[edit]

The Algal Collection of the US National Herbarium (located in the National Museum of Natural History) consists of approximately 320,500 dried specimens, which, although not exhaustive (no exhaustive collection exists), gives an idea of the order of magnitude of the number of algal species (that number remains unknown).[109] Estimates vary widely. For example, according to one standard textbook,[110] in the British Isles, the UK Biodiversity Steering Group Report estimated there to be 20,000 algal species in the UK. Another checklist reports only about 5,000 species. Regarding the difference of about 15,000 species, the text concludes: "It will require many detailed field surveys before it is possible to provide a reliable estimate of the total number of species ..."

Regional and group estimates have been made, as well:

- 5,000–5,500 species of red algae worldwide[citation needed]

- "some 1,300 in Australian Seas"[111]

- 400 seaweed species for the western coastline of South Africa,[112] and 212 species from the coast of KwaZulu-Natal.[113] Some of these are duplicates, as the range extends across both coasts, and the total recorded is probably about 500 species. Most of these are listed in List of seaweeds of South Africa. These exclude phytoplankton and crustose corallines.

- 669 marine species from California (US)[114]

- 642 in the check-list of Britain and Ireland[115]

and so on, but lacking any scientific basis or reliable sources, these numbers have no more credibility than the British ones mentioned above. Most estimates also omit microscopic algae, such as phytoplankton.[citation needed]

Ecology

[edit]

Algae are prominent in bodies of water, common in terrestrial environments, and are found in unusual environments, such as on snow and ice. Seaweeds grow mostly in shallow marine waters, less than100 m (330 ft) deep; however, some such as Navicula pennata have been recorded to a depth of 360 m (1,180 ft).[116] A type of algae, Ancylonema nordenskioeldii, was found in Greenland in areas known as the 'Dark Zone', which caused an increase in the rate of melting ice sheet.[117] The same algae was found in the Italian Alps, after pink ice appeared on parts of the Presena glacier.[118]

The various sorts of algae play significant roles in aquatic ecology. Microscopic forms that live suspended in the water column (phytoplankton) provide the food base for most marine food chains. In very high densities (algal blooms), these algae may discolor the water and outcompete, poison, or asphyxiate other life forms.[119]

Algae can be used as indicator organisms to monitor pollution in various aquatic systems.[120] In many cases, algal metabolism is sensitive to various pollutants. Due to this, the species composition of algal populations may shift in the presence of chemical pollutants.[120] To detect these changes, algae can be sampled from the environment and maintained in laboratories with relative ease.[120]

On the basis of their habitat, algae can be categorized as: aquatic (planktonic, benthic, marine, freshwater, lentic, lotic),[121] terrestrial, aerial (subaerial),[122] lithophytic, halophytic (or euryhaline), psammon, thermophilic, cryophilic, epibiont (epiphytic, epizoic), endosymbiont (endophytic, endozoic), parasitic, calcifilic or lichenic (phycobiont).[123]

Symbiotic algae

[edit]Some species of algae form symbiotic relationships with other organisms. In these symbioses, the algae supply photosynthates (organic substances) to the host organism providing protection to the algal cells. The host organism derives some or all of its energy requirements from the algae.[citation needed] Examples are:

Lichens

[edit]

Lichens are defined by the International Association for Lichenology to be "an association of a fungus and a photosynthetic symbiont resulting in a stable vegetative body having a specific structure".[124] The fungi, or mycobionts, are mainly from the Ascomycota with a few from the Basidiomycota. In nature, they do not occur separate from lichens. It is unknown when they began to associate.[125] One or more[126] mycobiont associates with the same phycobiont species, from the green algae, except that alternatively, the mycobiont may associate with a species of cyanobacteria (hence "photobiont" is the more accurate term). A photobiont may be associated with many different mycobionts or may live independently; accordingly, lichens are named and classified as fungal species.[127] The association is termed a morphogenesis because the lichen has a form and capabilities not possessed by the symbiont species alone (they can be experimentally isolated). The photobiont possibly triggers otherwise latent genes in the mycobiont.[128]

Trentepohlia is an example of a common green alga genus worldwide that can grow on its own or be lichenised. Lichen thus share some of the habitat and often similar appearance with specialized species of algae (aerophytes) growing on exposed surfaces such as tree trunks and rocks and sometimes discoloring them.[citation needed]

Animal symbioses

[edit]

Coral reefs are accumulated from the calcareous exoskeletons of marine invertebrates of the order Scleractinia (stony corals). These animals metabolize sugar and oxygen to obtain energy for their cell-building processes, including secretion of the exoskeleton, with water and carbon dioxide as byproducts. Dinoflagellates (algal protists) are often endosymbionts in the cells of the coral-forming marine invertebrates, where they accelerate host-cell metabolism by generating sugar and oxygen immediately available through photosynthesis using incident light and the carbon dioxide produced by the host. Reef-building stony corals (hermatypic corals) require endosymbiotic algae from the genus Symbiodinium to be in a healthy condition.[129] The loss of Symbiodinium from the host is known as coral bleaching, a condition which leads to the deterioration of a reef.

Endosymbiontic green algae live close to the surface of some sponges, for example, breadcrumb sponges (Halichondria panicea). The alga is thus protected from predators; the sponge is provided with oxygen and sugars which can account for 50 to 80% of sponge growth in some species.[130]

In human culture

[edit]In classical Chinese, the word 藻 is used both for "algae" and (in the modest tradition of the imperial scholars) for "literary talent". The third island in Kunming Lake beside the Summer Palace in Beijing is known as the Zaojian Tang Dao (藻鑒堂島), which thus simultaneously means "Island of the Algae-Viewing Hall" and "Island of the Hall for Reflecting on Literary Talent".[citation needed]

Cultivation

[edit]

Algaculture is a form of aquaculture involving the farming of species of algae.[131]

The majority of algae that are intentionally cultivated fall into the category of microalgae (also referred to as phytoplankton, microphytes, or planktonic algae). Macroalgae, commonly known as seaweed, also have many commercial and industrial uses, but due to their size and the specific requirements of the environment in which they need to grow, they do not lend themselves as readily to cultivation (this may change, however, with the advent of newer seaweed cultivators, which are basically algae scrubbers using upflowing air bubbles in small containers, known as tumble culture).[132]

Commercial and industrial algae cultivation has numerous uses, including production of nutraceuticals such as omega-3 fatty acids (as algal oil)[133][134][135] or natural food colorants and dyes, food, fertilizers, bioplastics, chemical feedstock (raw material), protein-rich animal/aquaculture feed, pharmaceuticals, and algal fuel,[136] and can also be used as a means of pollution control and natural carbon sequestration.[137]

Global production of farmed aquatic plants, overwhelmingly dominated by seaweeds, grew in output volume from 13.5 million tonnes in 1995, to just over 30 million tonnes in 2016 and 37.8 million tonnes in 2022.[138][139] This increase was the result of production expansions led by China, followed by Malaysia, the Philippines, the United Republic of Tanzania, and the Russian Federation.[138]

Cultured microalgae already contribute to a wide range of sectors in the emerging bioeconomy.[140] Research suggests there are large potentials and benefits of algaculture for the development of a future healthy and sustainable food system.[141][137]Seaweed farming

[edit]

Seaweed farming or kelp farming is the practice of cultivating and harvesting seaweed. In its simplest form farmers gather from natural beds, while at the other extreme farmers fully control the crop's life cycle.

The seven most cultivated taxa are Eucheuma spp., Kappaphycus alvarezii, Gracilaria spp., Saccharina japonica, Undaria pinnatifida, Pyropia spp., and Sargassum fusiforme. Eucheuma and K. alvarezii are attractive for carrageenan (a gelling agent); Gracilaria is farmed for agar; the rest are eaten after limited processing.[142] Seaweeds are different from mangroves and seagrasses, as they are photosynthetic algal organisms[143] and are non-flowering.[142]

The largest seaweed-producing countries as of 2022 are China (58.62%) and Indonesia (28.6%); followed by South Korea (5.09%) and the Philippines (4.19%). Other notable producers include North Korea (1.6%), Japan (1.15%), Malaysia (0.53%), Zanzibar (Tanzania, 0.5%), and Chile (0.3%).[144][145] Seaweed farming has frequently been developed to improve economic conditions and to reduce fishing pressure.[146]

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported that world production in 2019 was over 35 million tonnes. North America produced some 23,000 tonnes of wet seaweed. Alaska, Maine, France, and Norway each more than doubled their seaweed production since 2018. As of 2019, seaweed represented 30% of marine aquaculture.[147] In 2023, the global seaweed extract market was valued at $16.5 billion, with strong projected growth.[148]

Seaweed farming is a carbon negative crop, with a high potential for climate change mitigation.[149][150] The IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate recommends "further research attention" as a mitigation tactic.[151] World Wildlife Fund, Oceans 2050, and The Nature Conservancy publicly support expanded seaweed cultivation.[147]Bioreactors

[edit]

Uses

[edit]

Biofuel

[edit]To be competitive and independent from fluctuating support from (local) policy on the long run, biofuels should equal or beat the cost level of fossil fuels. Here, algae-based fuels hold great promise,[153][154] directly related to the potential to produce more biomass per unit area in a year than any other form of biomass. The break-even point for algae-based biofuels is estimated to occur by 2025.[155]

Fertilizer

[edit]

For centuries, seaweed has been used as a fertilizer; George Owen of Henllys writing in the 16th century referring to drift weed in South Wales:[156]

This kind of ore they often gather and lay on great heapes, where it heteth and rotteth, and will have a strong and loathsome smell; when being so rotten they cast on the land, as they do their muck, and thereof springeth good corn, especially barley ... After spring-tydes or great rigs of the sea, they fetch it in sacks on horse backes, and carie the same three, four, or five miles, and cast it on the lande, which doth very much better the ground for corn and grass.

Today, algae are used by humans in many ways; for example, as fertilizers, soil conditioners, and livestock feed.[157] Aquatic and microscopic species are cultured in clear tanks or ponds and are either harvested or used to treat effluents pumped through the ponds. Algaculture on a large scale is an important type of aquaculture in some places. Maerl is commonly used as a soil conditioner.[158]

Food industry

[edit]Algae are used as foods in many countries: China consumes more than 70 species, including fat choy, a cyanobacterium considered a vegetable; Japan, over 20 species such as nori and aonori;[159] Ireland, dulse; Chile, cochayuyo.[160] Laver is used to make laverbread in Wales, where it is known as bara lawr. In Korea, green laver is used to make gim.[161]

Three forms of algae used as food:

- Chlorella: This form of alga is found in freshwater and contains photosynthetic pigments in its chloroplasts.[162]

- Klamath AFA: A subspecies of Aphanizomenon flos-aquae found wild in many bodies of water worldwide but harvested only from Upper Klamath Lake, Oregon.[163]

- Spirulina: Known otherwise as a cyanobacterium (a prokaryote or a "blue-green alga")[164]

The oils from some algae have high levels of unsaturated fatty acids. Some varieties of algae favored by vegetarianism and veganism contain the long-chain, essential omega-3 fatty acids, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA).[165] Fish oil contains the omega-3 fatty acids, but the original source is algae (microalgae in particular), which are eaten by marine life such as copepods and are passed up the food chain.[165]

The natural pigments (carotenoids and chlorophylls) produced by algae can be used as alternatives to chemical dyes and coloring agents.[166] The presence of some individual algal pigments, together with specific pigment concentration ratios, are taxon-specific: analysis of their concentrations with various analytical methods, particularly high-performance liquid chromatography, can therefore offer deep insight into the taxonomic composition and relative abundance of natural algae populations in sea water samples.[167][168]

Carrageenan, from the red alga Chondrus crispus, is used as a stabilizer in milk products.[citation needed]

Gelling agents

[edit]Agar, a gelatinous substance derived from red algae, has a number of commercial uses.[169] It is a good medium on which to grow bacteria and fungi, as most microorganisms cannot digest agar.[170]

Alginic acid, or alginate, is extracted from brown algae. Its uses range from gelling agents in food, to medical dressings. Alginic acid also has been used in the field of biotechnology as a biocompatible medium for cell encapsulation and cell immobilization. Molecular cuisine is also a user of the substance for its gelling properties, by which it becomes a delivery vehicle for flavours.[171]

Between 100,000 and 170,000 wet tons of Macrocystis are harvested annually in New Mexico for alginate extraction and abalone feed.[172][173]

Pollution control and bioremediation

[edit]- Sewage can be treated with algae,[174] reducing the use of large amounts of toxic chemicals that would otherwise be needed.

- Algae can be used to capture fertilizers in runoff from farms. When subsequently harvested, the enriched algae can be used as fertilizer.[175]

- Aquaria and ponds can be filtered using algae, which absorb nutrients from the water in a device called an algae scrubber, also known as an algae turf scrubber.[176][177]

Agricultural Research Service scientists found that 60–90% of nitrogen runoff and 70–100% of phosphorus runoff can be captured from manure effluents using a horizontal algae scrubber, also called an algal turf scrubber (ATS). Scientists developed the ATS, which consists of shallow, 100-foot raceways of nylon netting where algae colonies can form, and studied its efficacy for three years. They found that algae can readily be used to reduce the nutrient runoff from agricultural fields and increase the quality of water flowing into rivers, streams, and oceans. Researchers collected and dried the nutrient-rich algae from the ATS and studied its potential as an organic fertilizer. They found that cucumber and corn seedlings grew just as well using ATS organic fertilizer as they did with commercial fertilizers.[178] Algae scrubbers, using bubbling upflow or vertical waterfall versions, are now also being used to filter aquaria and ponds.[citation needed]

The alga Stichococcus bacillaris has been seen to colonize silicone resins used at archaeological sites; biodegrading the synthetic substance.[179]

Bioplastics

[edit]Various polymers can be created from algae, which can be especially useful in the creation of bioplastics. These include hybrid plastics, cellulose-based plastics, poly-lactic acid, and bio-polyethylene.[180] Several companies have begun to produce algae polymers commercially, including for use in flip-flops[181] and in surf boards.[182] Even algae is also used to prepare various polymeric resins suitable for coating applications.[183][184][185]

Additional images

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Some botanists restrict the name algae to eukaryotes, which does not include cyanobacteria, which are prokaryotes.[citation needed]

- ^ a b c d Chlorarachniophytes were omitted from the 2024 AlgaeBase species report. The numbers shown here for the order Chlorarachniales were obtained from the 13th edition of Syllabus der Pflanzenfamilien (2015), where it contains 8 genera and 14 species total.[32] The two remaining chlorarachniophyte genera, Minorisa and Rhabdamoeba, have one species each.[33][34]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Guiry, Michael D. (2024). "How many species of algae are there? A reprise. Four kingdoms, 14 phyla, 63 classes and still growing". Journal of Phycology. 60 (2): 214–228. Bibcode:2024JPcgy..60..214G. doi:10.1111/jpy.13431. PMID 38245909.

- ^ Guiry, M.D. & Guiry, G.M. 2025. AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, University of Galway. https://www.algaebase.org; searched on 25 May 2025.

- ^ "ALGAE | English meaning - Cambridge Dictionary". Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ a b Nabors, Murray W. (2004). Introduction to Botany. San Francisco: Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8053-4416-5.

- ^ a b c Keeling, Patrick J. (2004). "Diversity and evolutionary history of plastids and their hosts". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1481–1493. Bibcode:2004AmJB...91.1481K. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1481. PMID 21652304.

- ^ Palmer, J. D.; Soltis, D. E.; Chase, M. W. (2004). "The plant tree of life: an overview and some points of view". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1437–1445. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1437. PMID 21652302.

- ^ Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History; Department of Botany. "Algae Research". Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ Pringsheim, E. G. 1963. Farblose Algen. Ein beitrag zur Evolutionsforschung. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart. 471 pp., species:Algae#Pringsheim (1963).

- ^ Tartar, A.; Boucias, D. G.; Becnel, J. J.; Adams, B. J. (2003). "Comparison of plastid 16S rRNA (rrn 16) genes from Helicosporidium spp.: Evidence supporting the reclassification of Helicosporidia as green algae (Chlorophyta)". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (Pt 6): 1719–1723. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02559-0. PMID 14657099.

- ^ Figueroa-Martinez, F.; Nedelcu, A. M.; Smith, D. R.; Reyes-Prieto, A. (2015). "When the lights go out: the evolutionary fate of free-living colorless green algae". New Phytologist. 206 (3): 972–982. Bibcode:2015NewPh.206..972F. doi:10.1111/nph.13279. PMC 5024002. PMID 26042246.

- ^ Bengtson, S.; Belivanova, V.; Rasmussen, B.; Whitehouse, M. (2009). "The controversial 'Cambrian' fossils of the Vindhyan are real but more than a billion years older". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (19): 7729–7734. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.7729B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812460106. PMC 2683128. PMID 19416859.

- ^ Paul, Vishal; Chandra Shekharaiah, P. S.; Kushwaha, Shivbachan; Sapre, Ajit; Dasgupta, Santanu; Sanyal, Debanjan (2020). "Role of Algae in CO2 Sequestration Addressing Climate Change: A Review". In Deb, Dipankar; Dixit, Ambesh; Chandra, Laltu (eds.). Renewable Energy and Climate Change. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies. Vol. 161. Singapore: Springer. pp. 257–265. doi:10.1007/978-981-32-9578-0_23. ISBN 978-981-329-578-0. S2CID 202902934.

- ^ "alga, algae". Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged with Seven Language Dictionary. Vol. 1. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1986.

- ^ Partridge, Eric (1983). "algae". Origins. Greenwich House. ISBN 9780517414255.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879). "Alga". A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ Cheyne, Thomas Kelly; Black, John Sutherland (1902). Encyclopædia biblica: A critical dictionary of the literary, political and religious history, the archæology, geography, and natural history of the Bible. Macmillan Company. p. 3525.

- ^ Lee, Robert Edward, ed. (2008), "Basic characteristics of the algae", Phycology (4 ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–30, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511812897.002, ISBN 978-1-107-79688-1, retrieved 13 September 2023

- ^ a b Lee, Robert Edward (2008). Phycology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521367448.

- ^ a b c d e f Graham, Linda E.; Graham, James M.; Wilcox, Lee W.; Cook, Martha E. (2022). "Chapter 1. Introduction to the Algae". Algae (4th ed.). LJLM Press. ISBN 978-0-9863935-4-9.

- ^ a b c d Xiao, S.; Knoll, A. H.; Yuan, X.; Pueschel, C. M. (2004). "Phosphatized multicellular algae in the Neoproterozoic Doushantuo Formation, China, and the early evolution of florideophyte red algae". American Journal of Botany. 91 (2): 214–227. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.2.214. PMID 21653378.

- ^ Waggoner, Ben (1994–2008). "Introduction to the Phaeophyta: Kelps and brown "Algae"". University of California Museum of Palaeontology (UCMP). Archived from the original on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- ^ Thomas, D. N. (2002). Seaweeds. London: The Natural History Museum. ISBN 978-0-565-09175-0.

- ^ Waggoner, Ben (1994–2008). "Introduction to the Rhodophyta, the red 'algae'". University of California Museum of Palaeontology (UCMP). Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- ^ "Introduction to the Green Algae". berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 13 February 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ^ a b c d Connell, Sean; Foster, M.S.; Airoldi, Laura (9 January 2014). "What are algal turfs? Towards a better description of turfs". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 495: 299–307. Bibcode:2014MEPS..495..299C. doi:10.3354/meps10513.

- ^ Tazawa, Masashi (2010). "Sixty Years Research with Characean Cells: Fascinating Material for Plant Cell Biology". Progress in Botany 72. Vol. 72. Springer. pp. 5–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13145-5_1. ISBN 978-3-642-13145-5. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ Tarakhovskaya, E. R.; Maslov, Yu. I.; Shishova, M. F. (April 2007). "Phytohormones in algae". Russian Journal of Plant Physiology. 54 (2): 163–170. Bibcode:2007RuJPP..54..163T. doi:10.1134/s1021443707020021. S2CID 27373543.

- ^ Frenkel, J.; Vyverman, W.; Pohnert, G. (2014). "Pheromone signaling during sexual reproduction in algae". Plant J. 79 (4): 632–644. Bibcode:2014PlJ....79..632F. doi:10.1111/tpj.12496. PMID 24597605.

- ^ Bernstein, Harris; Byerly, Henry C.; Hopf, Frederic A.; Michod, Richard E. (20 September 1985). "Genetic Damage, Mutation, and the Evolution of Sex". Science. 229 (4719): 1277–1281. Bibcode:1985Sci...229.1277B. doi:10.1126/science.3898363. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 3898363.

- ^ Otto, S. P. (2009). "The evolutionary enigma of sex". Am. Nat. 174 (Suppl 1): S1 – S14. Bibcode:2009ANat..174S...1O. doi:10.1086/599084. PMID 19441962. S2CID 9250680. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017.

- ^ Heywood, P.; Magee, P. T. (1976). "Meiosis in protists: Some structural and physiological aspects of meiosis in algae, fungi, and protozoa". Bacteriol Rev. 40 (1): 190–240. doi:10.1128/MMBR.40.1.190-240.1976. PMC 413949. PMID 773364.

- ^ Kawai, Hiroshi; Nakayama, Takeshi (2015). "Division Chlorarachniophyta D.J.Hibberd & R.E.Norris / Cercozoa Cavalier-Smith". In Frey, Wolfgang (ed.). Syllabus of Plant Families: A. Engler's Syllabus der Pflanzenfamilien. Part 2/1: Photoautotrophic eukaryotic Algae: Glaucocystophyta, Cryptophyta, Dinophyta/Dinozoa, Haptophyta, Heterokontophyta/Ochrophyta, Chlorarachniophyta/Cercozoa, Euglenophyta/Euglenozoa, Chlorophyta, Streptophyta p.p. Stuttgart: Gebr. Borntraeger Verlagsbuchhandlung. ISBN 978-3-443-01083-6.

- ^ del Campo, Javier; Not, Fabrice; Forn, Irene; Sieracki, Michael E; Massana, Ramon (1 February 2013). "Taming the smallest predators of the oceans" (PDF). The ISME Journal. 7 (2): 351–358. Bibcode:2013ISMEJ...7..351D. doi:10.1038/ismej.2012.85. ISSN 1751-7362. PMC 3554395. PMID 22810060. Retrieved 20 May 2025.

- ^ Shiratori, Takashi; Ishida, Ken-ichiro (8 November 2023). "Rhabdamoeba marina is a heterotrophic relative of chlorarachnid algae". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 71 (2) e13010. doi:10.1111/jeu.13010. ISSN 1066-5234. PMID 37941507.

- ^ Guiry, M.D. & Guiry, G.M. 2025. AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, University of Galway. https://www.algaebase.org; searched on 4 June 2025.

- ^ Graham, Linda E.; Graham, James M.; Wilcox, Lee W.; Cook, Martha E. (2022). "Chapter 2. The Roles of Algae in Biochemistry". Algae (4th ed.). LJLM Press. ISBN 978-0-9863935-4-9.

- ^ Fidor, Anna; Konkel, Robert; Mazur-Marzec, Hanna (29 September 2019). "Bioactive Peptides Produced by Cyanobacteria of the Genus Nostoc: A Review". Marine Drugs. 17 (10): 561. doi:10.3390/md17100561. ISSN 1660-3397. PMC 6835634. PMID 31569531.

- ^ Gupta, Radhey S. (2003). "Evolutionary relationships among photosynthetic bacteria". Photosynthesis Research. 76 (1–3): 173–183. Bibcode:2003PhoRe..76..173G. doi:10.1023/A:1024999314839. PMID 16228576.

- ^ Castenholz, Richard W. (14 September 2015). "Oxygenic Photosynthetic Bacteria". Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., in association with Bergey's Manual Trust. p. 1. doi:10.1002/9781118960608.cbm00020. ISBN 9781118960608.

- ^ a b Graham, Linda E.; Graham, James M.; Wilcox, Lee W.; Cook, Martha E. (2022). "Chapter 6. Cyanobacteria". Algae (4th ed.). LJLM Press. ISBN 978-0-9863935-4-9.

- ^ Matheus Carnevali, Paula B.; Schulz, Frederik; Castelle, Cindy J.; Kantor, Rose S.; Shih, Patrick M.; Sharon, Itai; Santini, Joanne M.; Olm, Matthew R.; Amano, Yuki; Thomas, Brian C.; Anantharaman, Karthik; Burstein, David; Becraft, Eric D.; Stepanauskas, Ramunas; Woyke, Tanja; Banfield, Jillian F. (28 January 2019). "Hydrogen-based metabolism as an ancestral trait in lineages sibling to the Cyanobacteria" (PDF). Nature Communications. 10 (1): 463. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..463M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08246-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6349859. PMID 30692531. Retrieved 21 May 2025.

- ^ a b Soo, Rochelle M.; Hemp, James; Hugenholtz, Philip (2019). "Evolution of photosynthesis and aerobic respiration in the cyanobacteria". Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 140: 200–205. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.03.029. PMID 30930297.

- ^ a b Strunecký, Otakar; Ivanova, Anna Pavlovna; Mareš, Jan (2023). "An updated classification of cyanobacterial orders and families based on phylogenomic and polyphasic analysis". Journal of Phycology. 59 (1): 12–51. Bibcode:2023JPcgy..59...12S. doi:10.1111/jpy.13304. ISSN 0022-3646. PMID 36443823.

- ^ a b Soo, Rochelle M.; Hemp, James; Parks, Donovan H.; Fischer, Woodward W.; Hugenholtz, Philip (31 March 2017). "On the origins of oxygenic photosynthesis and aerobic respiration in Cyanobacteria". Science. 355 (6332): 1436–1440. Bibcode:2017Sci...355.1436S. doi:10.1126/science.aal3794. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28360330.

- ^ Pinevich, Alexander; Averina, Svetlana (2021). "New life for old discovery: amazing story about how bacterial predation on Chlorella resolved a paradox of dark cyanobacteria an gave the key to early history of oxygenic photosynthesis and aerobic respiration". Protistology. 15 (3): 107–126. doi:10.21685/1680-0826-2021-15-3-2.

- ^ Sciuto, Katia; Moro, Isabella (2015). "Cyanobacteria: the bright and dark sides of a charming group". Biodiversity and Conservation. 24 (4): 711–738. Bibcode:2015BiCon..24..711S. doi:10.1007/s10531-015-0898-4. ISSN 0960-3115.

- ^ Singh, K. (2021). "Salient features of Protochlorophyta". Innovative Research Thoughts. 7 (4): 70–77.

- ^ Turland, Nicholas J.; Wiersema, John H.; Barrie, Fred R.; Greuter, Werner; Hawksworth, David L.; Herendeen, Patrick S.; Knapp, Sandra; Kusber, Wolf-Henning; Li, De-Zhu; Marhold, Karol; May, Tom W.; McNeill, John; Monro, Anna M.; Prado, Jefferson; Price, Michelle J.; Smith, Gideon F., eds. (2018). International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017. Regnum Vegetabile. Vol. 159. Glashütten: Koeltz Botanical Books. doi:10.12705/Code.2018. hdl:10141/622572. ISBN 978-3-946583-16-5. Retrieved 21 May 2025. Preamble, paragraph 8:

The provisions of this Code apply to all organisms traditionally treated as algae, fungi, or plants, whether fossil or non-fossil, including blue-green algae (Cyanobacteria)

- ^ Allaby, M., ed. (1992). "Alga". The Concise Dictionary of Botany. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Sato, Naoki (27 May 2021). "Are Cyanobacteria an Ancestor of Chloroplasts or Just One of the Gene Donors for Plants and Algae?". Genes. 12 (6): 823. doi:10.3390/genes12060823. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 8227023. PMID 34071987.

- ^ Gabr, Arwa; Grossman, Arthur R.; Bhattacharya, Debashish (August 2020). "Paulinella, a model for understanding plastid primary endosymbiosis". Journal of Phycology. 56 (4): 837–843. Bibcode:2020JPcgy..56..837G. doi:10.1111/jpy.13003. ISSN 1529-8817. PMC 7734844. PMID 32289879.

- ^ Delaye, Luis; Valadez-Cano, Cecilio; Pérez-Zamorano, Bernardo (2016). "How Really Ancient Is Paulinella Chromatophora?". PLOS Currents. 8. doi:10.1371/currents.tol.e68a099364bb1a1e129a17b4e06b0c6b. ISSN 2157-3999. PMC 4866557. PMID 28515968.

- ^ Losos, Jonathan B.; Mason, Kenneth A.; Singer, Susan R. (2007). Biology (8 ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-304110-0.

- ^ Bicudo, Carlos E. de M.; Menezes, Mariângela (16 March 2016). "Phylogeny and Classification of Euglenophyceae: A Brief Review". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4: 17. Bibcode:2016FrEEv...4...17B. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00017.

- ^ Kalina, T (2001). "The origin of chloroplasts and the position of eukaryotic algae in the six- kingdom system of life". Czech Phycology. 1 (1): 1-4.

- ^ McFadden, Geoffrey I.; Gilson, Paul R.; Hofmann, Claudia J. B. (1997). "Division Chlorarachniophyta". Origins of Algae and their Plastids. Plant Systematics and Evolution. Vol. 11. pp. 175–185. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-6542-3_10. ISBN 978-3-211-83035-2.

- ^ Ishida, K; Green, B R; Cavalier-Smith, T (1999). "Diversification of a Chimaeric Algal Group, the Chlorarachniophytes: Phylogeny of Nuclear and Nucleomorph Small-Subunit rRNA Genes". Molecular Biology &Evolution. 16 (3): 321-331. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026113.

- ^ Archibald, J. M.; Keeling, P. J. (November 2002). "Recycled plastids: A 'green movement' in eukaryotic evolution". Trends in Genetics. 18 (11): 577–584. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02777-4. PMID 12414188.

- ^ O'Neill, Ellis C.; Trick, Martin; Henrissat, Bernard; Field, Robert A. (2015). "Euglena in time: Evolution, control of central metabolic processes and multi-domain proteins in carbohydrate and natural product biochemistry". Perspectives in Science. 6: 84–93. Bibcode:2015PerSc...6...84O. doi:10.1016/j.pisc.2015.07.002.

- ^ Ponce-Toledo, Rafael I.; López-García, Purificación; Moreira, David (October 2019). "Horizontal and endosymbiotic gene transfer in early plastid evolution". New Phytologist. 224 (2): 618–624. Bibcode:2019NewPh.224..618P. doi:10.1111/nph.15965. ISSN 0028-646X. PMC 6759420. PMID 31135958.

- ^ Ponce-Toledo, Rafael I; Moreira, David; López-García, Purificación; Deschamps, Philippe (19 June 2018). "Secondary Plastids of Euglenids and Chlorarachniophytes Function with a Mix of Genes of Red and Green Algal Ancestry". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 35 (9): 2198–2204. doi:10.1093/molbev/msy121. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 6949139. PMID 29924337.

- ^ Janson, Sven; Graneli, Edna (September 2003). "Genetic analysis of the psbA gene from single cells indicates a cryptomonad origin of the plastid in Dinophysis (Dinophyceae)". Phycologia. 42 (5): 473–477. Bibcode:2003Phyco..42..473J. doi:10.2216/i0031-8884-42-5-473.1. ISSN 0031-8884. S2CID 86730888.

- ^ Wegener Parfrey, Laura; Barbero, Erika; Lasser, Elyse; Dunthorn, Micah; Bhattacharya, Debashish; Patterson, David J.; Katz, Laura A (December 2006). "Evaluating Support for the Current Classification of Eukaryotic Diversity". PLOS Genetics. 2 (12): e220. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020220. PMC 1713255. PMID 17194223.

- ^ Burki, F.; Shalchian-Tabrizi, K.; Minge, M.; Skjæveland, Å.; Nikolaev, S. I.; et al. (2007). Butler, Geraldine (ed.). "Phylogenomics Reshuffles the Eukaryotic Supergroups". PLOS ONE. 2 (8): e790. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..790B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000790. PMC 1949142. PMID 17726520.

- ^ Moore RB; Oborník M; Janouskovec J; Chrudimský T; Vancová M; Green DH; Wright SW; Davies NW; et al. (February 2008). "A photosynthetic alveolate closely related to apicomplexan parasites". Nature. 451 (7181): 959–963. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..959M. doi:10.1038/nature06635. PMID 18288187. S2CID 28005870.

- ^ Janouškovec, J.; Tikhonenkov, D.V.; Burki, F.; Howe, A.T.; Kolísko, M.; Mylnikov, A.P.; Keeling, P.J. (2015). "Factors mediating plastid dependency and the origins of parasitism in apicomplexans and their close relatives". PNAS. 112 (33): 10200–10207. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11210200J. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423790112. PMC 4547307. PMID 25717057.

- ^ Linnæus, Caroli (1753). Species Plantarum. Vol. 2. Impensis Laurentii Salvii. p. 1131.

- ^ Sharma, O. P. (1 January 1986). Textbook of Algae. Tata McGraw-Hill. p. 22. ISBN 9780074519288.

- ^ Gmelin, S. G. (1768). Historia Fucorum. St. Petersburg: Ex typographia Academiae scientiarum – via Google Books.

- ^ Silva, P. C.; Basson, P. W.; Moe, R. L. (1996). Catalogue of the Benthic Marine Algae of the Indian Ocean. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520915817 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Medlin, Linda K.; Kooistra, Wiebe H. C. F.; Potter, Daniel; Saunders, Gary W.; Anderson, Robert A. (1997). "Phylogenetic relationships of the 'golden algae' (haptophytes, heterokont chromophytes) and their plastids" (PDF). Plant Systematics and Evolution: 188. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2013.

- ^ Dixon, P. S. (1973). Biology of the Rhodophyta. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-05-002485-0.

- ^ Harvey, D. (1836). "Algae" (PDF). In Mackay, J. T. (ed.). Flora hibernica comprising the Flowering Plants Ferns Characeae Musci Hepaticae Lichenes and Algae of Ireland arranged according to the natural system with a synopsis of the genera according to the Linnaean system. pp. 157–254. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2017..

- ^ Braun, A. Algarum unicellularium genera nova et minus cognita, praemissis observationibus de algis unicellularibus in genere (New and less known genera of unicellular algae, preceded by observations respecting unicellular algae in general) Archived 20 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Lipsiae, Apud W. Engelmann, 1855. Translation at: Lankester, E. & Busk, G. (eds.). Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, 1857, vol. 5, (17), 13–16 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine; (18), 90–96 Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine; (19), 143–149 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Siebold, C. Th. v. "Ueber einzellige Pflanzen und Thiere (On unicellular plants and animals) Archived 26 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine". In: Siebold, C. Th. v. & Kölliker, A. (1849). Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche Zoologie, Bd. 1, p. 270. Translation at: Lankester, E. & Busk, G. (eds.). Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, 1853, vol. 1, (2), 111–121 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine; (3), 195–206 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Ragan, Mark (3 June 2010). "On the delineation and higher-level classification of algae". European Journal of Phycology. 33 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/09670269810001736483. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ de Jussieu, Antoine Laurent (1789). Genera plantarum secundum ordines naturales disposita. Parisiis, Apud Viduam Herissant et Theophilum Barrois. p. 6.

- ^ Khan, Amna Komal; Kausar, Humera; Jaferi, Syyada Samra; et al. (6 November 2020). "An Insight into the Algal Evolution and Genomics". Biomolecules. 10 (11): 1524. doi:10.3390/biom10111524. PMC 7694994. PMID 33172219.

- ^ "Compte rendu du premier colloque de l'association des Diatomistes de Langue Française. Paris, 25 janvier 1980". Cryptogamie. Algologie. 1 (1): 67–74. 1980. Bibcode:1980CrypA...1...67.. doi:10.5962/p.308988. ISSN 0181-1568.

- ^ Corliss, J O (1995). "The ambiregnal protists and the codes of nomenclature: a brief review of the problem and of proposed solutions". The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 52: 11–17. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.6717. ISSN 0007-5167.

- ^ Williams, B. A.; Keeling, P. J. (2003). "Cryptic organelles in parasitic protists and fungi". In Littlewood, D. T. J. (ed.). The Evolution of Parasitism. London: Elsevier Academic Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-12-031754-7.

- ^ Round (1981). pp. 398–400, Round, F. E. (8 March 1984). The Ecology of Algae. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521269063. Retrieved 6 February 2015..

- ^ Grabda, Jadwiga; Grabda, Jadwiga (1991). Marine fish parasitology: an outline. Weinheim: VCH-Verl.-Ges. ISBN 978-0-89573-823-3.

- ^ Smith, David Roy; Keeling, Patrick J. (8 September 2016). "Protists and the Wild, Wild West of Gene Expression: New Frontiers, Lawlessness, and Misfits". Annual Review of Microbiology. 70 (1): 161–178. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095448. ISSN 0066-4227. PMID 27359218.

- ^ Schirrmeister BE, de Vos JM, Antonelli A, Bagheri HC (January 2013). "Evolution of multicellularity coincided with increased diversification of cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (5): 1791–1796. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1791S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209927110. PMC 3562814. PMID 23319632.

- ^ Baumgartner, Raphael J.; Van Kranendonk, Martin J.; Wacey, David; Fiorentini, Marco L.; Saunders, Martin; Caruso, Stefano; Pages, Anais; Homann, Martin; Guagliardo, Paul (November 2019). "Nano−porous pyrite and organic matter in 3.5-billion-year-old stromatolites record primordial life". Geology. 47 (11): 1039–1043. Bibcode:2019Geo....47.1039B. doi:10.1130/G46365.1.

- ^ a b c Reyes-Prieto, Adrian; Weber, Andreas P.M.; Bhattacharya, Debashish (2007). "The Origin and Establishment of the Plastid in Algae and Plants". Annual Review of Genetics. 41: 147–168. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130134. PMID 17600460. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ a b Khan, Amna Komal; Kausar, Humera; Jaferi, Syyada Samra; Drouet, Samantha; Hano, Christophe; Abbasi, Bilal Haider; Anjum, Sumaira (6 November 2020). "An Insight into the Algal Evolution and Genomics". Biomolecules. 10 (11): 1524. doi:10.3390/biom10111524. PMC 7694994. PMID 33172219.

- ^ Butterfield, N. J. (2000). "Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n. sp.: Implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes". Paleobiology. 26 (3): 386–404. Bibcode:2000Pbio...26..386B. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0386:BPNGNS>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0094-8373. S2CID 36648568. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007.

- ^ T.M. Gibson (2018). "Precise age of Bangiomorpha pubescens dates the origin of eukaryotic photosynthesis". Geology. 46 (2): 135–138. Bibcode:2018Geo....46..135G. doi:10.1130/G39829.1.

- ^ a b Pietluch, Filip; Mackiewicz, Paweł; Ludwig, Kacper; Gagat, Przemysław (3 September 2024). "A New Model and Dating for the Evolution of Complex Plastids of Red Alga Origin". Genome Biology and Evolution. 16 (9: evae192) evae192. doi:10.1093/gbe/evae192. PMC 11413572. PMID 39240751.

- ^ a b Strassert, Jürgen F. H.; Irisarri, Iker; Williams, Tom A.; Burki, Fabien (25 March 2021). "A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids" (PDF). Nature Communications. 12 (1): 1879. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.1879S. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22044-z. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7994803. PMID 33767194. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Keeling, Patrick J. (2017). "Chlorarachniophytes". In Archibald, John M.; Simpson, Alastair G.B.; Slamovits, Claudio H. (eds.). Handbook of the Protists. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 765–781. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28149-0_34. ISBN 978-3-319-28147-6.

- ^ Bicudo, Carlos E. de M.; Menezes, Mariângela (16 March 2016). "Phylogeny and Classification of Euglenophyceae: A Brief Review". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4: 17. Bibcode:2016FrEEv...4...17B. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00017. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ Eliáš, Marek (2021). "Protist diversity: Novel groups enrich the algal tree of life". Current Biology. 31 (11): R733 – R735. Bibcode:2021CBio...31.R733E. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.04.025. PMID 34102125. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Stiller, John W.; Schreiber, John; Yue, Jipei; Guo, Hui; Ding, Qin; Huang, Jinling (10 December 2014). "The evolution of photosynthesis in chromist algae through serial endosymbioses" (PDF). Nature Communications. 5 (1): 5764. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.5764S. doi:10.1038/ncomms6764. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4284659. PMID 25493338. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Bodył, Andrzej; Stiller, John W.; Mackiewicz, Paweł (2009). "Chromalveolate plastids: direct descent or multiple endosymbioses?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 24 (3): 119–121. Bibcode:2009TEcoE..24..119B. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.11.003. PMID 19200617. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Noble, Ivan (18 September 2003). "When plants conquered land". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 November 2006.

- ^ Wellman, C. H.; Osterloff, P. L.; Mohiuddin, U. (2003). "Fragments of the earliest land plants". Nature. 425 (6955): 282–285. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..282W. doi:10.1038/nature01884. PMID 13679913. S2CID 4383813. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017.

- ^ Kenrick, P.; Crane, P.R. (1997). The origin and early diversification of land plants. A cladistic study. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-729-1.

- ^ Raven, J.A.; Edwards, D. (2001). "Roots: evolutionary origins and biogeochemical significance". Journal of Experimental Botany. 52 (90001): 381–401. doi:10.1093/jexbot/52.suppl_1.381. PMID 11326045.

- ^ Knauth, L. Paul; Kennedy, Martin J. (2009). "The late Precambrian greening of the Earth". Nature. 460 (7256): 728–732. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..728K. doi:10.1038/nature08213. PMID 19587681. S2CID 4398942.

- ^ Strother, Paul K.; Battison, Leila; Brasier, Martin D.; Wellman, Charles H. (2011). "Earth's earliest non-marine eukaryotes". Nature. 473 (7348): 505–509. Bibcode:2011Natur.473..505S. doi:10.1038/nature09943. PMID 21490597. S2CID 4418860.

- ^ a b c d Round, F. E. (1981). "Chapter 8, Dispersal, continuity and phytogeography". The ecology of algae. CUP Archive. pp. 357–361. ISBN 9780521269063 – via Google Books.

- ^ Round (1981), p. 362.

- ^ Round (1981), p. 357.

- ^ Round (1981), p. 371.

- ^ Round (1981), p. 366.

- ^ "Algae Herbarium". National Museum of Natural History, Department of Botany. 2008. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- ^ John (2002), p. 1.

- ^ Huisman (2000), p. 25.

- ^ Stegenga (1997).

- ^ Clerck, Olivier (2005). Guide to the seaweeds of KwaZulu-Natal. National Botanic Garden of Belgium. ISBN 978-90-72619-64-8.

- ^ Abbott and Hollenberg (1976), p. 2.

- ^ Hardy and Guiry (2006).

- ^ Round (1981), p. 176.

- ^ "Greenland Has a Mysterious 'Dark Zone' — And It's Getting Even Darker". Space.com. 10 April 2018.

- ^ "Alpine glacier turning pink due to algae that accelerates climate change, scientists say". Sky News. 6 July 2020.

- ^ Smayda, Theodore J. (2014). "What is a bloom? A commentary". Limnology and Oceanography. 42 (5part2): 1132–1136. doi:10.4319/lo.1997.42.5_part_2.1132. ISSN 0024-3590.

- ^ a b c Omar, Wan Maznah Wan (December 2010). "Perspectives on the Use of Algae as Biological Indicators for Monitoring and Protecting Aquatic Environments, with Special Reference to Malaysian Freshwater Ecosystems". Trop Life Sci Res. 21 (2): 51–67. PMC 3819078. PMID 24575199.

- ^ Necchi Jr., O. (ed.) (2016). River Algae. Springer, Necchi, Orlando J. R. (2 June 2016). River Algae. Springer. ISBN 9783319319841..

- ^ Johansen, J. R. (2012). "The Diatoms: Applications for the Environmental and Earth Sciences". In Smol, J. P.; Stoermer, E. F. (eds.). Diatoms of aerial habitats (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 465–472. ISBN 9781139492621 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sharma, O. P. (1986). pp. 2–6, [1].

- ^ Brodo, Irwin M.; Sharnoff, Sylvia Duran; Sharnoff, Stephen; Laurie-Bourque, Susan (2001). Lichens of North America. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-300-08249-4.

- ^ Pearson, Lorentz C. (1995). The Diversity and Evolution of Plants. CRC Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-8493-2483-3.

- ^ Tuovinen, Veera; Ekman, Stefan; Thor, Göran; Vanderpool, Dan; Spribille, Toby; Johannesson, Hanna (17 January 2019). "Two Basidiomycete Fungi in the Cortex of Wolf Lichens". Current Biology. 29 (3): 476–483.e5. Bibcode:2019CBio...29E.476T. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.12.022. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 30661799.

- ^ Brodo et al. (2001), p. 6: "A species of lichen collected anywhere in its range has the same lichen-forming fungus and, generally, the same photobiont. (A particular photobiont, though, may associate with scores of different lichen fungi)."

- ^ Brodo et al. (2001), p. 8.

- ^ Taylor, Dennis L. (1983). "The coral-algal symbiosis". In Goff, Lynda J. (ed.). Algal Symbiosis: A Continuum of Interaction Strategies. CUP Archive. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-521-25541-7.

- ^ Knight, Susan (Fall 2001). "Are There Sponges in Your Lake?" (PDF). Lake Tides. 26 (4). Wisconsin Lakes Partnership: 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2007 – via UWSP.edu.

- ^ Huesemann, M.; Williams, P.; Edmundson, Scott J.; Chen, P.; Kruk, R.; Cullinan, V.; Crowe, B.; Lundquist, T. (September 2017). "The laboratory environmental algae pond simulator (LEAPS) photobioreactor: Validation using outdoor pond cultures of Chlorella sorokiniana and Nannochloropsis salina". Algal Research. 26: 39–46. Bibcode:2017AlgRe..26...39H. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2017.06.017. ISSN 2211-9264. OSTI 1581797.

- ^ "Seaweed Aquaculture | California Sea Grant". caseagrant.ucsd.edu. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Lane, Katie; Derbyshire, Emma; Li, Weili; Brennan, Charles (January 2014). "Bioavailability and Potential Uses of Vegetarian Sources of Omega-3 Fatty Acids: A Review of the Literature". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 54 (5): 572–579. doi:10.1080/10408398.2011.596292. PMID 24261532. S2CID 30307483.

- ^ Winwood, R.J. (2013). "Algal oil as a source of omega-3 fatty acids". Food Enrichment with Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition. pp. 389–404. doi:10.1533/9780857098863.4.389. ISBN 978-0-85709-428-5.

- ^ Lenihan-Geels, Georgia; Bishop, Karen; Ferguson, Lynnette (18 April 2013). "Alternative Sources of Omega-3 Fats: Can We Find a Sustainable Substitute for Fish?". Nutrients. 5 (4): 1301–1315. doi:10.3390/nu5041301. PMC 3705349. PMID 23598439.

- ^ Venkatesh, G. (1 March 2022). "Circular Bio-economy—Paradigm for the Future: Systematic Review of Scientific Journal Publications from 2015 to 2021". Circular Economy and Sustainability. 2 (1): 231–279. Bibcode:2022CirES...2..231V. doi:10.1007/s43615-021-00084-3. ISSN 2730-5988. S2CID 238768104.

- ^ a b Diaz, Crisandra J.; Douglas, Kai J.; Kang, Kalisa; Kolarik, Ashlynn L.; Malinovski, Rodeon; Torres-Tiji, Yasin; Molino, João V.; Badary, Amr; Mayfield, Stephen P. (2023). "Developing algae as a sustainable food source". Frontiers in Nutrition. 9. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.1029841. ISSN 2296-861X. PMC 9892066. PMID 36742010.

- ^ a b The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024. FAO. 7 June 2024. doi:10.4060/cd0683en. ISBN 978-92-5-138763-4.

- ^ In brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018 (PDF). FAO. 2018.

- ^ Verdelho Vieira, Vítor; Cadoret, Jean-Paul; Acien, F. Gabriel; Benemann, John (January 2022). "Clarification of Most Relevant Concepts Related to the Microalgae Production Sector". Processes. 10 (1): 175. doi:10.3390/pr10010175. hdl:10835/13146. ISSN 2227-9717.

- ^ Greene, Charles; Scott-Buechler, Celina; Hausner, Arjun; Johnson, Zackary; Lei, Xin Gen; Huntley, Mark (2022). "Transforming the Future of Marine Aquaculture: A Circular Economy Approach". Oceanography: 26–34. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2022.213. ISSN 1042-8275.

- News article about the study: "Nutrient-rich algae could help meet global food demand: Cornell researchers". CTVNews. 20 October 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Daman; Caminiti, Jeff; Edmundson, Scott; Gao, Song; Wick, Macdonald; Huesemann, Michael (12 July 2022). "Seaweed proteins are nutritionally valuable components in the human diet". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 116 (4): 855–861. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqac190. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 35820048.

- ^ "Seaweeds: Plants or Algae?". Point Reyes National Seashore Association. Retrieved 1 December 2018.