Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

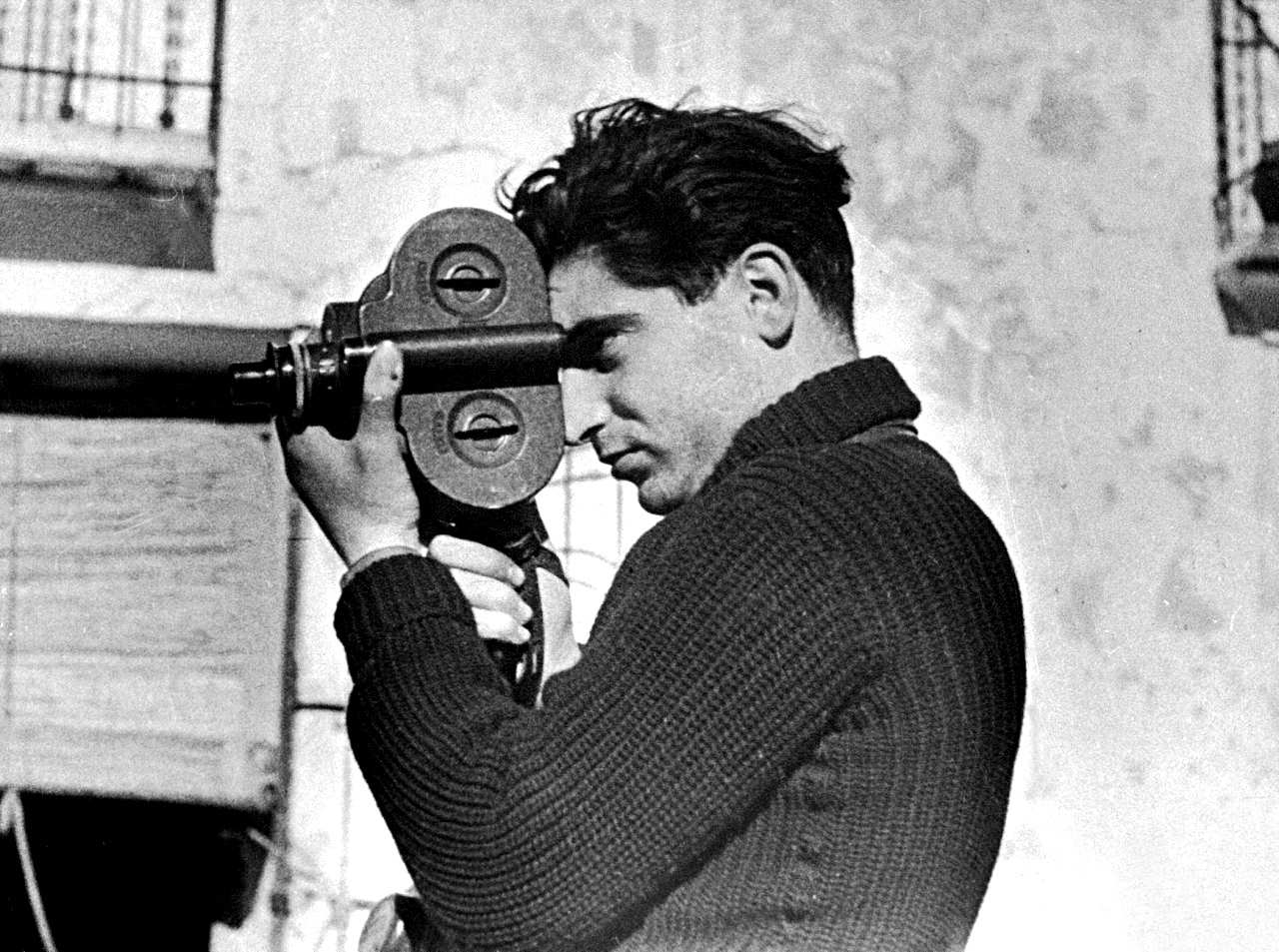

Robert Capa

View on Wikipedia

Robert Capa (/ˈkɑːpə/; born Endre Ernő Friedmann,[1] Hungarian: [ˈɛndrɛ ˈɛrnøː ˈfridmɒn]; October 22, 1913 – May 25, 1954) was a Hungarian-American war photographer and photojournalist. He is considered by some to be the greatest combat and adventure photographer in history.[2]

Key Information

Friedman had fled political repression in Hungary when he was a teenager, moving to Berlin, where he enrolled in college. He witnessed Adolf Hitler's rise to power, which led him to move to Paris, where he met and began to work with his professional partner Gerda Taro, and they began to publish their work separately. Capa's close friendship with David Seymour-Chim was captured in Martha Gellhorn's novella Two by Two. He subsequently covered five wars: the Spanish Civil War, the Second Sino-Japanese War, World War II across Europe, the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and the First Indochina War, with his photos published in major magazines and newspapers.[3]

During his career he risked his life numerous times, most dramatically as the only civilian photographer landing on Omaha Beach on D-Day. He documented the course of World War II in London, North Africa, Italy, and the liberation of Paris. His friends and colleagues included Ernest Hemingway, Irwin Shaw, John Steinbeck and director John Huston.

In 1947, for his work recording World War II in pictures, U.S. general Dwight D. Eisenhower awarded Capa the Medal of Freedom. That same year, Capa co-founded Magnum Photos in Paris. The organization was the first cooperative agency for worldwide freelance photographers. Hungary has issued a stamp and a gold coin in his honor.

He was killed when he stepped on a landmine in Vietnam.

Early years

[edit]Capa was born Endre Ernő Friedmann to the Jewish family of Júlia (née Berkovits) and Dezső Friedmann in Budapest, Austria-Hungary, on October 22, 1913.[2] His mother, Julianna Henrietta Berkovits was a native of Nagykapos (now Veľké Kapušany, Slovakia) and Dezső Friedmann came from the Transylvanian village of Csucsa (now Ciucea, Romania).[2] At the age of 18, he was accused of alleged communist sympathies and was forced to flee Hungary.[4]: 154

He moved to Berlin, where he enrolled at Berlin University where he worked part-time as a darkroom assistant for income and then became a staff photographer for the German photographic agency, Dephot.[4]: 154 It was during that period that the Nazi Party came into power, which made Capa, a Jew, decide to leave Germany and move to Paris.[4]: 154

Career

[edit]Capa's first published photograph was of Leon Trotsky making a speech in Copenhagen on "The Meaning of the Russian Revolution" in 1932.[5]

After moving to Paris, he became professionally involved with Gerta Pohorylle, later known as Gerda Taro,[6] a German-Jewish photographer who had moved to Paris for the same reasons he did.[4]: 154 The two of them decided to work under the alias Capa at this time, and she contributed to much of the early work. However, the two of them later separated aliases, with Pohorylle quickly creating her own alias 'Gerda Taro', and began publishing their work independently. Capa and Taro developed a romantic relationship alongside their professional one. Capa proposed and Taro refused, but they continued their involvement. He also shared a darkroom with French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, with whom he would later co-found the Magnum Photos cooperative.[4]: 154 [7]

Spanish Civil War, 1936

[edit]

From 1936 to 1939, Capa worked in Spain, photographing the Spanish Civil War, along with Taro and David Seymour.[8]

It was during that war that Capa took the photo now called The Falling Soldier (1936), purported to show the death of a Republican soldier. The photo was published in magazines in France and then by Life and Picture Post.[9] The authenticity of the photo was later questioned, with evidence including other photos from the scene suggesting it was staged.[a] Picture Post, a pioneering photojournalism magazine published in the United Kingdom, had once described then twenty-five year old Capa as "the greatest war photographer in the world."[4]: 155

The next year, in 1937, Taro died when the motor vehicle on which she was traveling (apparently standing on the footboard) collided with an out-of-control tank. She had been returning from a photographic assignment covering the Battle of Brunete.[4]

Capa accompanied then-journalist and author Ernest Hemingway to photograph the war, which Hemingway later described in his novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940).[12] Life magazine published an article about Hemingway and his time in Spain, along with numerous photos by Capa.[13]

In December 2007, three boxes filled with rolls of film, containing 4,500 35mm negatives of the Spanish Civil War by Capa, Taro, and Chim (David Seymour), which had been considered lost since 1939, were discovered in Mexico.[14][15][16][17][18] In 2011, Trisha Ziff directed a film about those images, entitled The Mexican Suitcase.[19]

All you could do was to help individuals caught up in war, try to raise their spirits for a moment, perhaps flirt a little, make them laugh; ... and you could photograph them, to let them know that somebody cared.

Chinese resistance to Imperial Japan, 1938

[edit]In 1938, he traveled to the Chinese city of Hankou, now within Wuhan, to document the resistance to the Japanese invasion.[21] He sent his images to Life magazine, which published some of them in its May 23, 1938, issue.[22]

World War II

[edit]At the start of World War II, Capa was in New York City, having moved there from Paris to look for work, and to escape Nazi persecution. During the war, Capa was sent to various parts of the European Theatre on photography assignments.[23] He first photographed for Collier's Weekly, before switching to Life after he was fired by Collier's. He was the only "enemy alien" photographer for the Allies.[24] On October 7, 1943, Robert Capa was in Naples with Life reporter Will Lang Jr., and there he photographed the Naples post office bombing.[25]

D-Day, Omaha beach, 1944

[edit]A group of images known as "The Magnificent Eleven" were taken by Capa on D-Day.[26] Taking part in the Allied invasion, Capa was attached to the 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division ("Big Red One") on Omaha Beach.[27][7][28] The US personnel attacking Omaha Beach faced some of the heaviest resistance from German troops inside the bunkers of the Atlantic Wall. Photographic historian A. D. Coleman has suggested that Capa traveled to the beach in the same landing craft as Colonel George A. Taylor, commander of the 16th Infantry Regiment, who landed 1½ hours after the first wave, near Colleville-sur-Mer.[29]

Capa subsequently stated that he took 106 pictures, but later discovered that all but 11 had been destroyed. This incident may have been caused by Capa's cameras becoming waterlogged at Normandy,[7] although the more frequent allegation is that a young assistant accidentally destroyed the pictures while they were being developed at the photo lab in London.[30] However, this narrative has been challenged by Coleman and others.[29] In 2016, John G. Morris, who was picture editor at the London bureau of Life in 1944, agreed that it was more likely that Capa captured 11 images in total on D-Day.[29][31] The 11 prints were included in Life magazine's issue on June 19, 1944,[32] with captions written by magazine staffers, as Capa did not provide Life with notes or a verbal description of what they showed.[29]

The captions have since been shown to be erroneous, as were subsequent descriptions of the images by Capa himself.[29] For example, men described by Life as infantrymen taking cover behind a hedgehog obstacle during the assault landing were in fact members of Gap Assault Team 10 – a combined US Navy/US Army demolition unit tasked with blowing up obstacles and clearing the way for landing craft after the beach had been secured.[29][33]

The Shaved Woman of Chartres

[edit]Capa took photographs during the Allied invasion of France in 1944. His picture The Shaved Woman of Chartres, taken on August 16, 1944, shows a woman whose head has been shaved as a punishment for collaboration with the Nazis.[34]

On April 18, 1945, Capa captured images of a fight to secure a bridge in Leipzig, Germany. These pictures included an image of Raymond J. Bowman's death by sniper fire. This image was published in a spread in Life magazine with the caption "The picture of the last man to die."[35]

Post-war Soviet Union, 1947

[edit]In 1947 Capa traveled to the Soviet Union with his friend, the American writer John Steinbeck.[36] They originally met when they shared a room in an Algiers hotel with other war correspondents before the Allied invasion of Italy in 1943.[36] They reconnected in New York, where Steinbeck told him he was thinking about visiting the Soviet Union, now that the war was over.[36]

Capa suggested they go there together and collaborate on a book, with Capa documenting the war-torn nation with photographs.[37] The trip resulted in Steinbeck's A Russian Journal, which was published both as a book and a syndicated newspaper serial.[36] Photos were taken in Moscow, Kyiv, Tbilisi, Batumi and among the ruins of Stalingrad.[36][38][39][40] They remained good friends until Capa's death; Steinbeck took the news of Capa's death very hard.[36][41]

Magnum Photos agency, 1947

[edit]In 1947, Capa founded the cooperative venture Magnum Photos in Paris with Henri Cartier-Bresson, William Vandivert, David Seymour, and George Rodger. It was a cooperative agency to manage work for and by freelance photographers, and developed a reputation for the excellence of its photo-journalists. In 1952, he became the president.[citation needed]

Founding of Israel, 1948

[edit]Capa toured Israel during its founding and while it was being attacked by neighboring states. He took the numerous photographs that accompanied Irwin Shaw's book, Report on Israel.[42]

Documenting film productions, 1953

[edit]In 1953 he joined screenwriter Truman Capote and director John Huston in Italy where Capa was assigned to photograph the making of the film, Beat the Devil.[43] During their off time they, and star Humphrey Bogart, enjoyed playing poker.[44][45]

Capa also acted in the film Temptation (1946 film), playing a supporting role. Allegedly, Capa received the part after visiting his friend Charles Korvin on the set. Capa claimed that he could play the part better than the actor who had originally been cast, and after speaking with the director was cast in the final film.

First Indochina War and death, 1954

[edit]In the early 1950s, Capa travelled to Japan for an exhibition associated with Magnum Photos. While there, Life magazine asked him to go on assignment to Southeast Asia, where the French had been fighting for eight years in the First Indochina War. Although he had claimed a few years earlier that he was finished with war, Capa accepted the job. He accompanied a French regiment located in Thái Bình Province with two Time-Life journalists, John Mecklin and Jim Lucas. On May 25, 1954, the regiment was passing through a dangerous area under fire when Capa decided to leave his jeep and go up the road to photograph the advance. Capa was killed when he stepped on a landmine near the road.[46][4]: 155 [47]

Personal life

[edit]Capa was born into a middle-class Jewish family in Budapest,[48] where his parents were tailors. Capa's mother was a successful fashion shop owner, and his father was a tailor in her shop.[49] Capa had two brothers: a younger brother, photographer Cornell Capa and an older brother, László Friedmann.

At the age of 18, Capa moved to Vienna, later relocated to Prague, and finally settled in Berlin: all cities that were centers of artistic and cultural ferment in this period. He studied at the Deutsche Hochschule für Politik from 1931 until 1933, when the Nazi Party instituted restrictions on Jews and banned them from universities.[50] He then moved to Paris and in 1934 met Gerda Pohorylle, a German Jewish refugee. "André Friedman", as he called himself then, taught Gerda photography, and together they created the name and image of "Robert Capa". At that time, both photographers published their work under the pseudonym of Robert Capa.[51] Gerda later took the name Gerda Taro and became successful in her own right. She travelled with Capa to Spain in 1936 intending to document the Spanish Civil War. In July 1937, Capa traveled briefly to Paris while Gerda remained in Madrid. She was killed near Brunete during a battle.[52][53] Capa, who was reportedly engaged to her, was deeply shocked and never married.

In February 1943, Capa met Elaine Justin. They fell in love and the relationship lasted until the end of the war. Capa spent most of his time on the front line. Capa called the redheaded Elaine "Pinky," and wrote about her in his war memoir, Slightly Out of Focus. In 1945, Elaine Justin broke up with Capa; she later married Chuck Romine. Some months later, Capa became the lover of the actress Ingrid Bergman, who was touring in Europe to entertain American soldiers.[54]p. 176 In December 1945, Capa followed her to Hollywood. The relationship ended in the summer of 1946 when Capa traveled to Turkey.[7]

Legacy

[edit]

The government of Hungary issued a postage stamp in Capa's honor in 2013.[55] That same year it issued a 5,000-forint ($20) gold coin, also in his honor, showing an engraving of Capa.[56]

His younger brother, Cornell Capa, also a photographer, worked to preserve and promote Robert's legacy as well as develop his own identity and style. He founded the International Fund for Concerned Photography in 1966. To give this collection a permanent home, he founded the International Center of Photography in New York City in 1974. This was one of the foremost and most extensive conservation efforts on photography to be developed. Indeed, Capa and his brother believed strongly in the importance of photography and its preservation, much like film would later be perceived and duly treated in a similar way. The Overseas Press Club created the Robert Capa Gold Medal in the photographer's honor.[57]

Capa is known for redefining wartime photojournalism. His work came from the trenches as opposed to the more arms-length perspective that was the precedent. He was famed for saying, "If your photographs aren't good enough, you're not close enough."[58]

He is credited with coining the term Generation X. He used it as a title for a photo-essay about the young people reaching adulthood immediately after the Second World War. It was published in 1953 in Picture Post (UK) and Holiday (US). Capa said, "We named this unknown generation, The Generation X, and even in our first enthusiasm we realised that we had something far bigger than our talents and pockets could cope with."[59]

In 1947, for his work recording World War II in pictures, U.S. general Dwight D. Eisenhower awarded Capa the Medal of Freedom Citation[7][20] The International Center of Photography organized a travelling exhibition titled This Is War: Robert Capa at Work, which displayed Capa's innovations as a photojournalist in the 1930s and 1940s. It includes vintage prints, contact sheets, caption sheets, handwritten observations, personal letters and original magazine layouts from the Spanish Civil War, the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II. The exhibition appeared at the Barbican Art Gallery, the International Center of Photography of Milan, and the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya in the fall of 2009, before moving to the Nederlands Fotomuseum from October 10, 2009, until January 10, 2010.[60]

In 1976 Capa was posthumously inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.[61]

Politics

[edit]As a young boy, Capa was drawn to the Munkakör (Employment Circle), a group of socialist and avant-garde artists, photographers, and intellectuals centered around Budapest. He participated in the demonstrations against the Miklós Horthy regime. In 1931, just before his first photo was published, Capa was arrested by the Hungarian secret police, beaten, and jailed for his radical political activity. A police official's wife—who happened to know his family—won Capa's release on the condition that he would leave Hungary immediately.[5]

The Boston Review has described Capa as "a leftist, and a democrat—he was passionately pro-Loyalist and passionately anti-fascist ..." During the Spanish Civil War, Capa travelled with and photographed the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), which resulted in his best-known photograph.[5]

The British magazine Picture Post ran his photos from Spain in the 1930s accompanied by a portrait of Capa, in profile, with the simple description: "He is a passionate democrat, and he lives to take photographs."[5]

Artistic style

[edit]Robert Capa's photographic style is characterized by his commitment to capturing the raw and immediate realities of war. He famously stated, "If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough," reflecting his philosophy of immersing himself in the action to convey authenticity.[62][63]

In popular culture

[edit]- In 2013, the Japanese Female Musical Theater group Takarazuka Revue produced a musical piece based on the life of Capa. Ms. Ouki Kaname performed the lead role as Capa. The group performed the musical in 2012 in Takarazuka and Tokyo and in 2014 in Nagoya.

- In Patrick Modiano's novella Afterimage Capa is a mentor for the subject of the novella, Francis Jansen, a photographer who retires to Mexico.

- In Alfred Hitchcock's movie Rear Window, the protagonist L. B. "Jeff" Jefferies (James Stewart) was partly based on Capa.[64]

- Poet Owen Sheers wrote a poem about Capa, named Happy Accidents. It can be found in the anthology Skirrid Hill.

- In English indie rock group Alt-J's 2012 album An Awesome Wave, the love between Capa and Taro, and the circumstances of his death are described in the second-to-last track, "Taro".

- The Austrian rock singer Falco wrote the song "Kamikaze Cappa" in tribute to Capa.[65]

Collections

[edit]- Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois[66]

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York[67]

- Museum of Modern Art, New York[68]

- Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center, Budapest

- Robert Capa: The Definitive Collection, Magnum Photos[69]

- Robert Capa, International Center of Photography[70]

- Robert Capa Photographs, Worcester Art Museum[71]

- Robert Capa, The J. Paul Getty Museum[72]

- Robert Capa, International Photography Hall of Fame[61]

Publications

[edit]Publications by Capa

[edit]- The Battle of Waterloo Road. New York: Random House, 1941. OCLC 654774055. Photographs by Capa. With text by Diana Forbes-Robertson.

- Invasion!. New York, London: D. Appleton-Century, 1944. OCLC 1022382. Photographs by Capa. With text by Charles Wertenbaker.

- Slightly Out of Focus. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1947. New York: Modern Library, 2001. ISBN 9780375753961. Text and photographs by Capa. With a foreword by Cornell Capa and an introduction by Richard Whelan. A memoir.

- Images of War. New York: Grossman, 1964. Text and photographs by Capa. OCLC 284771. With a text by John Steinbeck.

- Robert Capa: Photographs. New York: Aperture, 1996. ISBN 978-0893816759. New York: Aperture, 2004.

- Heart of Spain: Robert Capa's Photographs of the Spanish Civil War. New York: Aperture, 1999. ISBN 9780893818319. New York: Aperture, 2005. ISBN 978-1931788021.

- Robert Capa: The Definitive Collection. London, New York: Phaidon, 2001. ISBN 9780714840673. London, New York: Phaidon, 2004. ISBN 978-0714844497. Edited by Richard Whelan.

- Robert Capa at Work: This is War!. Göttingen: Steidl, 2009. ISBN 9783865219442. Photographs by Capa. With a foreword by Willis E. Hartshorn, an introduction by Christopher Phillips, and text by Richard Whelan. Published to accompany an exhibition at the International Center of Photography, New York, September 2007 – January 2008. "A detailed examination of six of Robert Capa's most important war reportages from the first half of his career: the Falling Soldier (1936), Chinese resistance to the Japanese invasion (1938), the end of the Spanish Civil War in Catalonia (1938–39), D-Day, the US paratroop invasion of Germany and the liberation of Leipzig (1945)."[73]

- Questa è la Guerra!: Robert Capa al Lavoro. Italy: Contrasto, 2009. ISBN 9788869651601. Published to accompany an exhibition in Milan, March–June 2009.[74]

Publications with others

[edit]- Death in the Making. New York: Covici Friede, 1938. Photographs by Capa and Taro.

- A Russian Journal. New York: Viking, 1948. Text by John Steinbeck, illustrated with photographs by Capa.

- Report on Israel. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1950. By Irwin Shaw and Capa.

Publications about Capa

[edit]- Robert Capa: a Biography. New York: Knopf, 1985. By Richard Whelan. ISBN 0-394-52488-8.

- Blood and Champagne: The Life and Times of Robert Capa. Macmillan, 2002; Thomas Dunne, 2003; ISBN 978-0312315641. Da Capo Press, 2004; ISBN 978-0306813566. By Alex Kershaw.

- La foto de Capa. Córdoba: Paso de Cebra Ediciones, 2011. A fictionalised account of the discovery of the exact location of the "Falling Soldier" photograph. ISBN 978-84-939103-0-3.

- Nizza oder die Liebe zur Kunst. Bad König: Vantage Point World, 2013. By Axel Dielmann. ISBN 978-3-981-53549-5. Text in German.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Capa, Robert". Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ a b c Kershaw, Alex. Blood and Champagne: The Life and Times of Robert Capa, Macmillan (2002) ISBN 978-0306813566

- ^ Hudson, Berkley (2009). Sterling, Christopher H. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Journalism. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE. pp. 1060–67. ISBN 978-0-7619-2957-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Davenport, Alma. The History of Photography: An Overview, Univ. of New Mexico Press (1991)

- ^ a b c d "Linfield, Boston Review". Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "Photo of Gerda Taro". zakhor-online.com. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Robert Capa’s Longest Day", Vanity Fair, June 2014

- ^ "New Works by Photography’s Old Masters", New York Times, April 30, 2009

- ^ Ingledew, John. Photography, Laurence King Publishing (2005) p. 184

- ^ "Richard Whelan, Proving that Robert Capa's Falling Soldier is Genuine: a Detective Story, American Masters, PBS Website". PBS. Archived from the original on August 12, 2006. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ "Iconic Capa war photo was stage: newspaper" Archived July 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, AFP

- ^ "Photo of Capa (far left) with Hemingway (far right) in Spain". wordpress.com. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "Life Documents Hemingway's New Novel with War Shots", Life magazine, January 6, 1941

- ^ The212BERLIN (August 4, 2011). "The Mexican Suitcase trailer". Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2018 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Capa Cache", New York Times, January 27, 2008

- ^ "The Mexican Suitcase, Rediscovered Spanish Civil War Negatives by Capa, Chim, and Taro" Archived February 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, International Center of Photography

- ^ "Photo of the Spanish Civil War". icp.org. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "The Fascinating Story of The Mexican Suitcase" Archived December 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, ORMS

- ^ "Meet the DocuWeeks Filmmakers: Trisha Ziff--'The Mexican Suitcase'". Documentary. No. August 2011. International Documentary Association. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ a b George Stevens Jr., "Robert Capa: A Photographer at War", Washington Post, September 29, 1985

- ^ Stephen R. MacKinnon includes photographs by Robert Capa, in Wuhan, 1938: War, Refugees, and the Making of Modern China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

- ^ Capa photos of the Chinese resistance, Life, May 23, 1938

- ^ Brenner, Marie. "War Photographer Robert Capa and his Coverage of D-day". Vanity Fair. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ "Robert Capa at 100: The war photographer's legacy". www.bbc.com. October 22, 2013. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Slightly Out of Focus, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1947, p. 104

- ^ "Photo by Capa on D-Day". pinimg.com. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ D-Day, National WWII Museum

- ^ Jay (December 2, 2012). "The Reel Foto: Robert Capa: 20th Century War Photographer". reelfoto.blogspot.com. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Coleman, A. D. (February 12, 2019). "Alternate History: Robert Capa on D-Day". exposure magazine. Society for Photographic Education. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ Simon Kuper, "Interview: John Morris on his friend Robert Capa", Financial Times, May 31, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ^ Estrin, James (December 6, 2016). "As He Turns 100, John Morris Recalls a Century in Photojournalism". Lens Blog. New York Times. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ "Life magazine story with Capa's images". slightly-out-of-focus.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ Lt. (jg) H. L. Blackwell, Jr. Report on Naval Combat Demolition Units [NCDUs] In Operation "Neptune" as part of Task Force 122 (5 July, 1944) (February 19, 2019).

- ^ Match, Paris (August 22, 2014). "2014 – L'été de la mémoire – La véritable histoire de la tondue de Chartres". parismatch.com.

- ^ "Bowman, Raymond J." tracesofwar.com. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Railsback, Brian E., Meyer, Michael J. A John Steinbeck Encyclopedia, Greenwood Publishing Group (2006) p. 50

- ^ "Photo of John Steinbeck and Robert Capa boarding a plane for the USSR, 1947". phaidon.com. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "Photo of Stalingrad, taken by Capa". Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ "Photo of Tiflis, Georgia, 1947". pinimg.com. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "Photo of Georgian farmworkers". agenda.ge. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "Photo of Capa and Steinbeck". pinimg.com. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "Robert Capa's Road to Jerusalem", Jewish Review of Books, Winter 2016

- ^ "Robert Capa Remembered", Independent UK, October 12, 1996

- ^ "Photo of Capa, John Huston and Burl Ives". pinimg.com. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "Robert Capa Photo Gallery". gettyimages.com. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ Aronson, Marc; Budhos, Marina (2017). Eyes of the World Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and the Invention of Modern Photojournalism. Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC. ISBN 9780805098358.

- ^ Badenbroek, Michael. "Robert Capa – war photographer". army-photographer.com. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- ^ "Robert Capa" Archived April 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Jewish History, Hungary

- ^ "Robert Capa". International Photography Hall of Fame.

- ^ "Robert Capa". Capa Központ. Retrieved April 6, 2025.

- ^ "Gerda Taro, Robert Capa y los peligros de firmar con un seudónimo masculino". eldiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ^ "Gerda Taro 80: Killed on Assignment | World Book". www.worldbook.com. Retrieved April 6, 2025.

- ^ O'Hagan, Sean; O’Hagan, Sean (May 12, 2012). "Robert Capa and Gerda Taro: love in a time of war". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved April 6, 2025.

- ^ Marton, Kati (2006). The Great Escape: Nine Jews Who Fled Hitler and Changed the World. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6115-9. LCCN 2006049162. OCLC 70864519.

- ^ "Magyar Posta Ltd. – 2013". Magyar Posta Zrt. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ "Photo of Hungarian gold coin dedicated to Capa". coin-currency.com. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "Overseas Press Club of America, Awards Archive". Archived from the original on November 5, 2007.

- ^ "Robert Capa". Magnum Photos. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012.

- ^ Ulrich, John (November 1, 2003). "Introduction: A (Sub)cultural Genealogy". In Andrea L. Harris (ed.). GenXegesis: Essays on Alternative Youth. Popular Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780879728625.

- ^ Travelling exhibitions: This Is War! Robert Capa at Work Archived May 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, International Center of Photography

- ^ a b "Robert Capa". International Photography Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ Cosgrove, Ben. "Robert Capa Reveals an Ugly Side of Liberation in WWII France". TIME.

- ^ "Robert Capa: The Man Who Captured War Through His Lens".

- ^ Belton, John (2000). Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window (PDF). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-521-56423-9.

- ^ "Rock Me, Falco". www.metafilter.com. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ "Robert Capa". The Art Institute of Chicago.

- ^ "Robert Capa | The Falling Soldier". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1936.

- ^ "Robert Capa. Death of a Loyalist Militiaman, Córdoba front, Spain. Late August-early September, 1936 | MoMA".

- ^ "Robert Capa: The Definitive Collection". Magnum Photos. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Robert Capa". International Center of Photography. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Robert Capa Photographs". Worcester Art Museum. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Robert Capa". The J Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ Capa, Robert; Whelan, Richard; International Center of Photography (April 1, 2018). Robert Capa at work: this is war!. Steidl ; Thames & Hudson [distributor. OCLC 755099561.

- ^ Whelan, Richard; International Center of Photography (April 1, 2018). Questa e la Guerra!: Robert Capa al lavoro. International Center of Photography : Two Contrast. OCLC 772645394.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)

External links

[edit]- Capa's Photography Portfolio — Magnum Photos

- PBS biography and analysis of Falling Soldier authenticity Archived August 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Discussion on the authenticity of Capa's "Fallen Republican Soldier" Does it matter if it was faked?

- Robert Capa's "Lost Negatives", The New York Times, 2008

- Photography Temple. "Photographer Robert Capa"

- The woman who captured Robert Capa's heart, The Independent, 2010

- Driven to Shoot on the Frontlines, The Japan Times, 2014

- Robert Capa at Find a Grave

Robert Capa

View on GrokipediaRobert Capa (born Endre Friedmann; 22 October 1913 – 25 May 1954) was a Hungarian-born war photographer and photojournalist.[1] He gained international prominence for his frontline images during the Spanish Civil War, including the debated "The Falling Soldier" photograph depicting a Loyalist militiaman at the moment of being shot.[2][3] Capa documented World War II extensively, most notably landing with U.S. troops on Omaha Beach during the D-Day invasion on 6 June 1944, where only eleven of his photographs survived due to lab mishandling.[4][1] In 1947, he co-founded Magnum Photos, a cooperative agency, with Henri Cartier-Bresson, David Seymour, George Rodger, and William Vandivert to advance photojournalism.[2] Capa died at age 40 after stepping on a landmine while covering the First Indochina War for Life magazine.[2]

Early Life

Childhood and Family in Hungary

Robert Capa was born Endre Friedmann on October 22, 1913, in Budapest, Hungary, as the second of three sons to Henrietta Julianna Berkovits and Dávid Friedmann, a master tailor by trade.[5] [6] The family was Jewish and middle-class, residing on the Pest side of the city, where his parents ran a tailoring business; his mother also operated a successful fashion shop that contributed to their modest prosperity.[7] [8] Raised in a liberal Jewish household amid the political turbulence following World War I and the establishment of the Horthy regime in 1920, Friedmann's early years were shaped by Hungary's interwar instability, including economic hardships and antisemitic undercurrents that later influenced his decision to emigrate.[7] As an adolescent, he developed an attraction to left-wing ideas, reflecting the era's ideological ferment among urban Jewish youth, though specific childhood pursuits like exploration in Budapest's streets were anecdotal and unverified in primary accounts.[7] His father's adventurous storytelling and the family's textile milieu provided a backdrop, but Friedmann showed no documented early interest in photography during this period, which emerged later in his teens.[9]Emigration to Berlin and Initial Influences

In 1931, Endre Ernő Friedmann, aged 17 or 18, emigrated from Budapest to Berlin, fleeing political repression in Hungary following his arrest by secret police for involvement in leftist student activism and protests against the regime.[10] In Berlin, he enrolled at the Deutsche Hochschule für Politik to study journalism and political science, immersing himself in the intellectual and political ferment of Weimar Germany amid economic instability and rising extremism.[11][12] Friedmann's entry into photography occurred through practical apprenticeships rather than formal training; he secured work as a darkroom assistant at the Dephot photo agency, a leftist-oriented outfit that distributed images to publications, where he processed negatives and learned technical skills under Hungarian expatriate mentors.[13][14] He collaborated informally with fellow Hungarian émigré photographer Eva Besnyö, utilizing her darkroom facilities and gaining exposure to selling work via progressive agencies, which shaped his early approach to documentary imaging as a tool for social commentary.[14] These years in Berlin profoundly influenced Friedmann's worldview and career trajectory, exposing him firsthand to the Nazi Party's ascent—evident in street demonstrations and propaganda he observed—fostering a commitment to antifascist photojournalism that prioritized proximity to events over detached artistry.[15][16] By 1933, with Adolf Hitler's chancellorship and escalating antisemitic violence, Friedmann departed for Paris to evade persecution as a Jewish leftist, carrying rudimentary photographic equipment and contacts that would propel his professional reinvention.[13][17]Move to Paris and Early Professional Steps

In 1933, following the Nazi seizure of power in Germany, Endre Ernő Friedmann, then aged 19 or 20, fled Berlin for Paris to escape rising antisemitism and political persecution.[13][18] Arriving in September, he initially operated under variations of his name, such as André Friedmann, while scraping by as a freelance photographer in the city's vibrant but competitive expatriate community.[19] In Paris, Friedmann shared a makeshift darkroom with fellow photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson and David Seymour (Chim), fostering early networks in the émigré photography scene.[13] To enhance marketability amid economic hardship, he and his companion Gerta Pohorylle (later Gerda Taro), a Polish-Jewish refugee whom he met around this time, devised the pseudonym Robert Capa—portraying it as the identity of a fictional, glamorous American photographer whose images commanded premium prices.[10] This strategic reinvention allowed them to sell portraits and event photographs to European agencies and magazines, including early commissions for publicity shots of figures like actress Kiki de Montparnasse in 1934.[10] Capa's initial professional output in Paris focused on street scenes, political rallies, and celebrity portraits, often using a 35mm Leica camera for its portability and speed—tools that suited his improvisational style.[20] By 1935, he secured a role as a picture editor for the Paris branch of the Japanese magazine Akahata, handling image selection and distribution, which provided modest stability and exposure to international photo markets.[14] These steps marked his transition from amateur darkroom assistant to emerging photojournalist, though financial precarity persisted, with the pair living in a cramped apartment near the Eiffel Tower and relying on opportunistic sales.[14]Professional Career

Collaboration with Gerda Taro and Rise in Photojournalism

Robert Capa, originally Endre Friedmann, met Gerda Taro, born Gerta Pohorylle, in Paris in 1933 after both had fled antisemitism in Europe.[21] Their relationship evolved into a romantic and professional partnership, with Taro assisting Capa in darkroom work and promotion while developing her own photographic skills.[22] In 1935, to enhance marketability and obscure their Jewish identities amid rising fascism, they adopted the pseudonyms Robert Capa and Gerda Taro, fabricating personas as glamorous American photographers to command higher fees for their images.[22] The duo's collaboration intensified in 1936 when they traveled to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War, pioneering a close-up, immersive style of war photography that emphasized emotional impact over detached observation.[10] Taro initially credited some of Capa's photos under his name alone to build his reputation, but she soon established her distinct byline, with their joint output appearing in European magazines such as Vu and Regards.[23] This partnership marked Capa's ascent in photojournalism, as their innovative approach—getting perilously close to combat—yielded compelling visuals that elevated freelance photographers' status and influenced the genre's development toward humanistic, frontline reporting.[24] Taro's death on July 25, 1937, from injuries sustained when her car was struck by a tank during the Battle of Brunete, profoundly affected Capa, yet their combined legacy solidified his prominence, with over 4,500 negatives from their Spanish coverage later rediscovered, underscoring the volume and quality of their collaborative output.[25][26] Capa's rise was thus inextricably linked to Taro's contributions, transforming him from an obscure émigré into a sought-after war photographer whose work anticipated the ethical and stylistic norms of modern photojournalism.[10]Spanish Civil War Coverage (1936-1939)

Robert Capa arrived in Spain in August 1936, weeks after the military uprising that ignited the Spanish Civil War on July 17-18, 1936, accompanied by his partner Gerda Taro, with whom he collaborated professionally and romantically.[27][25] They documented the Republican Loyalist forces fighting Francisco Franco's Nationalist rebels, focusing on frontline combat and civilian impacts, with Capa emphasizing proximity to action under his principle of getting "close enough" to capture authenticity.[25] Their work appeared in publications like Vu magazine, highlighting the war's brutality from a pro-Republican perspective.[26] Capa's most iconic image from the war, The Falling Soldier (also known as Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death), depicts a Republican soldier tumbling backward after being struck by a bullet during an assault at Cerro Muriano near Córdoba on September 5, 1936.[28][29] First published in Vu on September 23, 1936, and later in Life magazine on July 12, 1937, the photograph became a symbol of the war's human cost but has faced ongoing scrutiny over its authenticity, with researchers like José Manuel Susperregui arguing in 2009 that landscape features and soldier identifications suggest staging or misattribution, possibly to nearby Espejo rather than Cerro Muriano.[30][31] Capa and institutions like the International Center of Photography maintain it captured a genuine moment, supported by contact sheets from rediscovered negatives in the "Mexican Suitcase" collection of over 4,500 images by Capa, Taro, and David Seymour (Chim), recovered in 2007.[26][32] Throughout 1937-1939, Capa covered major Republican offensives, including the Battle of Brunete in July 1937, where Taro was fatally injured on July 25 when a tank accidentally ran over her during retreat; she died the next day in Madrid at age 26.[23] He also documented the Teruel campaign in winter 1937-1938 and the Ebro offensive in 1938, capturing scenes of exhausted troops and devastated landscapes, such as Loyalist positions near Fraga on the Aragon front in November 1938.[33] These images, often developed under duress with lost originals complicating verification, underscored the Republicans' defensive struggles amid Nationalist advances bolstered by German and Italian support.[26] Capa's Spanish Civil War portfolio, totaling thousands of exposures, established his reputation for visceral war imagery, though debates persist over potential reconstructions due to the era's photojournalistic practices and lost evidence; nonetheless, the work influenced public perception in Europe and the U.S., aligning with anti-fascist sentiments while prioritizing raw combat documentation over staged propaganda.[25][26]Sino-Japanese War Assignment (1938)

In early 1938, shortly after the death of his professional partner and companion Gerda Taro in the Spanish Civil War, Robert Capa accepted an assignment to document the Second Sino-Japanese War, which had begun with Japan's full-scale invasion of China on July 7, 1937.[2] Arriving in spring 1938, Capa spent approximately eight months in the country, working primarily for international photo agencies and focusing on the Chinese Nationalist resistance against Japanese advances.[34] His coverage emphasized frontline preparations and civilian endurance, capturing the war's toll on a population mobilizing en masse, including the conscription of young recruits as Japanese forces pushed toward central China.[35] Capa established himself in Hankou (modern-day Wuhan), the temporary capital of the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek, where he documented urban life amid intensifying Japanese air raids and ground offensives. On April 29, 1938, he photographed civilians gathered on rooftops and streets, intently watching dogfights between Japanese bombers and Chinese fighters overhead, highlighting the precarious exposure of non-combatants to modern aerial warfare.[36] Other notable images included a 15-year-old soldier standing rigidly at attention before his unit's departure for key battles, underscoring the war's reliance on inexperienced youth amid resource shortages.[37] Capa made at least two extended visits to the Wuhan region, producing photographs that reversed typical Western gazes by centering Chinese agency and resilience during the Japanese siege.[38] During the assignment, Capa pioneered color photography in conflict reporting by requesting and using Kodachrome film, as evidenced by his July 27, 1938, letter to his New York agency urging the shipment of 12 rolls to capture the war's vivid scenes beyond monochrome limitations.[34] These efforts yielded early color images of troop movements and destruction, though many remained unpublished at the time due to the nascent technology's processing demands and editorial preferences for black-and-white drama.[35] Facing personal risks from bombings and logistical challenges in war-torn areas, Capa departed China by late 1938, relocating to New York in 1939 as global conflict loomed larger.[2] His Chinese portfolio, later archived and exhibited, contributed to his reputation for intimate, hazard-proximate war imagery, though it received less immediate acclaim than his Spanish work amid the West's divided sympathies on the Sino-Japanese front.World War II Engagements (1941-1945)

In 1941, Capa documented the aftermath of the German Blitz on London, capturing images of bombed-out neighborhoods and resilient civilians in areas like Waterloo Road for Collier's magazine during June and July.[39] His photographs emphasized the human endurance amid destruction, including the roofless interior of St. John's Church in a heavily bombed Cockney district.[39] By late 1942, Capa shifted to the North African theater, embedding with U.S. forces to photograph air and ground operations during the Allied campaign against Axis positions.[13] In 1943, he covered the Allied invasion of Sicily starting July 10, documenting intense fighting and civilian interactions, such as a Sicilian peasant directing an American officer on German troop movements.[40] He then followed the Italian campaign, entering Naples with Allied forces on October 1 and recording the hardships of urban combat and liberation, including civilians amid devastation such as a group of Neapolitan children scavenging debris.[41] Capa's work transitioned to LIFE magazine by 1943, where he continued frontline reporting, prioritizing proximity to combat to convey the raw realities of war.[42] His assignments culminated in the Normandy invasion and subsequent European advances, producing images that highlighted both tactical chaos and individual valor.D-Day Omaha Beach Landings (1944)

Robert Capa, working as a photographer for Life magazine, documented the initial assault on Omaha Beach during the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. He embarked aboard the USS Samuel Chase with Company E, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, landing at the Easy Red sector between approximately 7:40 and 8:20 a.m. local time, amid the second or third wave following heavy initial casualties from German defenses.[43] Under heavy German fire, he exposed approximately 106 frames over 90 minutes, wading through chest-deep surf littered with obstacles and bodies, taking cover behind a disabled tank and hedgehogs while advancing with troops to capture the assault's ferocity before retreating to a landing craft. Equipped with two 35mm Contax cameras loaded with black-and-white film, the images depict soldiers struggling through waves under fire, combat engineers wiring beach obstacles for demolition, and infantrymen seeking cover amid smoke, debris, and floating dead, including blurred figures conveying the disorientation and peril of the landing.[4] Due to a lab assistant's haste in London—developing films in a makeshift coal-heated enclosure and overheating them in a dryer—only 11 images, known as the "Magnificent Eleven," survived; the rest melted, their slight blur attributed to damp conditions, haste, and combat vibrations.[1] These were rush-published in Life's June 19, 1944, issue under the byline "Beachhead Don," with notable captions including "slightly out of focus," marking one of the first visual accounts of D-Day's bloodiest sector, where approximately 2,400 American troops were killed or wounded in the first day.[43] Capa's commitment to minimal cover—"if your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough"—enabled these visceral records, though he later described the experience as terrifying, with near-misses from bullets and shrapnel.[1]Other WWII Campaigns and Specific Images

Capa covered the Allied invasion of Sicily beginning July 10, 1943, embedding with U.S. forces during Operation Husky, which aimed to secure the island as a stepping stone to mainland Italy and contributed to Benito Mussolini's ouster on July 25. His photographs from the campaign, including scenes from the Battle of Troina on August 6, depicted exhausted American infantrymen amid rubble-strewn streets, soldiers navigating destroyed villages under fire, and a peasant woman gesturing to U.S. troops about fleeing Germans, capturing the grueling advance against German and Italian defenders with over 25,000 Allied casualties in the operation, including 2,300 U.S. losses in the week-long Troina fight. He also photographed paratroopers preparing for drops, emphasizing logistical strains and soldier fatigue.[40][44] Following Sicily's fall, Capa documented the Salerno landings on September 9, 1943, and the subsequent push northward. These works, distributed via LIFE and Collier's, prioritized unfiltered combat scenes over staged heroism, though Capa's selection process sometimes favored dramatic compositions to amplify impact. Beyond Normandy, Capa documented the Allied push into France, photographing reprisals against suspected collaborators in Chartres on August 16, 1944, including a woman publicly shaven and stripped by a crowd amid post-liberation purges that affected thousands across France, and the liberation of Paris on August 25, 1944, capturing jubilant crowds, French Resistance fighters, fighters atop vehicles, ecstatic throngs welcoming Free French and U.S. troops, and General Charles de Gaulle's parade down the Champs-Élysées, with over 1 million Parisians participating despite ongoing skirmishes that killed around 150 civilians and combatants until the city's full surrender on August 26.[45][46][47][48] By 1945, his coverage extended to Germany's collapse, but earlier theaters like North Africa yielded fewer surviving specifics, focusing on operational integration rather than singular icons. These works, preserved in archives like Magnum Photos and the International Center of Photography, underscore Capa's approach of proximity to conflict, though some prints reveal the era's technical limits, such as grainy exposures from handheld Contax cameras in low light.[13][49]Postwar Assignments (1947-1953)

Following World War II, Robert Capa undertook several significant photojournalistic assignments, leveraging his co-founding of Magnum Photos to secure access for in-depth coverage of postwar reconstruction and emerging conflicts. In 1947, he collaborated with American writer John Steinbeck on a 40-day journey through the Soviet Union, departing on July 31 and visiting Moscow, Kiev, Stalingrad (now Volgograd), and Georgia along the "Vodka Circuit."[50] The trip, conducted amid early Cold War tensions, focused on documenting everyday Soviet life, war devastation, and recovery efforts under strict official oversight, with Soviet agents monitoring their movements and suspecting espionage.[51] Capa's photographs, emphasizing human resilience amid scarcity—such as farmers rebuilding collective farms and families in modest homes—accompanied Steinbeck's text in the 1948 book A Russian Journal, published by Viking Press, which aimed to humanize the USSR for Western audiences despite controlled access limiting unfiltered views.[52] In 1948, Capa shifted to the Middle East to cover the Arab-Israeli War and Israel's founding, arriving in time for David Ben-Gurion's independence declaration on May 14 in Tel Aviv.[53] His work, spanning 1948 to 1950, captured the influx of Jewish immigrants, military operations, and nascent state-building, including the July 1948 Altalena affair where Israeli forces shelled an Irgun arms ship off Tel Aviv, as well as scenes of soldiers integrating former paramilitary groups into the Israel Defense Forces.[54] [55] Capa's images, distributed via Magnum, portrayed Israel as a determined homeland for Holocaust survivors and war victors, often foregrounding Jewish settlers and fighters while marginalizing Palestinian perspectives, reflecting his sympathetic lens toward the Zionist narrative amid the conflict's chaos.[56] These assignments yielded reports for magazines like Holiday, highlighting urban life in Tel Aviv and rural kibbutzim.[57] By the early 1950s, Capa's postwar work increasingly incorporated color photography for U.S. publications, documenting European recovery and cultural shifts, though specific film production coverage in this period built on earlier Hollywood forays like his 1946 shots of Alfred Hitchcock's Notorious.[58] Serving as Magnum's Paris office director from 1950 to 1953, he balanced administrative duties with freelance assignments emphasizing human stories over frontline combat, adapting to peacetime themes while maintaining his signature proximity to subjects.[59] This phase marked a transition from wartime intensity to broader journalistic exploration, though Capa expressed frustration with the era's relative calm compared to prior conflicts.[60]Soviet Union Visit (1947)

In 1947, Robert Capa traveled to the Soviet Union for a 40-day assignment from July 31 to mid-September, accompanied by American writer John Steinbeck, to document everyday life amid early Cold War tensions.[50][52] Their itinerary followed the so-called "Vodka Circuit," encompassing Moscow, Kiev, Stalingrad (now Volgograd), and Georgia, with a focus on post-World War II reconstruction and civilian conditions in war-damaged regions.[50][61] Capa's photographs captured urban scenes, public gatherings, and individual portraits, including images of visitors in Moscow's Red Square and women dancing in the streets, reflecting a society in staged recovery under Stalinist control.[50][62] Steinbeck's accompanying text, drawn from their observations, emphasized human resilience but noted restrictions on access, as the trip was highly choreographed by Soviet authorities to showcase approved narratives of progress.[63] The collaboration culminated in the 1948 book A Russian Journal, with Capa's images illustrating Steinbeck's account and distributed via the newly formed Magnum Photos agency.[50][64] Soviet secret police extensively monitored the pair, shadowing their movements and intercepting communications, while suspecting them of espionage on behalf of U.S. interests, according to declassified KGB reports from the era.[51] Despite these constraints, Capa's work provided rare Western visual insights into Soviet daily existence, later featured in exhibitions and publications highlighting the era's controlled optimism and underlying devastation.[65][66]Arab-Israeli War Coverage (1948)

In May 1948, Robert Capa arrived in Tel Aviv on May 8, assigned by Illustrated magazine to cover the unfolding conflict following the United Nations partition plan and amid escalating Arab-Israeli hostilities.[53] He immediately documented the declaration of Israel's independence on May 14, photographing David Ben-Gurion proclaiming the state's establishment at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, capturing the tension of the moment as sirens warned of incoming attacks.[53] [54] Capa embedded with Haganah forces during the early phases of the War of Independence, photographing troops marching to defend kibbutzim on the central front in May and civilians in trenches at a kibbutz under Arab air raid in May-June.[54] In late May, he traveled to the Negev to record the defense of Kibbutz Negba against Egyptian advances, emphasizing the makeshift fortifications and resolve of defenders.[53] By June, in Jerusalem, he covered the construction of the Burma Road to bypass Arab blockades and the funeral procession for American Colonel David "Mickey" Marcus, carried by Haganah soldiers.[53] His coverage culminated in the Altalena affair on June 22, when he photographed Israeli forces shelling the Irgun arms ship off Tel Aviv, including the burning vessel and fleeing crewmen; during the incident, Capa was grazed by a bullet.[53] [54] These images appeared in Life magazine on July 12, 1948, providing Western audiences with vivid accounts of the internal and external conflicts shaping the nascent state.[53] The bullet wound prompted his swift departure to Paris shortly thereafter, concluding his frontline war documentation in 1948.[53]Film Production Documentation (1950s)

In 1953, Robert Capa documented the on-location production of the film Beat the Devil in Ravello, Italy, along the Amalfi Coast.[67] Directed by John Huston, the film adapted Claud Cockburn's novel of the same name, with screenplay credited to Huston and Truman Capote.[68] Capa, who accompanied Huston and Capote during filming, captured candid behind-the-scenes images of the cast and crew, including stars Humphrey Bogart, Gina Lollobrigida, Peter Lorre, and George Sanders.[67] [68] His photographs emphasized the relaxed atmosphere amid the production's challenges, such as Bogart's on-set chess games with Sanders and interactions among the principals during breaks.[69] This assignment marked a shift from Capa's typical war zones, showcasing Hollywood glamour and interpersonal dynamics in a non-combat setting, with some images taken in color to highlight the vibrant Italian locale.[70] Off-camera, Capa socialized with Bogart, Huston, and Capote, blending professional duties with leisure in the hillside town.[67] The resulting portfolio, published in outlets like Holiday magazine, provided rare glimpses into the improvisational style of the low-budget production, which faced logistical hurdles including Bogart's health issues and script revisions.[68] Capa's work underscored his versatility as a photojournalist, applying his intimate, action-oriented approach to civilian creative endeavors shortly before his fatal assignment in Indochina the following year.[71] No other major film production documentation by Capa is recorded in the early 1950s, as his focus remained primarily on Magnum Photos agency duties and international assignments until May 1954.[59]First Indochina War and Final Assignment (1954)

In early May 1954, shortly after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu on May 7, Robert Capa received an assignment from Life magazine to document ongoing French military operations in Indochina amid the collapsing colonial effort against the Viet Minh. Having been in Japan for a Magnum Photos exhibition, Capa volunteered for the mission, traveling to Hanoi and embedding with French forces in Thái Bình Province, approximately 45 miles southeast of the capital.[42] [72] On May 25, Capa joined a convoy of French paratroopers from the 2nd Foreign Legion Parachute Battalion, alongside Time and Life journalists John Mecklin and Jim Lucas, as they advanced through rice paddies between Nam Định and Thái Bình to clear Viet Minh remnants during the French withdrawal phase.[73] While photographing the troops fording a stream and advancing on foot to evade detection, Capa moved ahead of the group to capture closer images, stepping on an anti-personnel landmine planted by Viet Minh forces.[73] [72] The explosion severely wounded his legs and torso; evacuated by helicopter to a Hanoi hospital, he succumbed to his injuries en route or shortly after arrival, at age 40.[42] Capa's final photographs, taken with a Nikon camera just moments before the blast, depicted Vietnamese troops—likely Viet Minh fighters—in motion across the flooded terrain, marking the last images from a career defined by frontline proximity.[73] These prints, developed posthumously, appeared in the June 7, 1954, issue of Life, underscoring the perils of his "if your picture isn't good enough, you're not close enough" ethos amid a war that ended with the Geneva Accords on July 21.[42] His death, the only combat fatality among Western journalists in that conflict, highlighted the hazards of post-surrender skirmishes and prompted reflections on the ethical boundaries of war photography.[72]Professional Organizations and Innovations

Co-Founding Magnum Photos (1947)

In the aftermath of World War II, Robert Capa initiated the formation of Magnum Photos in 1947 as a cooperative agency owned and operated by its photographer-members, aiming to preserve their editorial and financial independence from magazine publishers.[74] Joining Capa as founding photographers were Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger, and David "Chim" Seymour, each bringing distinct experiences from wartime and postwar documentation.[74] Capa, leveraging his reputation from covering major conflicts, served as the driving force, organizing pivotal discussions to outline the agency's democratic structure and operational principles.[2] The cooperative model emphasized photographer autonomy, with members retaining copyrights to their images and receiving a portion of reproduction fees, which contrasted sharply with prevailing practices where agencies or editors dictated usage and compensation.[74] This framework supported ethical, in-depth storytelling by allowing contributors to select and edit their own work, fostering a blend of journalistic rigor and artistic expression amid postwar reconstruction efforts.[74] Early formalization occurred through meetings, including one convened by Capa in New York in May 1947 involving figures like Maria Eisner and William Vandivert, which helped establish administrative foundations.[75] Magnum's Paris headquarters facilitated international distribution, while a New York office at 55 West 8th Street, initially overseen by Rita Vandivert, expanded its reach to American markets.[76] The venture's emphasis on collective ownership enabled sustained fieldwork without immediate commercial pressures, positioning Magnum as a bulwark for photojournalistic integrity in an era of recovering global media landscapes.[74]Contributions to Photojournalistic Practices

Capa pioneered a proximity-based approach to war photography, emphasizing immersion in the action to capture authentic human experiences rather than distant observations, which marked a departure from earlier detached perspectives in conflict documentation.[20] His photographs from the Spanish Civil War, such as the 1936 image of a Loyalist militiaman falling to his death, exemplified this method by prioritizing visceral immediacy over safety, influencing subsequent photographers to prioritize on-the-ground engagement.[77] This technique, enabled by the portable 35mm Leica camera and faster film stocks available in the 1930s, allowed for candid shots under duress, setting a standard for mobility and spontaneity in photojournalism.[20] His oft-quoted maxim, "If your pictures aren't good enough, you aren't close enough," encapsulated a philosophy that demanded ethical commitment to subjects, humanizing combatants and civilians alike to convey war's personal toll.[78] This ethos extended to his World War II coverage, including the 1944 D-Day landings at Omaha Beach, where only 11 surviving frames from 108 exposures underscored the risks of such proximity while establishing benchmarks for intensity in visual storytelling. Capa's work with magazines like Life further integrated photographs into narrative photo-essays, elevating the medium's role in public discourse by blending artistry with reportage.[42] As co-founder of Magnum Photos in 1947 alongside Henri Cartier-Bresson and others, Capa helped institutionalize photographer autonomy through a cooperative agency model that retained copyrights and editorial control, countering exploitation by publishers.[13] Magnum's structure fostered long-term projects and ethical distribution, enabling in-depth coverage of global events and reinforcing photojournalism's capacity to document the human condition compassionately and independently.[79] This innovation democratized access to high-quality imagery while prioritizing narrative depth over commercial sensationalism, influencing the field's professional standards into the postwar era.[25]Personal Life

Key Relationships and Partnerships

Robert Capa's closest personal and professional partnership was with Gerda Taro (born Gerta Pohorylle), a German-Jewish photojournalist he met in Paris in the early 1930s.[80] Their romantic relationship intertwined with a collaborative effort to establish themselves in photojournalism; Taro assisted in fabricating the "Robert Capa" identity for Friedmann to command premium prices for their images, marketing him as a fictional American photographer.[25] Together, they covered the Spanish Civil War starting in 1936, producing frontline images that elevated their reputations, though Taro increasingly pursued independent work under her own byline.[10] Taro's death on July 25, 1937, from injuries sustained when a tank struck her vehicle during the Battle of Brunete profoundly affected Capa, occurring just months after he had proposed marriage, which she declined while maintaining their bond.[21] No other long-term romantic partnerships are prominently documented in Capa's biography following Taro, with his life centered on transient wartime assignments and professional networks. Professionally, Capa forged enduring collaborations through the co-founding of Magnum Photos in 1947 alongside Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger, and David "Chim" Seymour, establishing a photographer-owned agency emphasizing editorial independence and collective storytelling.[81] This partnership enabled shared resources, distribution, and ethical standards amid postwar journalism, with Capa serving as a driving force in its early operations and recruitment.[82] His brother, Cornell Capa, later joined Magnum in 1954, continuing familial ties in photojournalism after Robert's death.[78]Lifestyle, Health, and Personal Habits

Capa maintained a bohemian and high-risk lifestyle characterized by frequent travel across Europe and beyond for photographic assignments, often living out of hotels and associating with intellectuals, artists, and fellow photojournalists in cities like Paris and New York.[20] His personal habits included heavy gambling, influenced by his father's occupation and stories, encompassing poker games, horse betting, and a general appetite for wagers that mirrored the dangers he courted in war zones.[9][83] A habitual smoker, Capa was frequently photographed with cigarettes, including during informal moments and even using one to illuminate film development under makeshift conditions in the field.[84][85] He was also known as a hard drinker, with alcohol consumption forming part of his social routine and coping mechanism amid the stresses of combat coverage, as detailed in biographical accounts of his postwar years.[77][86] Capa's health showed early signs of strain from these habits and repeated exposure to trauma; by the late 1940s, he exhibited symptoms akin to post-traumatic stress disorder, including restlessness and heavy indulgence, though he continued high-stakes assignments until his fatal injury in 1954 at age 40.[87] His risk-tolerant personality extended to personal pursuits, such as impulsively taking up skiing without training, underscoring a broader pattern of embracing uncertainty.[88]Political Involvement

Antifascist Stance and Republican Sympathies

Robert Capa, born Endre Ernő Friedmann in Budapest in 1913 to Jewish parents, developed an early opposition to authoritarianism influenced by the anti-fascist and pacifist writings of Lajos Kassák.[89] At age 18, he was arrested by Hungary's secret police for participating in illegal protests against the Horthy regime, which exhibited authoritarian and anti-Semitic tendencies.[89] This incident prompted his exile from Hungary in 1931, as authorities cracked down on anti-government activities amid rising fascist influences in Europe.[90] Capa's antifascist convictions deepened in Berlin, where he witnessed the Nazi rise, and in Paris, where he collaborated with leftist intellectuals and photographers.[91] These experiences positioned him as an ardent antifascist prior to the Spanish Civil War's outbreak on July 17, 1936.[92] Viewing fascism as an existential threat, Capa rejected neutrality in conflicts pitting democratic or leftist forces against authoritarian regimes.[93] In September 1936, Capa arrived in Spain to document the Republican defense against General Francisco Franco's Nationalist forces, backed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.[25] His sympathies aligned firmly with the Republican coalition—comprising socialists, communists, anarchists, and liberals—whom he saw as antifascist resistors preserving democratic gains from the 1931 Second Republic.[25] Capa's photographic work, including iconic images like The Falling Soldier (1936), served to rally international support for the Republican cause, portraying their fighters with heroic immediacy to counter fascist propaganda.[93] He described the war as an emotional and ideological commitment, prioritizing proximity to Republican militias to capture the human cost of antifascist resistance.[25] This partisan alignment reflected Capa's broader rejection of fascism, informed by personal exile and European political upheavals, rather than detached journalism; he explicitly believed in the Republican struggle as a bulwark against totalitarian expansion.[94] Despite internal Republican divisions and Soviet influence, Capa's output emphasized unified antifascist resolve, influencing global perceptions of the conflict as a prelude to World War II.[33]Engagement with Communist and Leftist Causes

Capa's early exposure to leftist politics occurred in Hungary during his adolescence. In 1931, at age 17, he participated in student protests against police, leading to his arrest by secret police on charges of conspiring with the illegal Communist Party, though he was released after intervention by his mother.[14] [95] These accusations of communist sympathies prompted his departure from Hungary in 1931, first to Vienna and then Prague, amid rising political repression.[96] While Capa expressed sympathy for left-wing movements and met members of underground communist networks, no evidence confirms formal membership in the Communist Party.[97] His engagement deepened through personal relationships and antifascist commitments in Europe. In Paris, Capa formed a romantic and professional partnership with Gerda Taro (born Gerda Pohorylles), a German-Jewish communist activist and photographer who shared his opposition to fascism.[93] Taro's explicit communist affiliations influenced their joint work, including coverage of leftist demonstrations and the rise of Nazism in Berlin, where Capa photographed Leon Trotsky in Copenhagen in 1932 amid street clashes between socialists, Nazis, and communists.[98] This period aligned Capa with broader leftist antifascist circles, though his own stance emphasized democratic republicanism over strict ideological adherence. During the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), Capa actively supported the Republican side—a coalition including socialists, anarchists, and communists—against Franco's Nationalists, viewing the conflict as a frontline against fascism. He embedded with Loyalist militias, producing iconic images like The Falling Soldier (1936), which served propagandistic purposes to garner international sympathy for the Republican cause.[99] His 1938 photobook Death in the Making, co-authored with Taro, explicitly aimed to raise awareness and aid for Republican Spain, reflecting partisan commitment: as Capa stated, in war one must "hate somebody or love somebody."[93] This involvement extended to publishing in left-leaning outlets and associating with antifascist intellectuals, though post-war scrutiny by U.S. authorities in the 1940s investigated unsubstantiated claims of communist ties, ultimately finding insufficient evidence.[100] Later reflections suggest Capa distanced himself from communism. By the mid-1930s, he reportedly developed disdain for communists, prioritizing antifascism without endorsing Soviet-aligned factions within leftist movements.[90] His coverage evolved toward humanist journalism, as seen in Magnum Photos' cooperative ethos, which avoided overt ideological propaganda.[33]Coverage of Israel and Shifting Perspectives

In May 1948, Robert Capa arrived in the newly declared State of Israel shortly after David Ben-Gurion's proclamation of independence on May 14 at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, where he captured photographs of the event and the ensuing Arab-Israeli War.[53] His coverage included frontline scenes such as the defense of Kibbutz Negba in late May, the construction of the Burma Road in June to supply Jerusalem, the funeral of American-Israeli officer Mickey Marcus on June 11, and the Altalena affair on June 22, during which Capa photographed the Irgun ship under fire from Israeli forces and was grazed by a bullet while working from a Tel Aviv hotel balcony.[53] These images emphasized the immediacy of combat and nation-building efforts amid existential threats.[57] Capa returned for additional trips in 1949 and 1950, producing a total of 303 published photographs that documented immigrant arrivals in Haifa, daily life in kibbutzim like Kfar Giladi, Hebrew schools, transit camps for Bulgarian refugees, and military figures including Moshe Dayan and Yitzhak Sadeh.[57] His work portrayed Israel as a dynamic, resilient society of Holocaust survivors and pioneers forging a homeland, often through lyrical depictions of labor, community, and victory, which contributed to Western legitimization of the state's founding.[53] Analyses note that Capa's lens ideologically framed Israel heroically while largely excluding Palestinian civilians and contexts, reflecting selective access and his focus on the Jewish narrative during wartime restrictions.[56] Initially skeptical of Zionism due to his leftist, non-aligned background, Capa underwent a perceptible shift after immersing in Israel's early struggles, expressing in a June 21, 1948, interview with Al Ha-mishmar that "I was never a Zionist, and I’m not one now either, but… I am now convinced that for most of the world’s Jews there is no other solution except Israel."[53] This evolution aligned with his antifascist sympathies and firsthand observation of Jewish determination post-World War II, viewing the state as a pragmatic refuge rather than an ideological cause, though he maintained reservations about certain internal conflicts like the Altalena incident.[53] His subsequent trips and imagery suggest sustained engagement with Israel's viability, contrasting his prior disinterest in Zionist movements.[57]Photographic Technique and Style

Core Philosophy: Proximity to Action

Robert Capa's core philosophy in war photography emphasized extreme proximity to the subject, encapsulated in his oft-quoted maxim: "If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough." This principle, articulated as a directive for capturing the raw essence of conflict, compelled photographers to immerse themselves amid the chaos rather than observe from a safe distance, thereby conveying the human cost and immediacy of violence. Capa applied this ethos consistently across conflicts, positioning himself alongside combatants to document unfiltered moments of peril and emotion, which he believed distinguished authentic photojournalism from detached reportage.[101][102] This approach stemmed from Capa's conviction that emotional impact required visceral closeness, achieved through lightweight 35mm cameras like the Contax or Leica, which enabled mobility and rapid shooting in hazardous environments. By forgoing bulky equipment favored by some contemporaries, Capa prioritized agility, allowing him to advance with infantry during assaults, as seen in his D-Day coverage on Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944, where he exposed 108 frames amid gunfire before retreating under fire. His method rejected staged or composed scenes in favor of spontaneous captures, arguing that distance diluted truth; proximity, conversely, risked the photographer's life but yielded images that humanized soldiers and civilians alike, fostering public empathy for war's brutality.[20][4][42] Critics and peers have noted that this philosophy, while pioneering, blurred lines between journalism and personal endangerment, influencing generations of photographers to adopt "in-the-trenches" tactics. Capa defended it as essential for transcending mere documentation, insisting that only by sharing soldiers' risks could images pierce viewer indifference; he reportedly embodied this during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), advancing to Loyalist frontlines despite mortal threats. Though some later analyses question the verifiability of every close-range shot, the principle's enduring advocacy for bold, empathetic fieldwork solidified Capa's reputation as a transformative figure in visual storytelling.[102][53]Technical Methods and Equipment Use

Capa favored compact 35mm rangefinder cameras for their portability, enabling him to maneuver swiftly in combat zones and maintain proximity to subjects.[103] Early work, such as portraits of Leon Trotsky in Copenhagen in 1931, utilized the Leica II.[103] During the Spanish Civil War from 1936 to 1939, he relied on the Leica III or IIIa models, which supported rapid handheld shooting amid chaotic frontline conditions.[103][104] By the late 1930s, Capa shifted to the Zeiss Ikon Contax II as his primary instrument, valuing its robust build and interchangeable lenses for extended war coverage.[103][104] This camera, equipped with a 50mm f/1.5 Carl Zeiss Sonnar lens, featured prominently in assignments like the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1938 and the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, where he carried two Contax II bodies loaded with Kodak Super-XX film stock to capture fast-action sequences under fire.[103][104][105] The fast aperture of the Sonnar lens allowed for effective exposure in low-light battlefield scenarios, prioritizing mobility over tripod stability.[104] For less dynamic portraits and composed scenes, particularly during World War II, Capa incorporated twin-lens reflex cameras such as the Rolleiflex Automat Model RF or Old Standard, which permitted precise focusing and medium-format detail without the rangefinder's haste.[103] In his final assignment in French Indochina in 1954, he combined a Contax II for black-and-white work with the newer Nikon S rangefinder fitted with Nikkor lenses and color film, adapting to emerging postwar trends in chromatic documentation.[103][104] His technical approach emphasized minimalism and immediacy: handheld operation to freeze fleeting moments, often accepting minor focus inconsistencies from subject motion or environmental hazards like sand and seawater during D-Day, rather than prioritizing studio-like sharpness.[103][104] Capa loaded multiple rolls of high-speed panchromatic film to sustain continuous shooting bursts, forgoing bulky large-format gear like the Graflex Speed Graphic, which he occasionally used for static setups but deemed impractical for frontline immersion.[103] This gear selection and method—lightweight 35mm systems with prime lenses—facilitated his doctrine of extreme closeness, yielding gritty, motion-infused images that conveyed war's visceral reality over polished aesthetics.[104][106]Aesthetic Choices and Composition