Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rolling circle replication

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) |

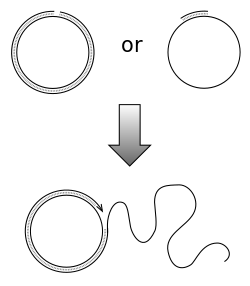

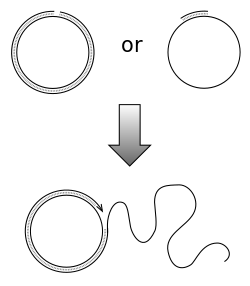

Rolling circle replication (RCR) is a process of unidirectional nucleic acid replication that can rapidly synthesize multiple copies of circular molecules of DNA or RNA, such as plasmids, the genomes of bacteriophages, and the circular RNA genome of viroids. Some eukaryotic viruses also replicate their DNA or RNA via the rolling circle mechanism.

As a simplified version of natural rolling circle replication, an isothermal DNA amplification technique, rolling circle amplification was developed. The RCA mechanism is widely used in molecular biology and biomedical nanotechnology, especially in the field of biosensing (as a method of signal amplification).[1]

Circular DNA replication

[edit]

Rolling circle DNA replication is initiated by an initiator protein encoded by the plasmid or bacteriophage DNA, which nicks one strand of the double-stranded, circular DNA molecule at a site called the double-strand origin, or DSO. The initiator protein remains bound to the 5' phosphate end of the nicked strand, and the free 3' hydroxyl end is released to serve as a primer for DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase III. Using the unnicked strand as a template, replication proceeds around the circular DNA molecule, displacing the nicked strand as single-stranded DNA. Displacement of the nicked strand is carried out by a host-encoded helicase called PcrA (the abbreviation standing for plasmid copy reduced) in the presence of the plasmid replication initiation protein.

Continued DNA synthesis can produce multiple single-stranded linear copies of the original DNA in a continuous head-to-tail series called a concatemer. These linear copies can be converted to double-stranded circular molecules through the following process:

First, the initiator protein makes another nick in the DNA to terminate synthesis of the first (leading) strand. RNA polymerase and DNA polymerase III then replicate the single-stranded origin (SSO) DNA to make another double-stranded circle. DNA polymerase I removes the primer, replacing it with DNA, and DNA ligase joins the ends to make another molecule of double-stranded circular DNA.

As a summary, a typical DNA rolling circle replication has five steps:[2]

- Circular dsDNA will be "nicked".

- The 3' end is elongated using "unnicked" DNA as leading strand (template); 5' end is displaced.

- Displaced DNA is a lagging strand and is made double stranded via a series of Okazaki fragments.

- Replication of both "unnicked" and displaced ssDNA.

- Displaced DNA circularizes.

Virology

[edit]Replication of viral DNA

[edit]Some DNA viruses replicate their genomic information in host cells via rolling circle replication. For instance, human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6)(hibv) expresses a set of "early genes" that are believed to be involved in this process.[3] The long concatemers that result are subsequently cleaved between the pac-1 and pac-2 regions of HHV-6's genome by ribozymes when it is packaged into individual virions.[4]

Human Papillomavirus-16 (HPV-16) is another virus that employs rolling replication to produce progeny at a high rate. HPV-16 infects human epithelial cells and has a double stranded circular genome. During replication, at the origin, the E1 hexamer wraps around the single strand DNA and moves in the 3' to 5' direction. In normal bidirectional replication, the two replication proteins will disassociate at time of collision, but in HPV-16 it is believed that the E1 hexamer does not disassociate, hence leading to a continuous rolling replication. It is believed that this replication mechanism of HPV may have physiological implications into the integration of the virus into the host chromosome and eventual progression into cervical cancer.[5]

In addition, geminivirus also utilizes rolling circle replication as its replication mechanism. It is a virus that is responsible for destroying many major crops, such as cassava, cotton, legumes, maize, tomato and okra. The virus has a circular, single stranded, DNA that replicates in host plant cells. The entire process is initiated by the geminiviral replication initiator protein, Rep, which is also responsible for altering the host environment to act as part of the replication machinery. Rep is also strikingly similar to most other rolling replication initiator proteins of eubacteria, with the presence of motifs I, II, and III at is N terminus. During the rolling circle replication, the ssDNA of geminivirus is converted to dsDNA and Rep is then attached to the dsDNA at the origin sequence TAATATTAC. After Rep, along with other replication proteins, binds to the dsDNA it forms a stem loop where the DNA is then cleaved at the nanomer sequence causing a displacement of the strand. This displacement allows the replication fork to progress in the 3’ to 5’ direction which ultimately yields a new ssDNA strand and a concatameric DNA strand.[6]

Bacteriophage T4 DNA replication intermediates include circular and branched circular concatemeric structures.[7] These structures likely reflect a rolling circle mechanism of replication.

Replication of viral RNA

[edit]Some RNA viruses and viroids also replicate their genome through rolling circle RNA replication. For viroids, there are two alternative RNA replication pathways that respectively followed by members of the family Pospiviroidae (asymmetric replication) and Avsunviroidae (symmetric replication).

In the family Pospiviroidae (PSTVd-like), the circular plus strand RNA is transcribed by a host RNA polymerase into oligomeric minus strands and then oligomeric plus strands.[8] These oligomeric plus strands are cleaved by a host RNase and ligated by a host RNA ligase to reform the monomeric plus strand circular RNA. This is called the asymmetric pathway of rolling circle replication. The viroids in the family Avsunviroidae (ASBVd-like) replicate their genome through the symmetric pathway of rolling circle replication.[9] In this symmetric pathway, oligomeric minus strands are first cleaved and ligated to form monomeric minus strands, and then are transcribed into oligomeric plus strands. These oligomeric plus strands are then cleaved and ligated to reform the monomeric plus strand. The symmetric replication pathway was named because both plus and minus strands are produced the same way.

Cleavage of the oligomeric plus and minus strands is mediated by the self-cleaving hammerhead ribozyme structure present in the Avsunviroidae, but such structure is absent in the Pospiviroidae.[10]

Rolling circle amplification (RCA)

[edit]

The derivative form of rolling circle replication has been successfully used for amplification of DNA from very small amounts of starting material.[1] This amplification technique is named as rolling circle amplification (RCA). Different from conventional DNA amplification techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), RCA is an isothermal nucleic acid amplification technique where the polymerase continuously adds single nucleotides to a primer annealed to a circular template which results in a long concatemer ssDNA that contains tens to hundreds of tandem repeats (complementary to the circular template).[11]

There are five important components required for performing a RCA reaction:

- A DNA polymerase

- A suitable buffer that is compatible with the polymerase.

- A short DNA or RNA primer

- A circular DNA template

- Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs)

The polymerases used in RCA are Phi29, Bst, and Vent exo-DNA polymerase for DNA amplification, and T7 RNA polymerase for RNA amplification. Since Phi29 DNA polymerase has the best processivity and strand displacement ability among all aforementioned polymerases, it has been most frequently used in RCA reactions. Different from polymerase chain reaction (PCR), RCA can be conducted at a constant temperature (room temperature to 65C) in both free solution and on top of immobilized targets (solid phase amplification).

There are typically three steps involved in a DNA RCA reaction:

- Circular template ligation, which can be conducted via template mediated enzymatic ligation (e.g., T4 DNA ligase) or template-free ligation using special DNA ligases (i.e., CircLigase).

- Primer-induced single-strand DNA elongation. Multiple primers can be employed to hybridize with the same circle. As a result, multiple amplification events can be initiated, producing multiple RCA products ("Multiprimed RCA").

- Amplification product detection and visualization, which is most commonly conducted through fluorescent detection, with fluorophore-conjugated dNTP, fluorophore-tethered complementary or fluorescently-labeled molecular beacons. In addition to the fluorescent approaches, gel electrophoresis is also widely used for the detection of RCA product.

RCA produces a linear amplification of DNA, as each circular template grows at a given speed for a certain amount of time. To increase yield and achieve exponential amplification as PCR does, several approaches have been investigated. One of them is the hyperbranched rolling circle amplification or HRCA, where primers that anneal to the original RCA products are added, and also extended.[12] In this way the original RCA creates more template that can be amplified. Another is circle to circle amplification or C2CA, where the RCA products are digested with a restriction enzyme and ligated into new circular templates using a restriction oligo, followed by a new round of RCA with a larger amount of circular templates for amplification.[13]

Applications of RCA

[edit]

RCA can amplify a single molecular binding event over a thousandfold, making it particularly useful for detecting targets with ultra-low abundance. RCA reactions can be performed in not only free solution environments, but also on a solid surface like glass, micro- or nano-bead, microwell plates, microfluidic devices or even paper strips. This feature makes it a very powerful tool for amplifying signals in solid-phase immunoassays (e.g., ELISA). In this way, RCA is becoming a highly versatile signal amplification tool with wide-ranging applications in genomics, proteomics, diagnosis and biosensing.

Immuno-RCA

[edit]Immuno-RCA is an isothermal signal amplification method for high-specificity & high-sensitivity protein detection and quantification. This technique combines two fields: RCA, which allows nucleotide amplification, and immunoassay, which uses antibodies specific to intracellular or free biomarkers. As a result, immuno-RCA gives a specific amplified signal (high signal-to-noise ratio), making it suitable for detecting, quantifying and visualizing low abundance proteic markers in liquid-phase immunoassays[14][15][16] and immunohistochemistry.

Immuno-RCA follows a typical immuno-adsorbent reaction in ELISA or immunohistochemistry tissue staining.[17] The detection antibodies used in immuno-RCA reaction are modified by attaching a ssDNA oligonucleotide on the end of the heavy chains. So the Fab (Fragment, antigen binding) section on the detection antibody can still bind to specific antigens and the oligonucleotide can serve as a primer of the RCA reaction.

The typical antibody mediated immuno-RCA procedure is as follows:

1. A detection antibody recognizes a specific proteic target. This antibody is also attached to an oligonucleotide primer.

2. When circular DNA is present, it is annealed, and the primer matches to the circular DNA complementary sequence.

3. The complementary sequence of the circular DNA template is copied hundreds of times and remains attached to the antibody.

4. RCA output (elongated ssDNA) is detected with fluorescent probes using a fluorescent microscope or a microplate reader.

In addition to antibody mediated immuno-RCA, the ssDNA RCA primer can be conjugated to the 3' end of a DNA aptamer as well. The primer tail can be amplified through rolling circle amplification. The product can be visualized through the labeling of fluorescent reporter.[18] The process is illustrated in the figure on the right.[19]

Other applications of RCA

[edit]Various derivatives of RCA were widely used in the field of biosensing. For example, RCA has been successfully used for detecting the existence of viral and bacterial DNA from clinical samples,[20][21] which is very beneficial for rapid diagnostics of infectious diseases. It has also been used as an on-chip signal amplification method for nucleic acid (for both DNA and RNA) microarray assay.[1]

In addition to the amplification function in biosensing applications, RCA technique can be applied to the construction of DNA nanostructures and DNA hydrogels as well. The products of RCA can also be use as templates for periodic assembly of nanospecies or proteins, synthesis of metallic nanowires[22] and formation of nano-islands.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Ali, M. Monsur; Li, Feng; Zhang, Zhiqing; Zhang, Kaixiang; Kang, Dong-Ku; Ankrum, James A.; Le, X. Chris; Zhao, Weian (2014). "Rolling circle amplification: a versatile tool for chemical biology, materials science and medicine". Chemical Society Reviews. 43 (10): 3324–41. doi:10.1039/C3CS60439J. PMID 24643375.

- ^ Demidov, Vadim V, ed. (2016). Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) - Toward New Clinical | Vadim V. Demidov | Springer. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-42226-8. ISBN 9783319422244. S2CID 30024718.

- ^ Arbuckle, Jesse (2011). "The molecular biology of human herpesvirus-6 latency and telomere integration". Microbes and Infection. 13 (8–9): 731–741. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2011.03.006. PMC 3130849. PMID 21458587.

- ^ Borenstein, Ronen; Frenkel, Niza (2009). "Cloning human herpes virus 6A genome into bacterial artificial chromosomes and study of DNA replication intermediates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (45): 19138–19143. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10619138B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908504106. PMC 2767366. PMID 19858479.

- ^ Kusumoto-Matsuo, Rika; Kanda, Tadahito; Kukimoto, Iwao (2011-01-01). "Rolling circle replication of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA in epithelial cell extracts". Genes to Cells. 16 (1): 23–33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01458.x. ISSN 1365-2443. PMID 21059156. S2CID 30493728.

- ^ Rizvi, Irum; Choudhury, Nirupam Roy; Tuteja, Narendra (2015-02-01). "Insights into the functional characteristics of geminivirus rolling-circle replication initiator protein and its interaction with host factors affecting viral DNA replication". Archives of Virology. 160 (2): 375–387. doi:10.1007/s00705-014-2297-7. ISSN 0304-8608. PMID 25449306. S2CID 16502010.

- ^ Bernstein H, Bernstein C (July 1973). "Circular and branched circular concatenates as possible intermediates in bacteriophage T4 DNA replication". J. Mol. Biol. 77 (3): 355–61. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(73)90443-9. PMID 4580243.

- ^ Daròs, José-Antonio; Elena, Santiago F.; Flores, Ricardo (June 2006). "Viroids: an Ariadne's thread into the RNA labyrinth". EMBO Reports. 7 (6): 593–598. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400706. ISSN 1469-221X. PMC 1479586. PMID 16741503.

- ^ Tsagris, Efthimia Mina; Martínez de Alba, Ángel Emilio; Gozmanova, Mariyana; Kalantidis, Kriton (2008-11-01). "Viroids". Cellular Microbiology. 10 (11): 2168–2179. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01231.x. hdl:10662/23889. ISSN 1462-5822. PMID 18764915.

- ^ Flores, Ricardo; Gas, María-Eugenia; Molina-Serrano, Diego; Nohales, María-Ángeles; Carbonell, Alberto; Gago, Selma; De la Peña, Marcos; Daròs, José-Antonio (2009-09-14). "Viroid Replication: Rolling-Circles, Enzymes and Ribozymes". Viruses. 1 (2): 317–334. doi:10.3390/v1020317. PMC 3185496. PMID 21994552.

- ^ Ali, M. Monsur; Li, Feng; Zhang, Zhiqing; Zhang, Kaixiang; Kang, Dong-Ku; Ankrum, James A.; Le, X. Chris; Zhao, Weian (2014-05-21). "Rolling circle amplification: a versatile tool for chemical biology, materials science and medicine". Chemical Society Reviews. 43 (10): 3324–3341. doi:10.1039/c3cs60439j. ISSN 1460-4744. PMID 24643375.

- ^ Lizardi, Paul M.; Huang, Xiaohua; Zhu, Zhengrong; Bray-Ward, Patricia; Thomas, David C.; Ward, David C. (July 1998). "Mutation detection and single-molecule counting using isothermal rolling-circle amplification". Nature Genetics. 19 (3): 225–232. doi:10.1038/898. ISSN 1546-1718. PMID 9662393. S2CID 21007563.

- ^ Dahl, Fredrik; Banér, Johan; Gullberg, Mats; Mendel-Hartvig, Maritha; Landegren, Ulf; Nilsson, Mats (2004-03-30). "Circle-to-circle amplification for precise and sensitive DNA analysis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (13): 4548–4553. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.4548D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0400834101. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 384784. PMID 15070755.

- ^ Schweitzer, Barry; Roberts, Scott; Grimwade, Brian; Shao, Weiping; Wang, Minjuan; Fu, Qin; Shu, Quiping; Laroche, Isabelle; Zhou, Zhimin (April 2002). "Multiplexed protein profiling on microarrays by rolling-circle amplification". Nature Biotechnology. 20 (4): 359–365. doi:10.1038/nbt0402-359. ISSN 1087-0156. PMC 2858761. PMID 11923841.

- ^ Zhou, Long; Ou, Li-Juan; Chu, Xia; Shen, Guo-Li; Yu, Ru-Qin (2007). "Aptamer-Based Rolling Circle Amplification: A Platform for Electrochemical Detection of Protein". Analytical Chemistry. 79 (19): 7492–7500. doi:10.1021/ac071059s. PMID 17722881.

- ^ Björkesten, Johan; Patil, Sourabh; Fredolini, Claudia; Lönn, Peter; Landegren, Ulf (2020-05-29). "A multiplex platform for digital measurement of circular DNA reaction products". Nucleic Acids Research. 48 (13) gkaa419. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa419. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 7367203. PMID 32469060.

- ^ Gusev, Y.; Sparkowski, J.; Raghunathan, A.; Ferguson, H.; Montano, J.; Bogdan, N.; Schweitzer, B.; Wiltshire, S.; Kingsmore, S. F. (July 2001). "Rolling circle amplification: a new approach to increase sensitivity for immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry". The American Journal of Pathology. 159 (1): 63–69. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61674-4. ISSN 0002-9440. PMC 1850404. PMID 11438455.

- ^ Zhou, Long; Ou, Li-Juan; Chu, Xia; Shen, Guo-Li; Yu, Ru-Qin (2007-10-01). "Aptamer-Based Rolling Circle Amplification: A Platform for Electrochemical Detection of Protein". Analytical Chemistry. 79 (19): 7492–7500. doi:10.1021/ac071059s. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 17722881.

- ^ Zhao, Weian; Ali, M. Monsur; Brook, Michael A.; Li, Yingfu (2008-08-11). "Rolling Circle Amplification: Applications in Nanotechnology and Biodetection with Functional Nucleic Acids". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 47 (34): 6330–6337. doi:10.1002/anie.200705982. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 18680110.

- ^ Chen, Xiaoyou; Wang, Bin; Yang, Wen; Kong, Fanrong; Li, Chuanyou; Sun, Zhaogang; Jelfs, Peter; Gilbert, Gwendolyn L. (2014-05-01). "Rolling Circle Amplification for Direct Detection of rpoB Gene Mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates from Clinical Specimens". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 52 (5): 1540–1548. doi:10.1128/JCM.00065-14. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 3993705. PMID 24574296.

- ^ Liu, Yang; Guo, Yan-Ling; Jiang, Guang-Lu; Zhou, Shi-Jie; Sun, Qi; Chen, Xi; Chang, Xiu-Jun; Xing, Ai-Ying; Du, Feng-Jiao (2013-06-04). "Application of Hyperbranched Rolling Circle Amplification for Direct Detection of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis in Clinical Sputum Specimens". PLOS ONE. 8 (6) e64583. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864583L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064583. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3672175. PMID 23750210.

- ^ Guo, Maoxiang; Hernández-Neuta, Iván; Madaboosi, Narayanan; Nilsson, Mats; Wijngaart, Wouter van der (2018-02-12). "Efficient DNA-assisted synthesis of trans-membrane gold nanowires". Microsystems & Nanoengineering. 4 17084. doi:10.1038/micronano.2017.84. ISSN 2055-7434.

External links

[edit]- DNA replication systems used with small circular DNA molecules Genomes 2, T. Brown et al., at NCBI Books

- MicrobiologyBytes: Viroids and Virusoids

- http://mcmanuslab.ucsf.edu/node/246