Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tyrosine

View on Wikipedia

Skeletal formula of L-tyrosine

| |||

L-Tyrosine at physiological pH

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Tyrosine

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

2-Amino-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propanoic acid | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.419 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C9H11NO3 | |||

| Molar mass | 181.191 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | white solid | ||

| 45.3 mg/100 mL | |||

| −105.3·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Tyrosine (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

L-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y)[2] or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a conditionally essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the Greek tyrós, meaning cheese, as it was first discovered in 1846 by German chemist Justus von Liebig in the protein casein from cheese.[3][4] It is called tyrosyl when referred to as a functional group or side chain. While tyrosine is generally classified as a hydrophobic amino acid, it is more hydrophilic than phenylalanine.[5] It is encoded by the codons UAC and UAU in messenger RNA.

The one-letter symbol Y was assigned to tyrosine for being alphabetically nearest of those letters available. Note that T was assigned to the structurally simpler threonine, U was avoided for its similarity with V for valine, W was assigned to tryptophan, while X was reserved for undetermined or atypical amino acids.[6] The mnemonic tYrosine was also proposed.[7]

Functions

[edit]Aside from being a proteinogenic amino acid, tyrosine has a special role by virtue of the phenol functionality. Its hydroxy group is able to form the ester linkage, with phosphate in particular. Phosphate groups are transferred to tyrosine residues by way of protein kinases. This is one of the post-translational modifications. Phosphorylated tyrosine occurs in proteins that are part of signal transduction processes.

Similar functionality is also presented in serine and threonine, whose side chains have a hydroxy group, but are alcohols. Phosphorylation of these three amino acids' moieties (including tyrosine) creates a negative charge on their ends, which is greater than the negative charge of the only negatively charged aspartic and glutamic acids. Phosphorylated proteins keep these same properties—which are useful for more reliable protein-protein interactions—by means of phosphotyrosine, phosphoserine and phosphothreonine.[8]

Binding sites for a signalling phosphoprotein may be diverse in their chemical structure.[9]

Phosphorylation of the hydroxyl group can change the activity of the target protein, or may form part of a signaling cascade via SH2 domain binding.[10]

A tyrosine residue also plays an important role in photosynthesis. In chloroplasts (photosystem II), it acts as an electron donor in the reduction of oxidized chlorophyll. In this process, it loses the hydrogen atom of its phenolic OH-group. This radical is subsequently reduced in the photosystem II by the four core manganese clusters.[11]

Dietary requirements and sources

[edit]The Dietary Reference Intake for tyrosine is usually estimated together with phenylalanine. It varies depending on an estimate method, however the ideal proportion of these two amino acids is considered to be 60:40 (phenylalanine:tyrosine) as a human body has such composition.[12] Tyrosine, which can also be synthesized in the body from phenylalanine, is found in many high-protein food products such as meat, fish, cheese, cottage cheese, milk, yogurt, peanuts, almonds, pumpkin seeds, sesame seeds, soy protein and lima beans.[13][14] For example, the white of an egg has about 250 mg per egg,[15] while beef, lamb, pork, tuna, salmon, chicken, and turkey contain about 500–1000 mg per 3 ounces (85 g) portion.[15][16]

Biosynthesis

[edit]

In plants and most microorganisms, tyrosine is produced via prephenate, an intermediate on the shikimate pathway. Prephenate is oxidatively decarboxylated with retention of the hydroxyl group to give p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate, which is transaminated using glutamate as the nitrogen source to give tyrosine and α-ketoglutarate.

Mammals synthesize tyrosine from the essential amino acid phenylalanine (Phe), which is derived from food. The conversion of Phe to Tyr is catalyzed by the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase, a monooxygenase. This enzyme catalyzes the reaction causing the addition of a hydroxyl group to the end of the 6-carbon aromatic ring of phenylalanine, such that it becomes tyrosine.

Metabolism

[edit]

Phosphorylation and sulfation

[edit]Some of the tyrosine residues can be tagged (at the hydroxyl group) with a phosphate group (phosphorylated) by protein kinases. In its phosphorylated form, tyrosine is called phosphotyrosine. Tyrosine phosphorylation is considered to be one of the key steps in signal transduction and regulation of enzymatic activity. Phosphotyrosine can be detected through specific antibodies. Tyrosine residues may also be modified by the addition of a sulfate group, a process known as tyrosine sulfation.[17] Tyrosine sulfation is catalyzed by tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase (TPST). Like the phosphotyrosine antibodies mentioned above, antibodies have recently been described that specifically detect sulfotyrosine.[18]

Precursor to neurotransmitters and hormones

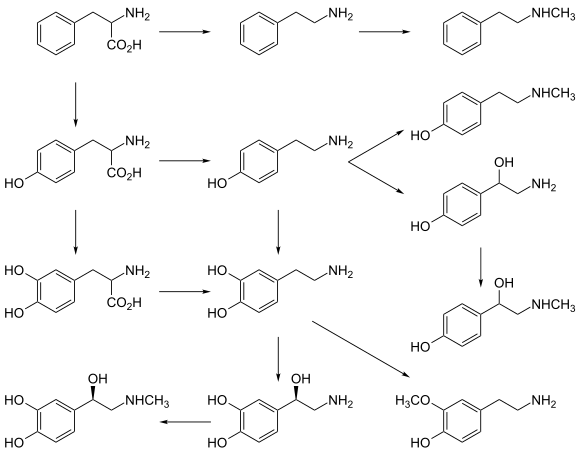

[edit]In dopaminergic cells in the brain, tyrosine is converted to L-DOPA by the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). TH is the rate-limiting enzyme involved in the synthesis of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Dopamine can then be converted into other catecholamines, such as norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and epinephrine (adrenaline).

The thyroid hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) in the colloid of the thyroid are also derived from tyrosine.

Precursor to other compounds

[edit]The latex of Papaver somniferum, the opium poppy, has been shown to convert tyrosine into the alkaloid morphine and the bio-synthetic pathway has been established from tyrosine to morphine by using Carbon-14 radio-labelled tyrosine to trace the in-vivo synthetic route.[22]Tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL) is an enzyme in the natural phenols biosynthesis pathway. It transforms L-tyrosine into p-coumaric acid. Tyrosine is also the precursor to the pigment melanin. Tyrosine (or its precursor phenylalanine) is needed to synthesize the benzoquinone structure which forms part of coenzyme Q10.[23][24]

Degradation

[edit]

The decomposition of L-tyrosine (syn. para-hydroxyphenylalanine) begins with an α-ketoglutarate dependent transamination through the tyrosine transaminase to para-hydroxyphenylpyruvate. The positional description para, abbreviated p, mean that the hydroxyl group and side chain on the phenyl ring are across from each other (see the illustration below).

The next oxidation step catalyzes by p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase and splitting off CO2 homogentisate (2,5-dihydroxyphenyl-1-acetate).[25] In order to split the aromatic ring of homogentisate, a further dioxygenase, homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase is required. Thereby, through the incorporation of a further O2 molecule, maleylacetoacetate is created.

Fumarylacetoacetate is created by maleylacetoacetate cis-trans-isomerase through rotation of the carboxyl group created from the hydroxyl group via oxidation. This cis-trans-isomerase contains glutathione as a coenzyme. Fumarylacetoacetate is finally split by the enzyme fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase through the addition of a water molecule.

Thereby fumarate (also a metabolite of the citric acid cycle) and acetoacetate (3-ketobutyroate) are liberated. Acetoacetate is a ketone body, which is activated with succinyl-CoA, and thereafter it can be converted into acetyl-CoA, which in turn can be oxidized by the citric acid cycle or be used for fatty acid synthesis.

Phloretic acid is also a urinary metabolite of tyrosine in rats.[26]

Ortho- and meta-tyrosine

[edit]

Three structural isomers of L-tyrosine are known. In addition to the common amino acid L-tyrosine, which is the para isomer (para-tyr, p-tyr or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine), there are two additional regioisomers, namely meta-tyrosine (also known as 3-hydroxyphenylalanine, L-m-tyrosine, and m-tyr) and ortho-tyrosine (o-tyr or 2-hydroxyphenylalanine), that occur in nature. The m-tyr and o-tyr isomers, which are rare, arise through non-enzymatic free-radical hydroxylation of phenylalanine under conditions of oxidative stress.[27][28]

Medical use

[edit]Tyrosine is a precursor to neurotransmitters and increases plasma neurotransmitter levels (particularly dopamine and norepinephrine),[29] but has little if any effect on mood in normal subjects.[30][31][32]

A 2015 systematic review found that "tyrosine loading acutely counteracts decrements in working memory and information processing that are induced by demanding situational conditions such as extreme weather or cognitive load" and therefore "tyrosine may benefit healthy individuals exposed to demanding situational conditions".[33]

Industrial synthesis

[edit]L-Tyrosine is used in pharmaceuticals, dietary supplements, and food additives. Two methods were formerly used to manufacture L-tyrosine. The first involves the extraction of the desired amino acid from protein hydrolysates using a chemical approach. The second utilizes enzymatic synthesis from phenolics, pyruvate, and ammonia through the use of tyrosine phenol-lyase.[34] Advances in genetic engineering and the advent of industrial fermentation have shifted the synthesis of L-tyrosine to the use of engineered strains of E. coli.[35][34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Frey MN, Koetzle TF, Lehmann MS, Hamilton WC (1973). "Precision neutron diffraction structure determination of protein and nucleic acid components. X. A comparison between the crystal and molecular structures of L-tyrosine and L-tyrosine hydrochloride". J. Chem. Phys. 58 (6): 2547–2556. Bibcode:1973JChPh..58.2547F. doi:10.1063/1.1679537.

- ^ "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. 1983. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ "Tyrosine". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Infoplease.com — Columbia University Press. 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ^ Harper D (2001). "Tyrosine". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ^ "Amino Acids - Tyrosine". www.biology.arizona.edu. Retrieved 2018-01-31.

- ^ "IUPAC-IUB Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature A One-Letter Notation for Amino Acid Sequences". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 243 (13): 3557–3559. 10 July 1968. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)34176-6.

- ^ Saffran M (April 1998). "Amino acid names and parlor games: from trivial names to a one-letter code, amino acid names have strained students' memories. Is a more rational nomenclature possible?". Biochemical Education. 26 (2): 116–118. doi:10.1016/S0307-4412(97)00167-2.

- ^ Hunter T (2012-09-19). "Why nature chose phosphate to modify proteins". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 367 (1602): 2513–2516. doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0013. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 3415839. PMID 22889903.

- ^ Lu ZC, Jiang F, Wu YD (2021-12-11). "Phosphate binding sites prediction in phosphorylation-dependent protein-protein interactions". Bioinformatics. 37 (24): 4712–4718. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btab525. ISSN 1367-4811. PMID 34270697.

- ^ Liu BA, Nash PD (2012-09-19). "Evolution of SH2 domains and phosphotyrosine signalling networks". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 367 (1602): 2556–2573. doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0107. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 3415846. PMID 22889907.

- ^ Barry BA (January 2015). "Reaction dynamics and proton coupled electron transfer: studies of tyrosine-based charge transfer in natural and biomimetic systems". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1847 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.09.003. ISSN 0006-3002. PMID 25260243.

- ^ Pencharz PB, Hsu JW, Ball RO (June 2007). "Aromatic amino acid requirements in healthy human subjects". The Journal of Nutrition. 137 (6 Suppl 1): 1576S – 1578S, discussion 1597S-1598S. doi:10.1093/jn/137.6.1576S. PMID 17513429.

- ^ Nutient Ranking Tool. MyFoodData.com. https://tools.myfooddata.com/nutrient-ranking-tool/tyrosine/all/highest

- ^ "Tyrosine". University of Maryland Medical Center. Archived from the original on 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- ^ a b Top 10 Foods Highest in Tyrosine

- ^ Nutient Ranking Tool. MyFoodData.com. https://tools.myfooddata.com https://tools.myfooddata.com/nutrient-ranking-tool/tyrosine/meats/highest/ounces/common/no

- ^ Hoffhines AJ, Damoc E, Bridges KG, Leary JA, Moore KL (December 2006). "Detection and purification of tyrosine-sulfated proteins using a novel anti-sulfotyrosine monoclonal antibody". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (49): 37877–87. doi:10.1074/jbc.M609398200. PMC 1764208. PMID 17046811.

- ^ Kanan Y, Hamilton RA, Sherry DM, Al-Ubaidi MR (December 2012). "Focus on molecules: sulfotyrosine". Experimental Eye Research. 105: 85–6. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2012.02.014. PMC 3629733. PMID 22406006.

- ^ Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- ^ Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- ^ Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). "The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D". European Journal of Pharmacology. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- ^ Battersby AR, Binks R, Harper BJ (1962-01-01). "692. Alkaloid biosynthesis. Part II. The biosynthesis of morphine". Journal of the Chemical Society: 3534–3544. doi:10.1039/JR9620003534. ISSN 0368-1769.

- ^ Bentinger M, Tekle M, Dallner G (May 2010). "Coenzyme Q--biosynthesis and functions". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 396 (1): 74–9. Bibcode:2010BBRC..396...74B. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.147. PMID 20494114.

- ^ Acosta MJ, Vazquez Fonseca L, Desbats MA, Cerqua C, Zordan R, Trevisson E, et al. (2016). "Coenzyme Q biosynthesis in health and disease". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1857 (8): 1079–1085. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.036. PMID 27060254.

- ^ Zea-Rey AV, Cruz-Camino H, Vazquez-Cantu DL, Gutiérrez-García VM, Santos-Guzmán J, Cantú-Reyna C (27 November 2017). "The Incidence of Transient Neonatal Tyrosinemia Within a Mexican Population". Journal of Inborn Errors of Metabolism and Screening. 5: 232640981774423. doi:10.1177/2326409817744230.

- ^ Booth AN, Masri MS, Robbins DJ, Emerson OH, Jones FT, DeEds F (1960). "Urinary phenolic acid metabolities of tyrosine". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 235 (9): 2649–2652. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)76930-0.

- ^ Molnár GA, Wagner Z, Markó L, Kó Szegi T, Mohás M, Kocsis B, et al. (November 2005). "Urinary ortho-tyrosine excretion in diabetes mellitus and renal failure: evidence for hydroxyl radical production". Kidney International. 68 (5): 2281–7. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00687.x. PMID 16221230.

- ^ Molnár GA, Nemes V, Biró Z, Ludány A, Wagner Z, Wittmann I (December 2005). "Accumulation of the hydroxyl free radical markers meta-, ortho-tyrosine and DOPA in cataractous lenses is accompanied by a lower protein and phenylalanine content of the water-soluble phase". Free Radical Research. 39 (12): 1359–66. doi:10.1080/10715760500307107. PMID 16298866. S2CID 31154432.

- ^ Rasmussen DD, Ishizuka B, Quigley ME, Yen SS (October 1983). "Effects of tyrosine and tryptophan ingestion on plasma catecholamine and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid concentrations". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 57 (4): 760–3. doi:10.1210/jcem-57-4-760. PMID 6885965.

- ^ Leathwood PD, Pollet P (1982). "Diet-induced mood changes in normal populations". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 17 (2): 147–54. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(82)90016-4. PMID 6764931.

- ^ Deijen JB, Orlebeke JF (1994). "Effect of tyrosine on cognitive function and blood pressure under stress". Brain Research Bulletin. 33 (3): 319–23. doi:10.1016/0361-9230(94)90200-3. PMID 8293316. S2CID 33823121.

- ^ Lieberman HR, Corkin S, Spring BJ, Wurtman RJ, Growdon JH (August 1985). "The effects of dietary neurotransmitter precursors on human behavior". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 42 (2): 366–70. doi:10.1093/ajcn/42.2.366. PMID 4025206.

- ^ Jung SE, Hase A, ann het Rot M (2015). "Behavioral and cognitive effects of tyrosine intake in healthy human adults". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 133: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2015.03.008. PMID 25797188. S2CID 30331663.

- ^ a b Lütke-Eversloh T, Santos CN, Stephanopoulos G (December 2007). "Perspectives of biotechnological production of L-tyrosine and its applications". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 77 (4): 751–62. doi:10.1007/s00253-007-1243-y. PMID 17968539. S2CID 23088822.

- ^ Chavez-Bejar M, Baez-Viveros J, Martinez A, Bolivar F, Gosset G (2012). "Biotechnological production of L-tyrosine and derived compounds". Process Biochemistry. 47 (7): 1017–1026. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2012.04.005.

External links

[edit]Tyrosine

View on GrokipediaChemical Properties

Structure and Nomenclature

Tyrosine is an α-amino acid with the molecular formula C₉H₁₁NO₃.[1] Its structure consists of a central chiral α-carbon atom bonded to an amino group (-NH₂), a carboxyl group (-COOH), a hydrogen atom, and a side chain known as the R-group. The R-group is a 4-hydroxybenzyl moiety, which features a phenyl ring with a hydroxyl (-OH) group attached at the para position, connected via a methylene (-CH₂-) bridge to the α-carbon, effectively forming a modified alanine backbone with an aromatic phenolic substituent.[3][7] The systematic IUPAC name for the naturally occurring form is (2S)-2-amino-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propanoic acid.[7] In biochemical contexts, tyrosine is commonly abbreviated as Tyr (three-letter code) or Y (one-letter code) when representing its residue in protein sequences.[8] The compound is also referred to as L-tyrosine to specify its enantiomeric configuration, distinguishing it from the synthetic D-tyrosine.[1] Tyrosine was first isolated in 1846 from the milk protein casein by German chemist Justus von Liebig through alkaline hydrolysis.[5] The name "tyrosine" derives from the Greek word tyros, meaning cheese, reflecting its origin in dairy-derived casein.[9] Regarding stereochemistry, the biologically relevant enantiomer is L-tyrosine, which has the (S) configuration at the α-carbon according to the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog priority rules.[1] This L-form exhibits levorotatory optical activity, with a specific rotation of [α]_D^{22} = -10.6° (measured in a 4% solution in 1 N HCl).[1] The D-enantiomer, with (R) configuration, is not utilized in standard protein biosynthesis and shows opposite optical rotation.[10]Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Tyrosine appears as a white crystalline solid or powder, odorless and stable under normal conditions.[11] It has a melting point of approximately 343 °C, at which it decomposes without boiling.[12] Solubility in water is low, approximately 0.45 g/L (or 0.45 mg/mL) at 25 °C, though it increases in alkaline solutions; it is insoluble in nonpolar solvents like ethanol, ether, and acetone.[12][5] Chemically, tyrosine is an α-amino acid with three ionizable groups, exhibiting pKa values of 2.20 for the carboxyl group, 9.11 for the amino group, and 10.07 for the phenolic hydroxyl group on its aromatic side chain.[12] At physiological pH (around 7), it exists predominantly as a zwitterion with the carboxyl and amino groups ionized, while the phenolic group remains protonated.[12] The aromatic side chain enables strong ultraviolet absorbance at 274 nm with a molar extinction coefficient of 1405 M⁻¹ cm⁻¹ in phosphate buffer (pH 7), useful for spectrophotometric detection.[13] The polar hydroxyl group facilitates hydrogen bonding, contributing to its reactivity in chemical and biochemical contexts.[3] Tyrosine demonstrates sensitivity to oxidation, particularly under alkaline conditions or in the presence of metal ions and oxidants like hydrogen peroxide, leading to products such as dopaquinone.[14] This reactivity arises from the phenolic moiety, which can undergo one-electron oxidation to form a tyrosyl radical.[15] For identification, tyrosine's spectroscopic characteristics include ¹H NMR signals for the aromatic protons at approximately 6.8–7.2 ppm (doublets) in D₂O, the methylene protons at 2.9–3.1 ppm (doublet of doublets), and the methine proton at 4.0 ppm (triplet); the ¹³C NMR shows the phenolic carbon at around 155 ppm and aromatic carbons between 115–130 ppm.[16] Infrared spectroscopy reveals key absorption bands at 3300–3500 cm⁻¹ (O-H and N-H stretching), 1600–1700 cm⁻¹ (C=O stretch), and 1400–1500 cm⁻¹ (aromatic C=C).[17]Biological Role

Functions in Proteins

Tyrosine is one of the 20 standard amino acids encoded by the genetic code, specifically by the codons UAU and UAC, and is incorporated into polypeptide chains during protein synthesis.[1] In the human proteome, tyrosine accounts for approximately 3.2% of all amino acid residues, reflecting its moderate abundance across diverse protein types.[18] The hydrophilic side chain of tyrosine, consisting of a benzyl ring with a para-hydroxyl group, plays a key role in protein structure by forming hydrogen bonds that promote proper folding and enhance thermodynamic stability.[19] These hydrogen bonds, often involving the phenolic hydroxyl, contribute favorably to overall protein integrity, even in the absence of direct intramolecular pairing with other residues.[20] The aromatic ring further enables pi-stacking interactions with other aromatic amino acids like phenylalanine and tryptophan, which help stabilize secondary and tertiary structures through non-covalent stacking of electron clouds.[21] Tyrosine's phenolic moiety also facilitates coordination with metal ions via its oxygen atom, particularly when deprotonated to form a phenolate, which is essential for catalytic functions in metalloproteins.[22] In enzyme active sites, tyrosine residues often position the hydroxyl group to act as a nucleophile or hydrogen bond donor/acceptor for substrate binding; a notable example is Tyr122 in the A subunit of Escherichia coli DNA gyrase, which forms a transient covalent phosphotyrosyl-DNA intermediate during strand breakage and rejoining.[23] In structural proteins such as collagen and elastin, tyrosine supports cross-linking potential through its reactive phenol group, contributing to the mechanical strength and elasticity of extracellular matrices.[24] Beyond these static roles, tyrosine residues in proteins like receptor tyrosine kinases serve as sites for post-translational phosphorylation, enabling dynamic signaling cascades, though such modifications are addressed separately.[25]Post-Translational Modifications

Tyrosine residues in proteins undergo several key post-translational modifications (PTMs) that leverage the reactivity of their phenolic hydroxyl group, enabling dynamic regulation of protein function, particularly in cellular signaling and interactions. These modifications include phosphorylation, sulfation, nitration, and halogenation, each catalyzed by specific enzymes or reactive species and occurring in distinct cellular contexts.[26] Phosphorylation is the most extensively studied PTM of tyrosine, involving the covalent addition of a phosphate group to the hydroxyl oxygen by protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs), such as the non-receptor kinase Src. This reversible modification is central to signal transduction, where it creates docking sites for downstream effectors containing SH2 or PTB domains, thereby propagating signals from cell surface receptors to intracellular pathways. The reaction is catalyzed as follows: Dephosphorylation by protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) ensures tight temporal control.[26][27] Tyrosine sulfation, mediated by tyrosylprotein sulfotransferases (TPSTs) in the trans-Golgi network of the secretory pathway, introduces a sulfate group to the hydroxyl oxygen using 3'-phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphosulfate (PAPS) as the donor. This modification enhances protein-protein interactions, such as those between chemokines and their receptors or in coagulation factors, influencing processes like immune response and hemostasis. Sulfation occurs on secreted or membrane proteins and is irreversible, with TPST-1 and TPST-2 exhibiting distinct substrate preferences.[28][29] Nitration of tyrosine forms 3-nitrotyrosine through the reaction of the phenolic ring with peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻), a potent oxidant generated from superoxide and nitric oxide under conditions of oxidative stress. This non-enzymatic modification serves as a biomarker for nitro-oxidative damage in diseases like inflammation, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular disorders, as it impairs protein function by altering tyrosine's hydrogen bonding and phosphorylation potential. Detection of elevated 3-nitrotyrosine levels in tissues correlates with peroxynitrite-mediated pathology.[30][31] Halogenation, specifically iodination, targets tyrosine residues in thyroglobulin within thyroid follicular cells, where thyroid peroxidase catalyzes the addition of iodine atoms to form mono- and diiodotyrosine, which then couple to produce thyroid hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4). This modification is essential for hormone synthesis, regulated by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and occurs in the colloid of the thyroid gland. Deficiencies in iodination lead to hypothyroidism.[32][33] These PTMs collectively regulate critical signaling cascades, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, where tyrosine phosphorylation on receptor tyrosine kinases initiates ERK, JNK, and p38 activation in response to growth factors. In eukaryotes, approximately 2% of phosphorylation events target tyrosine residues, underscoring its specificity despite lower abundance compared to serine/threonine sites. Dysregulation of these modifications contributes to oncogenesis, immune disorders, and metabolic diseases.[34][35]Nutrition and Sources

Dietary Requirements

Tyrosine is classified as a non-essential amino acid in humans, as it can be endogenously synthesized from the essential amino acid phenylalanine via the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase. However, it becomes conditionally essential during periods of physiological stress, such as illness or trauma, when synthesis may not meet demands, or in cases of phenylalanine deficiency from low-protein diets. It is also essential for individuals with phenylketonuria (PKU), a genetic disorder impairing phenylalanine hydroxylation, necessitating dietary tyrosine supplementation to prevent neurological complications.[36][37][38] When phenylalanine intake is adequate, the estimated average requirement for tyrosine is approximately 6 mg per kg of body weight per day for healthy adults, ensuring provision for protein synthesis and neurotransmitter production. When considered together with phenylalanine, the combined requirement is 25 mg per kg of body weight per day or 30 mg per g of dietary protein, aligning with patterns for optimal protein quality as per the 2007 WHO/FAO/UNU report. These values derive from indicator amino acid oxidation studies balancing nitrogen retention and metabolic needs. For infants and children, requirements scale with growth rates, while pregnant individuals may need up to 36 mg/kg/day combined to support fetal development.[39][40][41][42] Dietary tyrosine is absorbed primarily in the small intestine through neutral amino acid transporters, notably LAT1 (SLC7A5), a sodium-independent exchanger in the system L family that handles large neutral amino acids. This process is competitive; elevated levels of competing substrates like leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, or valine can inhibit tyrosine uptake, potentially affecting bioavailability during high-protein meals. Once absorbed, tyrosine enters the portal circulation for distribution to tissues.[43][44] True tyrosine deficiency is rare in well-nourished populations due to its synthesis from phenylalanine but can arise from chronic low-protein intake or unmanaged PKU, leading to symptoms such as fatigue, depressed mood, and irritability. These effects stem from reduced production of catecholamine neurotransmitters like dopamine and norepinephrine, which rely on tyrosine as a precursor and influence arousal, motivation, and stress response. In severe cases, prolonged deficiency may exacerbate cognitive impairments.[45][46] The World Health Organization/Food and Agriculture Organization (WHO/FAO) standards, last comprehensively updated in 2013 with ongoing refinements through 2023 expert consultations, maintain the combined phenylalanine + tyrosine requirement at 30 mg/g protein for adults but highlight elevated tyrosine needs in PKU patients—typically 40–120 mg/kg/day depending on age—to compensate for restricted phenylalanine and support neurometabolic balance. These guidelines emphasize monitoring plasma levels to avoid both deficiency and excess, which could lead to hyperphenylalaninemia.[47][41][48]Food Sources

Foods rich in tyrosine, such as eggs, chicken, almonds, bananas, avocados, beans, and dark chocolate, provide dietary tyrosine that supports its role as a precursor to neurotransmitters like dopamine. Tyrosine is abundant in protein-rich foods, with animal-derived sources generally providing higher concentrations per serving compared to plant-based options. Notable animal sources include dairy products such as Parmesan cheese, which contains approximately 2.0 g of tyrosine per 100 g, and eggs, offering about 0.5 g per 100 g. Meats like beef and poultry also contribute significantly, with lean beef providing around 1.2 g per 100 g and chicken breast approximately 1.1 g per 100 g.[49][50][51] Plant-based foods serve as viable sources, particularly for vegetarians and vegans, though they often require larger portions to match animal-derived intake levels. Soy products stand out, with roasted soybeans delivering about 1.8 g per 100 g and tofu around 0.8 g per 100 g. Seeds and nuts are also rich; for instance, pumpkin seeds contain roughly 1.2 g per 100 g, while sesame seeds provide 0.9 g per 100 g. Legumes like lentils and beans offer 0.6–0.7 g per 100 g, and whole grains such as quinoa contribute about 0.5 g per 100 g.[49][50][52][53]| Food Category | Example | Tyrosine Content (g/100 g) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy | Parmesan cheese | 2.0 | USDA FoodData Central[49] |

| Eggs | Whole egg, cooked | 0.5 | USDA FoodData Central[49] |

| Meat/Poultry | Lean beef | 1.2 | USDA FoodData Central[49] |

| Legumes | Roasted soybeans | 1.8 | USDA FoodData Central[49] |

| Seeds | Pumpkin seeds | 1.2 | USDA FoodData Central[49] |