Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Satellite (biology).

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Satellite (biology)

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Satellite (biology)

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

In biology, a satellite is a subviral agent composed of nucleic acid that relies on the co-infection of a host cell with a helper virus for its replication and propagation, lacking the genes necessary to independently encode essential replication functions.[1] These entities are genetically distinct from their helper viruses, often sharing only short identical nucleotide sequences. Although historically not assigned formal taxonomic classifications by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) and grouped by their genetic material type, such as RNA or DNA, recent updates as of 2025 have established families for many satellites, including Tonesaviridae for certain plant satellite viruses and Alphasatellitidae for alphasatellites.[1][2][3]

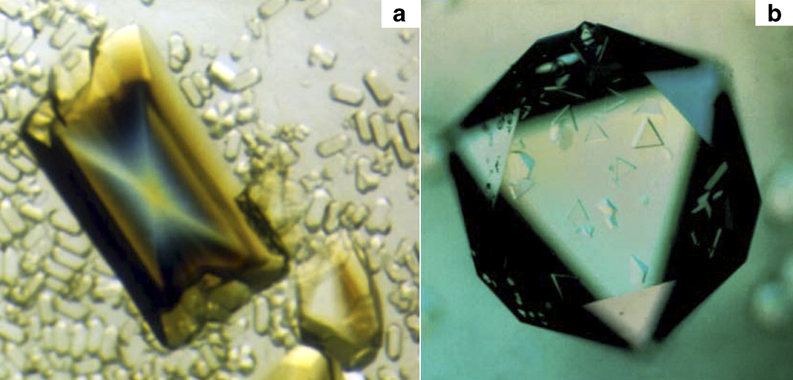

Satellites are broadly divided into two categories: satellite viruses, which encode their own structural proteins like capsid components to form independent virions, and satellite nucleic acids, which do not produce such proteins and are instead encapsidated by the helper virus's coat. Examples of satellite viruses include the Tobacco necrosis satellite virus (STNV), which depends on the Tobacco necrosis virus (TNV) as a helper and was the first identified in 1962, and the Sputnik virophage, a double-stranded DNA satellite that parasitizes mimiviruses in amoebae.[4] Satellite nucleic acids encompass diverse forms, such as betasatellites and alphasatellites associated with plant geminiviruses, which are single-stranded DNA molecules that modulate disease symptoms in crops like cotton and tomatoes.[1]

A key feature of satellites is their ability to influence the biology of their helper viruses, often attenuating or exacerbating symptoms in the host organism; for instance, certain satellite RNAs of plant viruses can reduce disease severity, providing potential applications in viral control strategies. While most satellites infect plants or protists, recent discoveries include RNA satellites in mammals, such as those linked to hepatitis D virus (HDV), highlighting their evolutionary diversity and role in viral ecosystems.[5] Unlike autonomous viruses, satellites cannot replicate alone and represent an evolutionary intermediate between viruses and other subviral agents like viroids, underscoring their significance in understanding viral dependency and host-virus interactions.[1]