Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Virus

View on Wikipedia

| Virus | |

|---|---|

| |

| SARS-CoV-2, a member of the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realms | |

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism.[1] Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.[2][3] Viruses are found in almost every ecosystem on Earth and are the most numerous type of biological entity.[4][5] Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1892 article describing a non-bacterial pathogen infecting tobacco plants and the discovery of the tobacco mosaic virus by Martinus Beijerinck in 1898,[6]: 4 more than 16,000 of the millions of virus species have been described in detail.[7][8] The study of viruses is known as virology, a subspeciality of microbiology.

When infected, a host cell is often forced to rapidly produce thousands of copies of the original virus. When not inside an infected cell or in the process of infecting a cell, viruses exist in the form of independent viral particles, or virions, consisting of (i) genetic material, i.e., long molecules of DNA or RNA that encode the structure of the proteins by which the virus acts; (ii) a protein coat, the capsid, which surrounds and protects the genetic material; and in some cases (iii) an outside envelope of lipids. The shapes of these virus particles range from simple helical and icosahedral forms to more complex structures. Most virus species have virions too small to be seen with an optical microscope and are one-hundredth the size of most bacteria.

The origins of viruses in the evolutionary history of life are still unclear. Some viruses may have evolved from plasmids, which are pieces of DNA that can move between cells. Other viruses may have evolved from bacteria. In evolution, viruses are an important means of horizontal gene transfer, which increases genetic diversity in a way analogous to sexual reproduction.[9] Viruses are considered by some biologists to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce, and evolve through natural selection, although they lack some key characteristics, such as cell structure, that are generally considered necessary criteria for defining life. Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as "organisms at the edge of life"[10] and as replicators.[11]

Viruses spread in many ways. One transmission pathway is through disease-bearing organisms known as vectors: for example, viruses are often transmitted from plant to plant by insects that feed on plant sap, such as aphids; and viruses in animals can be carried by blood-sucking insects. Many viruses spread in the air by coughing and sneezing, including influenza viruses, SARS-CoV-2, chickenpox, smallpox, and measles. Norovirus and rotavirus, common causes of viral gastroenteritis, are transmitted by the faecal–oral route, passed by hand-to-mouth contact or in food or water. The infectious dose of norovirus required to produce infection in humans is fewer than 100 particles.[12] HIV is one of several viruses transmitted through sexual contact and by exposure to infected blood. The variety of host cells that a virus can infect is called its host range: this is narrow for viruses specialized to infect only a few species, or broad for viruses capable of infecting many.[13]: 123–124

Viral infections in animals provoke an immune response that usually eliminates the infecting virus. Immune responses can also be produced by vaccines, which confer an artificially acquired immunity to the specific viral infection. Some viruses, including those that cause HIV/AIDS, HPV infection, and viral hepatitis, evade these immune responses and result in chronic infections. Several classes of antiviral drugs have been developed.

Etymology

[edit]The English word "virus" comes from the Latin word vīrus, which refers to poison and other noxious liquids. Vīrus comes from the same Indo-European root as Sanskrit viṣa, Avestan vīša, and Ancient Greek ἰός (iós), which all mean "poison". The first attested use of "virus" in English appeared in 1398 in John Trevisa's translation of Bartholomeus Anglicus's De Proprietatibus Rerum.[14][15] Virulent, from Latin virulentus ('poisonous'), dates to c. 1400.[16][17] A meaning of 'agent that causes infectious disease' is first recorded in 1728,[15] long before the discovery of viruses by Dmitri Ivanovsky in 1892. The English plural is viruses (sometimes also vira),[18] whereas the Latin word is a mass noun, which has no classically attested plural (vīra is used in Neo-Latin[19]). The adjective viral dates to 1948.[20] The term virion (plural virions), which dates from 1959,[21] is also used to refer to a single viral particle that is released from the cell and is capable of infecting other cells of the same type.[22]

Origins

[edit]Viruses are found wherever there is life and have probably existed since living cells first evolved.[23] The origin of viruses is unclear because they do not form fossils, so molecular techniques are used to infer how they arose.[24] In addition, viral genetic material occasionally integrates into the germline of the host organisms, by which they can be passed on vertically to the offspring of the host for many generations. This provides an invaluable source of information for paleovirologists to trace back ancient viruses that existed as far back as millions of years ago.

There are three main hypotheses that aim to explain the origins of viruses:[25]

- Regressive hypothesis

- Viruses may have once been small cells that parasitised larger cells. Over time, genes not required by their parasitism were lost. The bacteria rickettsia and chlamydia are living cells that, like viruses, can reproduce only inside host cells. They lend support to this hypothesis, as their dependence on parasitism is likely to have caused the loss of genes that enabled them to survive outside a cell. This is also called the "degeneracy hypothesis",[6]: 16 [26]: 11 or "reduction hypothesis".[27]: 24

- Cellular origin hypothesis

- Some viruses may have evolved from bits of DNA or RNA that "escaped" from the genes of a larger organism. The escaped DNA could have come from plasmids (pieces of naked DNA that can move between cells) or transposons (molecules of DNA that replicate and move around to different positions within the genes of the cell).[13]: 810 Once called "jumping genes", transposons are examples of mobile genetic elements and could be the origin of some viruses. They were discovered in maize by Barbara McClintock in 1950.[28] This is sometimes called the "vagrancy hypothesis",[6]: 16 [26]: 11–12 or the "escape hypothesis".[27]: 24

- Co-evolution hypothesis

- This is also called the "virus-first hypothesis"[27]: 24 and proposes that viruses may have evolved from complex molecules of protein and nucleic acid at the same time that cells first appeared on Earth and would have been dependent on cellular life for billions of years. Viroids are molecules of RNA that are not classified as viruses because they lack a protein coat. They have characteristics that are common to several viruses and are often called subviral agents.[6]: 55 Viroids are significant pathogens of plants.[13]: 791 They do not code for proteins but interact with the host cell and use the host machinery for their replication.[29] The hepatitis delta virus of humans has an RNA genome similar to viroids but has a protein coat derived from hepatitis B virus and cannot produce one of its own. It is, therefore, a defective virus. Although hepatitis delta virus genome may replicate independently once inside a host cell, it requires the help of hepatitis B virus to provide a protein coat so that it can be transmitted to new cells.[13]: 460 In similar manner, the sputnik virophage is dependent on mimivirus, which infects the protozoan Acanthamoeba castellanii.[30] These viruses, which are dependent on the presence of other virus species in the host cell, are called "satellites" and may represent evolutionary intermediates of viroids and viruses.[26]: 777 [6]: 55–57

In the past, there were problems with all of these hypotheses: the regressive hypothesis did not explain why even the smallest of cellular parasites do not resemble viruses in any way. The escape hypothesis did not explain the complex capsids and other structures on virus particles. The virus-first hypothesis contravened the definition of viruses in that they require host cells.[27]: 24 Viruses are now recognised as ancient and as having origins that pre-date the divergence of life into the three domains.[27]: 28 This discovery has led modern virologists to reconsider and re-evaluate these three classical hypotheses.[27]: 28

The evidence for an ancestral world of RNA cells[27]: 26 and computer analysis of viral and host DNA sequences give a better understanding of the evolutionary relationships between different viruses and may help identify the ancestors of modern viruses. To date, such analyses have not proved which of these hypotheses is correct.[27]: 26 It seems unlikely that all currently known viruses have a common ancestor, and viruses have probably arisen numerous times in the past by one or more mechanisms.[31]

Microbiology

[edit]Discovery

[edit]The first evidence of the existence of viruses came from experiments with filters that had pores small enough to retain bacteria. In 1892, Dmitri Ivanovsky used one of these filters to show that sap from a diseased tobacco plant remained infectious to healthy tobacco plants despite having been filtered. Martinus Beijerinck called the filtered, infectious substance a "virus" and this discovery is considered to be the beginning of virology. The subsequent discovery and partial characterization of bacteriophages by Frederick Twort and Félix d'Herelle further catalyzed the field, and by the early 20th century many viruses had been discovered. In 1926, Thomas Milton Rivers defined viruses as obligate parasites. Viruses were demonstrated to be particles, rather than a fluid, by Wendell Meredith Stanley, and the invention of the electron microscope in 1931 allowed their complex structures to be visualised.[32]

Life properties

[edit]Scientific opinions differ on whether viruses are a form of life or organic structures that interact with living organisms.[11] They have been described as "organisms at the edge of life",[10] since they resemble organisms in that they possess genes, evolve by natural selection,[33] and reproduce by creating multiple copies of themselves through self-assembly. Although they have genes, they do not have a cellular structure, which is often seen as the basic unit of life. Viruses do not have their own metabolism and require a host cell to make new products. They therefore cannot naturally reproduce outside a host cell[34]—although some bacteria such as rickettsia and chlamydia are considered living organisms despite the same limitation.[35][36] Accepted forms of life use cell division to reproduce, whereas viruses spontaneously assemble within cells. They differ from autonomous growth of crystals as they inherit genetic mutations while being subject to natural selection. Virus self-assembly within host cells has implications for the study of the origin of life, as it lends further credence to the hypothesis that life could have started as self-assembling organic molecules.[2] The virocell model first proposed by Patrick Forterre considers the infected cell to be the "living form" of viruses and that virus particles (virions) are analogous to spores.[37] Although the living versus non-living debate continues, the virocell model has gained some acceptance.[38]

Structure

[edit]Viruses display a wide diversity of sizes and shapes, called 'morphologies'. In general, viruses are much smaller than bacteria and more than a thousand bacteriophage viruses would fit inside an Escherichia coli bacterium's cell.[39]: 98 Many viruses that have been studied are spherical and have a diameter between 20 and 300 nanometres. Some filoviruses, which are filaments, have a total length of up to 1400 nm; their diameters are only about 80 nm.[26]: 33–55 Most viruses cannot be seen with an optical microscope, so scanning and transmission electron microscopes are used to visualise them.[26]: 33–37 To increase the contrast between viruses and the background, electron-dense "stains" are used. These are solutions of salts of heavy metals, such as tungsten, that scatter the electrons from regions covered with the stain. When virions are coated with stain (positive staining), fine detail is obscured. Negative staining overcomes this problem by staining the background only.[40]

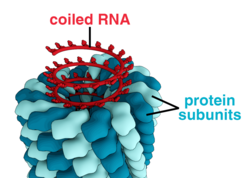

A complete virus particle, known as a virion, consists of nucleic acid surrounded by a protective coat of protein called a capsid. These are formed from protein subunits called capsomeres.[26]: 40 Viruses can have a lipid "envelope" derived from the host cell membrane. The capsid is made from proteins encoded by the viral genome and its shape serves as the basis for morphological distinction.[41][42] Virally-coded protein subunits will self-assemble to form a capsid, in general requiring the presence of the virus genome. Complex viruses code for proteins that assist in the construction of their capsid. Proteins associated with nucleic acid are known as nucleoproteins, and the association of viral capsid proteins with viral nucleic acid is called a nucleocapsid. The capsid and entire virus structure can be mechanically (physically) probed through atomic force microscopy.[43][44] In general, there are five main morphological virus types:

- Helical

- These viruses are composed of a single type of capsomere stacked around a central axis to form a helical structure, which may have a central cavity, or tube. This arrangement results in virions which can be short and highly rigid rods, or long and very flexible filaments. The genetic material (typically single-stranded RNA, but single-stranded DNA in some cases) is bound into the protein helix by interactions between the negatively charged nucleic acid and positive charges on the protein. Overall, the length of a helical capsid is related to the length of the nucleic acid contained within it, and the diameter is dependent on the size and arrangement of capsomeres. The well-studied tobacco mosaic virus[26]: 37 and inovirus[45] are examples of helical viruses.

- Icosahedral

- Most animal viruses are icosahedral or near-spherical with chiral icosahedral symmetry. A regular icosahedron is the optimum way of forming a closed shell from identical subunits. The minimum number of capsomeres required for each triangular face is 3, which gives 60 for the icosahedron. Many viruses, such as rotavirus, have more than 60 capsomers and appear spherical but they retain this symmetry. To achieve this, the capsomeres at the apices are surrounded by five other capsomeres and are called pentons. Capsomeres on the triangular faces are surrounded by six others and are called hexons.[26]: 40, 42 Hexons are in essence flat and pentons, which form the 12 vertices, are curved. The same protein may act as the subunit of both the pentamers and hexamers or they may be composed of different proteins.[46]

- Prolate

- This is an icosahedron elongated along the fivefold axis and is a common arrangement of the heads of bacteriophages. This structure is composed of a cylinder with a cap at either end.[47]

- Enveloped

- Some species of virus envelop themselves in a modified form of one of the cell membranes, either the outer membrane surrounding an infected host cell or internal membranes such as a nuclear membrane or endoplasmic reticulum, thus gaining an outer lipid bilayer known as a viral envelope. This membrane is studded with proteins coded for by the viral genome and host genome; the lipid membrane itself and any carbohydrates present originate entirely from the host. Influenza virus, HIV (which causes AIDS), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (which causes COVID-19)[48] use this strategy. Most enveloped viruses are dependent on the envelope for their infectivity.[26]: 42–43

- Complex

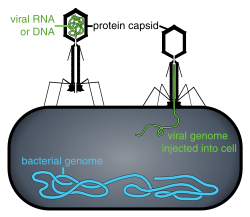

- These viruses possess a capsid that is neither purely helical nor purely icosahedral, and that may possess extra structures such as protein tails or a complex outer wall. Some bacteriophages, such as Enterobacteria phage T4, have a complex structure consisting of an icosahedral head bound to a helical tail, which may have a hexagonal base plate with protruding protein tail fibres. This tail structure acts like a molecular syringe, attaching to the bacterial host and then injecting the viral genome into the cell.[49]

The poxviruses are large, complex viruses that have an unusual morphology. The viral genome is associated with proteins within a central disc structure known as a nucleoid. The nucleoid is surrounded by a membrane and two lateral bodies of unknown function. The virus has an outer envelope with a thick layer of protein studded over its surface. The whole virion is slightly pleomorphic, ranging from ovoid to brick-shaped.[50]

Giant viruses

[edit]Mimivirus is one of the largest characterised viruses, with a capsid diameter of 400 nm. Protein filaments measuring 100 nm project from the surface. The capsid appears hexagonal under an electron microscope, therefore the capsid is probably icosahedral.[51] In 2011, researchers discovered the largest then known virus in samples of water collected from the ocean floor off the coast of Las Cruces, Chile. Provisionally named Megavirus chilensis, it can be seen with a basic optical microscope.[52] In 2013, the Pandoravirus genus was discovered in Chile and Australia, and has genomes about twice as large as Megavirus and Mimivirus.[53] All giant viruses have dsDNA genomes and they are classified into several families: Mimiviridae, Pithoviridae, Pandoraviridae, Phycodnaviridae, and the Mollivirus genus.[54]

Some viruses that infect Archaea have complex structures unrelated to any other form of virus, with a wide variety of unusual shapes, ranging from spindle-shaped structures to viruses that resemble hooked rods, teardrops or even bottles. Other archaeal viruses resemble the tailed bacteriophages, and can have multiple tail structures.[55]

Genome

[edit]| Property | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Nucleic acid |

|

| Shape |

|

| Strandedness |

|

| Sense |

|

An enormous variety of genomic structures can be seen among viral species; as a group, they contain more structural genomic diversity than plants, animals, archaea, or bacteria. There are millions of different types of viruses,[8] although fewer than 7,000 types have been described in detail.[6]: 49 As of January 2021, the NCBI Virus genome database has more than 193,000 complete genome sequences,[56] but there are doubtlessly many more to be discovered.[57][58]

A virus has either a DNA or an RNA genome and is called a DNA virus or an RNA virus, respectively. Some RNA viruses, for example retroviruses, have a stage in their replication cycle where the genome is encoded in DNA.[59] Most viruses have RNA genomes. Plant viruses tend to have single-stranded RNA genomes and bacteriophages tend to have double-stranded DNA genomes.[26]: 96–99

Viral genomes are circular, as in the polyomaviruses, or linear, as in the adenoviruses. The type of nucleic acid is irrelevant to the shape of the genome. Among RNA viruses and certain DNA viruses, the genome is often divided into separate parts, in which case it is called segmented. For RNA viruses, each segment often codes for only one protein and they are usually found together in one capsid. All segments are not required to be in the same virion for the virus to be infectious, as demonstrated by brome mosaic virus and several other plant viruses.[26]: 33–35

A viral genome, irrespective of nucleic acid type, is almost always either single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds). Single-stranded genomes consist of an unpaired nucleic acid, analogous to one-half of a ladder split down the middle. Double-stranded genomes consist of two complementary paired nucleic acids, analogous to a ladder. The virus particles of some virus families, such as those belonging to the Hepadnaviridae, contain a genome that is partially double-stranded and partially single-stranded.[26]: 96–99

For most viruses with RNA genomes and some with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genomes, the single strands are said to be either positive-sense (called the 'plus-strand') or negative-sense (called the 'minus-strand'), depending on if they are complementary to the viral messenger RNA (mRNA). Positive-sense viral RNA is in the same sense as viral mRNA and thus at least a part of it can be immediately translated by the host cell. Negative-sense viral RNA is complementary to mRNA and thus must be converted to positive-sense RNA by an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase before translation. DNA nomenclature for viruses with genomic ssDNA is similar to RNA nomenclature, in that positive-strand viral ssDNA is identical in sequence to the viral mRNA and is thus a coding strand, while negative-sense viral ssDNA is complementary to the viral mRNA and is thus a template strand.[26]: 96–99 Several types of ssDNA and ssRNA viruses have genomes that are ambisense in that transcription can occur off both strands in a double-stranded replicative intermediate. Examples include geminiviruses, which are ssDNA plant viruses and arenaviruses, which are ssRNA viruses of animals.[60]

Genome size

[edit]Genome size varies greatly between species. The smallest—the ssDNA circoviruses, family Circoviridae—code for only two proteins and have a genome size of only two kilobases;[61] the largest—the pandoraviruses—have genome sizes of around two megabases which code for about 2500 proteins.[53] Virus genes rarely have introns and often are arranged in the genome so that they overlap.[62]

In general, RNA viruses have smaller genome sizes than DNA viruses because of a higher error-rate when replicating, and have a maximum upper size limit.[24] Beyond this, errors when replicating render the virus useless or uncompetitive. To compensate, RNA viruses often have segmented genomes—the genome is split into smaller molecules—thus reducing the chance that an error in a single-component genome will incapacitate the entire genome. In contrast, DNA viruses generally have larger genomes because of the high fidelity of their replication enzymes.[63] Single-strand DNA viruses are an exception to this rule, as mutation rates for these genomes can approach the extreme of the ssRNA virus case.[64]

Genetic mutation and recombination

[edit]

Viruses undergo genetic change by several mechanisms. These include a process called antigenic drift where individual bases in the DNA or RNA mutate to other bases. Most of these point mutations are "silent"—they do not change the protein that the gene encodes—but others can confer evolutionary advantages such as resistance to antiviral drugs.[65][66] Antigenic shift occurs when there is a major change in the genome of the virus. This can be a result of recombination or reassortment. The Influenza A virus is highly prone to reassortment; occasionally this has resulted in novel strains which have caused pandemics.[67] RNA viruses often exist as quasispecies or swarms of viruses of the same species but with slightly different genome nucleoside sequences. Such quasispecies are a prime target for natural selection.[68]

Segmented genomes confer evolutionary advantages; different strains of a virus with a segmented genome can shuffle and combine genes and produce progeny viruses (or offspring) that have unique characteristics. This is called reassortment or 'viral sex'.[69]

Genetic recombination is a process by which a strand of DNA (or RNA) is broken and then joined to the end of a different DNA (or RNA) molecule. This can occur when viruses infect cells simultaneously and studies of viral evolution have shown that recombination has been rampant in the species studied.[70] Recombination is common to both RNA and DNA viruses.[71][72]

Coronaviruses have a single-strand positive-sense RNA genome. Replication of the genome is catalyzed by an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. The mechanism of recombination used by coronaviruses likely involves template switching by the polymerase during genome replication.[73] This process appears to be an adaptation for coping with genome damage.[74]

Replication cycle

[edit]

Viral populations do not grow through cell division, because they are acellular. Instead, they use the machinery and metabolism of a host cell to produce multiple copies of themselves, and they assemble in the cell.[75] When infected, the host cell is forced to rapidly produce thousands of copies of the original virus.[76]

Their life cycle differs greatly between species, but there are six basic stages in their life cycle:[26]: 75–91

Attachment is a specific binding between viral capsid proteins and specific receptors on the host cellular surface. This specificity determines the host range and type of host cell of a virus. For example, HIV infects a limited range of human leucocytes. This is because its surface protein, gp120, specifically interacts with the CD4 molecule—a chemokine receptor—which is most commonly found on the surface of CD4+ T-Cells. This mechanism has evolved to favour those viruses that infect only cells in which they are capable of replication. Attachment to the receptor can induce the viral envelope protein to undergo changes that result in the fusion of viral and cellular membranes, or changes of non-enveloped virus surface proteins that allow the virus to enter.[77]

Penetration or viral entry follows attachment: Virions enter the host cell through receptor-mediated endocytosis or membrane fusion. The infection of plant and fungal cells is different from that of animal cells. Plants have a rigid cell wall made of cellulose, and fungi one of chitin, so most viruses can get inside these cells only after trauma to the cell wall.[6]: 70 Nearly all plant viruses (such as tobacco mosaic virus) can also move directly from cell to cell, in the form of single-stranded nucleoprotein complexes, through pores called plasmodesmata.[78] Bacteria, like plants, have strong cell walls that a virus must breach to infect the cell. Given that bacterial cell walls are much thinner than plant cell walls due to their much smaller size, some viruses have evolved mechanisms that inject their genome into the bacterial cell across the cell wall, while the viral capsid remains outside.[6]: 71

Uncoating is a process in which the viral capsid is removed: This may be by degradation by viral enzymes or host enzymes or by simple dissociation; the end-result is the releasing of the viral genomic nucleic acid.[79]

Replication of viruses involves primarily multiplication of the genome. Replication involves the synthesis of viral messenger RNA (mRNA) from "early" genes (with exceptions for positive-sense RNA viruses), viral protein synthesis, possible assembly of viral proteins, then viral genome replication mediated by early or regulatory protein expression. This may be followed, for complex viruses with larger genomes, by one or more further rounds of mRNA synthesis: "late" gene expression is, in general, of structural or virion proteins.[80]

Assembly – Following the structure-mediated self-assembly of the virus particles, some modification of the proteins often occurs. In viruses such as HIV, this modification (sometimes called maturation) occurs after the virus has been released from the host cell.[81]

Release – Viruses can be released from the host cell by lysis, a process that kills the cell by bursting its membrane and cell wall if present: this is a feature of many bacterial and some animal viruses. Some viruses undergo a lysogenic cycle where the viral genome is incorporated by genetic recombination into a specific place in the host's chromosome. The viral genome is then known as a "provirus" or, in the case of bacteriophages a "prophage".[13]: 836 Whenever the host divides, the viral genome is also replicated. The viral genome is mostly silent within the host. At some point, the provirus or prophage may give rise to the active virus, which may lyse the host cells.[6]: 243–259 Enveloped viruses (e.g., HIV) typically are released from the host cell by budding. During this process, the virus acquires its envelope, which is a modified piece of the host's plasma or other, internal membrane.[6]: 185–187

Genome replication

[edit]The genetic material within virus particles, and the method by which the material is replicated, varies considerably between different types of viruses.

- DNA viruses

- The genome replication of most DNA viruses takes place in the cell's nucleus. If the cell has the appropriate receptor on its surface, these viruses enter the cell either by direct fusion with the cell membrane (e.g., herpesviruses) or—more usually—by receptor-mediated endocytosis. Most DNA viruses are entirely dependent on the host cell's DNA and RNA synthesising machinery and RNA processing machinery. Viruses with larger genomes may encode much of this machinery themselves. In eukaryotes, the viral genome must cross the cell's nuclear membrane to access this machinery, while in bacteria it need only enter the cell.[13]: 118 [26]: 78

- RNA viruses

- Replication of RNA viruses usually takes place in the cytoplasm. RNA viruses can be placed into four different groups depending on their modes of replication. The polarity (whether or not it can be used directly by ribosomes to make proteins) of single-stranded RNA viruses largely determines the replicative mechanism; the other major criterion is whether the genetic material is single-stranded or double-stranded. All RNA viruses use their own RNA replicase enzymes to create copies of their genomes.[26]: 79

- Reverse transcribing viruses

- Reverse transcribing viruses have ssRNA (Retroviridae, Metaviridae, Pseudoviridae) or dsDNA (Caulimoviridae, and Hepadnaviridae) in their particles. Reverse transcribing viruses with RNA genomes (retroviruses) use a DNA intermediate to replicate, whereas those with DNA genomes (pararetroviruses) use an RNA intermediate during genome replication. Both types use a reverse transcriptase, or RNA-dependent DNA polymerase enzyme, to carry out the nucleic acid conversion. Retroviruses integrate the DNA produced by reverse transcription into the host genome as a provirus as a part of the replication process; pararetroviruses do not, although integrated genome copies of especially plant pararetroviruses can give rise to infectious virus.[82] They are susceptible to antiviral drugs that inhibit the reverse transcriptase enzyme, e.g. zidovudine and lamivudine. An example of the first type is HIV, which is a retrovirus. Examples of the second type are the Hepadnaviridae, which includes Hepatitis B virus.[26]: 88–89

Cytopathic effects on the host cell

[edit]The range of structural and biochemical effects that viruses have on the host cell is extensive.[26]: 115–146 These are called 'cytopathic effects'.[26]: 115 Most virus infections eventually result in the death of the host cell. The causes of death include cell lysis, alterations to the cell's surface membrane and apoptosis.[83] Often cell death is caused by cessation of its normal activities because of suppression by virus-specific proteins, not all of which are components of the virus particle.[84] The distinction between cytopathic and harmless is gradual. Some viruses, such as Epstein–Barr virus, can cause cells to proliferate without causing malignancy,[85] while others, such as papillomaviruses, are established causes of cancer.[86]

Dormant and latent infections

[edit]Some viruses cause no apparent changes to the infected cell. Cells in which the virus is latent and inactive show few signs of infection and often function normally.[87] This causes persistent infections and the virus is often dormant for many months or years. This is often the case with herpes viruses.[88][89]

Host range

[edit]Viruses are by far the most abundant biological entities on Earth and they outnumber all the others put together.[90] They infect all types of cellular life including animals, plants, bacteria and fungi.[6]: 49 Different types of viruses can infect only a limited range of hosts and many are species-specific. Some, such as smallpox virus for example, can infect only one species—in this case humans,[13]: 643 and are said to have a narrow host range. Other viruses, such as rabies virus, can infect different species of mammals and are said to have a broad range.[13]: 631 The viruses that infect plants are harmless to animals, and most viruses that infect other animals are harmless to humans.[6]: 272 The host range of some bacteriophages is limited to a single strain of bacteria and they can be used to trace the source of outbreaks of infections by a method called phage typing.[91] The complete set of viruses in an organism or habitat is called the virome; for example, all human viruses constitute the human virome.[92]

Novel viruses

[edit]A novel virus is one that has not previously been recorded. It can be a virus that is isolated from its natural reservoir or isolated as the result of spread to an animal or human host where the virus had not been identified before. It can be an emergent virus, one that represents a new virus, but it can also be an extant virus that has not been previously identified.[93] The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic is an example of a novel virus.[94]

Classification

[edit]Classification seeks to describe the diversity of viruses by naming and grouping them on the basis of similarities. In 1962, André Lwoff, Robert Horne, and Paul Tournier were the first to develop a means of virus classification, based on the Linnaean hierarchical system.[95] This system based classification on phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. Viruses were grouped according to their shared properties (not those of their hosts) and the type of nucleic acid forming their genomes.[96] In 1966, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) was formed. The system proposed by Lwoff, Horne and Tournier was initially not accepted by the ICTV because the small genome size of viruses and their high rate of mutation made it difficult to determine their ancestry beyond order. As such, the Baltimore classification system has come to be used to supplement the more traditional hierarchy.[97] Starting in 2018, the ICTV began to acknowledge deeper evolutionary relationships between viruses that have been discovered over time and adopted a 15-rank classification system ranging from realm to species.[98] Additionally, some species within the same genus are grouped into a genogroup.[99][100]

ICTV classification

[edit]The ICTV developed the current classification system and wrote guidelines that put a greater weight on certain virus properties to maintain family uniformity. A unified taxonomy (a universal system for classifying viruses) has been established.[101] Only a small part of the total diversity of viruses has been studied.[102] As of 2024, 7 realms, 11 kingdoms, 22 phyla, 4 subphyla, 49 classes, 93 orders, 12 suborders, 368 families, 213 subfamilies, 3,769 genera, 86 subgenera, and 16,215 species of viruses have been defined by the ICTV.[7]

The general taxonomic structure of taxon ranges and the suffixes used in taxonomic names are shown hereafter. As of 2022, the ranks of subrealm, subkingdom, and subclass are unused, whereas all other ranks are in use.[7]

- Realm (-viria)

Baltimore classification

[edit]

The Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore devised the Baltimore classification system.[103][104] The ICTV classification system is used in conjunction with the Baltimore classification system in modern virus classification.[105][106][107]

The Baltimore classification of viruses is based on the mechanism of mRNA production. Viruses must generate mRNAs from their genomes to produce proteins and replicate themselves, but different mechanisms are used to achieve this in each virus family. Viral genomes may be single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds), RNA or DNA, and may or may not use reverse transcriptase (RT). In addition, ssRNA viruses may be either sense (+) or antisense (−). This classification places viruses into seven groups:

- I: dsDNA viruses (e.g. Adenoviruses, Herpesviruses, Poxviruses)

- II: ssDNA viruses (+ strand or "sense") DNA (e.g. Parvoviruses)

- III: dsRNA viruses (e.g. Reoviruses)

- IV:(+)ssRNA viruses (+ strand or sense) RNA (e.g. Coronaviruses, Picornaviruses, Togaviruses)

- V: (−)ssRNA viruses (− strand or antisense) RNA (e.g. Orthomyxoviruses, Rhabdoviruses)

- VI: ssRNA-RT viruses (+ strand or sense) RNA with DNA intermediate in life-cycle (e.g. Retroviruses)

- VII: dsDNA-RT viruses DNA with RNA intermediate in life-cycle (e.g. Hepadnaviruses)

Role in human disease

[edit]

Examples of common human diseases caused by viruses include the common cold, influenza, chickenpox, and cold sores. Many serious diseases such as rabies, Ebola virus disease, AIDS (HIV), avian influenza, and SARS are caused by viruses. The relative ability of viruses to cause disease is described in terms of virulence. Other diseases are under investigation to discover if they have a virus as the causative agent, such as the possible connection between human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6) and neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis and chronic fatigue syndrome.[109] There is controversy over whether the bornavirus, previously thought to cause neurological diseases in horses, could be responsible for psychiatric illnesses in humans.[110]

Viruses have different mechanisms by which they produce disease in an organism, which depends largely on the viral species. Mechanisms at the cellular level primarily include cell lysis, the breaking open and subsequent death of the cell. In multicellular organisms, if enough cells die, the whole organism will start to suffer the effects. Although viruses cause disruption of healthy homeostasis, resulting in disease, they may exist relatively harmlessly within an organism. An example would include the ability of the herpes simplex virus, which causes cold sores, to remain in a dormant state within the human body. This is called latency[111] and is a characteristic of the herpes viruses, including Epstein–Barr virus, which causes glandular fever, and varicella zoster virus, which causes chickenpox and shingles. Most people have been infected with at least one of these types of herpes virus.[112] These latent viruses might sometimes be beneficial, as the presence of the virus can increase immunity against bacterial pathogens, such as Yersinia pestis.[113]

Some viruses can cause lifelong or chronic infections, where the viruses continue to replicate in the body despite the host's defence mechanisms.[114] This is common in hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections. People chronically infected are known as carriers, as they serve as reservoirs of infectious virus.[115] In populations with a high proportion of carriers, the disease is said to be endemic.[116]

Epidemiology

[edit]Viral epidemiology is the branch of medical science that deals with the transmission and control of virus infections in humans. Transmission of viruses can be vertical, which means from mother to child, or horizontal, which means from person to person. Examples of vertical transmission include hepatitis B virus and HIV, where the baby is born already infected with the virus.[117] Another, more rare, example is the varicella zoster virus, which, although causing relatively mild infections in children and adults, can be fatal to the foetus and newborn baby.[118]

Horizontal transmission is the most common mechanism of spread of viruses in populations.[119] Horizontal transmission can occur when body fluids are exchanged during sexual activity, by exchange of saliva or when contaminated food or water is ingested. It can also occur when aerosols containing viruses are inhaled or by insect vectors such as when infected mosquitoes penetrate the skin of a host.[119] Most types of viruses are restricted to just one or two of these mechanisms and they are referred to as "respiratory viruses" or "enteric viruses" and so forth. The rate or speed of transmission of viral infections depends on factors that include population density, the number of susceptible individuals, (i.e., those not immune),[120] the quality of healthcare and the weather.[121]

Epidemiology is used to break the chain of infection in populations during outbreaks of viral diseases.[13]: 264 Control measures are used that are based on knowledge of how the virus is transmitted. It is important to find the source, or sources, of the outbreak and to identify the virus. Once the virus has been identified, the chain of transmission can sometimes be broken by vaccines. When vaccines are not available, sanitation and disinfection can be effective. Often, infected people are isolated from the rest of the community, and those that have been exposed to the virus are placed in quarantine.[13]: 894 To control the outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in cattle in Britain in 2001, thousands of cattle were slaughtered.[122] Most viral infections of humans and other animals have incubation periods during which the infection causes no signs or symptoms.[13]: 170 Incubation periods for viral diseases range from a few days to weeks, but are known for most infections.[13]: 170–172 Somewhat overlapping, but mainly following the incubation period, there is a period of communicability—a time when an infected individual or animal is contagious and can infect another person or animal.[13]: 170–172 This, too, is known for many viral infections, and knowledge of the length of both periods is important in the control of outbreaks.[13]: 272 When outbreaks cause an unusually high proportion of cases in a population, community, or region, they are called epidemics. If outbreaks spread worldwide, they are called pandemics.[13]: 891

Epidemics and pandemics

[edit]

A pandemic is a worldwide epidemic. The 1918 flu pandemic, which lasted until 1919, was a category 5 influenza pandemic caused by an unusually severe and deadly influenza A virus. The victims were often healthy young adults, in contrast to most influenza outbreaks, which predominantly affect juvenile, elderly, or otherwise-weakened patients.[26]: 409–415 Older estimates say it killed 40–50 million people,[123] while more recent research suggests that it may have killed as many as 100 million people, or 5% of the world's population in 1918.[124]

Although viral pandemics are rare events, HIV—which evolved from viruses found in monkeys and chimpanzees—has been pandemic since at least the 1980s.[125] During the 20th century there were four pandemics caused by influenza virus and those that occurred in 1918, 1957 and 1968 were severe.[126] Most researchers believe that HIV originated in sub-Saharan Africa during the 20th century;[127] it is now a pandemic, with an estimated 37.9 million people now living with the disease worldwide.[128] There were about 770,000 deaths from AIDS in 2018.[129] The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate that AIDS has killed more than 25 million people since it was first recognised on 5 June 1981, making it one of the most destructive epidemics in recorded history.[130] In 2007 there were 2.7 million new HIV infections and 2 million HIV-related deaths.[131]

Several highly lethal viral pathogens are members of the Filoviridae. Filoviruses are filament-like viruses that cause viral hemorrhagic fever, and include ebolaviruses and marburgviruses. Marburg virus, first discovered in 1967, attracted widespread press attention in April 2005 for an outbreak in Angola.[132] Ebola virus disease has also caused intermittent outbreaks with high mortality rates since 1976 when it was first identified. The worst and most recent one is the 2013–2016 West Africa epidemic.[133]

Except for smallpox, most pandemics are caused by newly evolved viruses. These "emergent" viruses are usually mutants of less harmful viruses that have circulated previously either in humans or other animals.[134]

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) are caused by new types of coronaviruses. Other coronaviruses are known to cause mild infections in humans,[135] so the virulence and rapid spread of SARS infections—that by July 2003 had caused around 8,000 cases and 800 deaths—was unexpected and most countries were not prepared.[136]

A related coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-Cov-2), thought to have originated in bats, emerged in Wuhan, China in November 2019 and spread rapidly around the world. Infections with the virus caused the COVID-19 pandemic that started in 2020.[94][137][138] Unprecedented restrictions in peacetime were placed on international travel,[139] and curfews were imposed in several major cities worldwide in response to the pandemic.[140]

Cancer

[edit]Viruses are an established cause of cancer in humans and other species. Viral cancers occur only in a minority of infected persons (or animals). Cancer viruses come from a range of virus families, including both RNA and DNA viruses, and so there is no single type of "oncovirus" (an obsolete term originally used for acutely transforming retroviruses). The development of cancer is determined by a variety of factors such as host immunity[141] and mutations in the host.[142] Viruses accepted to cause human cancers include some genotypes of human papillomavirus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, Epstein–Barr virus, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and human T-lymphotropic virus. The most recently discovered human cancer virus is a polyomavirus (Merkel cell polyomavirus) that causes most cases of a rare form of skin cancer called Merkel cell carcinoma.[143] Hepatitis viruses can develop into a chronic viral infection that leads to liver cancer.[144][145] Infection by human T-lymphotropic virus can lead to tropical spastic paraparesis and adult T-cell leukaemia.[146] Human papillomaviruses are an established cause of cancers of cervix, skin, anus, and penis.[147] Within the Herpesviridae, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus causes Kaposi's sarcoma and body-cavity lymphoma, and Epstein–Barr virus causes Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, B lymphoproliferative disorder, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.[148] Merkel cell polyomavirus closely related to SV40 and mouse polyomaviruses that have been used as animal models for cancer viruses for over 50 years.[149]

Host defence mechanisms

[edit]The body's first line of defence against viruses is the innate immune system. This comprises cells and other mechanisms that defend the host from infection in a non-specific manner. This means that the cells of the innate system recognise, and respond to, pathogens in a generic way, but, unlike the adaptive immune system, it does not confer long-lasting or protective immunity to the host.[150]

RNA interference is an important innate defence against viruses.[151] Many viruses have a replication strategy that involves double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). When such a virus infects a cell, it releases its RNA molecule or molecules, which immediately bind to a protein complex called a dicer that cuts the RNA into smaller pieces. A biochemical pathway—the RISC complex—is activated, which ensures cell survival by degrading the viral mRNA. Rotaviruses have evolved to avoid this defence mechanism by not uncoating fully inside the cell, and releasing newly produced mRNA through pores in the particle's inner capsid. Their genomic dsRNA remains protected inside the core of the virion.[152][153]

When the adaptive immune system of a vertebrate encounters a virus, it produces specific antibodies that bind to the virus and often render it non-infectious. This is called humoral immunity. Two types of antibodies are important. The first, called IgM, is highly effective at neutralising viruses but is produced by the cells of the immune system only for a few weeks. The second, called IgG, is produced indefinitely. The presence of IgM in the blood of the host is used to test for acute infection, whereas IgG indicates an infection sometime in the past.[154] IgG antibody is measured when tests for immunity are carried out.[155]

Antibodies can continue to be an effective defence mechanism even after viruses have managed to gain entry to the host cell. A protein that is in cells, called TRIM21, can attach to the antibodies on the surface of the virus particle. This primes the subsequent destruction of the virus by the enzymes of the cell's proteosome system.[156]

A second defence of vertebrates against viruses is called cell-mediated immunity and involves immune cells known as T cells. The body's cells constantly display short fragments of their proteins on the cell's surface, and, if a T cell recognises a suspicious viral fragment there, the host cell is destroyed by 'killer T' cells and the virus-specific T-cells proliferate. Cells such as the macrophage are specialists at this antigen presentation.[157] The production of interferon is an important host defence mechanism. This is a hormone produced by the body when viruses are present. Its role in immunity is complex; it eventually stops the viruses from reproducing by killing the infected cell and its close neighbours.[158]

Not all virus infections produce a protective immune response in this way. HIV evades the immune system by constantly changing the amino acid sequence of the proteins on the surface of the virion. This is known as "escape mutation" as the viral epitopes escape recognition by the host immune response. These persistent viruses evade immune control by sequestration, blockade of antigen presentation, cytokine resistance, evasion of natural killer cell activities, escape from apoptosis, and antigenic shift.[159] Other viruses, called 'neurotropic viruses', are disseminated by neural spread where the immune system may be unable to reach them due to immune privilege.[160]

Prevention and treatment

[edit]Because viruses use vital metabolic pathways within host cells to replicate, they are difficult to eliminate without using drugs that cause toxic effects to host cells in general. The most effective medical approaches to viral diseases are vaccinations to provide immunity to infection, and antiviral drugs that selectively interfere with viral replication.

Vaccines

[edit]Vaccination is a cheap and effective way of preventing infections by viruses. Vaccines were used to prevent viral infections long before the discovery of the actual viruses. Their use has resulted in a dramatic decline in morbidity (illness) and mortality (death) associated with viral infections such as polio, measles, mumps and rubella.[161] Smallpox infections have been eradicated.[162] Vaccines are available to prevent over thirteen viral infections of humans,[163] and more are used to prevent viral infections of animals.[164] Vaccines can consist of live-attenuated or killed viruses, viral proteins (antigens), or RNA.[165][166] Live vaccines contain weakened forms of the virus, which do not cause the disease but, nonetheless, confer immunity. Such viruses are called attenuated. Live vaccines can be dangerous when given to people with a weak immunity (who are described as immunocompromised), because in these people, the weakened virus can cause the original disease.[167] Biotechnology and genetic engineering techniques are used to produce subunit vaccines. These vaccines use only the capsid proteins of the virus. Hepatitis B vaccine is an example of this type of vaccine.[168] Subunit vaccines are safe for immunocompromised patients because they cannot cause the disease.[169] The yellow fever virus vaccine, a live-attenuated strain called 17D, is probably the safest and most effective vaccine ever generated.[170]

Antiviral drugs

[edit]

Antiviral drugs are often nucleoside analogues (fake DNA building-blocks), which viruses mistakenly incorporate into their genomes during replication.[171] The life-cycle of the virus is then halted because the newly synthesised DNA is inactive. This is because these analogues lack the hydroxyl groups, which, along with phosphorus atoms, link together to form the strong "backbone" of the DNA molecule. This is called DNA chain termination.[172] Examples of nucleoside analogues are aciclovir for Herpes simplex virus infections and lamivudine for HIV and hepatitis B virus infections. Aciclovir is one of the oldest and most frequently prescribed antiviral drugs.[173] Other antiviral drugs in use target different stages of the viral life cycle. HIV is dependent on a proteolytic enzyme called the HIV-1 protease for it to become fully infectious. There is a large class of drugs called protease inhibitors that inactivate this enzyme.[174] There are around thirteen classes of antiviral drugs each targeting different viruses or stages of viral replication.[171]

Hepatitis C is caused by an RNA virus. In 80% of people infected, the disease is chronic, and without treatment, they are infected for the remainder of their lives. There are effective treatments that use direct-acting antivirals.[175] The treatment of chronic carriers of the hepatitis B virus has also been developed by using similar strategies that include lamivudine and other anti-viral drugs.[176]

Infection in other species

[edit]Viruses infect all cellular life and, although viruses occur universally, each cellular species has its own specific range that often infects only that species.[6]: 3 Some viruses, called satellites, can replicate only within cells that have already been infected by another virus.[30]

Animal viruses

[edit]Viruses are important pathogens of livestock. Diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease and bluetongue are caused by viruses.[177] Companion animals such as cats, dogs, and horses, if not vaccinated, are susceptible to serious viral infections. Canine parvovirus is caused by a small DNA virus and infections are often fatal in pups.[178] Like all invertebrates, the honey bee is susceptible to many viral infections.[179] Most viruses co-exist harmlessly in their host and cause no signs or symptoms of disease.[6]: 4

Plant viruses

[edit]

There are many types of plant viruses, but often they cause only a loss of yield, and it is not economically viable to try to control them. Plant viruses are often spread from plant to plant by organisms, known as vectors. These are usually insects, but some fungi, nematode worms, single-celled organisms, and parasitic plants are vectors.[180] When control of plant virus infections is considered economical, for perennial fruits, for example, efforts are concentrated on killing the vectors and removing alternate hosts such as weeds.[13]: 802 Plant viruses cannot infect humans and other animals because they can reproduce only in living plant cells.[13]: 799–807

Originally from Peru, the potato has become a staple crop worldwide.[181] The potato virus Y causes disease in potatoes and related species including tomatoes and peppers. In the 1980s, this virus acquired economical importance when it proved difficult to control in seed potato crops. Transmitted by aphids, this virus can reduce crop yields by up to 80 per cent, causing significant losses to potato yields.[182]

Plants have elaborate and effective defence mechanisms against viruses. One of the most effective is the presence of so-called resistance (R) genes. Each R gene confers resistance to a particular virus by triggering localised areas of cell death around the infected cell, which can often be seen with the unaided eye as large spots. This stops the infection from spreading.[183] RNA interference is also an effective defence in plants.[13]: 809 When they are infected, plants often produce natural disinfectants that kill viruses, such as salicylic acid, nitric oxide, and reactive oxygen molecules.[184]

Plant virus particles or virus-like particles (VLPs) have applications in both biotechnology and nanotechnology. The capsids of most plant viruses are simple and robust structures and can be produced in large quantities either by the infection of plants or by expression in a variety of heterologous systems. Plant virus particles can be modified genetically and chemically to encapsulate foreign material and can be incorporated into supramolecular structures for use in biotechnology.[185]

Bacterial viruses

[edit]

Bacteriophages are a common and diverse group of viruses and are the most abundant biological entity in aquatic environments—there are up to ten times more of these viruses in the oceans than there are bacteria,[186] reaching levels of 250,000,000 bacteriophages per millilitre of seawater.[187] These viruses infect specific bacteria by binding to surface receptor molecules and then entering the cell. Within a short amount of time, in some cases, just minutes, bacterial polymerase starts translating viral mRNA into protein. These proteins go on to become either new virions within the cell, helper proteins, which help assembly of new virions, or proteins involved in cell lysis. Viral enzymes aid in the breakdown of the cell membrane, and, in the case of the T4 phage, in just over twenty minutes after injection over three hundred phages could be released.[13]: 834–835

The major way bacteria defend themselves from bacteriophages is by producing enzymes that destroy foreign DNA. These enzymes, called restriction endonucleases, cut up the viral DNA that bacteriophages inject into bacterial cells.[188] Bacteria also contain a system that uses CRISPR sequences to retain fragments of the genomes of viruses that the bacteria have come into contact with previously, which allows them to block the virus's replication through a form of RNA interference.[189][190] This genetic system provides bacteria with acquired immunity to infection.[191]

Some bacteriophages are called "temperate" because they cause latent infections and do not immediately destroy their host cells. Instead, their DNA is incorporated with the host cell's as a prophage. These latent infections become productive when the prophage DNA is activated by stimuli such as changes in the environment.[192] The intestines of animals, including humans, contain temperate bacteriophages, which are activated by various stimuli including changes in diet and antibiotics.[193] Although first observed in bacteriophages, many other viruses are known to form proviruses including HIV.[192][194]

Archaeal viruses

[edit]Some viruses replicate within archaea: these are DNA viruses with unusual and sometimes unique shapes.[4][55] These viruses have been studied in most detail in the thermophilic archaea, particularly the orders Sulfolobales and Thermoproteales.[195] Defences against these viruses involve RNA interference from repetitive DNA sequences within archaean genomes that are related to the genes of the viruses.[196][197] Most archaea have CRISPR–Cas systems as an adaptive defence against viruses. These enable archaea to retain sections of viral DNA, which are then used to target and eliminate subsequent infections by the virus using a process similar to RNA interference.[198]

Role in aquatic ecosystems

[edit]Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in aquatic environments.[2] There are about ten million of them in a teaspoon of seawater.[199] Most of these viruses are bacteriophages infecting heterotrophic bacteria and cyanophages infecting cyanobacteria and they are essential to the regulation of saltwater and freshwater ecosystems.[200] Bacteriophages are harmless to plants and animals, and are essential to the regulation of marine and freshwater ecosystems[201] are important mortality agents of phytoplankton, the base of the foodchain in aquatic environments.[202] They infect and destroy bacteria in aquatic microbial communities, and are one of the most important mechanisms of recycling carbon and nutrient cycling in marine environments. The organic molecules released from the dead bacterial cells stimulate fresh bacterial and algal growth, in a process known as the viral shunt.[203] In particular, lysis of bacteria by viruses has been shown to enhance nitrogen cycling and stimulate phytoplankton growth.[204] Viral activity may also affect the biological pump, the process whereby carbon is sequestered in the deep ocean.[205]

Microorganisms constitute more than 90% of the biomass in the sea. It is estimated that viruses kill approximately 20% of this biomass each day and that there are 10 to 15 times as many viruses in the oceans as there are bacteria and archaea.[206] Viruses are also major agents responsible for the destruction of phytoplankton including harmful algal blooms,[207] The number of viruses in the oceans decreases further offshore and deeper into the water, where there are fewer host organisms.[205]

In January 2018, scientists reported that 800 million viruses, mainly of marine origin, are deposited daily from the Earth's atmosphere onto every square meter of the planet's surface, as the result of a global atmospheric stream of viruses, circulating above the weather system but below the altitude of usual airline travel, distributing viruses around the planet.[208][209]

Like any organism, marine mammals are susceptible to viral infections. In 1988 and 2002, thousands of harbour seals were killed in Europe by phocine distemper virus.[210] Many other viruses, including caliciviruses, herpesviruses, adenoviruses and parvoviruses, circulate in marine mammal populations.[205]

In December 2022, scientists reported the first observation of virovory via an experiment on pond water containing chlorovirus, which commonly infects green algae in freshwater environments. When all other microbial food sources were removed from the water, the ciliate Halteria was observed to have increased in number due to the active consumption of chlorovirus as a food source instead of its typical bacterivore diet.[211][212]

Role in evolution

[edit]Viruses are an important natural means of transferring genes between different species, which increases genetic diversity and drives evolution.[9][213][214] It is thought that viruses played a central role in early evolution, before the diversification of the last universal common ancestor into bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes.[215] Viruses are still one of the largest reservoirs of unexplored genetic diversity on Earth.[205]

Applications

[edit]Life sciences and medicine

[edit]

Viruses are important to the study of molecular and cell biology as they provide simple systems that can be used to manipulate and investigate the functions of cells.[26]: 8 The study and use of viruses have provided valuable information about aspects of cell biology.[216] For example, viruses have been useful in the study of genetics and helped our understanding of the basic mechanisms of molecular genetics, such as DNA replication, transcription, RNA processing, translation, protein transport, and immunology.

Geneticists often use viruses as vectors to introduce genes into cells that they are studying. This is useful for making the cell produce a foreign substance, or to study the effect of introducing a new gene into the genome. Similarly, virotherapy uses viruses as vectors to treat various diseases, as they can specifically target cells and DNA. It shows promising use in the treatment of cancer and in gene therapy. Eastern European scientists have used phage therapy as an alternative to antibiotics for some time, and interest in this approach is increasing, because of the high level of antibiotic resistance now found in some pathogenic bacteria.[217] The expression of heterologous proteins by viruses is the basis of several manufacturing processes that are currently being used for the production of various proteins such as vaccine antigens and antibodies. Industrial processes have been recently developed using viral vectors and several pharmaceutical proteins are currently in pre-clinical and clinical trials.[218]

Virotherapy

[edit]Virotherapy involves the use of genetically modified viruses to treat diseases.[219] Viruses have been modified by scientists to reproduce in cancer cells and destroy them but not infect healthy cells. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), for example, is a modified herpes simplex virus that has had a gene, which is required for viruses to replicate in healthy cells, deleted and replaced with a human gene (GM-CSF) that stimulates immunity. When this virus infects cancer cells, it destroys them and in doing so the presence the GM-CSF gene attracts dendritic cells from the surrounding tissues of the body. The dendritic cells process the dead cancer cells and present components of them to other cells of the immune system.[220] Having completed successful clinical trials, the virus gained approval for the treatment of melanoma in late 2015.[221] Viruses that have been reprogrammed to kill cancer cells are called oncolytic viruses.[222]

Materials science and nanotechnology

[edit]From the viewpoint of a materials scientist, viruses can be regarded as organic nanoparticles.[223] Their surface carries specific tools that enable them to cross the barriers of their host cells. The size and shape of viruses and the number and nature of the functional groups on their surface are precisely defined. As such, viruses are commonly used in materials science as scaffolds for covalently linked surface modifications. A particular quality of viruses is that they can be tailored by directed evolution. The powerful techniques developed by life sciences are becoming the basis of engineering approaches towards nanomaterials, opening a wide range of applications far beyond biology and medicine.[224] Because of their size, shape, and well-defined chemical structures, viruses have been used as templates for organising materials on the nanoscale. Examples include the work at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., using Cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV) particles to amplify signals in DNA microarray based sensors. In this application, the virus particles separate the fluorescent dyes used for signalling to prevent the formation of non-fluorescent dimers that act as quenchers.[225] Another example is the use of CPMV as a nanoscale breadboard for molecular electronics.[226]

Synthetic viruses

[edit]Many viruses can be synthesised de novo ("from scratch"). The first synthetic virus was created in 2002.[227] Although somewhat of a misconception, it is not the actual virus that is synthesised, but rather its DNA genome (in case of a DNA virus), or a cDNA copy of its genome (in case of RNA viruses). For many virus families the naked synthetic DNA or RNA (once enzymatically converted back from the synthetic cDNA) is infectious when introduced into a cell. That is, they contain all the necessary information to produce new viruses. This technology is now being used to investigate novel vaccine strategies.[228] The ability to synthesise viruses has far-reaching consequences, since viruses can no longer be regarded as extinct, as long as the information of their genome sequence is known and permissive cells are available. As of June 2021, the full-length genome sequences of 11,464 different viruses, including smallpox, are publicly available in an online database maintained by the National Institutes of Health.[229]

Weapons

[edit]The ability of viruses to cause devastating epidemics in human societies has led to the concern that viruses could be weaponised for biological warfare. Further concern was raised by the successful recreation of the infamous 1918 influenza virus in a laboratory.[230] The smallpox virus devastated numerous societies throughout history before its eradication. There are only two centres in the world authorised by the WHO to keep stocks of smallpox virus: the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR in Russia and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States.[231] It may be used as a weapon,[231] as the vaccine for smallpox sometimes had severe side-effects, it is no longer used routinely in any country. Thus, much of the modern human population has almost no established resistance to smallpox and would be vulnerable to the virus.[231]

See also

[edit]- Cross-species transmission

- Glossary of virology

- Law of declining virulence – Disproved hypothesis of epidemiologist Theobald Smith

- Non-cellular life

- Gene transfer agent

- Retrozyme

- Smallest organisms

- Theory of virulence – Theory by biologist Paul W. Ewald

- Viral metagenomics

- Viroplasm

- Zoonosis

References

[edit]- ^ Wu KJ (15 April 2020). "There are more viruses than stars in the universe. Why do only some infect us? – More than a quadrillion quadrillion individual viruses exist on Earth, but most are not poised to hop into humans. Can we find the ones that are?". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Koonin EV, Senkevich TG, Dolja VV (September 2006). "The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells". Biology Direct. 1 (1): 29. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-1-29. PMC 1594570. PMID 16984643.

- ^ Zimmer C (26 February 2021). "The Secret Life of a Coronavirus - An oily, 100-nanometer-wide bubble of genes has killed more than two million people and reshaped the world. Scientists don't quite know what to make of it". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ a b Lawrence CM, Menon S, Eilers BJ, Bothner B, Khayat R, Douglas T, et al. (May 2009). "Structural and functional studies of archaeal viruses". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (19): 12599–603. doi:10.1074/jbc.R800078200. PMC 2675988. PMID 19158076.

- ^ Edwards RA, Rohwer F (June 2005). "Viral metagenomics". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 3 (6): 504–10. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1163. PMID 15886693. S2CID 8059643.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Dimmock NJ, Easton AJ, Leppard K (2007). Introduction to Modern Virology (6th ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-3645-7.

- ^ a b c "Virus Taxonomy: 2024 Release". talk.ictvonline.org. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Retrieved 10 March 2025.

- ^ a b Breitbart M, Rohwer F (June 2005). "Here a virus, there a virus, everywhere the same virus?". Trends in Microbiology. 13 (6): 278–84. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2005.04.003. PMID 15936660.

- ^ a b Canchaya C, Fournous G, Chibani-Chennoufi S, Dillmann ML, Brüssow H (August 2003). "Phage as agents of lateral gene transfer". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 6 (4): 417–24. doi:10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00086-9. PMID 12941415.

- ^ a b Rybicki EP (1990). "The classification of organisms at the edge of life, or problems with virus systematics". South African Journal of Science. 86: 182–86.

- ^ a b Koonin EV, Starokadomskyy P (October 2016). "Are viruses alive? The replicator paradigm sheds decisive light on an old but misguided question". Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 59: 125–34. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2016.02.016. PMC 5406846. PMID 26965225.

- ^ Robilotti E, Deresinski S, Pinsky BA (January 2015). "Norovirus". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 28 (1): 134–64. doi:10.1128/CMR.00075-14. PMC 4284304. PMID 25567225.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Shors T (2017). Understanding Viruses. Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1-284-02592-7.

- ^ "Virus, n.". OED Online. Oxford University Press. March 2015.

- ^ a b Harper D (2011). "virus". The Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ "Virulent, adj.". OED Online. Oxford University Press. March 2015.

- ^ Harper D (2011). "virulent". The Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ Buschard K, Thon R (2003). "Diabetic Animal Models". In Hau J, Van Hoosier Jr GL (eds.). Handbook of Laboratory Animal Science. Animal Models. Vol. II (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 163, 166.

- ^ William T. Stearn: Botanical Latin. History, Grammar, Syntax, Terminology and Vocabulary. David & Charles, 3rd ed., 1983. Quote: "Virus: virus (s.n. II), gen. sing. viri, nom. pl. vira, gen. pl. vīrorum (to be distinguished from virorum, of men)."

- ^ Harper D (2011). "viral". The Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ Harper D (2011). "virion". The Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ Casjens S (2010). Mahy BW, Van Regenmortel MH (eds.). Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology. Boston: Academic Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-12-375146-1.

- ^ Iyer LM, Balaji S, Koonin EV, Aravind L (April 2006). "Evolutionary genomics of nucleo-cytoplasmic large DNA viruses". Virus Research. 117 (1): 156–84. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.009. PMID 16494962.

- ^ a b Sanjuán R, Nebot MR, Chirico N, Mansky LM, Belshaw R (October 2010). "Viral mutation rates". Journal of Virology. 84 (19): 9733–9748. doi:10.1128/JVI.00694-10. PMC 2937809. PMID 20660197.

- ^ Krupovic M, Dolja VV, Koonin EV (July 2019). "Origin of viruses: primordial replicators recruiting capsids from hosts" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 17 (7): 449–58. doi:10.1038/s41579-019-0205-6. PMID 31142823. S2CID 256744818.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Collier L, Balows A, Sussman M (1998). Mahy B, Collier LA (eds.). Topley and Wilson's Microbiology and Microbial Infections. Virology. Vol. 1 (9th ed.). ISBN 0-340-66316-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mahy WJ, Regenmortel MH, eds. (2009). Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology. Oxford: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-375146-1.

- ^ McClintock B (June 1950). "The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 36 (6): 344–55. Bibcode:1950PNAS...36..344M. doi:10.1073/pnas.36.6.344. PMC 1063197. PMID 15430309.

- ^ Tsagris EM, Martínez de Alba AE, Gozmanova M, Kalantidis K (November 2008). "Viroids". Cellular Microbiology. 10 (11): 2168–79. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01231.x. PMID 18764915. S2CID 221581424.

- ^ a b La Scola B, Desnues C, Pagnier I, Robert C, Barrassi L, Fournous G, et al. (September 2008). "The virophage as a unique parasite of the giant mimivirus". Nature. 455 (7209): 100–04. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..100L. doi:10.1038/nature07218. PMID 18690211. S2CID 4422249.

- ^ Dimmock pp. 15–16

- ^ Zerbini FM, Kitajima EW (September 2022). "From Contagium vivum fluidum to Riboviria: A Tobacco Mosaic Virus-Centric History of Virus Taxonomy". Biomolecules. 12 (10): 1363. doi:10.3390/biom12101363. PMC 9599303. PMID 36291572.

- ^ Holmes EC (October 2007). "Viral evolution in the genomic age". PLOS Biology. 5 (10): e278. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050278. PMC 1994994. PMID 17914905.

- ^ Wimmer E, Mueller S, Tumpey TM, Taubenberger JK (December 2009). "Synthetic viruses: a new opportunity to understand and prevent viral disease". Nature Biotechnology. 27 (12): 1163–72. doi:10.1038/nbt.1593. PMC 2819212. PMID 20010599.

- ^ Horn M (2008). "Chlamydiae as symbionts in eukaryotes". Annual Review of Microbiology. 62: 113–31. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162818. PMID 18473699.

- ^ Diop A, Raoult D, Fournier PE (February 2019). "Paradoxical evolution of rickettsial genomes". Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 10 (2): 462–469. doi:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.11.007. PMID 30448253.

- ^ Forterre, P. The virocell concept and environmental microbiology. ISME J 7, 233–236 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.110

- ^ DeLong JP, Al-Sammak MA, Al-Ameeli ZT, Dunigan DD, Edwards KF, Fuhrmann JJ, et al. (February 2022). "Towards an integrative view of virus phenotypes". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 20 (2): 83–94. doi:10.1038/s41579-021-00612-w. PMID 34522049.

- ^ Krasner R (2014). The microbial challenge: a public health perspective. Burlington, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1-4496-7375-8. OCLC 794228026.

- ^ Kiselev NA, Sherman MB, Tsuprun VL (1990). "Negative staining of proteins". Electron Microscopy Reviews. 3 (1): 43–72. doi:10.1016/0892-0354(90)90013-I. PMID 1715774.

- ^ Caspar DL, Klug A (1962). "Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses". Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 27: 1–24. doi:10.1101/sqb.1962.027.001.005. PMID 14019094.

- ^ Crick FH, Watson JD (March 1956). "Structure of small viruses". Nature. 177 (4506): 473–75. Bibcode:1956Natur.177..473C. doi:10.1038/177473a0. PMID 13309339. S2CID 5740221.

- ^ Falvo MR, Washburn S, Superfine R, Finch M, Brooks FP, Chi V, et al. (March 1997). "Manipulation of individual viruses: friction and mechanical properties". Biophysical Journal. 72 (3): 1396–403. Bibcode:1997BpJ....72.1396F. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78786-1. PMC 1184522. PMID 9138585.

- ^ Kuznetsov YG, Malkin AJ, Lucas RW, Plomp M, McPherson A (September 2001). "Imaging of viruses by atomic force microscopy". The Journal of General Virology. 82 (Pt 9): 2025–34. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-82-9-2025. PMID 11514711.

- ^ Straus SK, Bo HE (2018). "Filamentous Bacteriophage Proteins and Assembly". Virus Protein and Nucleoprotein Complexes. Subcellular Biochemistry. Vol. 88. pp. 261–79. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8456-0_12. ISBN 978-981-10-8455-3. PMID 29900501.

- ^ Wilson DP (2016). "Protruding Features of Viral Capsids Are Clustered on Icosahedral Great Circles". PLOS ONE. 11 (4) e0152319. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1152319W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152319. PMC 4821576. PMID 27045511.

- ^ Casens S (2009). Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 167–74. ISBN 978-0-12-375146-1.

- ^ Dhama K, Khan S, Tiwari R, Sircar S, Bhat S, Malik YS, et al. (September 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019-COVID-19". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 33 (4). doi:10.1128/CMR.00028-20. PMC 7405836. PMID 32580969.

- ^ Rossmann MG, Mesyanzhinov VV, Arisaka F, Leiman PG (April 2004). "The bacteriophage T4 DNA injection machine". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 14 (2): 171–80. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2004.02.001. PMID 15093831.