Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

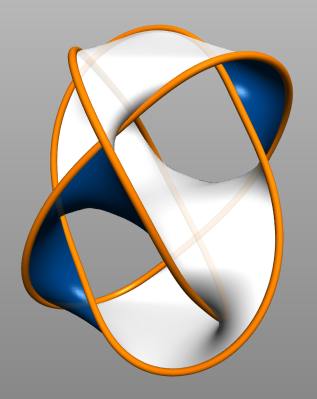

Seifert surface

View on Wikipedia

In mathematics, a Seifert surface (named after German mathematician Herbert Seifert[1][2]) is an orientable surface whose boundary is a given knot or link.

Such surfaces can be used to study the properties of the associated knot or link. For example, many knot invariants are most easily calculated using a Seifert surface. Seifert surfaces are also interesting in their own right, and the subject of considerable research.

Specifically, let L be a tame oriented knot or link in Euclidean 3-space (or in the 3-sphere). A Seifert surface is a compact, connected, oriented surface S embedded in 3-space whose boundary is L such that the orientation on L is just the induced orientation from S.

Note that any compact, connected, oriented surface with nonempty boundary in Euclidean 3-space is the Seifert surface associated to its boundary link. A single knot or link can have many different inequivalent Seifert surfaces. A Seifert surface must be oriented. It is possible to associate surfaces to knots which are not oriented nor orientable, as well.

Examples

[edit]

The standard Möbius strip has the unknot for a boundary but is not a Seifert surface for the unknot because it is not orientable.

The "checkerboard" coloring of the usual minimal crossing projection of the trefoil knot gives a Mobius strip with three half twists. As with the previous example, this is not a Seifert surface as it is not orientable. Applying Seifert's algorithm to this diagram, as expected, does produce a Seifert surface; in this case, it is a punctured torus of genus g = 1, and the Seifert matrix is

Existence and Seifert matrix

[edit]It is a theorem that any link always has an associated Seifert surface. This theorem was first published by Frankl and Pontryagin in 1930.[3] A different proof was published in 1934 by Herbert Seifert and relies on what is now called the Seifert algorithm. The algorithm produces a Seifert surface , given a projection of the knot or link in question.

Suppose that link has m components (m = 1 for a knot), the diagram has d crossing points, and resolving the crossings (preserving the orientation of the knot) yields f circles. Then the surface is constructed from f disjoint disks by attaching d bands. The homology group is free abelian on 2g generators, where

is the genus of . The intersection form Q on is skew-symmetric, and there is a basis of 2g cycles with equal to a direct sum of the g copies of the matrix

The 2g × 2g integer Seifert matrix

has the linking number in Euclidean 3-space (or in the 3-sphere) of ai and the "pushoff" of aj in the positive direction of . More precisely, recalling that Seifert surfaces are bicollared, meaning that we can extend the embedding of to an embedding of , given some representative loop which is homology generator in the interior of , the positive pushout is and the negative pushout is .[4]

With this, we have

where V∗ = (v(j, i)) the transpose matrix. Every integer 2g × 2g matrix with arises as the Seifert matrix of a knot with genus g Seifert surface.

The Alexander polynomial is computed from the Seifert matrix by which is a polynomial of degree at most 2g in the indeterminate The Alexander polynomial is independent of the choice of Seifert surface and is an invariant of the knot or link.

The signature of a knot is the signature of the symmetric Seifert matrix It is again an invariant of the knot or link.

Genus of a knot

[edit]Seifert surfaces are not at all unique: a Seifert surface S of genus g and Seifert matrix V can be modified by a topological surgery, resulting in a Seifert surface S′ of genus g + 1 and Seifert matrix

The genus of a knot K is the knot invariant defined by the minimal genus g of a Seifert surface for K.

For instance:

- An unknot—which is, by definition, the boundary of a disc—has genus zero. Moreover, the unknot is the only knot with genus zero.

- The trefoil knot has genus 1, as does the figure-eight knot.

- The genus of a (p, q)-torus knot is (p − 1)(q − 1)/2

- The degree of a knot's Alexander polynomial is a lower bound on twice its genus.

A fundamental property of the genus is that it is additive with respect to the knot sum:

In general, the genus of a knot is difficult to compute, and the Seifert algorithm usually does not produce a Seifert surface of least genus. For this reason other related invariants are sometimes useful. The canonical genus of a knot is the least genus of all Seifert surfaces that can be constructed by the Seifert algorithm, and the free genus is the least genus of all Seifert surfaces whose complement in is a handlebody. (The complement of a Seifert surface generated by the Seifert algorithm is always a handlebody.) For any knot the inequality obviously holds, so in particular these invariants place upper bounds on the genus.[5]

The knot genus is NP-complete by work of Ian Agol, Joel Hass and William Thurston.[6]

It has been shown that there are Seifert surfaces of the same genus that do not become isotopic either topologically or smoothly in the 4-ball.[7][8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Seifert, H. (1934). "Über das Geschlecht von Knoten". Math. Annalen (in German). 110 (1): 571–592. doi:10.1007/BF01448044. S2CID 122221512.

- ^ van Wijk, Jarke J.; Cohen, Arjeh M. (2006). "Visualization of Seifert Surfaces". IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 12 (4): 485–496. Bibcode:2006ITVCG..12..485V. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2006.83. PMID 16805258. S2CID 4131932.

- ^ Frankl, F.; Pontrjagin, L. (1930). "Ein Knotensatz mit Anwendung auf die Dimensionstheorie". Math. Annalen (in German). 102 (1): 785–789. doi:10.1007/BF01782377. S2CID 123184354.

- ^ Dale Rolfsen. Knots and Links. (1976), 146-147.

- ^ Brittenham, Mark (24 September 1998). "Bounding canonical genus bounds volume". arXiv:math/9809142.

- ^ Agol, Ian; Hass, Joel; Thurston, William (2002-05-19). "3-manifold knot genus is NP-complete". Proceedings of the thiry-fourth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing. STOC '02. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 761–766. arXiv:math/0205057. doi:10.1145/509907.510016. ISBN 978-1-58113-495-7. S2CID 10401375 – via author-link.

- ^ Hayden, Kyle; Kim, Seungwon; Miller, Maggie; Park, JungHwan; Sundberg, Isaac (2022-05-30). "Seifert surfaces in the 4-ball". arXiv:2205.15283 [math.GT].

- ^ "Special Surfaces Remain Distinct in Four Dimensions". Quanta Magazine. 2022-06-16. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

External links

[edit]- The SeifertView programme of Jack van Wijk visualizes the Seifert surfaces of knots constructed using Seifert's algorithm.

![{\displaystyle S\times [-1,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e47ae91617b44e3a2f91d571aa9a3e4cffd4137a)