Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Variogram

View on WikipediaIn spatial statistics the theoretical variogram, denoted , is a function describing the degree of spatial dependence of a spatial random field or stochastic process . The semivariogram is half the variogram.

For example, in gold mining, a variogram will give a measure of how much two samples taken from the mining area will vary in gold percentage depending on the distance between those samples. Samples taken far apart will vary more than samples taken close to each other.

Definition

[edit]

The semivariogram was first defined by Matheron (1963) as half the average squared difference between a function and a translated copy of the function separated at distance .[1][2] Formally

where is a point in the geometric field , and is the value at that point. The triple integral is over 3 dimensions. is the separation distance (e.g., in meters or km) of interest. For example, the value could represent the iron content in soil, at some location (with geographic coordinates of latitude, longitude, and elevation) over some region with element of volume . To obtain the semivariogram for a given , all pairs of points at that exact distance would be sampled. In practice it is impossible to sample everywhere, so the empirical variogram is used instead.

The variogram is twice the semivariogram and can be defined, differently, as the variance of the difference between field values at two locations ( and , note change of notation from to and to ) across realizations of the field (Cressie 1993):

If the spatial random field has constant mean , this is equivalent to the expectation for the squared increment of the values between locations and (Wackernagel 2003) (where and are points in space and possibly time):

In the case of a stationary process, the variogram and semivariogram can be represented as a function of the difference between locations only, by the following relation (Cressie 1993):

If the process is furthermore isotropic, then the variogram and semivariogram can be represented by a function of the distance only (Cressie 1993):

The indexes or are typically not written. The terms are used for all three forms of the function. Moreover, the term "variogram" is sometimes used to denote the semivariogram, and the symbol is sometimes used for the variogram, which brings some confusion.[3]

Properties

[edit]According to (Cressie 1993, Chiles and Delfiner 1999, Wackernagel 2003) the theoretical variogram has the following properties:

- The semivariogram is nonnegative , since it is the expectation of a square.

- The semivariogram at distance 0 is always 0, since .

- A function is a semivariogram if and only if it is a conditionally negative definite function, i.e. for all weights subject to and locations it holds:

- which corresponds to the fact that the variance of is given by the negative of this double sum and must be nonnegative.[disputed – discuss]

- If the covariance function C of a stationary process exists, it is related to variogram by

- If the variance V and correlation function c of a stationary process exist, they are related to semivariogram by

- Conversely, the covariance function C of a stationary process can be obtained from the semivariogram and variance as

- If a stationary random field has no spatial dependence (i.e. if ), the semivariogram is the constant everywhere except at the origin, where it is zero.

- The semivariogram is a symmetric function, .

- Consequently, the isotropic semivariogram is an even function .

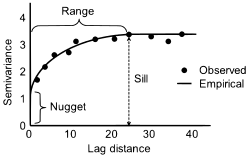

- If the random field is stationary and ergodic, the corresponds to the variance of the field. The limit of the semivariogram with increasing distance is also called its sill.

- As a consequence the semivariogram might be non continuous only at the origin. The height of the jump at the origin is sometimes referred to as nugget or nugget effect.

Parameters

[edit]In summary, the following parameters are often used to describe variograms:

- nugget : The height of the jump of the semivariogram at the discontinuity at the origin.

- sill : Limit of the variogram tending to infinity lag distances.

- range : The distance in which the difference of the variogram from the sill becomes negligible. In models with a fixed sill, it is the distance at which this is first reached; for models with an asymptotic sill, it is conventionally taken to be the distance when the semivariance first reaches 95% of the sill.

Empirical variogram

[edit]Generally, an empirical variogram is needed for measured data, because sample information is not available for every location. The sample information for example could be concentration of iron in soil samples, or pixel intensity on a camera. Each piece of sample information has coordinates for a 2D sample space where and are geographical coordinates. In the case of the iron in soil, the sample space could be 3 dimensional. If there is temporal variability as well (e.g., phosphorus content in a lake) then could be a 4 dimensional vector . For the case where dimensions have different units (e.g., distance and time) then a scaling factor can be applied to each to obtain a modified Euclidean distance.[4]

Sample observations are denoted . Observations may be taken at total different locations (the sample size). This would provide as set of observations at locations . Generally, plots show the semivariogram values as a function of separation distance for multiple steps . In the case of empirical semivariogram, separation distance interval is used rather than exact distances, and usually isotropic conditions are assumed (i.e., that is only a function of and does not depend on other variables such as center position). Then, the empirical semivariogram can be calculated for each bin:

Or in other words, each pair of points separated by (plus or minus some bin width tolerance range ) are found. These form the set of points

The number of these points in this bin is (the set size). Then for each pair of points , the square of the difference in the observation (e.g., soil sample content or pixel intensity) is found (). These squared differences are added together and normalized by the natural number . By definition the result is divided by 2 for the semivariogram at this separation.

For computational speed, only the unique pairs of points are needed. For example, for 2 observations pairs [] taken from locations with separation only [] need to be considered, as the pairs [] do not provide any additional information.

Variogram models

[edit]The empirical variogram cannot be computed at every lag distance and due to variation in the estimation it is not ensured that it is a valid variogram, as defined above. However some geostatistical methods such as kriging need valid semivariograms. In applied geostatistics the empirical variograms are thus often approximated by model function ensuring validity (Chiles&Delfiner 1999). Some important models are (Chiles&Delfiner 1999, Cressie 1993):

- The exponential variogram model

- The spherical variogram model

- The Gaussian variogram model

The parameter has different values in different references, due to the ambiguity in the definition of the range. E.g. is the value used in (Chiles&Delfiner 1999). The indicator function is 1 if and 0 otherwise.

Discussion

[edit]Three functions are used in geostatistics for describing the spatial or the temporal correlation of observations: these are the correlogram, the covariance, and the semivariogram. The last is also more simply called variogram.

The variogram is the key function in geostatistics as it will be used to fit a model of the temporal/spatial correlation of the observed phenomenon. One is thus making a distinction between the experimental variogram that is a visualization of a possible spatial/temporal correlation and the variogram model that is further used to define the weights of the kriging function. Note that the experimental variogram is an empirical estimate of the covariance of a Gaussian process. As such, it may not be positive definite and hence not directly usable in kriging, without constraints or further processing. This explains why only a limited number of variogram models are used: most commonly, the linear, the spherical, the Gaussian, and the exponential models.

Applications

[edit]The empirical variogram is used in geostatistics as a first estimate of the variogram model needed for spatial interpolation by kriging.

- Empirical variograms for the spatiotemporal variability of column-averaged carbon dioxide was used to determine coincidence criteria for satellite and ground-based measurements.[4]

- Empirical variograms were calculated for the density of a heterogeneous material (Gilsocarbon).[5]

- Empirical variograms are calculated from observations of strong ground motion from earthquakes.[6] These models are used for seismic risk and loss assessments of spatially-distributed infrastructure.[7]

Related concepts

[edit]The squared term in the variogram, for instance , can be replaced with different powers: A madogram is defined with the absolute difference, , and a rodogram is defined with the square root of the absolute difference, . Estimators based on these lower powers are said to be more resistant to outliers. They can be generalized as a "variogram of order α",

- ,

in which a variogram is of order 2, a madogram is a variogram of order 1, and a rodogram is a variogram of order 0.5.[8]

When a variogram is used to describe the correlation of different variables it is called cross-variogram. Cross-variograms are used in co-kriging. Should the variable be binary or represent classes of values, one is then talking about indicator variograms. Indicator variograms are used in indicator kriging.

References

[edit]- ^ Matheron, Georges (1963). "Principles of geostatistics". Economic Geology. 58 (8): 1246–1266. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.58.8.1246. ISSN 1554-0774.

- ^ Ford, David. "The Empirical Variogram" (PDF). faculty.washington.edu/edford. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ Bachmaier, Martin; Backes, Matthias (2008-02-24). "Variogram or semivariogram? Understanding the variances in a variogram". Precision Agriculture. 9 (3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 173–175. doi:10.1007/s11119-008-9056-2. ISSN 1385-2256.

- ^ a b Nguyen, H.; Osterman, G.; Wunch, D.; O'Dell, C.; Mandrake, L.; Wennberg, P.; Fisher, B.; Castano, R. (2014). "A method for colocating satellite XCO2 data to ground-based data and its application to ACOS-GOSAT and TCCON". Atmospheric Measurement Techniques. 7 (8): 2631–2644. Bibcode:2014AMT.....7.2631N. doi:10.5194/amt-7-2631-2014. ISSN 1867-8548.

- ^ Arregui Mena, J.D.; et al. (2018). "Characterisation of the spatial variability of material properties of Gilsocarbon and NBG-18 using random fields". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 511: 91–108. Bibcode:2018JNuM..511...91A. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2018.09.008.

- ^ Schiappapietra, Erika; Douglas, John (April 2020). "Modelling the spatial correlation of earthquake ground motion: Insights from the literature, data from the 2016–2017 Central Italy earthquake sequence and ground-motion simulations". Earth-Science Reviews. 203 103139. Bibcode:2020ESRv..20303139S. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103139.

- ^ Sokolov, Vladimir; Wenzel, Friedemann (2011-07-25). "Influence of spatial correlation of strong ground motion on uncertainty in earthquake loss estimation". Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics. 40 (9): 993–1009. doi:10.1002/eqe.1074.

- ^ Olea, Ricardo A. (1991). Geostatistical Glossary and Multilingual Dictionary. Oxford University Press. pp. 47, 67, 81. ISBN 978-0-19-506689-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Cressie, N., 1993, Statistics for spatial data, Wiley Interscience.

- Chiles, J. P., P. Delfiner, 1999, Geostatistics, Modelling Spatial Uncertainty, Wiley-Interscience.

- Wackernagel, H., 2003, Multivariate Geostatistics, Springer.

- Burrough, P. A. and McDonnell, R. A., 1998, Principles of Geographical Information Systems.

- Isobel Clark, 1979, Practical Geostatistics, Applied Science Publishers.

- Clark, I., 1979, Practical Geostatistics, Applied Science Publishers.

- David, M., 1978, Geostatistical Ore Reserve Estimation, Elsevier Publishing.

- Hald, A., 1952, Statistical Theory with Engineering Applications, John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Journel, A. G. and Huijbregts, Ch. J., 1978 Mining Geostatistics, Academic Press.

- Glass, H.J., 2003, Method for assessing quality of the variogram, The Journal of The South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy.

External links

[edit]- AI-GEOSTATS: an educational resource about geostatistics and spatial statistics

- Geostatistics: Lecture by Rudolf Dutter at the Technical University of Vienna Archived 2007-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

![{\displaystyle \gamma (h)={\frac {1}{2}}\iiint _{V}\left[f(M+h)-f(M)\right]^{2}dM,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a814e5cf91fb641086a3cc68817a8adfb0f90003)

![{\displaystyle 2\gamma (\mathbf {s} _{1},\mathbf {s} _{2})={\text{var}}\left(Z(\mathbf {s} _{1})-Z(\mathbf {s} _{2})\right)=E\left[((Z(\mathbf {s} _{1})-Z(\mathbf {s} _{2}))-E[Z(\mathbf {s} _{1})-Z(\mathbf {s} _{2})])^{2}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d2a3b498bf4ad1208a43530bd12e08359066f22)

![{\displaystyle 2\gamma (\mathbf {s} _{1},\mathbf {s} _{2})=E\left[\left(Z(\mathbf {s} _{1})-Z(\mathbf {s} _{2})\right)^{2}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a55f08c148ec3960f3252379ca4bca01457418fd)

![{\displaystyle \gamma (\mathbf {s} _{1},\mathbf {s} _{2})=E\left[|Z(\mathbf {s} _{1})-Z(\mathbf {s} _{2})|^{2}\right]=\gamma (\mathbf {s} _{2},\mathbf {s} _{1})}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/542666ae89aff90a0b63b9ab059d9e5eea061a1c)

![{\displaystyle 2\gamma (\mathbf {s} _{1},\mathbf {s} _{2})=E\left[\left|Z(\mathbf {s} _{1})-Z(\mathbf {s} _{2})\right|^{\alpha }\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ae6875535aca152a2d0b84424c7bb0349166a123)