Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Isogamy

View on Wikipedia

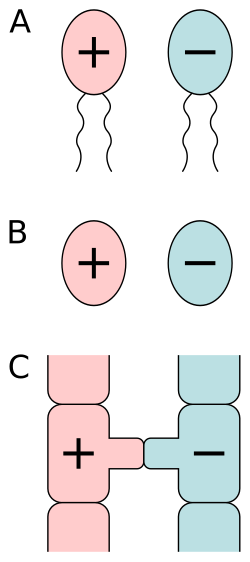

Isogamy is a form of sexual reproduction that involves gametes of the same morphology (indistinguishable in shape and size), and is found in most unicellular eukaryotes.[1] Because both gametes look alike, they generally cannot be classified as male or female.[2] Instead, organisms that reproduce through isogamy are said to have different mating types, most commonly noted as "+" and "−" strains.[3]

Etymology

[edit]The etymology of isogamy derives from the Greek adjective isos (meaning equal) and the Greek verb gameo (meaning to have sex/to reproduce), eventually meaning "equal reproduction" which refers to a hypothetical initial model of equal contribution of resources by both gametes to a zygote in contrast to a later evolutional stage of anisogamy.[4] The term isogamy was first used in the year 1891.[5][6]

Characteristics of isogamous species

[edit]Isogamous species often have two mating types (heterothallism), but sometimes can occur between two haploid individuals that are mitotic descendents (homothallism).[1][Note 1] Some isogamous species have more than two mating types, but the number is usually lower than ten. In some extremely rare cases, such as in some basidiomycete species, a species can have thousands of mating types.[7]

Under the strict definition of isogamy, fertilization occurs when two gametes fuse to form a zygote.[8] Sexual reproduction between two cells that does not involve gametes (e.g. conjugation between two mycelia in basidiomycete fungi), is often called isogamy, although it is not technically isogametic reproduction in the strict sense.[1]

Evolution

[edit]As the first stage in the evolution of sexual reproduction in all known lifeforms, isogamy is thought to have evolved just once, in a single unicellular eukaryote species, the common ancestor of all eukaryotes. It is generally accepted that isogamy is an ancestral state for anisogamy.[1][9] Isogamous reproduction evolved independently in several lineages of plants and animals into anisogamy (species with gametes of male and female types) and subsequently into oogamy (species in which the female gamete is much larger than the male and has no ability to move). This pattern may have been driven by the physical constraints on the mechanisms by which two gametes get together as required for sexual reproduction.[10]

Since it appeared, isogamy has remained the norm in unicellular eukaryote species, and it is possible that isogamy is also evolutionarily stable in multicellular species.[1]

Occurrence

[edit]Almost all unicellular eukaryotes are isogamous.[11] Among multicellular organisms, isogamy is restricted to fungi and eukaryotic algae.[12] Many species of green algae are isogamous. It is typical in the genera Ulva, Hydrodictyon, Tetraspora, Zygnema, Spirogyra, Ulothrix, and Chlamydomonas.[1][13] Many fungi are also isogamous, including single-celled species such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe.[1][14]

In some multicellular fungi, such as basidiomycetes, sexual reproduction takes place between two mycelia, but there is no exchange of gametes.[1]

There are no known examples of isogamous metazoans, red algae or land plants.[1]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Not to be confused with self-incompatibility in plants.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lehtonen, Jussi; Kokko, Hanna; Parker, Geoff A. (2016-10-19). "What do isogamous organisms teach us about sex and the two sexes?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371 (1706). doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0532. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 5031617. PMID 27619696.

- ^ Sawada, Hitoshi; Inoue, Naokazu; Iwano, Megumi (2014). Sexual Reproduction in Animals and Plants. Springer. p. 216. ISBN 978-4-431-54589-7. Archived from the original on 2024-04-04. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ Kumar R, Meena M, Swapnil P (2019). "Anisogamy". In Vonk J, Shackelford T (eds.). Anisogamy. Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_340-1. ISBN 978-3-319-47829-6.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Biology. Vol. 2. Academic Press. 2016-04-14. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-12-800426-5. Archived from the original on 2023-10-06. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- ^ Hartog, M. (17 September 1891). "Isogamy, the union of gametes undistinguishable in size, form, and behaviour". Nature: 484.

- ^ "Definition of ISOGAMOUS". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 2021-09-14. Retrieved 2021-09-14.

- ^ Casselton, L. A. (2002-02-01). "Mate recognition in fungi". Heredity. 88 (2): 142–147. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800035. ISSN 1365-2540.

- ^ Krumbeck, Yvonne; Constable, George W. A.; Rogers, Tim (2020-02-26). "Fitness differences suppress the number of mating types in evolving isogamous species". Royal Society Open Science. 7 (2) 192126. arXiv:1906.07117. Bibcode:2020RSOS....792126K. doi:10.1098/rsos.192126. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 7062084. PMID 32257356.

- ^ Pitnick, Scott S.; Hosken, Dave J.; Birkhead, Tim R. (2008-11-21). Sperm Biology: An Evolutionary Perspective. Academic Press. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-0-08-091987-4. Archived from the original on 2023-10-06. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ Dusenbery, David B. (2009). Living at Micro Scale, Chapter 20. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts ISBN 978-0-674-03116-6.

- ^ Bell, Graham (2008). Selection: The Mechanism of Evolution. OUP Oxford. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-19-856972-5. Archived from the original on 2023-10-06. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ Togashi, Tatsuya; Cox, Paul Alan (2011-04-14). The Evolution of Anisogamy: A Fundamental Phenomenon Underlying Sexual Selection. Cambridge University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-139-50082-1. Archived from the original on 2023-10-06. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ Sharma, O. P. (1986-01-01). Textbook of Algae. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-07-451928-8. Archived from the original on 2023-10-06. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ Heitman, Joseph; Howlett, Barbara J.; Crous, Pedro W.; Stukenbrock, Eva H.; James, Timothy Yong; Gow, Neil A. R. (2020-07-10). The Fungal Kingdom. John Wiley & Sons. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-55581-958-3. Archived from the original on 2023-10-06. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- Sa Geng; Peter De Hoff; James G. Umen (July 8, 2014). "Evolution of Sexes from an Ancestral Mating-Type Specification Parthway". PLOS Biology. 12 (7) e1001904. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001904. PMC 4086717. PMID 25003332.