Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shmoo

View on Wikipedia| Shmoo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Publication information | |

| First appearance | 1948 |

| Created by | Al Capp |

The shmoo (plural: shmoos, also shmoon) is a fictional cartoon creature created by Al Capp, which first appeared in the comic strip Li'l Abner on August 31, 1948. The character created a fad that lasted into the 1950s, including merchandise, songs, fan clubs, and appearances on magazine covers. The parable of the shmoo has been interpreted in many different ways, both at the time and in later analysis.

Origins

[edit]Al Capp offered his version of the origin of the Shmoo in a wryly satirical article, "I Don't Like Shmoos", in Cosmopolitan (June 1949):

I was driving from New York City to my farm in New Hampshire. The top of my car was down, and on either side of me I could see the lush and lovely New England countryside... It was the good earth at its generous summertime best, offering gifts to all. And the thought that came to me was this: Here we have this great and good and generous thing—the Earth. It's eager to give us everything we need. All we have to do is just let it alone, just be happy with it.

Cartoonists don't think like people. They think in pictures. Little pictures that will fit into a comic strip. And so, in my mind, I reduced the Earth... down to the size of a small critter that would fit into the Li'l Abner strip—and it came out a Shmoo... I didn't have any message—except that it's good to be alive. The Shmoo didn't have any social significance; it is simply a juicy li'l critter that gives milk and lays eggs... When you look at one as though you'd like to eat it, it dies of sheer ecstasy. And if one really loves you, it'll lay you a cheesecake—although this is quite a strain on its li'l innards...

I thought it was a perfectly ordinary little story, but when it appeared in newspapers, all hell broke loose! Life, in an editorial, hailed the Shmoo as the very symbol and spirit of free enterprise. Time said I'd invented a new era of enlightened management-employee relationship, (they called it Capp-italism). The Daily Worker cussed me out as a Tool of the Bosses, and denounced the Shmoo as the Opium of the Masses...

Capp introduced many other allegorical creatures in Li'l Abner over the years—including Bald Iggles, Kigmies, Nogoodniks, Mimikniks, the Money Ha-Ha, Shminks, Abominable Snow-Hams, Gobbleglops, Shtunks and Bashful Bulganiks, among others. Each one highlighted another disquieting facet of human nature—but none have ever had quite the same cultural impact as the Shmoo. According to publisher Denis Kitchen: "For the rest of his career Capp got countless letters [from] people begging him to bring the Shmoo back. Periodically he would do it but each time it ended the same way—with the Shmoo being too good for humanity, and he had to essentially exterminate them again. But there was always one or two who would survive for future plot twists..."

Etymology

[edit]The origin of Capp's word "shmoo" has been the subject of linguistic consideration by scholars for decades. Academics Arthur Asa Berger and Allan H. Orrick of Johns Hopkins University speculated by that shmoo was a thinly veiled phallic symbol, and that the name derives from Yiddish schmuck (schmo) meaning ‘male genitalia’ or a ‘fool, contemptuous person’.[1][2] Even prior to Berger and Orrick's explanation, Thomas Pyles at University of Florida had favored the shmuck etymology over the derivation from the Yiddish schmu (‘profit’), suggested by Leo Spitzer.[a][3]

Spitzer noted the shmoo's providential characteristics (providing eggs and milk) in arguing his hypothesis, further explaining that in Yiddish schmu specifically connoted "illicit profit", and that the word also giving rise to term schmus ‘tale, gossip’, whose verb form schmusen or ‘shmoosing’ (schmooze) has become familiar even to non-Jews.[4] Lilian Mermin Feinsilver assessed this association with shmu ‘illicit profit’ as "pertinent", together with the observation that shmue was a taboo Yiddish term for the uterus.[5]

It is one of many Yiddish slang variations that would find their way into Li'l Abner. Revealing an important key to the story, Al Capp wrote that the Shmoo metaphorically represented the limitless bounty of the Earth in all its richness—in essence, Mother Nature herself. In Li'l Abner's words, "Shmoos hain't make believe. The hull [whole] earth is one!!"

Analysis

[edit]The Shmoo, any literate person must know, was one of history's most brilliant utopian satires.

— The Baltimore Sun, 2002[6]

"Capp is at his allegorical best in the epics of the Shmoos, and later, the Kigmies", wrote comic strip historian Jerry Robinson[7] "Shmoos are the world's most amiable creatures, supplying all man's needs. Like a fertility myth gone berserk, they reproduced so prodigiously they threatened to wreck the economy"—if not western civilization as we know it, and ultimately society itself.

Superficially, the Shmoo story concerns a cuddly creature that desires nothing more than to be a boon to humans. Although initially Capp denied or avoided discussion of any satirical intentions ("If the Shmoo fits", he proclaimed, "wear it!"),[8] he was widely seen to be using clever subtext. The story has social, ethical, and philosophical implications that continue to invite analysis into the 21st Century.[9][10][11][12][13] During the remainder of his life, Capp was seldom interviewed without reference to the nature of the Shmoo story.

The mythic tale ends on a deliberately ironic note. Shmoos are officially declared a menace, and systematically hunted down and slaughtered—because they were deemed "bad for business". The much-copied story line was a parable that was interpreted in many different ways at the outset of the Cold War. Al Capp was even invited to go on a radio show to debate socialist Norman Thomas on the effect of the Shmoo on modern capitalism.

"After it came out both the left and the right attacked the Shmoo", according to publisher Denis Kitchen. "Communists thought he was making fun of socialism and Marxism. The right wing thought he was making fun of capitalism and the American way. Capp caught flak from both sides.[14] For him it was an apolitical morality tale about human nature... I think [the Shmoo] was one of those bursts of genius. He was a genius, there's no question about that."[15]

Reception

[edit]The Shmoo inspired hundreds of "Shmoo clubs" all over North America. College students—who had made Capp's invented idea of the Sadie Hawkins dance a universally adopted tradition—flocked to the Shmoo as well. One school, the University of Bridgeport, even launched the "American Society for the Advancement of the Shmoo" in early 1949.[16]

Licensing history

[edit]Of course, it was merchandised to death. I think they even had shmoo toilet seats.

— Al Capp, Cartoonist PROfiles #37, March 1978

An unexpected—and virtually unprecedented—postwar merchandising phenomenon followed Capp's introduction of the Shmoo in Li'l Abner. As in the strip, shmoos suddenly appeared to be everywhere in 1949 and 1950—including a Time cover story. They also garnered nearly a full page of coverage (under "Economics") in the Time International section. Major articles also ran in Newsweek, Life, The New Republic, and countless other publications and newspapers. Virtually overnight, as a Life headline put it, "The U.S. Becomes Shmoo-Struck!"[17]

Toys and consumer products

[edit]

Shmoo dolls, clocks, watches, jewelry, earmuffs, wallpaper, fishing lures, air fresheners, soap, ice cream, balloons, ashtrays, toys, games, Halloween masks, salt and pepper shakers, decals, pinbacks, tumblers, coin banks, greeting cards, planters, neckties, suspenders, belts, curtains, fountain pens, and other shmoo paraphernalia were produced. A garment factory in Baltimore turned out a whole line of shmoo apparel, including "Shmooveralls". In 1948, people danced to the Shmoo Rhumba and the Shmoo Polka. The Shmoo briefly entered everyday language through such phrases as "What's Shmoo?" and "Happy Shmoo Year!"[18]

Close to a hundred licensed shmoo products from 75 different manufacturers were produced in less than a year, some of which sold five million units each.[19] In a single year, shmoo merchandise generated more than $25 million in sales in 1948 dollars (equivalent to $327 million in 2024).[20]

There had never previously been anything like it. Comparisons to contemporary cultural phenomena are inevitable. But modern crazes are almost always due to massive marketing campaigns by large media corporations, and are generally aimed at the youth market. The Shmoo phenomenon arose immediately, spontaneously and solely from cartoonist Al Capp's daily comic strip—and it appealed widely to Americans of all ages. Forty million people read the original 1948 Shmoo story, and Capp's already considerable readership roughly doubled following the overwhelming success of the Shmoo...

— Denis Kitchen

The Shmoo was so popular it even replaced Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse as the face of the Children's Savings Bond, issued by the U.S. Treasury Department in 1949. The valid document was colorfully illustrated with Capp's character, and promoted by the Federal Government of the United States with a $16 million advertising campaign budget. According to one article at the time, the Shmoo showed "Thrift, loyalty, trust, duty, truth, and common cents [that] add up to aid to his nation". Al Capp accompanied President Harry S. Truman at the bond's unveiling ceremony.[21]

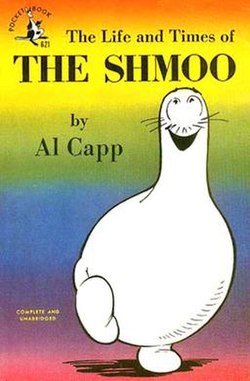

Comic books and reprints

[edit]The Life and Times of the Shmoo (1948), a paperback collection of the original sequence, was a bestseller for Simon & Schuster and became the first cartoon book to achieve serious literary attention.[22] Distributed to small town magazine racks, it sold 700,000 copies in its first year of publication alone. It was reviewed coast to coast alongside Dwight Eisenhower's Crusade in Europe (the other big publication at the time).

The original book and its sequel, The Return of the Shmoo (1959), have been collected in print many times since—most recently in 2002—always to high sales figures.[20]

There was also a separate line of comic books, Al Capp's Shmoo Comics (featuring Washable Jones), published by the Capp family-owned Toby Press.[23] Comics historian and Li'l Abner expert Denis Kitchen recently edited a complete collection of all five original Shmoo Comics, from 1949 and 1950. The book was published by Dark Horse Comics in 2008. Kitchen edited a second Shmoo-related volume for Dark Horse in 2011, on the history of the character in newspaper strips, collectibles, and memorabilia.[24]

Recordings and sheet music

[edit]Recordings and published sheet music related to the Shmoos include:

- The Shmoo Sings with Earl Rogers (1948) 78 rpm / Allegro

- The Shmoo Club b/w The Shmoo Is Clean, the Shmoo Is Neat with Gerald Marks and Justin Stone (1949) 78 rpm / Music You Enjoy, Inc.[25]

- The Snuggable, Huggable Shmoo b/w The Shmoo Doesn't Cost a Cent with Gerald Marks and Justin Stone (1949) 78 rpm / Music You Enjoy, Inc.[25]

- Shmoo Lesson b/w A Shmoo Can Do Most Anything with Gerald Marks and Justin Stone (1949) 78 rpm / Music You Enjoy, Inc.[25]

- The Shmoo Song (1948) Composed by Jule Styne & John Jacob Loeb / Harvey Music Corp.

- Shmoo Songs (1949) Composed by Gerald Marks / Bristol Music Corp.

- The Kigmy Song (1949) Composed by Joe Rosenield & Fay Tishman / Town and Country Music Co.

Animation and puppetry

[edit]Originally, shmoos were meant to be included in the 1956 Broadway Li'l Abner musical, employing stage puppetry. Reportedly, the idea was abandoned in the development stage by the producers, however, for reasons of practicality. A variation of the character had appeared earlier as a marionette puppet on television. "Shmoozer", a talking shmoo with an anthropomorphic human body, was a recurring sidekick character on Fearless Fosdick, a short-lived puppet series that aired on NBC-TV in 1952.[26]

After Capp's death in 1979, the Shmoo gained its own animated series as part of Fred and Barney Meet the Shmoo, which consisted of reruns of The New Fred and Barney Show mixed with the Shmoo's own cartoons; despite the title the two sets of characters didn't directly "meet" within the show. The characters did meet, however, in the early 1980s Flintstones spin-off The Flintstone Comedy Show. The Shmoo appeared, incongruously, in the segment Bedrock Cops as a police officer alongside part-time officers Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble. Needless to add, this Shmoo had little relationship to the L'il Abner character, other than a superficial appearance. A later Hanna-Barbera venture, The New Shmoo, featured the character as an (inexplicably) shape-shifting mascot of Mighty Mysteries Comics, a group of teens who solve Scooby-Doo-like mysteries. In this series the Shmoo could metamorphose magically into any shape at will — like Tom Terrific. None of these revisionist revivals of the venerable character was particularly successful.

In popular culture

[edit]- Frank Sinatra, who was frequently spoofed by Al Capp in Li'l Abner, has a line in the MGM musical On the Town (1949) about cops "multiplyin' like shmoos!"

- Florence King refers to owning a ceramic shmoo, which she threw out of her window after reading the books of Ayn Rand.

- In the 1990 movie Book of Love, the character Crutch wins a stuffed shmoo at a carnival.

- In the M*A*S*H television episode "Who Knew?", Colonel Potter (played by Harry Morgan) displays an inflatable shmoo toy in his office that he purchased for his grandson.

- In Larry Niven's Known Space stories, an alien species known as the Bandersnatch, also edible and intelligent, is described as being "smooth as a shmoo".

- In the novel The Forge of God by Greg Bear, "Shmoo" is the name humans give to the race of robots that visits Earth, due to their similar shape.

- Some overlapping similarities exist between shmoos and tribbles—the multitudinous alien creatures featured in a 1967 television episode from the original Star Trek. Like shmoos, tribbles also reproduced at such an alarming rate, they threatened ecological disaster. However, David Gerrold—who wrote "The Trouble with Tribbles"—drew his inspiration from an historical event: Australia's environmentally destructive rabbit overpopulation.

- The characters Gleep and Gloop—two protoplastic creatures from the Hanna-Barbera Saturday morning animated cartoon series The Herculoids—were clearly inspired by (and are sometimes mistaken for) shmoos.

- French artists Etienne Chambaud and David Jourdan have written "Economie de l'abondance ou La courte vie et les jours heureux", a new adventure of Jacques le fataliste et son maître from Diderot, based on the discovery by Jacques of the Shmoo.

- In the 2006 film Lucky Number Slevin, the character known only as "The Boss" (played by Morgan Freeman) refers to the Shmoo, recounting its original features as a source of plenty (in a monologue taken from an old Li'l Abner comic).

- The Marxist political philosopher Gerald Cohen used the story of the Shmoo to illustrate his objections to capitalism in an episode of Opinions.[27]

- The Simpsons uses a statue of the Shmoo to replace the giant phallic statue from the film A Clockwork Orange in the episode "Treehouse of Horror XXV".

- In Cartoon Network's The Grim Adventures of Billy & Mandy, the Shmoo is seen dancing during Billy's story in the episode "Billy & Mandy Begins."

- The Shmoo is featured in "Bedrock Cops" as a friend and partner of Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble.

- In all non-Japanese versions of the video game Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, there is an enemy monster called "Schmoo", an homage to the Shmoo. (In the original Japanese version, the monster is instead an obake called "Kyuu," an homage to the protagonist of the manga Obake no Q-tarō.) Schmoos appear in the Forbidden Library and they have a rare chance of dropping the Crissaegrim (Valmanway) upon death, the most powerful weapon in the game.

- During the Soviet Union's blockade of West Berlin, Germany in 1948, candy-filled shmoos were air-dropped to hungry West Berliners from transport planes by America's 17th Military Airport Squadron. The commanders of the Berlin airlift had cabled Capp, requesting the inflatable shmoos as part of Operation: Little Vittles. "When the candy-chocked shmoos were dropped, a near-riot resulted...."[28]

- Shmoos invaded the 1948 presidential election, as challenger Thomas Dewey accused incumbent Harry S. Truman of "promising everything, including the Shmoo!"[29]

- Capp periodically reintroduced the Shmoos in Li'l Abner, sometimes with significant variations. "Bad" Shmoos (called "Nogoodniks") debuted in a series of Sunday strips in 1949.[30] The nasty cousin of the good-natured Shmoo, Nogoodniks were a sickly shade of green, and had "li'l red eyes, sharp yaller teeth, an' a dirty look". Frequently sporting 5 o'clock shadows, eye patches, scars, bandages, and other ruffian attributes—they devoured "good" Shmoos, were the sworn enemies of "hoomanity", and wreaked havoc on Dogpatch.

- In the ABC sitcom The Goldbergs, Beverley Goldberg endearingly refers to her children as Shmoos.

- The product of artist Mark Gonzale, Adidas sells a version of its Trefoil logo (termed the Shmoofoil), that is patterned after the Shmoo.

Eponyms

[edit]

The term "shmoo" has entered the English language, defining highly technical concepts in at least four separate fields of science:

- "Shmoo plot" is a technical term relating to the graphical display of test results in electrical engineering, dating back at least to 1966.[31] The name most likely arose because the shape of the two-dimensional plots often resembled a shmoo. The term is also a verb: to "shmoo" means to run the test.

- In microbiology, the shmoo's uncanny resemblance to budding yeast—combined with its near-limitless usefulness—has led to the character's adoption as a mascot of sorts for scientists studying yeast as a model organism for genetics and cell biology. In fact, the cellular bulge that is produced by a haploid yeast cell as a response to a pheromone from the opposite mating type (either a or α-factor) is referred to as a "shmoo", because cells that are undergoing mating and present this particular structure resemble the cartoon character.[32] The whole process is known to biologists as "shmooing". Shmoos are essential; without them, we would have neither bread nor beer. The word "shmoo" has appeared in nearly 700 science publications since 1974; it is used in labs studying the bread- and beer-making species Saccharomyces cerevisiae.[33]

- Echinoderm biologists use "shmoo" (often misspelled "schmoo") to refer to a very simple, highly derived, blob-shaped larva found in some sea urchins (e.g. Wray 1996[34]).

- The Mouse Head Mesemb, Muiria hortensae, a monotypic genus of succulent plant in the Aizoaceae, is also known as the Shmoo Plant. It is native to a small area of the Succulent Karoo of South Africa.

- In bird collections, skin specimens prepared without bills are often called "shmoos".[35]

- It has been used in discussions of socioeconomics, for instance. In economics, a "widget" is any material good that is produced through labor (extracted, refined, manufactured, or assembled) from a finite resource—in contrast to a "shmoo", which is a material good that reproduces itself and is captured or bred as an economic activity (the original shmoo lives and reproduces without requiring any material sustenance). "If shmoos really existed, they would be a 'free good'." Erik Olin Wright uses the "parable of the shmoo" to introduce discussion of class structure and economics.[36]

- In the field of particle physics, "shmoo" refers to a high energy cosmic ray survey instrument used at the Los Alamos National Laboratory for the Cygnus X-3 Sky Survey performed at the LAMPF (Los Alamos Meson Physics Facility) grounds. At one time, more than one hundred white "shmoo" detectors were sprinkled around the accelerator beamstop area and adjacent mesa to capture subatomic cosmic ray particles emitted from the Cygnus constellation. The detectors housed scintillators and photomultipliers in an array that gave the detector its distinctive shmoo shape. The particle accelerator Tevatron at Fermilab houses superconducting magnets that produce ice formations that also resembled shmoos.[37]

- In medicine, the "Shmoo sign" refers to the appearance of a prominent, rounded left ventricle and dilated aorta on a plain AP chest radiograph, giving the appearance of a Shmoo.[38][39]

Applied conversely, the shmoo has been cited as a hypothetical example of the potential falsifiability of natural selection as a key driving mechanism of biological evolution. That is, such a poorly adapted species could not possibly evolve via natural selection, so if it were to exist, it would falsify the theory.[40]

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Pyles assumed the cartoonist had made an unconscious association with the expletive term, and Spitze also suggested "Al Kapp" (sic.) "may not be [have been] consciously aware" when his mind evoked the Yiddish word schmu. Orrick however sides with the findings of the New York State Joint Legislative that this was a conscious choice of word. Orrick points to one cartoon drawing in which the Shmoo is depicted in a suggestive (phallic) pose, and which bears the caption "Benedick" (Italics is his).

References

[edit]- ^ Berger, Arthur Asa (1970). Li'l Abner: a Study in American Satire. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 116. ISBN 1617034169.

- ^ Orrick, Allan H. (May 1954). "On the Etymology of 'shmoo'". American Speech. 29 (2). Duke University Press: 156. JSTOR 453343.

- ^ Pyles, Thomas (1952). Words and Ways of American English, New York : Random House, apud Orrick (1954)

- ^ Spitzer, Leo (February 1950). "The Shmoo". American Speech. 25 (1). Duke University Press: 69–70. JSTOR 454219.

- ^ Feinsilver, Lilian Mermin (2015) [1980], Dillard, J. L. (ed.), "The Yiddish is Showing", Perspectives on American English, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 9783110813340

- ^ Pakenham, Michael (2002-11-29). "Editor's Choice: The Short Life and Happy Times of the Shmoo, by Al Capp, with an introduction by Harlan Ellison". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2017-05-08.[dead link]

- ^ Robinson, Jerry (1974). The Comics: An Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art. Putnam. ISBN 9780399109379.

- ^ Kanfer, Stefan (Spring 2010). "Exile in Dogpatch: The Curious Neglect of Cartoonist Al Capp". City Journal. Retrieved 2012-12-10.[dead link]

- ^ Berger, Arthur Asa (2004-07-15). Media Analysis Techniques, 3rd ed. Sage Publications, Inc. ISBN 9781412906838. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Funch, Flemming (25 April 2004). "Shmoo Technology". Future Hi. Archived from the original on 2004-10-27. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ "Capp-italist Revolution: Al Capp's Shmoo Offers a Parable of Plenty". Life. 20 December 1948. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Maré, KNS (2002). "The Short Life & Happy Times of the Shmoo by Al Capp; with a foreword by Harlan Ellison". main.nc.us. Mountain Area Information Network. Archived from the original on 2012-06-17. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ "Berkeley Sociology 298 Lecture 4: Class, Exploitation, Oppression; 5 March 2002" (PDF). ssc.wisc.edu. Dept. of Sociology, University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 15, 2006. Retrieved March 25, 2025.

- ^ "Harvest Shmoon". Time. 13 September 1948. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Kitchen, Denis (April 2003). "Everything and the Kitchen Shmoo: Interview with Denis Kitchen" (Interview). Archived from the original on June 23, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ^ | "Interview With Roswell Bud Harris"[dead link]

- ^ "The U.S. Becomes Shmoo-Struck!". Life. 20 September 1948. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ "Al Capp's Shmoo". Essortment.com. 1986-05-16. Archived from the original on 2009-05-22. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Newsweek, 5 September 1949; and Editor & Publisher, 16 July 1949

- ^ a b Kitchen, Denis (2004). "The Shmoo Fact Sheet". Deniskitchen.com. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Larson, T. E. A. (2008-09-10). "The Shmoo Part I". Fishing for History: The History of Fishing and Fishing Tackle. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ "The Miracle of Dogpatch". Time. 27 December 1948. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Thompson, Steven (26 May 2012). "Super Shmoo – Al Capp's Shmoo – 1949". Four-Color Shadows. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ "The Oddly Compelling Interview: Denis Kitchen". I.T.C.H. 6 August 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ a b c Muldavin, Peter (2007). The Complete Guide to Vintage Children's Records. Paducah, Kentucky: Collector Books. pp. 134–135. ISBN 9781574325096.

- ^ "Fearless Fosdick (TV Series 1952– )" – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ "G. A. Cohen – Against Capitalism – Part 1". YouTube. 2011-02-02. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Newsweek, 11 October 1948

- ^ Newsweek, 5 September 1948

- ^ "Bad Shmoos from The Scoop Archive, 24 August 2002". Scoop.diamondgalleries.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Belove, Charles (1966). "The Sensitivity Function in Variability Analysis". IEEE Transactions on Reliability. R-15 (2): 70–76. doi:10.1109/TR.1966.5217603.

- ^ Buchet, Alex (18 December 2010). "Strange Windows: Keeping up with the Goonses (part 3)". The Hooded Utilitarian. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Marshall, Jessica (November 2007). "Stupid Science Word of the Month: Shmoo". Discover.[dead link]

- ^ Wray, Gregory A. (1996). "Parallel Evolution of Nonfeeding Larvae in Echinoids". Systematic Biology. 45 (3): 308–322. doi:10.1093/sysbio/45.3.308.

- ^ Winkler, Kevin (Apr 28, 2000). "Obtaining, preserving, and preparing bird specimens". Journal of Field Ornithology. 71 (2): 250–297. doi:10.1648/0273-8570-71.2.250. S2CID 86281124.

- ^ Wright, Erik Olin (1997). Class Counts: Comparative Studies in Class Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521556460. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Higgins, William S. (June 2012). "Shmoos of the Tevatron" (PDF). Symmetry. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Bell, Daniel J.; Reddy, Sahith; et al. (10 November 2013). "Shmoo Sign". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- ^ Brant, William E.; Helms, Clyde A. (2012-03-20). Fundamentals of Diagnostic Radiology. LWW. ISBN 978-1-60831-911-4.

- ^ Pinker, Steven (1994). "The Big Bang". The Language Instinct. New York: William Morrow. p. 358. ISBN 0-688-12141-1. Dennett, Daniel (1995). "Controversies Contained". Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-684-82471-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Capp, Al, The Life and Times of the Shmoo (1948) Simon & Schuster

- Capp, Al, "There Is a Real Shmoo" (New Republic, 21 March 1949)

- Capp, Al, "I Don't Like Shmoos" (Cosmopolitan, June 1949)

- Al Capp Studios, Al Capp's Shmoo Comics (1949–1950) 5 issues (Toby Press)

- Al Capp Studios, Al Capp's Shmoo in Washable Jones' Travels (1950) (Oxydol premium)

- Al Capp Studios, Washable Jones and the Shmoo (1953) (Toby Press)

- Capp, Al, Al Capp's Bald Iggle: The Life It Ruins May Be Your Own (1956) Simon & Schuster

- Capp, Al, The Return of the Shmoo (1959) Simon & Schuster

- Capp, Al, Charlie Mensuel #2 (March 1969) (A French monthly periodical devoted to comics)

- Capp, Al, The Best of Li'l Abner (1978) Holt, Rinehart & Winston ISBN 0-03-045516-2

- Capp, Al, Li'l Abner: Reuben Award Winner Series Book 1 (1985) Blackthorne

- Capp, Al, Li'l Abner Dailies: 1948 Vol. 14 (1992) Kitchen Sink Press ISBN 0-87816-116-3

- Capp, Al, Li'l Abner Dailies: 1949 Vol. 15 (1992) Kitchen Sink ISBN 0-87816-127-9

- Capp, Al, Li'l Abner Dailies: 1956 Vol. 22 (1995) Kitchen Sink ISBN 0-87816-271-2

- Capp, Al, Li'l Abner Dailies: 1959 Vol. 25 (1997) Kitchen Sink ISBN 0-87816-278-X

- Capp, Al, The Short Life and Happy Times of the Shmoo (2002) Overlook Press ISBN 1-58567-462-1

- Capp, Al, Al Capp's Li'l Abner: The Frazetta Years – 4 volumes (2003, 2004) Dark Horse Comics

- Al Capp Studios, Al Capp's Complete Shmoo: The Comic Books (2008) Dark Horse ISBN 1-59307-901-X

- Capp, Al, Al Capp's Complete Shmoo Vol. 2: The Newspaper Strips (2011) Dark Horse ISBN 1-59582-720-X

External links

[edit]Shmoo

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Creation

Introduction in Li'l Abner

The Shmoo first appeared in Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip on August 31, 1948, marking the debut of a fictional creature destined to become a cultural phenomenon.[2] In the introductory storyline, set in the impoverished hillbilly community of Dogpatch, protagonist Li'l Abner Yokum is drawn by strange sounds into the secluded Valley of the Shmoon, a previously unknown location.[4] There, Abner encounters the Shmoo, a small, white, pear-shaped being lacking arms but featuring short legs and a versatile form that embodies selfless utility toward humans.[5] Upon sighting Abner, the Shmoo immediately expresses adoration, collapsing in ecstasy at human presence, which underscores its core trait of eager service without demand for reciprocity.[2] The creature demonstrates practical value by producing Grade A eggs and milk on request, while willingly sacrificing itself for consumption—yielding meat that tastes like fried chicken or broiled steak depending on preparation method.[4] Additional attributes include rapid asexual reproduction, ensuring boundless supply, and byproduct utility such as leather from its hide, buttons from its eyes, and even entertainment through shape-shifting or companionship that supplants leisure industries.[2] This introduction rapidly escalates as Shmoos multiply and distribute beyond the valley, enabling Dogpatch residents to achieve self-sufficiency and abundance without labor or cost, thereby disrupting local and broader economic structures.[4] Al Capp crafted the Shmoo as a satirical emblem of untapped natural bounty, reflecting postwar optimism while foreshadowing conflicts with vested interests opposed to such unearned prosperity.[2] The sequence captivated over 40 million readers across more than 500 newspapers, igniting immediate merchandise frenzy and media coverage.[2]Etymology and Conceptual Development

The term "shmoo" was coined by American cartoonist Al Capp (1909–1979) for his satirical comic strip Li'l Abner, debuting on August 31, 1948.[6] Its etymological roots remain speculative, with proposed derivations from Yiddish slang such as schmo (a euphemism for schmuck, denoting the penis or a fool) or schmu (illicit profit).[6][7] Capp himself provided no definitive origin in his writings, though he satirically recounted conceiving the creature during a drive, portraying it as an intuitive invention rather than a deliberate linguistic borrowing.[8] Conceptually, the shmoo emerged amid post-World War II economic optimism in the United States, embodying a fantastical ideal of effortless abundance where a single creature could yield milk, eggs, meat, and even fuel upon demand, while deriving ecstasy from serving humans—including dying willingly for consumption.[1] Capp developed the idea as a hyperbolic extension of natural bounty, initially discovered by the strip's protagonist in a hidden valley, to critique unchecked plenty's potential to disrupt labor and markets; shmoos proliferated uncontrollably, rendering paid work obsolete and prompting industrial sabotage for their extermination.[9] This narrative arc evolved over subsequent strips, transforming the shmoo from a benevolent provider into a symbol of dependency, with Capp later reviving variants to explore recurring themes of overreliance on unearned resources.[10] The concept's rapid cultural penetration—spawning merchandise sales exceeding $100 million by 1949—reflected its appeal as a parable of utopian excess, though Capp emphasized its ironic intent over literal endorsement.[2]Description and Traits

Physical Appearance

The Shmoo is depicted in Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip as a small, armless creature with a plump, pear-shaped or bowling pin-like body supported by stubby legs.[2][11] Its form lacks defined arms, a nose, or ears, contributing to its simplistic, blob-like silhouette.[8] The creature features smooth, white skin, sparse whiskers protruding from its lower face, and large, expressive eyes set above a perpetually cheerful mouth.[11][12] These elements give the Shmoo a cuddly, anthropomorphic appearance, often rendered in black-and-white newsprint with minimal shading to emphasize its rounded contours and friendly demeanor.[13] In the original 1948 strips, the Shmoo's body tapers from a broader upper section to a narrower base, evoking a teardrop inverted for upright posture.[2] Subsequent comic book adaptations and merchandise maintained this core design, with variations limited to scale or stylistic flourishes, such as added eyebrows for expressiveness, but preserving the essential armless, leg-supported profile.[13] The absence of complex anatomical details underscores its role as a fantastical, utilitarian being rather than a realistic animal.[12]Abilities and Behaviors

The Shmoo possesses remarkable provisioning abilities, producing Grade A eggs and milk on demand without requiring gestation or external inputs.[2][14] Its flesh adapts in flavor to the consumer's desire, tasting like chicken when fried or steak when broiled, and it willingly expires upon being eyed hungrily, transforming into a ready-to-cook cut of meat.[2][14] Additional utilities include its skin serving as durable leather, eyes functioning as sturdy buttons, and whiskers acting as effective toothpicks.[2] Shmoos reproduce prolifically, multiplying faster than rabbits to ensure an abundant supply for human needs, with even a single pair capable of sustaining a family indefinitely.[2] They exhibit minimal sustenance requirements, thriving on virtually any material including rocks or air, though their primary drive is service rather than self-preservation.[14] In behavior, Shmoos display unconditional devotion to humans, deriving joy from acts of utility and withering from disuse or neglect, as their existence centers on alleviating human toil and want.[2] Armless and pear-shaped, they approach people affectionately, eagerly submitting to consumption or harvest to fulfill needs, and respond to kindness with reciprocal love while recoiling from malice.[14] This sacrificial altruism renders them passive yet endlessly obliging companions in the comic's narrative.[2]Narrative Role

Initial Discovery and Proliferation

In the Li'l Abner comic strip, the Shmoo debuted in a narrative arc commencing in late August 1948, when the protagonist, Li'l Abner Yokum, ventured into the forbidden Valley of the Shmoon near the fictional community of Dogpatch.[8] Drawn by an unexplained mysterious music audible only to him, Abner ignored warnings from the elderly Ol' Man Mose and was hurled into the valley by a gigantic, primitive woman acting as a threshold guardian.[15][16] There, he encountered a reclusive hairy old man who revealed the Shmoos—amorphous, pear-shaped creatures that had existed since the dawn of time, eagerly providing humans with milk, eggs, leather, and meat upon demand, deriving ecstasy from service rather than self-preservation.[17] Abner initially brought a single Shmoo back to Dogpatch, where its utility quickly demonstrated the species' potential to eliminate scarcity by fulfilling all material needs without labor or cost.[2] Shmoos reproduced at an extraordinary rate, surpassing even rabbits in fecundity; a single breeding pair could render a family entirely self-sufficient, laying eggs, yielding milk, and converting into fuel or food instantaneously.[2] This rapid proliferation extended as Abner facilitated their distribution beyond the valley, allowing Shmoos to multiply across Dogpatch and integrate into daily life, where they performed tasks like powering vehicles or providing building materials, thereby upending traditional economic dependencies.[17][16] The unchecked spread of Shmoos soon saturated the region, with populations expanding to the point of abundance that rendered paid work obsolete and challenged industrial production, as the creatures adapted to any desired form or function to serve humanity.[2] In the storyline, this proliferation culminated in societal disruption, prompting external forces to intervene, though initial adoption reflected the Shmoos' innate drive to propagate and please.[17]Societal Impact and Suppression

The introduction of Shmoos into Dogpatch society initially triggered widespread prosperity, as their ability to provide unlimited free essentials—such as milk, eggs, and meat on demand—rendered traditional agriculture and food industries obsolete within the narrative. Families required only a pair of Shmoos to achieve complete self-sufficiency, multiplying faster than rabbits and adapting to human needs without cost or effort, which Capp depicted as eliminating scarcity for basic goods.[2] This shift satirized potential economic upheaval, with the creatures' bounty leading to a collapse in market demand for commodities, as inhabitants no longer purchased or produced them, foreshadowing critiques of dependency on unearned abundance.[13] The proliferation exacerbated tensions with broader societal structures, as the Shmoos' existence undermined wage labor and industrial incentives; Capp illustrated scenes where workers abandoned jobs, viewing the creatures as a direct challenge to the Protestant work ethic and capitalist production. Industries lobbied against them, arguing that free goods eroded motivation and economic vitality, prompting public debates on whether such plenty preserved or destroyed human industriousness.[9] Al Capp himself debated socialist Norman Thomas on radio about the Shmoos' implications for capitalism, highlighting how their narrative role exposed fears of systemic disruption from effortless plenty.[8] Faced with these threats, the U.S. government in the strip declared Shmoos a peril to national security, launching a systematic extermination campaign to safeguard economic order and prevent total societal reconfiguration. Military forces hunted and eradicated the population, framing the action as necessary to avert anarchy from overabundance, with Capp portraying the suppression as a defense of structured inequality over utopian excess.[2] Subsequent reappearances of surviving Shmoos met similar fates, reinforcing the theme that innovations too benevolent for entrenched interests invite institutional backlash.[1] This plot device underscored Capp's commentary on resistance to plenty that bypasses human toil, though he later clarified no rigid economic ideology drove the satire.[18]Interpretations and Analysis

Economic and Political Symbolism

The Shmoo, introduced in Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip on August 31, 1948, embodies economic abundance through its ability to provide essentials like meat, milk, eggs, fuel, and materials without cost or labor, symbolizing the untapped bounty of nature that could render human toil obsolete.[2] In the narrative, Shmoos multiply rapidly—faster than rabbits—ensuring self-sufficiency for any possessor, but this plenitude triggers widespread economic dislocation, as demand for paid goods evaporates and industries such as pork production face collapse under figures like J. Roaringham Fatback, who declares resistance to change that threatens profits.[9] [19] Capp illustrated this by depicting shopkeepers like Softhearted John ruined by free Shmoo alternatives, underscoring how oversupply disrupts scarcity-driven markets and erodes work incentives, with Old Man Mose warning of the paradox that excessive good becomes a "menace" to capitalist structures reliant on perpetual demand.[19] Politically, Capp framed the Shmoo as a metaphor for laissez-faire capitalism's potential, stating in 1949, "All I know about modern capitalism I learned from the Shmoo," portraying it as a creature driven by enlightened self-interest to serve humanity without coercion.[9] Contemporary outlets like Life magazine lauded it as the "symbol and spirit of free enterprise," aligning with post-World War II optimism about American productivity, while Time highlighted its challenge to bourgeois property norms akin to Marxist critiques of abundance.[19] Yet the story's resolution—extermination via "shmooicide squads" orchestrated by vested interests to safeguard the status quo—serves as a satirical jab at how political and corporate powers conspire against disruptive plenty to maintain dependency on existing systems, prefiguring Capp's later conservative shift critiquing government intervention.[9] [2] This duality has invited readings as both a celebration of market-driven prosperity and a caution against utopias that undermine individual agency, though Capp denied leftist utopian intent, emphasizing instead the Shmoo's voluntary altruism as a model for productive liberty.[9]Critiques of Dependency and Government Intervention

The introduction of Shmoos to Dogpatch precipitates a swift societal shift toward dependency, as the creatures' effortless provision of essentials like milk, eggs, and fuel eliminates the need for labor, prompting residents to forsake work in favor of unending leisure and play. This outcome, depicted in Al Capp's 1948 storyline, underscores a core critique: unearned abundance undermines human initiative and productivity, fostering idleness that erodes self-reliance and communal purpose. Capp portrayed the Shmoos' bounty as restoring a pre-lapsarian plenty, yet the immediate consequence—Dogpatchers abandoning farms and jobs for banjo-strumming and hammock-lounging—highlights how dependency on external provision, absent reciprocal effort, destabilizes economic and moral order.[5][20] Subsequent government and corporate intervention amplifies the critique, as powerful interests mobilize to eradicate the Shmoos, framing their existence as an existential threat to industry and employment. Industrial magnate J. Roaringham Fatback, embodying entrenched economic powers, commissions "Shmooicide Squads" armed with machine guns, grenades, and flamethrowers to systematically exterminate the creatures, with complicity from authorities in Lower Slobbovia and implied U.S. governmental acquiescence to preserve market structures. This suppression, executed despite the Shmoos' harmless benevolence, exemplifies how state-backed intervention can collude with private monopolies to enforce artificial scarcity, prioritizing systemic preservation over individual flourishing and innovation. Capp's narrative thus indicts such actions as coercive maintenance of a labor-dependent economy, where abundance is sacrificed to avert disruption to wage systems and profit models dating to 1948.[5][20] Analysts have extended this to broader warnings against welfare policies mirroring Shmoo-like guarantees, arguing that state provisions risk analogous dependency by decoupling sustenance from work, as evidenced by Capp's later public stance: "Anyone who can walk to the welfare office can walk to work." While Capp described the Shmoo as an apolitical emblem of earth's potential bounty, he tacitly endorsed interpretations critiquing over-reliance on handouts, retorting to socialist readings, "If the Shmoo fits, wear it." Empirical parallels appear in post-war prosperity debates, where unchecked provision could hollow out incentives, aligning with first-principles observations that sustained human progress demands effort amid scarcity.[21][22]Alternative and Contemporary Readings

Beyond predominant economic interpretations, the Shmoo has been viewed as a symbol of ecological harmony and natural provision. Al Capp intended the creature to illustrate the earth's capacity to fulfill human needs without abuse, emphasizing that abundance arises from restraint rather than exploitation. This perspective frames the Shmoo as an archetype of sustainable resource use, contrasting with narratives of inevitable scarcity or interventionist policies.[4] In scientific contexts, the Shmoo's form inspired terminology in cell biology. Yeast cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae develop projections resembling the creature during mating, termed "shmoos" for their plump, irregular shape. This adoption, noted as early as the mid-20th century, reflects the character's enduring cultural permeation into empirical observation and research practices. Contemporary analyses repurpose the Shmoo parable to examine disruptions from "free goods" in class dynamics. Sociologist Erik Olin Wright utilized it to demonstrate how uncommodified abundance, akin to welfare provisions, alters market capacities and labor incentives, underscoring the need for class-based scrutiny in economic transitions. Such readings highlight causal tensions between plenty and structured inequality, independent of original political intent.Reception and Immediate Impact

Public Enthusiasm and Fads

The Shmoo, introduced in Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip on August 31, 1948, elicited immediate and fervent public interest, transforming into a nationwide postwar phenomenon that captivated audiences with its whimsical, utilitarian traits.[1] This enthusiasm manifested in widespread mimicry and collectivism, supplanting the prior year's Sparkle Plenty doll as the dominant toy craze and eclipsing established icons like Mickey Mouse in popularity for a period.[23] Fan clubs formed spontaneously, with enthusiasts organizing events and correspondence centered on Shmoo lore, while musical adaptations, including "Shmoo Songs" composed by Gerald Marks and released in 1949, amplified the fervor through radio play and sheet music sales.[2] Merchandising fads proliferated rapidly, encompassing stuffed dolls, clothing, clocks, watches, jewelry, earmuffs, wallpaper, and even fishing lures, marketed aggressively as symbols of postwar abundance.[24] These items fueled a consumer surge, with Shmoo products appearing on everything from apparel to dairy packaging, reflecting a cultural obsession that prompted public displays such as costume parties and community gatherings themed around the creature's benevolent nature.[25] The craze extended to recordings, with 78 rpm discs featuring Shmoo-themed tunes distributed widely, further embedding the character in everyday entertainment.[13] By late 1948, the intensity of public adoption led to overproduction concerns among manufacturers, yet the fad endured into the early 1950s, marked by sustained demand for novelties like nesting dolls and games that encouraged imaginative play aligned with the Shmoo's narrative of effortless provision.[26] This period of Shmoo-mania underscored a rare alignment of comic innovation with mass-market appeal, though Capp later expressed fatigue with the unrelenting hype, reportedly growing weary of the character's ubiquity.[27]Media Coverage and Celebrity Endorsements

The introduction of the Shmoo in Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip on August 31, 1948, sparked immediate and widespread media interest, with newspapers syndicating the strips and reporting on the ensuing public frenzy as readers clamored for depictions of the creature's utility and affability.[2] This coverage amplified the character's reach beyond comic sections, framing it as a cultural event that disrupted everyday routines, such as workers fixating on the panels during breaks.[9] Major national outlets documented the phenomenon prominently; Time magazine featured an article on the Shmoo in its International section dated August 13, 1948, analyzing its economic implications, followed by a cover illustration of Capp alongside Shmoos on November 6, 1950, which highlighted the sustained mania.[2] Similarly, The New York Times reviewed Capp's 1948 compilation The Life and Times of the Shmoo on December 5, 1948, noting its rapid publication as a direct response to demand for preserved strips.[28] The book itself sold approximately 700,000 copies within months, underscoring the media's role in translating comic hype into print sales.[9] Contemporary press reactions emphasized the Shmoo's disruptive appeal, with outlets describing it as an "unprecedented media phenomenon" that dominated conversations from 1948 to 1952, often likening the obsession to prior fads but noting its unique scale in eliciting voluntary submissions of fan art and letters to editors.[2] No prominent celebrity endorsements for the Shmoo appear in verified period accounts, though Capp's broader celebrity status drew admiration from figures like Charlie Chaplin for Li'l Abner's satirical edge, indirectly bolstering the strip's visibility during the Shmoo arc.[29]Commercial Success

Merchandising Boom

The Shmoo, introduced in Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip in August 1948, sparked a rapid proliferation of licensed merchandise that generated over $25 million in sales within its first year, equivalent to substantial economic activity in the post-World War II consumer market.[30][31] This figure encompassed a wide array of products, including plush dolls manufactured by Gund, plastic figurines with internal bells produced under United Feature Syndicate licensing, and novelty items such as salt shakers, planters, and clocks.[32][2] The syndicate, which distributed Li'l Abner, capitalized on the character's instant appeal by issuing licenses to dozens of manufacturers, leading to widespread availability in department stores and toy shops across the United States by late 1948.[33] Demand surged to the point where production struggled to keep pace, with reports of shortages for popular items like stuffed Shmoo toys and apparel, fueling a secondary market among collectors even in the initial months.[32] The merchandising extended beyond toys to household goods, clothing lines, sheet music, and wallpaper patterns featuring the creature's distinctive shape, reflecting its portrayal as a versatile symbol of abundance that resonated with a public eager for escapist consumerism.[2] By early 1949, the boom had elevated the Shmoo to a cultural phenomenon, surpassing sales of some established Disney characters in specific product categories and prompting endorsements from retailers who reported it as their top novelty seller.[31] This commercial explosion was driven by strategic promotion from United Feature Syndicate, which reprinted the original Shmoo storyline as a standalone book in 1948 to sustain hype, alongside aggressive advertising in newspapers and trade publications highlighting the product's family-friendly appeal.[33] The scale of the response underscored the Shmoo's unique narrative hook—its willingness to serve human needs—translating directly into marketable goodwill, though it also raised early concerns among some observers about over-commercialization of comic art.[30]Licensing Revenue and Economic Scale

The introduction of the Shmoo on August 31, 1948, in Li'l Abner triggered an unprecedented merchandising surge, with close to 100 licensed products manufactured by 75 companies within the first year. These items encompassed toys, clothing, household goods, and novelties, capitalizing on the character's instant appeal as a symbol of effortless abundance.[2] Licensing agreements were managed directly by Al Capp's syndicate, ensuring broad distribution while maintaining quality control, which facilitated rapid market penetration across the United States.[30] Merchandise sales exceeded $25 million in the first year alone, equivalent to approximately $300 million in 2023 dollars when adjusted for inflation, marking the era's largest commercial exploitation of a comic strip character.[2][30] Individual products, such as certain toys, achieved sales of up to five million units, underscoring the Shmoo's dominance in consumer markets and briefly supplanting established icons like Mickey Mouse in promotional campaigns, including as the mascot for U.S. Savings Bonds. This revenue stream not only enriched Capp personally but also amplified the comic strip's readership, which doubled to serve around 80 million weekly consumers by late 1948.[2] Economically, the Shmoo phenomenon illustrated the postwar boom in licensed character branding, generating ancillary benefits like increased newspaper circulation and spin-off publications, such as The Life and Times of the Shmoo, which sold over 700,000 copies in its initial print run.[30] The scale rivaled early Disney efforts but was more compressed, with total licensed output rivaling the gross domestic product contributions of small industries in the late 1940s, though sustained demand waned after Capp narrative-killed the creatures in 1949 to curb overexposure. Despite this, the licensing model set precedents for future comic-based enterprises, emphasizing the causal link between cultural virality and fiscal returns in mid-20th-century America.[2]Adaptations and Expansions

Comic Books and Reprints

Following the Shmoo's debut in Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip on August 31, 1948, the character starred in a dedicated comic book series published by Toby Press. Titled Al Capp's Shmoo Comics, the series ran for five issues between 1949 and 1950, featuring standalone adventures produced by Al Capp Studios. These stories expanded on the Shmoo's whimsical traits, introducing elements such as the detective Washable Jones teaming up with the creature, transformations into Super Shmoo, and satirical foes like Frankenshmoo and Fu Manshmoo.[3][34] The comics capitalized on the Shmoo's immediate popularity, blending humor with the creature's edible, shape-shifting nature in self-contained tales that echoed the utopian satire of the original strip. Each issue maintained Capp's style of exaggerated Dogpatch folklore, with the Shmoo often serving as a benevolent force disrupting human schemes or embodying abundance. Production involved ghost artists under Capp's direction, focusing on rapid serialization to meet demand.[3][13] In 2008, comics historian Denis Kitchen edited and curated a comprehensive reprint collection titled Al Capp's Complete Shmoo: The Comic Books, published by Dark Horse Books. This hardcover volume reprinted all five original issues in their entirety, supplemented by rare bonus stories, Shmoo-themed advertisements from the era, and historical context on the series' production. The edition preserved the black-and-white artwork and restored content to highlight the Shmoo's cultural peak, making the material accessible beyond vintage collectors. No further official reprints have been issued since, though individual issues remain available in the secondary market for enthusiasts.[3][13]Animation, Puppetry, and Recordings

The Shmoo was first adapted into animation by Hanna-Barbera Productions in The New Shmoo, a 16-episode Saturday morning series that premiered on NBC on September 22, 1979. In this version, the character left Dogpatch to assist a trio of teenagers—Mickey, Nita, and Billy Joe—in solving crimes and mysteries, with added shape-shifting capabilities not present in the original comic strip. The series emphasized comedic adventure, drawing on the Shmoo's helpful nature while updating it for a youth audience. Later that season, The New Shmoo segments were integrated into the anthology program Fred and Barney Meet the Shmoo, which aired from November 1979 to September 1980 and combined Shmoo stories with Flintstones characters and other Hanna-Barbera content. These animations marked the character's primary screen appearances, reviving interest amid the studio's mystery-solving cartoon trend. Puppetry adaptations of the Shmoo proved unfeasible despite early plans. Producers of the 1956 Broadway musical Li'l Abner initially intended to incorporate shmoos via stage puppetry to depict their whimsical traits, but abandoned the concept due to logistical challenges and concerns over overcrowding the production's scenario. No subsequent puppetry productions featuring the character materialized. Audio recordings of the Shmoo appeared shortly after its 1948 comic debut, capitalizing on the fad through children's music releases. Music You Enjoy, Inc. issued a series of 7-inch, 78 RPM singles under the banner "Songs of the Shmoo" in 1948 and 1949, directed by Justin Stone and featuring simple, educational tunes promoting the character's virtues. Notable examples include "The Shmoo Club" backed with "The Shmoo Is Clean, The Shmoo Is Neat" (1949) and "A Shmoo Lesson" paired with "A Shmoo Can Do Most Anything," which highlighted themes of utility and cleanliness aligned with Al Capp's original portrayal. These vinyl discs, pressed for mass appeal, represented an early merchandising extension without narrative audio dramas or voice acting from the strip's cast.Legacy

Cultural References

In the 1949 MGM musical film On the Town, Frank Sinatra's character Chip references shmoos during a taxi chase scene, singing about police "multiplyin' like shmoos," an early nod to the creature's rapid cultural proliferation just a year after its comic strip debut.[35] The Shmoo appears in dialogue in the 2006 film Lucky Number Slevin, where the crime boss character, played by Morgan Freeman, expounds on its traits from Al Capp's strip to illustrate a point to protagonist Slevin, drawing on its themes of utility and economic disruption.[36] Video games have occasionally homaged the Shmoo, notably with the "Schmoo" enemy in Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (1997), a blob-like monster encountered in the library area, evoking the creature's amorphous form and tying into the game's collection of pop culture Easter eggs.[37]Eponyms and Scientific Applications

In microbiology, the term "shmoo" denotes the characteristic pear-shaped morphological projection formed by haploid cells of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae during mating. Exposed to pheromones from cells of the opposite mating type, these cells arrest the cell cycle, polarize growth toward the pheromone gradient, and extend a shmoo protrusion within about two hours to facilitate fusion and genetic recombination. This nomenclature reflects the projection's visual similarity to Al Capp's fictional Shmoo, introduced in 1948.[38][39] In electronics engineering, particularly semiconductor testing, a "shmoo plot" illustrates an integrated circuit's performance margins by mapping pass/fail regions across two parameters, such as supply voltage and clock frequency. These contour-like plots reveal operating limits, process sensitivities, and failure boundaries, aiding debug and yield optimization. The term, in use since at least 1966, derives from the Shmoo's blob-like, variable form, evoking the irregular shapes often observed in such graphs.[40][41]