Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sex-determining region Y protein

View on Wikipedia

Sex-determining region Y protein (SRY), or testis-determining factor (TDF), is a DNA-binding protein (also known as gene-regulatory protein/transcription factor) encoded by the SRY gene that is responsible for the initiation of male sex determination in therian mammals (placentals and marsupials).[5] SRY is an intronless sex-determining gene on the Y chromosome.[6] Mutations in this gene lead to a range of disorders of sex development with varying effects on an individual's phenotype and genotype.

SRY is a member of the SOX (SRY-like box) gene family of DNA-binding proteins. When complexed with the steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1) protein, SRY acts as a transcription factor that causes upregulation of other transcription factors, most importantly SOX9.[7] Its expression causes the development of primary sex cords, which later develop into seminiferous tubules. These cords form in the central part of the yet-undifferentiated gonad, turning it into a testis. The now-induced Leydig cells of the testis then start secreting testosterone, while the Sertoli cells produce anti-Müllerian hormone.[8] Effects of the SRY gene, which normally take place 6–8 weeks after fetus formation, inhibit the growth of female anatomical structure in males. The gene also contributes towards developing the secondary sexual characteristics of males.[9]

Gene evolution and regulation

[edit]Evolution

[edit]SRY may have arisen from a gene duplication of the X chromosome bound gene SOX3, a member of the SOX family.[10][11] This duplication occurred after the split between monotremes and therians. Monotremes lack SRY and some of their sex chromosomes share homology with bird sex chromosomes.[12] SRY is a quickly evolving gene, and its regulation has been difficult to study because sex determination is not a highly conserved phenomenon within the animal kingdom.[13] Even within marsupials and placentals, which use SRY in their sex determination process, the action of SRY differs between species.[11] The gene sequence also changes; while the core of the gene, the high-mobility group (HMG) box, is conserved between species, other regions of the gene are not.[11] SRY is one of only four genes on the human Y chromosome that have been shown to have arisen from the original Y chromosome.[14] The other genes on the human Y chromosome arose from an autosome that fused with the original Y chromosome.[14]

Regulation

[edit]SRY has little in common with sex determination genes of other model organisms, therefore, mice are the main model research organisms that can be utilized for its study. Understanding its regulation is further complicated because even between mammalian species, there is little protein sequence conservation. The only conserved group in mice and other mammals is the HMG box region that is responsible for DNA binding. Mutations in this region result in sex reversal, where the opposite sex is produced.[15] Because there is little conservation, the SRY promoter, regulatory elements and regulation are not well understood. Within related mammalian groups there are homologies within the first 400–600 base pairs (bp) upstream from the translational start site. In vitro studies of human SRY promoter have shown that a region of at least 310 bp upstream to translational start site are required for SRY promoter function. It has been shown that binding of three transcription factors, steroidogenic factor 1 (SF1), specificity protein 1 (Sp1 transcription factor) and Wilms tumor protein 1 (WT1), to the human promoter sequence, influence expression of SRY.[15]

The promoter region has two Sp1 binding sites, at -150 and -13 that function as regulatory sites. Sp1 is a transcription factor that binds GC-rich consensus sequences, and mutation of the SRY binding sites leads to a 90% reduction in gene transcription. Studies of SF1 have resulted in less definite results. Mutations of SF1 can lead to sex reversal, and deletion can lead to incomplete gonad development. However, it is not clear how SF1 interacts with the SR1 promoter directly.[16] The promoter region also has two WT1 binding sites at -78 and -87 bp from the ATG codon. WT1 is transcription factor that has four C-terminal zinc fingers and an N-terminal Pro/Glu-rich region and primarily functions as an activator. Mutation of the zinc fingers or inactivation of WT1 results in reduced male gonad size. Deletion of the gene resulted in complete sex reversal. It is not clear how WT1 functions to up-regulate SRY, but some research suggests that it helps stabilize message processing.[16] However, there are complications to this hypothesis, because WT1 also is responsible for expression of an antagonist of male development, DAX1, which stands for dosage-sensitive sex reversal, adrenal hypoplasia critical region, on chromosome X, gene 1. An additional copy of DAX1 in mice leads to sex reversal. It is not clear how DAX1 functions, and many different pathways have been suggested, including SRY transcriptional destabilization and RNA binding. There is evidence from work on suppression of male development that DAX1 can interfere with function of SF1, and in turn transcription of SRY by recruiting corepressors.[15]

There is also evidence that GATA binding protein 4 (GATA4) and FOG2 contribute to activation of SRY by associating with its promoter. How these proteins regulate SRY transcription is not clear, but FOG2 and GATA4 mutants have significantly lower levels of SRY transcription.[17] FOGs have zinc finger motifs that can bind DNA, but there is no evidence of FOG2 interaction with SRY. Studies suggest that FOG2 and GATA4 associate with nucleosome remodeling proteins that could lead to its activation.[18]

Function

[edit]During gestation, the cells of the primordial gonad that lie along the urogenital ridge are in a bipotential state, meaning they possess the ability to become either male cells (Sertoli and Leydig cells) or female cells (follicle cells and theca cells). SRY initiates testis differentiation by activating male-specific transcription factors that allow these bipotential cells to differentiate and proliferate. SRY accomplishes this by upregulating SOX9, a transcription factor with a DNA-binding site very similar to SRY's. SOX9 leads to the upregulation of fibroblast growth factor 9 (Fgf9), which in turn leads to further upregulation of SOX9. Once proper SOX9 levels are reached, the bipotential cells of the gonad begin to differentiate into Sertoli cells. Additionally, cells expressing SRY will continue to proliferate to form the primordial testis. This brief review constitutes the basic series of events, but there are many more factors that influence sex differentiation.

Action in the nucleus

[edit]The SRY protein consists of three main regions. The central region encompasses the high-mobility group (HMG) domain, which contains nuclear localization sequences and acts as the DNA-binding domain. The C-terminal domain has no conserved structure, and the N-terminal domain can be phosphorylated to enhance DNA-binding.[16] The process begins with nuclear localization of SRY by acetylation of the nuclear localization signal regions, which allows for the binding of importin β and calmodulin to SRY, facilitating its import into the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, SRY and SF1 (steroidogenic factor 1, another transcriptional regulator) complex and bind to TESCO (testis-specific enhancer of Sox9 core), the testes-specific enhancer element of the Sox9 gene in Sertoli cell precursors, located upstream of the Sox9 gene transcription start site.[7] Specifically, it is the HMG region of SRY that binds to the minor groove of the DNA target sequence, causing the DNA to bend and unwind. The establishment of this particular DNA "architecture" facilitates the transcription of the Sox9 gene.[16] In the nucleus of Sertoli cells, SOX9 directly targets the Amh gene as well as the prostaglandin D synthase (Ptgds) gene. SOX9 binding to the enhancer near the Amh promoter allows for the synthesis of Amh while SOX9 binding to the Ptgds gene allows for the production of prostaglandin D2 (PGD2). The reentry of SOX9 into the nucleus is facilitated by autocrine or paracrine signaling conducted by PGD2.[19] SOX9 protein then initiates a positive feedback loop, involving SOX9 acting as its own transcription factor and resulting in the synthesis of large amounts of SOX9.[16]

SOX9 and testes differentiation

[edit]The SF-1 protein, on its own, leads to minimal transcription of the SOX9 gene in both the XX and XY bipotential gonadal cells along the urogenital ridge. However, binding of the SRY-SF1 complex to the testis-specific enhancer (TESCO) on SOX9 leads to significant up-regulation of the gene in only the XY gonad, while transcription in the XX gonad remains negligible. Part of this up-regulation is accomplished by SOX9 itself through a positive feedback loop; like SRY, SOX9 complexes with SF1 and binds to the TESCO enhancer, leading to further expression of SOX9 in the XY gonad. Two other proteins, FGF9 (fibroblast growth factor 9) and PDG2 (prostaglandin D2), also maintain this up-regulation. Although their exact pathways are not fully understood, they have been proven to be essential for the continued expression of SOX9 at the levels necessary for testes development.[7]

SOX9 and SRY are believed to be responsible for the cell-autonomous differentiation of supporting cell precursors in the gonads into Sertoli cells, the beginning of testes development. These initial Sertoli cells, in the center of the gonad, are hypothesized to be the starting point for a wave of FGF9 that spreads throughout the developing XY gonad, leading to further differentiation of Sertoli cells via the up-regulation of SOX9.[20] SOX9 and SRY are also believed to be responsible for many of the later processes of testis development (such as Leydig cell differentiation, sex cord formation, and formation of testis-specific vasculature), although exact mechanisms remain unclear.[21] It has been shown, however, that SOX9, in the presence of PDG2, acts directly on Amh (encoding anti-Müllerian hormone) and is capable of inducing testis formation in XX mice gonads, indicating it is vital to testes development.[20]

SRY disorders' influence on sex expression

[edit]Embryos are gonadally identical, regardless of genetic sex, until a certain point in development when the testis-determining factor causes male sex organs to develop. A typical male karyotype is XY, whereas a female's is XX. There are exceptions, however, in which SRY plays a major role. Individuals with Klinefelter syndrome inherit a normal Y chromosome and multiple X chromosomes, giving them a karyotype of XXY. Atypical genetic recombination during crossover, when a sperm cell is developing, can result in karyotypes that are not typical for their phenotypic expression.

Most of the time, when a developing sperm cell undergoes crossover during meiosis, the SRY gene stays on the Y chromosome. If the SRY gene is transferred to the X chromosome instead of staying on the Y chromosome, testis development will no longer occur. This is known as Swyer syndrome, characterized by an XY karyotype and a female phenotype. Individuals who have this syndrome have normally formed uteri and fallopian tubes, but the gonads are not functional. Swyer syndrome individuals are usually considered as females.[22] On the other spectrum, XX male syndrome occurs when a body has 46:XX Karyotype and SRY attaches to one of them through translocation. People with XX male syndrome have a XX Karyotype but are male.[23] Individuals with either of these syndromes can experience delayed puberty, infertility, and growth features of the opposite sex they identify with. XX male syndrome expressers may develop breasts, and those with Swyer syndrome may have facial hair.[22][24]

| Klinefelter Syndrome |

|

| Swyer Syndrome |

|

| XX Male Syndrome |

|

While the presence or absence of SRY has generally determined whether or not testis development occurs, it has been suggested that there are other factors that affect the functionality of SRY.[25] Therefore, there are individuals who have the SRY gene, but still develop as females, either because the gene itself is defective or mutated, or because one of the contributing factors is defective.[26] This can happen in individuals exhibiting a XY, XXY, or XX SRY-positive karyotype.

Additionally, other sex determining systems that rely on SRY beyond XY are the processes that come after SRY is present or absent in the development of an embryo. In a normal system, if SRY is present for XY, SRY will activate the medulla to develop gonads into testes. Testosterone will then be produced and initiate the development of other male sexual characteristics. Comparably, if SRY is not present for XX, there will be a lack of the SRY based on no Y chromosome. The lack of SRY will allow the cortex of embryonic gonads to develop into ovaries, which will then produce estrogen, and lead to the development of other female sexual characteristics.[27]

Role in other diseases

[edit]SRY has been shown to interact with the androgen receptor and individuals with XY karyotype and a functional SRY gene can have an outwardly female phenotype due to an underlying androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS).[28] Individuals with AIS are unable to respond to androgens properly due to a defect in their androgen receptor gene, and affected individuals can have complete or partial AIS.[29] SRY has also been linked to the fact that males are more likely than females to develop dopamine-related diseases such as schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease. SRY encodes a protein that controls the concentration of dopamine, the neurotransmitter that carries signals from the brain that control movement and coordination.[30] Research in mice has shown that a mutation in SOX10, an SRY encoded transcription factor, is linked to the condition of Dominant megacolon in mice.[31] This mouse model is being used to investigate the link between SRY and Hirschsprung disease, or congenital megacolon in humans.[31] There is also a link between SRY encoded transcription factor SOX9 and campomelic dysplasia (CD).[32] This missense mutation causes defective chondrogenesis, or the process of cartilage formation, and manifests as skeletal CD.[33] Two thirds of 46,XY individuals diagnosed with CD have fluctuating amounts of male-to-female sex reversal.[32]

Use in Olympic screening

[edit]One of the most controversial uses of this discovery was as a means for sex verification at the Olympic Games, under a system implemented by the International Olympic Committee in 1992. Athletes with an SRY gene were not permitted to participate as females, although all athletes in whom this was "detected" at the 1996 Summer Olympics were ruled false positives and were not disqualified. Specifically, eight female participants (out of a total of 3387) at these games were found to have the SRY gene. However, after further investigation of their genetic conditions, all these athletes were verified as female and allowed to compete. These athletes were found to have either partial or full androgen insensitivity, despite having an SRY gene, making them externally phenotypically female.[34] In the late 1990s, a number of relevant professional societies in United States called for elimination of gender verification, including the American Medical Association, stating that the method used was uncertain and ineffective.[35] Chromosomal screening was eliminated as of the 2000 Summer Olympics,[35][36][37] but this was later followed by other forms of testing based on hormone levels.[38] In March 2025 World Athletics announced it will do cheek swabbing tests for gender eligibility, specifically looking for the SRY gene, but that this would only be a first screen in determining eligibility, so that individuals with CAIS or Swyer's syndrome would not automatically be excluded from female competition.[9]

Ongoing research

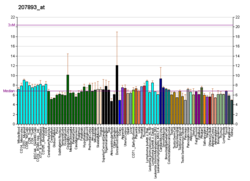

[edit]Despite the progress made during the past several decades in the study of sex determination, the SRY gene, and its protein, work is still being conducted to further understanding in these areas. There remain factors that need to be identified in the sex-determining molecular network, and the chromosomal changes involved in many other human sex-reversal cases are still unknown. Scientists continue to search for additional sex-determining genes, using techniques such as microarray screening of the genital ridge genes at varying developmental stages, mutagenesis screens in mice for sex-reversal phenotypes, and identifying the genes that transcription factors act on using chromatin immunoprecipitation.[16]

Fetal development-knockout models

[edit]One of the knockout models for the SRY gene was done in pigs. Through the use of CRISPR technology the SRY gene was knocked out in male pigs. The target for the CRISPR technology is the high mobility group located on the SRY gene. The research showed that with the absence of SRY, both the internal and external genitalia were reversed. When the piglets were born they were phenotypically male but expressed female genitalia.[39] Another study done on mice used TALEN technology to produce an SRY knockout model. These mice expressed external and internal genitalia as well as a normal female level of circulating testosterone.[40] These mice, despite having XY chromosomes, expressed a normal estrus cycle albeit with reduced fertility. Both of these studies highlighted the role that SRY plays in the development of the testes and other male reproductive organs.

SRY knock-in

[edit]CRISPR-Cas9 technology has been used to insert the SRY gene into XX individuals, thus creating a genetically female organism that is phenotypically male. Only a fragment of 14-kilobases of genomic DNA is necessary for the induction of testis. This alteration in addition to gene drives would allow for the induction of sterility to aid in population control of either unfavorable or invasive species. However, to utilize this knock-in, the relocation of the SRY gene onto the 17th chromosome (autosome) would be most efficient. These transgenic species would then be released into the wild to mate with the natural population, resulting in the creation of predominantly male offspring, thus decreasing reproductive rates. An autosomal SRY knock-in would result in a 75% SRY inheritance rate, whereas a 90% inheritance can be achieved when inserted into the t-complex on the 17th chromosome.[41] Although, previously unsuccessful in mammals, more recent research has found that although thought to only contain single exon for the last 30 years, a second SRY exon has been located named SRY-T .[42]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000184895 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000069036 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Berta P, Hawkins JR, Sinclair AH, Taylor A, Griffiths BL, Goodfellow PN, et al. (November 1990). "Genetic evidence equating SRY and the testis-determining factor". Nature. 348 (6300): 448–50. Bibcode:1990Natur.348..448B. doi:10.1038/348448A0. PMID 2247149. S2CID 3336314.

- ^ Wallis MC, Waters PD, Graves JA (October 2008). "Sex determination in mammals--before and after the evolution of SRY". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 65 (20): 3182–95. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8109-z. PMC 11131626. PMID 18581056. S2CID 31675679.

- ^ a b c Kashimada K, Koopman P (December 2010). "Sry: the master switch in mammalian sex determination". Development. 137 (23): 3921–30. doi:10.1242/dev.048983. PMID 21062860.

- ^ Mittwoch U (October 1988). "The race to be male". New Scientist. 120 (1635): 38–42.

- ^ a b Burrows B (25 March 2025). "World Athletics to introduce cheek swabbing tests for gender eligibility, Sebastian Coe says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 March 2025.

- ^ Katoh K, Miyata T (December 1999). "A heuristic approach of maximum likelihood method for inferring phylogenetic tree and an application to the mammalian SOX-3 origin of the testis-determining gene SRY". FEBS Letters. 463 (1–2): 129–32. Bibcode:1999FEBSL.463..129K. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01621-X. PMID 10601652. S2CID 24519808.

- ^ a b c Bakloushinskaya, I Y (2009). "Evolution of sex determination in mammals". Biology Bulletin. 36 (2): 167–174. Bibcode:2009BioBu..36..167B. doi:10.1134/S1062359009020095. S2CID 36988324.

- ^ Veyrunes F, Waters PD, Miethke P, Rens W, McMillan D, Alsop AE, et al. (June 2008). "Bird-like sex chromosomes of platypus imply recent origin of mammal sex chromosomes". Genome Research. 18 (6): 965–73. doi:10.1101/gr.7101908. PMC 2413164. PMID 18463302.

- ^ Bowles J, Schepers G, Koopman P (November 2000). "Phylogeny of the SOX family of developmental transcription factors based on sequence and structural indicators". Developmental Biology. 227 (2): 239–55. doi:10.1006/dbio.2000.9883. PMID 11071752.

- ^ a b Graves JA (December 2015). "Weird mammals provide insights into the evolution of mammalian sex chromosomes and dosage compensation". Journal of Genetics. 94 (4): 567–74. doi:10.1007/s12041-015-0572-3. PMID 26690510. S2CID 186238659.

- ^ a b c Ely D, Underwood A, Dunphy G, Boehme S, Turner M, Milsted A (November 2010). "Review of the Y chromosome, Sry and hypertension". Steroids. 75 (11): 747–53. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2009.10.015. PMC 2891862. PMID 19914267.

- ^ a b c d e f Harley VR, Clarkson MJ, Argentaro A (August 2003). "The molecular action and regulation of the testis-determining factors, SRY (sex-determining region on the Y chromosome) and SOX9 [SRY-related high-mobility group (HMG) box 9]". Endocrine Reviews. 24 (4): 466–87. doi:10.1210/er.2002-0025. PMID 12920151.

- ^ Knower KC, Kelly S, Harley VR (2003). "Turning on the male--SRY, SOX9 and sex determination in mammals". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 101 (3–4): 185–98. doi:10.1159/000074336. PMID 14684982. S2CID 20940513.

- ^ Zaytouni T, Efimenko EE, Tevosian SG (2011). GATA Transcription Factors in the Developing Reproductive System. Advances in Genetics. Vol. 76. pp. 93–134. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386481-9.00004-3. ISBN 9780123864819. PMID 22099693.

- ^ Sekido R, Lovell-Badge R (January 2009). "Sex determination and SRY: down to a wink and a nudge?". Trends in Genetics. 25 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.008. PMID 19027189.

- ^ a b McClelland K, Bowles J, Koopman P (January 2012). "Male sex determination: insights into molecular mechanisms". Asian Journal of Andrology. 14 (1): 164–71. doi:10.1038/aja.2011.169. PMC 3735148. PMID 22179516.

- ^ Sekido R, Lovell-Badge R (2013). "Genetic control of testis development". Sexual Development. 7 (1–3): 21–32. doi:10.1159/000342221. PMID 22964823.

- ^ a b "Swyer syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "XX Male Syndrome {". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "46,XX testicular disorder of sex development". Genetics Home Reference. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ Polanco JC, Koopman P (February 2007). "Sry and the hesitant beginnings of male development". Developmental Biology. 302 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.049. PMID 16996051.

- ^ Biason-Lauber A, Konrad D, Meyer M, DeBeaufort C, Schoenle EJ (May 2009). "Ovaries and female phenotype in a girl with 46,XY karyotype and mutations in the CBX2 gene". American Journal of Human Genetics. 84 (5): 658–63. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.016. PMC 2680992. PMID 19361780.

- ^ Marieb EN, Hoehn K (2018). Human Anatomy & Physiology (Eleventh ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-0-13-458099-9. OCLC 1004376412.

- ^ Yuan X, Lu ML, Li T, Balk SP (December 2001). "SRY interacts with and negatively regulates androgen receptor transcriptional activity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (49): 46647–54. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108404200. PMID 11585838.

- ^ Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications (2008). "Androgen insensitivity syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Dewing P, Chiang CW, Sinchak K, Sim H, Fernagut PO, Kelly S, et al. (February 2006). "Direct regulation of adult brain function by the male-specific factor SRY". Current Biology. 16 (4): 415–20. Bibcode:2006CBio...16..415D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.017. PMID 16488877. S2CID 5939578.

- ^ a b Herbarth B, Pingault V, Bondurand N, Kuhlbrodt K, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Puliti A, et al. (1998). "Mutation of the Sry-related Sox10 gene in Dominant megacolon, a mouse model for human Hirschsprung disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (9): 5161–5165. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.5161H. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.9.5161. PMC 20231. PMID 9560246.

- ^ a b Pritchett J, Athwal V, Roberts N, Hanley NA, Hanley KP (2011). "Understanding the role of SOX9 in acquired diseases: lessons from development". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 17 (3): 166–174. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2010.12.001. PMID 21237710.

- ^ "OMIM Entry – # 114290 – CAMPOMELIC DYSPLASIA". omim.org. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ "Olympic Gender Testing".

- ^ a b Facius GM (1 August 2004). "The Major Medical Blunder of the 20th Century". Gender Testing. facius-homepage.dk. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2011.[self-published source?]

- ^ Elsas LJ, Ljungqvist A, Ferguson-Smith MA, Simpson JL, Genel M, Carlson AS, et al. (2000). "Gender verification of female athletes". Genetics in Medicine. 2 (4): 249–54. doi:10.1097/00125817-200007000-00008. PMID 11252710.

- ^ Dickinson BD, Genel M, Robinowitz CB, Turner PL, Woods GL (October 2002). "Gender verification of female Olympic athletes". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 34 (10): 1539–42, discussion 1543. doi:10.1097/00005768-200210000-00001. PMID 12370551.

- ^ "IOC Regulations on Female Hyperandrogenism" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. 22 June 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Kurtz S, Lucas-Hahn A, Schlegelberger B, Göhring G, Niemann H, Mettenleiter TC, et al. (January 2021). "Knockout of the HMG domain of the porcine SRY gene causes sex reversal in gene-edited pigs". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (2). Bibcode:2021PNAS..11808743K. doi:10.1073/pnas.2008743118. PMC 7812820. PMID 33443157.

- ^ Kato T, Miyata K, Sonobe M, Yamashita S, Tamano M, Miura K, et al. (November 2013). "Production of Sry knockout mouse using TALEN via oocyte injection". Scientific Reports. 3 (1): 3136. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3.3136K. doi:10.1038/srep03136. PMC 3817445. PMID 24190364.

- ^ Piaggio AJ, Segelbacher G, Seddon PJ, Alphey L, Bennett EL, Carlson RH, et al. (February 2017). "Is It Time for Synthetic Biodiversity Conservation?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 32 (2): 97–107. Bibcode:2017TEcoE..32...97P. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2016.10.016. PMID 27871673.

- ^ Miyawaki S, Kuroki S, Maeda R, Okashita N, Koopman P, Tachibana M (October 2020). "The mouse Sry locus harbors a cryptic exon that is essential for male sex determination". Science. 370 (6512): 121–124. Bibcode:2020Sci...370..121M. doi:10.1126/science.abb6430. PMID 33004521.

Further reading

[edit]- Haqq CM, King CY, Ukiyama E, Falsafi S, Haqq TN, Donahoe PK, et al. (December 1994). "Molecular basis of mammalian sexual determination: activation of Müllerian inhibiting substance gene expression by SRY". Science. 266 (5190): 1494–500. Bibcode:1994Sci...266.1494H. doi:10.1126/science.7985018. PMID 7985018.

- Goodfellow PN, Lovell-Badge R (1993). "SRY and sex determination in mammals". Annual Review of Genetics. 27 (1): 71–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.000443. PMID 8122913.

- Hawkins JR (1993). "Mutational analysis of SRY in XY females". Human Mutation. 2 (5): 347–50. doi:10.1002/humu.1380020504. PMID 8257986. S2CID 43503112.

- Harley VR (2002). "The Molecular Action of Testis-Determining Factors SRY and SOX9". The Genetics and Biology of Sex Determination. Novartis Foundation Symposia. Vol. 244. pp. 57–66, discussion 66–7, 79–85, 253–7. doi:10.1002/0470868732.ch6. ISBN 978-0-470-86873-7. PMID 11990798.

- Jordan BK, Vilain E (2002). "SRY and the Genetics of Sex Determination". Pediatric Gender Assignment. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 511. pp. 1–13, discussion 13–4. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0621-8_1. ISBN 978-1-4613-5162-7. PMID 12575752.

- Oh HJ, Lau YF (March 2006). "KRAB: a partner for SRY action on chromatin". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 247 (1–2): 47–52. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.011. PMID 16414182. S2CID 19870331.

- Polanco JC, Koopman P (February 2007). "Sry and the hesitant beginnings of male development". Developmental Biology. 302 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.049. PMID 16996051.

- Hawkins JR, Taylor A, Berta P, Levilliers J, Van der Auwera B, Goodfellow PN (February 1992). "Mutational analysis of SRY: nonsense and missense mutations in XY sex reversal". Human Genetics. 88 (4): 471–4. doi:10.1007/BF00215684. PMID 1339396. S2CID 9332496.

- Hawkins JR, Taylor A, Goodfellow PN, Migeon CJ, Smith KD, Berkovitz GD (November 1992). "Evidence for increased prevalence of SRY mutations in XY females with complete rather than partial gonadal dysgenesis". American Journal of Human Genetics. 51 (5): 979–84. PMC 1682856. PMID 1415266.

- Ferrari S, Harley VR, Pontiggia A, Goodfellow PN, Lovell-Badge R, Bianchi ME (December 1992). "SRY, like HMG1, recognizes sharp angles in DNA". The EMBO Journal. 11 (12): 4497–506. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05551.x. PMC 557025. PMID 1425584.

- Jäger RJ, Harley VR, Pfeiffer RA, Goodfellow PN, Scherer G (December 1992). "A familial mutation in the testis-determining gene SRY shared by both sexes". Human Genetics. 90 (4): 350–5. doi:10.1007/BF00220457. PMID 1483689. S2CID 19470332.

- Vilain E, McElreavey K, Jaubert F, Raymond JP, Richaud F, Fellous M (May 1992). "Familial case with sequence variant in the testis-determining region associated with two sex phenotypes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 50 (5): 1008–11. PMC 1682588. PMID 1570829.

- Müller J, Schwartz M, Skakkebaek NE (July 1992). "Analysis of the sex-determining region of the Y chromosome (SRY) in sex reversed patients: point-mutation in SRY causing sex-reversion in a 46,XY female". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 75 (1): 331–3. doi:10.1210/jcem.75.1.1619028. PMID 1619028.

- McElreavey KD, Vilain E, Boucekkine C, Vidaud M, Jaubert F, Richaud F, et al. (July 1992). "XY sex reversal associated with a nonsense mutation in SRY". Genomics. 13 (3): 838–40. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(92)90164-N. PMID 1639410.

- Sinclair AH, Berta P, Palmer MS, Hawkins JR, Griffiths BL, Smith MJ, et al. (July 1990). "A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif". Nature. 346 (6281): 240–4. Bibcode:1990Natur.346..240S. doi:10.1038/346240a0. PMID 1695712. S2CID 4364032.

- Berkovitz GD, Fechner PY, Zacur HW, Rock JA, Snyder HM, Migeon CJ, et al. (November 1991). "Clinical and pathologic spectrum of 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis: its relevance to the understanding of sex differentiation". Medicine. 70 (6): 375–83. doi:10.1097/00005792-199111000-00003. PMID 1956279. S2CID 37972412.

- Berta P, Hawkins JR, Sinclair AH, Taylor A, Griffiths BL, Goodfellow PN, et al. (November 1990). "Genetic evidence equating SRY and the testis-determining factor". Nature. 348 (6300): 448–50. Bibcode:1990Natur.348..448B. doi:10.1038/348448A0. PMID 2247149. S2CID 3336314.

- Jäger RJ, Anvret M, Hall K, Scherer G (November 1990). "A human XY female with a frame shift mutation in the candidate testis-determining gene SRY". Nature. 348 (6300): 452–4. Bibcode:1990Natur.348..452J. doi:10.1038/348452a0. PMID 2247151. S2CID 4326539.

- Ellis NA, Goodfellow PJ, Pym B, Smith M, Palmer M, Frischauf AM, et al. (January 1989). "The pseudoautosomal boundary in man is defined by an Alu repeat sequence inserted on the Y chromosome". Nature. 337 (6202): 81–4. Bibcode:1989Natur.337...81E. doi:10.1038/337081a0. PMID 2909893. S2CID 2890077.

- Whitfield LS, Hawkins TL, Goodfellow PN, Sulston J (May 1995). "41 kilobases of analyzed sequence from the pseudoautosomal and sex-determining regions of the short arm of the human Y chromosome". Genomics. 27 (2): 306–11. doi:10.1006/geno.1995.1047. PMID 7557997.

- Délot EC, Vilain EJ (1993). "Nonsyndromic 46,XX Testicular Disorders/Differences of Sex Development". In Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al. (eds.). GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301589.

External links

[edit]- Genes,+sry at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Sex-Determining+Region+Y+Protein at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- OMIM entries on 46,XX Testicular Disorder of Sex Development

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Human Sex-determining region Y protein