Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

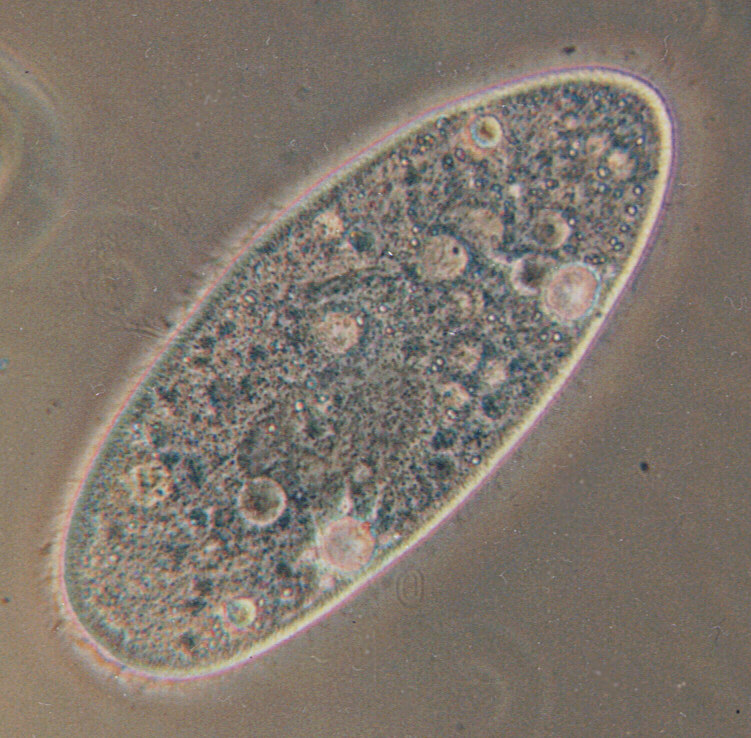

Paramecium

View on Wikipedia

| Paramecium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Paramecium aurelia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Sar |

| Clade: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Ciliophora |

| Class: | Oligohymenophorea |

| Order: | Peniculida |

| Family: | Parameciidae |

| Genus: | Paramecium Müller, 1773 |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

Paramecium (/ˌpærəˈmiːs(i)əm/ PARR-ə-MEE-s(ee-)əm, /-siəm/ -see-əm, plural "paramecia" only when used as a vernacular name)[2] is a genus of eukaryotic, unicellular ciliates, widespread in freshwater, brackish, and marine environments. Paramecia are often abundant in stagnant basins and ponds. Because some species are readily cultivated and easily induced to conjugate and divide, they have been widely used in classrooms and laboratories to study biological processes. Paramecium species are commonly studied as model organisms of the ciliate group and have been characterized as the "white rats" of the phylum Ciliophora.[3]

Historical background

[edit]

Paramecium were among the first ciliates to be observed by microscopists, in the late 17th century. They were most likely known to the Dutch pioneer of protozoology, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, and were clearly described by his contemporary Christiaan Huygens in a letter from 1678.[4] The earliest known illustration of a Paramecium species was published anonymously in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1703.[5]

In 1718, the French mathematics teacher and microscopist Louis Joblot published a description and illustration of a microscopic poisson (fish), which he discovered in an infusion of oak bark in water. Joblot gave this creature the name "Chausson", or "slipper", and the phrase "slipper animalcule" remained in use as a colloquial epithet for Paramecium, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.[6]

The name "Paramecium" – constructed from the Greek παραμήκης (paramēkēs, "oblong") – was coined in 1752 by the English microscopist John Hill, who applied the name generally to "Animalcules which have no visible limbs or tails, and are of an irregularly oblong figure."[7] In 1773, O. F. Müller, the first researcher to place the genus within the Linnaean system of taxonomy, adopted the name Paramecium but changed the spelling to Paramæcium.[8] In 1783, Johann Hermann changed the spelling once more, to Paramœcium.[9] C. G. Ehrenberg, in a major study of the infusoria published in 1838, restored Hill's original spelling for the name, and most researchers have followed his lead.[10]

Description

[edit]

Species of Paramecium range in size from 0.06 mm to 0.3 mm in length. Cells are typically ovoid, elongate, or foot- or cigar-shaped.

The body of the cell is enclosed by a stiff but elastic structure called the pellicle. The pellicle consists of an outer cell membrane (plasma membrane), a layer of flattened membrane-bound sacs called alveoli, and an inner membrane called the epiplasm. The pellicle is not smooth, but textured with hexagonal or rectangular depressions. Each of these polygons is perforated by a central aperture through which a single cilium projects. Between the alveolar sacs of the pellicle, most species of Paramecium have closely spaced spindle-shaped trichocysts, explosive organelles that discharge thin, non-toxic filaments, often used for defensive purposes.[11][12]

Typically, an anal pore (cytoproct) is located on the ventral surface, in the posterior half of the cell. In all species, there is a deep oral groove running from the anterior of the cell to its midpoint. This is lined with inconspicuous cilia which beat continuously, drawing food into the cell.[13] Paramecium are primarily heterotrophic, feeding on bacteria and other small organisms. A few species are mixotrophs, deriving some nutrients from endosymbiotic algae (chlorella) carried in the cytoplasm of the cell.[14]

Osmoregulation is carried out by contractile vacuoles, which actively expel water from the cell to compensate for fluid absorbed by osmosis from its surroundings.[15] The number of contractile vacuoles varies depending on the species.[13]

Movement

[edit]A Paramecium propels itself by whip-like movements of the cilia, which are arranged in tightly spaced rows around the outside of the body. The beat of each cilium has two phases: a fast "effective stroke," during which the cilium is relatively stiff, followed by a slow "recovery stroke," during which the cilium curls loosely to one side and sweeps forward in a counter-clockwise fashion. The densely arrayed cilia move in a coordinated fashion, with waves of activity moving across the "ciliary carpet," creating an effect sometimes likened to that of the wind blowing across a field of grain.[16]

The Paramecium spirals through the water as it progresses. When it happens to encounter an obstacle, the "effective stroke" of its cilia is reversed and the organism swims backward for a brief time, before resuming its forward progress. This is called the avoidance reaction. If it runs into the solid object again, it repeats this process, until it can get past the object.[17]

It has been calculated that a Paramecium expends more than half of its energy in propelling itself through the water.[18] This ciliary method of locomotion has been found to be less than 1% efficient. This low percentage is nevertheless close to the maximum theoretical efficiency that can be achieved by an organism equipped with cilia as short as those of the members of Paramecium.[19]

Gathering food

[edit]

Paramecium feed on microorganisms such as bacteria, algae, and yeasts. To gather food, the Paramecium makes movements with cilia to sweep prey organisms, along with some water, through the oral groove (vestibulum, or vestibule), and into the cell. The food passes from the cilia-lined oral groove into a narrower structure known as the buccal cavity (gullet). From there, food particles pass through a small opening called the cytostome, or cell mouth, and move into the interior of the cell. As food enters the cell, it is gathered into food vacuoles, which are periodically closed off and released into the cytoplasm, where they begin circulating through the cell body by the streaming movement of the cell contents, a process called cyclosis or cytoplasmic streaming. As a food vacuole moves along, enzymes from the cytoplasm enter it, to digest the contents. As enzymatic digestion proceeds, the vacuole contents become more acidic. Within five minutes of a vacuole's formation, the pH of its contents drops from 7 to 3.[20] As digested nutrients pass into the cytoplasm, the vacuole shrinks. When the fully digested vacuole reaches the anal pore, it ruptures, expelling its waste contents outside the cell.[21][22][23]

Symbiosis

[edit]Some species of Paramecium form mutualistic relationships with other organisms. Paramecium bursaria and Paramecium chlorelligerum harbour endosymbiotic green algae, from which they derive nutrients and a degree of protection from predators such as Didinium nasutum.[24][25] Numerous bacterial endosymbionts have been identified in species of Paramecium.[26] Some intracellular bacteria, known as kappa particles, give Paramecium the ability to kill other strains of Paramecium that lack kappa particles.[26]

Genome

[edit]The genome of the species Paramecium tetraurelia has been sequenced, providing evidence for three whole-genome duplications.[27]

In some ciliates, like Stylonychia and Paramecium, only UGA is decoded as a stop codon, while UAG and UAA are reassigned as sense codons (that is, codons that code for standard amino acids), coding for the amino acid glutamic acid.[28]

Learning

[edit]The question of whether Paramecium exhibit learning has been the object of a great deal of experimentation, yielding equivocal results. However, a study published in 2006 seems to show that Paramecium caudatum may be trained, through the application of a 6.5 volt electric current, to discriminate between brightness levels.[29] This experiment has been cited as a possible instance of cell memory, or epigenetic learning in organisms with no nervous system.[30]

Reproduction and sexual phenomena

[edit]Reproduction

[edit]Like all ciliates, Paramecium have a dual nuclear apparatus, consisting of a polyploid macronucleus, and one or more diploid micronuclei. The macronucleus controls non-reproductive cell functions, expressing the genes needed for daily functioning. The micronucleus is the generative, or germline nucleus, containing the genetic material that is passed along from one generation to the next.[31]

Paramecium reproduction is asexual, by binary fission, which has been characterized as "the sole mode of reproduction in ciliates" (conjugation being a sexual phenomenon, not directly resulting in increase of numbers).[3][32] During fission, the macronucleus splits by a type of amitosis, and the micronuclei undergo mitosis. The cell then divides transversally, and each new cell obtains a copy of the micronucleus and the macronucleus.[3]

Fission may occur spontaneously, in the course of the vegetative cell cycle. Under certain conditions, it may be preceded by self-fertilization (autogamy),[33] or it may immediately follow conjugation, in which Paramecium of compatible mating types fuse temporarily and exchange genetic material.

Conjugation

[edit]In ciliates such as Paramecium, conjugation is a sexual phenomenon that results in genetic recombination and nuclear reorganization within the cell.[31][26] During conjugation, two Paramecium of a compatible mating type come together and form a bridge between their cytoplasms. Their respective micronuclei undergo meiosis, and haploid micronuclei are exchanged over the bridge. Following conjugation, the cells separate. The old macronuclei are destroyed, and both post-conjugants form new macronuclei, by amplification of DNA in their micronuclei.[31] Conjugation is followed by one or more "exconjugant divisions."[34]

In Paramecium caudatum, the stages of conjugation are as follows (see diagram at right):

- Compatible mating strains meet and partly fuse

- The micronuclei undergo meiosis, producing four haploid micronuclei per cell.

- Three of these micronuclei disintegrate. The fourth undergoes mitosis.

- The two cells exchange a micronucleus.

- The cells then separate.

- The micronuclei in each cell fuse, forming a diploid micronucleus.

- Mitosis occurs three times, giving rise to eight micronuclei.

- Four of the new micronuclei transform into macronuclei, and the old macronucleus disintegrates.

- Binary fission occurs twice, yielding four identical daughter cells.

Aging

[edit]In the asexual fission phase of growth, during which cell divisions occur by mitosis rather than meiosis, clonal aging occurs leading to a gradual loss of vitality. In some species, such as the well studied Paramecium tetraurelia, the asexual line of clonally aging Paramecium loses vitality and expires after about 200 fissions if the cells fail to undergo autogamy or conjugation. The basis for clonal aging was clarified by transplantation experiments of Aufderheide in 1986.[35] When macronuclei of clonally young Paramecium were injected into Paramecium of standard clonal age, the lifespan (clonal fissions) of the recipient was prolonged. In contrast, transfer of cytoplasm from clonally young Paramecium did not prolong the lifespan of the recipient. These experiments indicated that the macronucleus, rather than the cytoplasm, is responsible for clonal aging. Other experiments by Smith-Sonneborn,[36] Holmes and Holmes,[37] and Gilley and Blackburn[38] demonstrated that, during clonal aging, DNA damage increases dramatically.[39] Thus, DNA damage in the macronucleus appears to be the cause of aging in P. tetraurelia. In this single-celled protist, aging appears to proceed as it does in multicellular eukaryotes, as described in DNA damage theory of aging.

Meiosis and rejuvenation

[edit]When clonally aged P. tetraurelia are stimulated to undergo meiosis in association with either conjugation or automixis, the genetic descendants are rejuvenated, and are able to have many more mitotic binary fission divisions. During conjugation or automixis, the micronuclei of the cell(s) undergo meiosis, the old macronucleus disintegrates, and a new macronucleus is formed by replication of the micronuclear DNA that had recently undergone meiosis. There is apparently little, if any, DNA damage in the new macronucleus. These findings further support the idea that clonal aging is due, in large part, to a progressive accumulation of DNA damage; and that rejuvenation is due to the repair of this damage in the micronucleus during meiosis. Meiosis appears to be an adaptation for DNA repair and rejuvenation in P. tetraurelia.[40] In P. tetraurelia, CtlP protein is a key factor needed for the completion of meiosis during sexual reproduction and recovery of viable sexual progeny.[40] The CtlP and Mre11 nuclease complex are essential for accurate processing and repair of double-strand breaks during homologous recombination.[40]

The adaptive benefit of meiosis and self-fertilization in response to starvation appears to be independent of the generation of any new genetic variation in P. tetraurelia.[41] This observation suggests that the underlying molecular mechanism of meiosis provides a fitness advantage regardless of any concomitant effect of sex on genetic diversity.[41][42]

Video gallery

[edit]-

Paramecium bursaria, a species with symbiotic algae

-

Paramecium putrinum

-

Paramecium binary fission

-

Paramecium in conjugation

-

Paramecium caudatum

List of species

[edit]Paramecium aurelia species complex:

- Paramecium primaurelia

- Paramecium biaurelia

- Paramecium triaurelia

- Paramecium tetraurelia

- Paramecium pentaurelia

- Paramecium sexaurelia

- Paramecium septaurelia

- Paramecium octaurelia

- Paramecium novaurelia

- Paramecium decaurelia

- Paramecium undecaurelia

- Paramecium dodecaurelia

- Paramecium tredecaurelia

- Paramecium quadecaurelia

- Paramecium sonneborni

Other species:

- Paramecium buetschlii

- Paramecium bursaria

- Paramecium calkinsi

- Paramecium caudatum

- Paramecium chlorelligerum

- Paramecium duboscqui

- Paramecium grohmannae

- Paramecium jenningsi

- Paramecium multimicronucleatum

- Paramecium nephridiatum

- Paramecium polycaryum

- Paramecium putrinum

- Paramecium schewiakoffi

- Paramecium woodruffi

References

[edit]- ^ GBIF

- ^ "paramecium". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b c Lynn, Denis (2008). The Ciliated Protozoa: Characterization, Classification, and Guide to the Literature. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 30. ISBN 9781402082399.

- ^ Dobell, Clifford (1932). Antony van Leeuwenhoek and his "Little Animals" (1960 ed.). New York: Dover. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-486-60594-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Dolan, John R. (2019-08-01). "Unmasking "The Eldest Son of The Father of Protozoology": Charles King". Protist. 170 (4): 374–384. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2019.07.002. ISSN 1434-4610. PMID 31479910.

- ^ Joblot, Louis (1718). Description et usages de Plusieurs Nouveaux Microscopes, tant simple que composez (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: Jacques Collombat. p. 79.

- ^ Hill, John (1752). An History of Animals. Paris: Thomas Osborne. p. 5.

- ^ Müller, Otto Frederik; Müller, Otto Frederik (1773). Vermivm terrestrium et fluviatilium, seu, Animalium infusoriorum, helminthicorum et testaceorum, non marinorum, succincta historia. Vol. v.1 (1773-1774). et Lipsiae: apud Heineck et Faber.

- ^ Paramoecium Hermann, 1783

- ^ Woodruff, Lorande Loss (September 1921). "The structure, life history, and intrageneric relationships of Paramecium calkinsi, sp. nov". The Biological Bulletin. 41 (3): 171–180. doi:10.2307/1536748. JSTOR 1536748.

- ^ Lynn, Denis (2008). The Ciliated Protozoa: Characterization, Classification, and Guide to the Literature (3 ed.). Springer Netherlands. ISBN 9781402082382.

- ^ Wichterman, R. (2012-12-06). The Biology of Paramecium. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781475703726.

- ^ a b Curds, Colin R.; Gates, Michael; Roberts, David McL. (1983). British and other freshwater ciliated protozoa. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 126.

- ^ Esteban, Genoveva F.; Fenchel, Tom; Finlay, Bland J. (2010). "Mixotrophy in Ciliates". Protist. 161 (5): 621–641. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2010.08.002. PMID 20970377.

- ^ Reece, Jane B. (2011). Campbell Biology. San Francisco: Pearson Education. p. 134. ISBN 9780321558237.

- ^ Blake, John R.; Sleigh, Michael A. (February 1974). "Mechanics of ciliary locomotion". Biological Reviews. 49 (1): 85–125. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.1974.tb01299.x. PMID 4206625. S2CID 41907168.

- ^ Ogura, A., and K. Takahashi. "Artificial deciliation causes loss of calcium-dependent responses in Paramecium" (1976): 170–172.

- ^ Katsu-Kimura, Yumiko; et al. (2009). "Substantial energy expenditure for locomotion in ciliates verified by means of simultaneous measurement of oxygen consumption rate and swimming speed". Journal of Experimental Biology. 212 (12): 1819–1824. Bibcode:2009JExpB.212.1819K. doi:10.1242/jeb.028894. PMID 19482999.

- ^ Osterman, Natan; Vilfan, Andrej (September 20, 2011). "Finding the ciliary beating pattern with optimal efficiency" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (38): 15727–15732. arXiv:1107.4273. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10815727O. doi:10.1073/pnas.1107889108. PMC 3179098. PMID 21896741.

- ^ Wichterman, R. (1986). The Biology of Paramecium. Springer US. pp. 200–1. ISBN 9781475703740.

- ^ Wichterman, Ralph (1985). The Biology of Paramecium. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-1-4757-0374-0.

- ^ Reece, Jane B.; et al. (2011). Campbell Biology. San Francisco: Pearson Education. p. 584. ISBN 9780321558237.

- ^ Mast, S. O. (February 1947). "The food-vacuole in Paramecium". The Biological Bulletin. 92 (1): 31–72. doi:10.2307/1537967. JSTOR 1537967. PMID 20284992.

- ^ Berger, Jacques (1980). "Feeding Behaviour of Didinium nasutum on Paramecium bursaria with Normal or Apochlorotic Zoochlorellae". Journal of General Microbiology. 118 (2): 397–404. doi:10.1099/00221287-118-2-397.

- ^ Kreutz, Martin; Stoeck, Thorsten; Foissner, Wilhelm (2012). "Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Paramecium (Viridoparamecium nov. subgen.) chlorelligerum Kahl (Ciliophora)". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 59 (6): 548–563. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00638.x. PMC 3866650. PMID 22827482.

- ^ a b c Preer, John R. Jr.; Preer, Louise B.; Jurand, Artur (June 1974). "Kappa and Other Endosymbionts in Paramecium aurelia". Bacteriological Reviews. 38 (2): 113–163. doi:10.1128/MMBR.38.2.113-163.1974. PMC 413848. PMID 4599970.

- ^ Aury, Jean-Marc; Jaillon, Oliver; Wincker, Patrick; et al. (November 2006). "Global trends of whole-genome duplications revealed by the ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia". Nature. 444 (7116): 171–8. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..171A. doi:10.1038/nature05230. PMID 17086204.

- ^ Lekomtsev, Sergey; Kolosov, Petr; Bidou, Laure; Frolova, Ludmila; Rousset, Jean-Pierre; Kisselev, Lev (June 26, 2007). "Different modes of stop codon restriction by the Stylonychia and Paramecium eRF1 translation termination factors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (26): 10824–9. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10410824L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703887104. PMC 1904165. PMID 17573528.

- ^ Armus, Harvard L.; Montgomery, Amber R.; Jellison, Jenny L. (Fall 2006). "Discrimination Learning in Paramecia (P. caudatum)". The Psychological Record. 56 (4): 489–498. doi:10.1007/BF03396029. S2CID 142785414.

- ^ Ginsburg, Simona; Jablonka, Eva (2009). "Epigenetic learning in non-neural organisms". Journal of Biosciences. 34 (4): 633–646. doi:10.1007/s12038-009-0081-8. PMID 19920348. S2CID 15507569.

- ^ a b c Prescott, D. M.; et al. (1971). "DNA of ciliated protozoa". Chromosoma. 34 (4): 355–366. doi:10.1007/bf00326311. S2CID 5013543.

- ^ Raikov, I.B (1972). "Nuclear phenomena during conjugation and autogamy in ciliates". Research in Protozoology. 4: 149.

- ^ Berger, James D. (October 1986). "Autogamy in Paramecium cell cycle stage-specific commitment to meiosis". Experimental Cell Research. 166 (2): 475–485. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(86)90492-1. PMID 3743667.

- ^ Raikov, I.B (1972). "Nuclear phenomena during conjugation and autogamy in ciliates". Research in Protozoology. 4: 151, 240.

- ^ Aufderheide, Karl J. (1986). "Clonal aging in Paramecium tetraurelia. II. Evidence of functional changes in the macronucleus with age". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 37 (3): 265–279. doi:10.1016/0047-6374(86)90044-8. PMID 3553762. S2CID 28320562.

- ^ Smith-Sonneborn, J. (1979). "DNA repair and longevity assurance in Paramecium tetraurelia". Science. 203 (4385): 1115–1117. Bibcode:1979Sci...203.1115S. doi:10.1126/science.424739. PMID 424739.

- ^ Holmes, George E.; Holmes, Norreen R. (July 1986). "Accumulation of DNA damages in aging Paramecium tetraurelia". Molecular and General Genetics. 204 (1): 108–114. doi:10.1007/bf00330196. PMID 3091993. S2CID 11992591.

- ^ Gilley, David; Blackburn, Elizabeth H. (1994). "Lack of telomere shortening during senescence in Paramecium" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (5): 1955–1958. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.1955G. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.5.1955. PMC 43283. PMID 8127914.

- ^ Bernstein, H; Bernstein, C (1991). Aging, Sex, and DNA Repair. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 153–156. ISBN 978-0120928606.

- ^ a b c Godau, Julia; Ferretti, Lorenza P.; Trenner, Anika; Dubois, Emeline; von Aesch, Christine; Marmignon, Antoine; Simon, Lauriane; Kapusta, Aurélie; Guérois, Raphaël; Bétermier, Mireille; Sartori, Alessandro A. (2019). "Identification of a miniature Sae2/Ctp1/CtIP ortholog from Paramecium tetraurelia required for sexual reproduction and DNA double-strand break repair" (PDF). DNA Repair. 77: 96–108. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.03.011. PMID 30928893. S2CID 89619084.

- ^ a b Thind AS, Vitali V, Guarracino MR, Catania F (May 2020). "What's Genetic Variation Got to Do with It? Starvation-Induced Self-Fertilization Enhances Survival in Paramecium". Genome Biol Evol. 12 (5): 626–638. doi:10.1093/gbe/evaa052. PMC 7239694. PMID 32163147.

- ^ Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RE (September 1985). "Genetic damage, mutation, and the evolution of sex". Science. 229 (4719): 1277–81. Bibcode:1985Sci...229.1277B. doi:10.1126/science.3898363. PMID 3898363.

External links

[edit] Media related to Paramecium at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paramecium at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Paramecium at Wikispecies

Data related to Paramecium at Wikispecies