Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shadow mask

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

The shadow mask is one of the two technologies used in the manufacture of cathode-ray tube (CRT) televisions and computer monitors which produce clear, focused color images. The other approach is the aperture grille, better known by its trade name, Trinitron. All early color televisions and the majority of CRT computer monitors used shadow mask technology. Both of these technologies are largely obsolete, having been increasingly replaced since the 1990s by the liquid-crystal display (LCD).

A shadow mask is a metal plate punched with tiny holes that separate the colored phosphors in the layer behind the front glass of the screen. Shadow masks are made by photochemical machining, a technique that allows for the drilling of small holes on metal sheets. Three electron guns at the back of the screen sweep across the mask, with the beams only reaching the screen if they pass through the holes. As the guns are physically separated at the back of the tube, their beams approach the mask from three slightly different angles, so after passing through the holes they hit slightly different locations on the screen.

The screen is patterned with dots of colored phosphor positioned so that each can only be hit by one of the beams coming from the three electron guns. For instance, the blue phosphor dots are hit by the beam from the "blue gun" after passing through a particular hole in the mask. The other two guns do the same for the red and green dots. This arrangement allows the three guns to address the individual dot colors on the screen, even though their beams are much too large and too poorly aimed to do so without the mask in place.

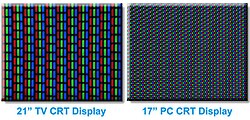

A red, a green, and a blue phosphor are generally arranged in a triangular shape (sometimes called a "triad"). For television use, modern displays (starting in the late 1960s) use rectangular slots instead of circular holes, improving brightness. This variation is sometimes referred to as a slot mask.

Development

[edit]Color television

[edit]Color television had been studied even before commercial broadcasting became common, but it was not until the late 1940s that the problem was seriously considered. At the time, a number of systems were being proposed that used separate red, green and blue signals (RGB), broadcast in succession. Most experimental systems broadcast entire frames in sequence, with a colored filter (or "gel") that rotated in front of an otherwise conventional black and white television tube. Each frame encoded one color of the picture, and the wheel spun in sync with the signal so the correct gel was in front of the screen when that colored frame was being displayed. Because they broadcast separate signals for the different colors, all of these systems were incompatible with existing black and white sets. Another problem was that the mechanical filter made them flicker unless very high refresh rates were used.[1] (This is conceptually similar to a DLP based projection display where a single DLP device is used for all three color channels.)

RCA worked along different lines entirely, using the luminance-chrominance system first introduced by Georges Valensi in 1938. This system did not directly encode or transmit the RGB signals; instead it combined these colors into one overall brightness figure, called the "luminance". This closely matched the black and white signal of existing broadcasts, allowing the picture to be displayed on black and white televisions. The remaining color information was separately encoded into the signal as a high-frequency modulation to produce a composite video signal. On a black and white television this extra information would be seen as a slight randomization of the image intensity, but the limited resolution of existing sets made this invisible in practice. On color sets the extra information would be detected, filtered out and added to the luminance to re-create the original RGB for display.[2]

Although RCA's system had enormous benefits, it had not been successfully developed because it was difficult to produce the display tubes. Black and white TVs used a continuous signal and the tube could be coated with an even painting of phosphor. With RCA's system, the color was changing continually along the line, which was far too fast for any sort of mechanical filter to follow. Instead, the phosphor had to be broken down into a discrete pattern of colored spots. Focusing the right signal on each of these tiny spots was beyond the capability of electron guns of the era.[2]

Numerous attempts

[edit]Through the 1940s and early 1950s a wide variety of efforts were made to address the color problem. A number of major companies continued to work with separate color "channels" with various ways to re-combine the image. RCA was included in this group; on 5 February 1940 they demonstrated a system using three conventional tubes combined to form a single image on a plate of glass, but the image was too dim to be useful.[2]

John Logie Baird, who made the first public color television broadcast using a semi-mechanical system on 4 February 1938, was already making progress on an all-electronic version. His design, the Telechrome, used two electron guns aimed at either side of a phosphor covered plate in the center of the tube. Development had not progressed far when Baird died in 1946.[3] A similar project was the Geer tube, which used a similar arrangement of guns aimed at the back of a single plate covered with small three-sided phosphor covered pyramids.[4]

However, all of these projects had problems with colors bleeding from one phosphor to another. In spite of their best efforts, the wide electron beams simply could not focus tightly enough to hit the individual dots, at least over the entirety of the screen. Moreover, most of these devices were unwieldy; the arrangement of the electron guns around the outside of the screen resulted in a very large display with considerable "dead space".

Rear-gun efforts

[edit]A more practical system would use a single gun at the back of the tube, firing at a single multi-color screen on the front. Through the early 1950s, several major electronics companies started development of such systems.

One contender was General Electric's Penetron, which used three layers of phosphor painted on top of each other on the back of the screen. Color was selected by changing the energy of the electrons in the beam so that they penetrated to different depths within the phosphor layers. Actually hitting the correct layer proved almost impossible, and GE eventually gave up on the technology for television use, although it went on to see some use in the avionics world where the color gamut could be reduced, often to three colors, which the system was able to achieve.[5]

More common were attempts to use a secondary focussing arrangement just behind the screen to produce the required accuracy. Paramount Pictures worked long and hard on the Chromatron, which used a set of wires behind the screen as a secondary "gun", further focusing the beam and steering it towards the correct color.[6] Philco's "Apple" tube used additional stripes of phosphor that released a burst of electrons when the electron beam swept across them, by timing the bursts it could adjust the passage of the beam and hit the correct colors.[7]

It would be years before any of these systems made their way into production. GE had given up on the Penetron by the early 1960s. Sony tried the Chromatron in the 1960s, but gave up and developed the Trinitron instead. The Apple tube re-emerged in the 1970s and had some success with a variety of vendors. But it was RCA's success with the shadow mask that dampened most of these efforts. Until 1968, every color television sold used the RCA shadow mask concept,[8] in the spring of that year Sony introduced their first Trinitron sets.[9]

Shadow mask

[edit]In 1938 German inventor Werner Flechsig first patented (received 1941, France) the seemingly simple concept of placing a sheet of metal just behind the front of the tube, and punching small holes in it. The holes would be used to focus the beam just before it hit the screen. Independently, Al Schroeder at RCA worked on a similar arrangement, but using three electron guns as well. When the lab leader explained the possibilities of the design to his superiors, he was promised unlimited manpower and funds to get it working.[10] Over a period of only a few months, several prototype color televisions using the system were produced.[11]

The guns, arranged in a delta pattern at the back of the tube, were aimed to focus on the metal plate and scanned it as normal. For much of the time during the scan, the beams would hit the back of the plate and be stopped. However, when the beams passed a hole they would continue to the phosphor in front of the plate. In this way, the plate ensured that the beams were perfectly aligned with the colored phosphor dots. This still left the problem of focusing on the correct colored dot. Normally the beams from the three guns would each be large enough to light up all three colored dots on the screen. The mask helped by mechanically attenuating the beam to a small size just before it hit the screen.[12]

But the real genius of the idea is that the beams approached the metal plate from different angles. After being cut off by the mask, the beams would continue forward at slightly different angles, hitting the screens at slightly different locations. The spread was a function of the distance between the guns at the back of the tube, and the distance between the mask plate and the screen. By painting the colored dots at the correct locations on the screen, and leaving some room between them to avoid interactions, the guns would be guaranteed to hit the right colored spot.[12]

Although the system was simple, it had a number of serious practical problems.

As the beam swept the mask, the vast majority of its energy was deposited on the mask, not the screen in front of it. A typical mask of the era might have only 15% of its surface open. To produce an image as bright as the one on a traditional B&W television, the electron guns in this hypothetical shadow mask system would have to be five times more powerful. Additionally, the dots on the screen were deliberately separated in order to avoid being hit by the wrong gun, so much of the screen was black.[13] This required even more power in order to light up the resulting image. And as the power was divided up among three of these much more powerful guns, the cost of implementation was much higher than for a similar B&W set.[14]

The amount of power deposited on the color screen was so great that thermal loading was a serious problem. The energy the shadow mask absorbs from the electron gun in normal operation causes it to heat up and expand, which leads to blurred or discolored images (see doming). Signals that alternated between light and dark caused cycling that further increased the difficulty of keeping the mask from warping.

Furthermore, the geometry required complex systems to keep the three beams properly positioned across the screen. If you consider the beam when it is sweeping across the middle area of the screen, the beams from the individual guns are each traveling the same distance and meet the holes in the mask at equal angles. In the corners of the screen some beams have to travel farther and all of them meet the hole at a different angle than at the middle of the screen. These issues required additional electronics and adjustments to maintain correct beam positioning.

Market introduction

[edit]During development, RCA was not sure that they could make the shadow mask system work. Although simple in concept, it was difficult to build in practice, especially at a reasonable price point. The company optioned several other technologies, including the Geer tube, in case the system didn't work out. When the first tubes were produced in 1950, these other lines were dropped.[citation needed]

Wartime advances in electronics had opened up large swaths of high frequency transmission to practical use, and in 1948 the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) started a series of meetings on the use of what would become the UHF channels. At the time there were very few television sets in use in the United States, so the stakeholder groups quickly settled on the idea of using UHF for a new, incompatible, color format. These meetings eventually selected a competing semi-mechanical field-sequential color system being promoted by CBS. However, in the midst of the meetings, RCA announced their efforts on compatible color, but too late to influence the proceedings. CBS color was introduced in 1950.[1][15]

However, the promise of the RCA system was so great that the National Television System Committee (NTSC) took up its cause. Between 1950 and 1953 they carried out a huge study on human color perception, and used that information to improve RCA's basic concept.[16] RCA had, by this time, produced experimental shadow mask sets that were an enormous leap in quality over any competitors. The system was dim, complex, large, power hungry and expensive for all these reasons, but provided a usable color image, and most importantly, was compatible with existing B&W signals. This had not been an issue in 1948 when the first FCC meetings were held, but by 1953 the number of B&W sets had exploded; there was no longer any way they could simply be abandoned.[citation needed]

When the NTSC proposed that their new standard be ratified by the FCC, CBS dropped its interest in its own system.[1] Everyone in the industry wanting to produce a set then licensed RCA's patents, and by the mid-1950s there were a number of sets commercially available. However, color sets were much more expensive than B&W sets of the same size, and required constant adjustment by field staff. By the early 1960s they still represented a small percentage of the television market in North America. The numbers exploded in the early 1960s, with 5,000 sets being produced a week in 1963.[8]

Manufacture

[edit]Shadow masks are made using a photochemical machining process. It starts out with a sheet of steel[17] or invar alloy[18] that is coated with photoresist, which is baked to solidify it, exposed to UV light through photomasks, developed to remove unexposed resist, the metal is etched using liquid acid, and then the photoresist is removed. One photomask has larger dark spots than the other, this creates tapered apertures.[19] The shadow mask is installed to the screen using metal pieces[20] or a rail or frame[21][22][23] that is fused to the funnel or the screen glass respectively,[24] holding the shadow mask in tension to minimize warping (if the mask is flat, used in flat screen CRT computer monitors) and allowing for higher image brightness and contrast. Bimetal springs may be used in CRTs used in TVs to compensate for warping that occurs as the electron beam heats the shadow mask, causing thermal expansion.[25]

Improvements, market acceptance

[edit]By the 1960s the first RCA patents were ending, while at the same time a number of technical improvements were being introduced. A number of these were worked into the GE Porta-Color set of 1966, which was an enormous success. By 1968 almost every company had a competing design, and color television moved from an expensive option to mainstream devices.

Doming problems due to thermal expansion of the shadow mask were solved in several ways. Some companies used a thermostat to measure the temperature and adjust the scanning to match the expansion.[26] Bi-metallic shadow masks, where differential expansion rates offset the issue, became common in the late 1960s. Invar and similar low-expansion alloys were introduced in the 1980s[27] These materials suffered from easy magnetization that can affect the colors, but this could be generally solved by including an automatic demagnetizing feature.[26] The last solution to be introduced was the "stretched mask", where the mask was welded to a frame, typically glass, at high temperatures. The frame was then welded to the inside of the tube. When the assembly cooled, the mask was under great tension, which no amount of heating from the guns would be able to remove.[28][29]

Improving brightness was another major line of work in the 1960s. The use of rare-earth phosphors produced brighter colors and allowed the strength of the electron beams to be reduced slightly. Better focusing systems, especially automatic systems that meant the set spent more time closer to perfect focus, allowed the dots to grow larger on the screen. The Porta-Color used both of these advances and re-arranged the guns to lie beside each other instead of in a triangle, allowing the dots to be extended vertically into slots that covered much more of the screen surface. This design, sometimes known as a "slot mask", became common in the 1970s.[26][30]

Another change that was widely introduced in the early 1970s was the use of a black material in the spaces around the inside of the phosphor pattern. This paint absorbed ambient light coming from the room, lowering the amount that was reflected back to the viewer. In order to make this work effectively, the phosphor dots were reduced in size, lowering their brightness. However, the improved contrast compared to ambient conditions allowed the faceplate to be made much more clear, allowing more light from the phosphor to reach the viewer and the actual brightness to increase.[26] Grey-tinted faceplates dimmed the image, but provided better contrast, because ambient light was attenuated before it reached the phosphors, and a second time as it returned to the viewer. Light from the phosphors was attenuated only once. This method changed over time, with TV tubes growing progressively more black over time.[citation needed]

In manufacturing color CRTs, the shadow masks or aperture grilles were also used to expose photoresist on the faceplate to ultraviolet light sources, accurately positioned to simulate arriving electrons for one color at a time. This photoresist, when developed, permitted phosphor for only one color to be applied where required. The process was used a total of three times, once for each color. (The shadow mask or aperture grille had to be removable and accurately re-positionable for this process to succeed.)

See also

[edit]- Dot pitch

- Aperture grille

- Cromaclear

- Porta-Color

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Ed Reitan, "CBS Field Sequential Color System" Archived 5 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, 24 August 1997.

- ^ a b c Ed Reitan, "RCA Dot Sequential Color System" Archived 7 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, 28 August 1997.

- ^ "The World's First High Definition Colour Television System" Archived 11 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Baird Television.

- ^ "Teacher's Tube", Time, 20 March 1950.

- ^ David Morton, "Electronics: The Life Story of a Technology" Archived 15 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007, p. 87.

- ^ U.S. Patent 2,692,532, "Cathode Ray Focusing Apparatus", Ernst O. Lawrence, University of California/Chromatic Television Laboratories (original Chromatron patent).

- ^ Richard Clapp et al., "A New Beam-Indexing Coor Television Display System", Proceedings of the IRE, September 1956, p. 1108–1114.

- ^ a b Gilmore, p. 80.

- ^ John Nathan, "Sony: The Private Life", Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Abramson & Sterling, p. 40.

- ^ Abramson & Sterling, p. 41.

- ^ a b Gilmore, p. 81.

- ^ Gilmore, p. 178.

- ^ Gilmore, p. 83.

- ^ Gilmore, p. 82.

- ^ "Colorimetry standards" Archived 24 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Broadcast Engineering.

- ^ "Anti-doming composition for a shadow-mask and processes for preparing the same". Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Shadow mask". Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Manufacture of Color Picture Tubes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Shadow mask mounting arrangement for color CRT". Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Flat tension mask type cathode ray tube". Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Cathode ray tube with bracket for mounting a shadow mask frame". Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Color cathode ray tube with improved shadow mask mounting system". Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Innovative use of magnetic quadrupoles in cathode-ray tubes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2020.

- ^ Corporation, Bonnier (5 August 1986). "Popular Science". Bonnier Corporation. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Len Buckwalter, "1970 Television: The Picture Is Brighter Than Ever" Archived 4 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, "Popular Science", October 1969, p. 142–145, 224.

- ^ "Taking the heat out of flat-screen television..." Archived 4 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, New Scientist, 3 October 1985, p. 35.

- ^ James Foley, "Computer graphics: principles and practice" Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Addison-Wesley, 1996, p. 160.

- ^ Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. 1986. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Jerry Whitaker, "DTV handbook" Archived 4 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, McGraw-Hill, 2001, p. 461–462.

Bibliography

[edit]- Albert Abramson and Christopher Sterling, "The History of Television, 1942 to 2000" Archived 4 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- C. P. Gilmore, "Color TV: Is It Finally Worth the Money?" Archived 4 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Popular Science, August 1963, pp. 80–83, 178.