Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A mask is an object normally worn on the face, typically for protection, disguise, performance, or entertainment, and often employed for rituals and rites. Masks have been used since antiquity for both ceremonial and practical purposes, as well as in the performing arts and for entertainment. They are usually worn on the face, although they may also be positioned for effect elsewhere on the wearer's body.

In art history, especially sculpture, "mask" is the term for a face without a body that is not modelled in the round (which would make it a "head"), but for example appears in low relief.

Etymology

[edit]

The word "mask" appeared in English in the 1530s, from Middle French masque "covering to hide or guard the face", derived in turn from Italian maschera, from Medieval Latin masca "mask, specter, nightmare".[1] This word is of uncertain origin, perhaps from Arabic maskharah مَسْخَرَۃٌ "buffoon", from the verb sakhira "to ridicule". However, it may also come from Provençal mascarar "to black (the face)" (or the related Catalan mascarar, Old French mascurer). This in turn is of uncertain origin – perhaps from a Germanic source akin to English "mesh", but perhaps from mask- "black", a borrowing from a pre-Indo-European language.[2] One German author claims the word "mask" is originally derived from the Spanish más que la cara (literally, "more than the face" or "added face"), which evolved to "máscara", while the Arabic "maskharat" – referring to the buffoonery which is possible only by disguising the face – would be based on these Spanish roots.[3] Other related forms are Hebrew masecha= "mask"; Arabic maskhara مَسْخَرَ = "he ridiculed, he mocked", masakha مَسَخَ = "he transfomed" (transitive).

History

[edit]

The use of masks in rituals or ceremonies is a very ancient human practice across the world,[4] although masks can also be worn for protection, in hunting, in sports, in feasts, or in wars – or simply used as ornamentation.[5] Some ceremonial or decorative masks were not designed to be worn. Although the religious use of masks has waned, masks are used sometimes in drama therapy or psychotherapy.[6]

One of the challenges in anthropology is finding the precise derivation of human culture and early activities, the invention and use of the mask is only one area of unsolved inquiry. The use of masks dates back several millennia. It is conjectured that the first masks may have been used by primitive people to associate the wearer with some kind of unimpeachable authority, such as a deity, or to otherwise lend credence to the person's claim on a given social role.

The earliest known anthropomorphic artwork is circa 30,000–40,000 years old.[note 1] The use of masks is demonstrated graphically at some of these sites. Insofar as masks involved the use of war-paint, leather, vegetative material, or wooden material, such masks failed to be preserved, however, they are visible in Paleolithic cave drawings, of which dozens have been preserved.[note 2] At the Neanderthal Roche-Cotard site in France, a flintstone likeness of a face was found that is approximately 35,000 years old, but it is not clear whether it was intended as a mask.[7][8]

In the Greek bacchanalia and the Dionysus cult, which involved the use of masks, the ordinary controls on behaviour were temporarily suspended, and people cavorted in merry revelry outside their ordinary rank or status. René Guénon claims that in the Roman saturnalia festivals, the ordinary roles were often inverted. Sometimes a slave or a criminal was temporarily granted the insignia and status of royalty, only to be killed after the festival ended.[9] The Carnival of Venice, in which all are equal behind their masks, dates back to 1268 AD.[10] The use of carnivalesque masks in the Jewish Purim festivities probably originated in the late 15th century, although some Jewish authors claim it has always been part of Judaic tradition.[11]

The North American Iroquois tribes used masks for healing purposes (see False Face Society). In the Himalayas, masks functioned above all as mediators of supernatural forces.[12][13][14] Yup'ik masks could be small 3-inch (7.6 cm) finger masks, but also 10-kilogram (22 lb) masks hung from the ceiling or carried by several people.[15][16] Masks have been created with plastic surgery for mutilated soldiers.[17]

Masks in various forms – sacred, practical, or playful – have played a crucial historical role in the development of understandings about "what it means to be human", because they permit the imaginative experience of "what it is like" to be transformed into a different identity (or to affirm an existing social or spiritual identity).[18] Not all cultures have known the use of masks, but most of them have.[19][20][note 3]

Masks in performance

[edit]

Throughout the world, masks are used for their expressive power as a feature of masked performance – both ritually and in various theatre traditions. The ritual and theatrical definitions of mask use frequently overlap and merge but still provide a useful basis for categorisation. The image of juxtaposed comedy and tragedy masks are widely used to represent the performing arts, and specifically drama.

In many dramatic traditions including the theatre of ancient Greece, the classical noh drama of Japan (14th century to present), the traditional lhamo drama of Tibet, talchum in Korea, and the topeng dance of Indonesia, masks were or are typically worn by all the performers, with several different types of mask used for different types of character.

In Ancient Rome, the word persona meant 'a mask'; it also referred to an individual who had full Roman citizenship. A citizen could demonstrate his or her lineage through imagines – death masks of ancestors. These were wax casts kept in a lararium (the family shrine). Rites of passage, such as initiation of young members of the family or funerals, were carried out at the shrine under the watch of the ancestral masks. At funerals, professional actors would wear these masks to perform deeds of the lives of the ancestors,[21] thus linking the role of mask as a ritual object and in theatre.

Masks are a familiar and vivid element in many folk and traditional pageants, ceremonies, rituals, and festivals, and are often of an ancient origin. The mask is normally a part of a costume that adorns the whole body and embodies a tradition important to the religious and/or social life of the community as whole or a particular group within the community. Masks are used almost universally and maintain their power and mystery both for their wearers and their audience. The continued popularity of wearing masks at carnival, and for children at parties and for festivals such as Halloween are good examples. Nowadays these are usually mass-produced plastic masks, often associated with popular films, television programmes, or cartoon characters – they are, however, reminders of the enduring power of pretense and play and the power and appeal of masks.

Ritual masks

[edit]Ritual masks occur throughout the world, and although they tend to share many characteristics, highly distinctive forms have developed. The function of the masks may be magical or religious; they may appear in rites of passage or as a make-up for a form of theatre. Equally masks may disguise a penitent or preside over important ceremonies; they may help mediate with spirits, or offer a protective role to the members of a society who use their powers.[22] Biologist Jeremy Griffith has suggested that ritual masks, as representations of the human face, are extremely revealing of the two fundamental aspects of the human psychological condition: firstly, the repression of a cooperative, instinctive self or soul; and secondly, the extremely angry state of the unjustly condemned conscious thinking egocentric intellect.[23]

In parts of Australia, giant totem masks cover the body.

Africa

[edit]

There are a wide variety of masks used in Africa. In West Africa, masks are used in masquerades that form part of religious ceremonies enacted to communicate with spirits and ancestors. Examples are the masquerades of the Yoruba, Igbo, and Edo cultures, including Egungun Masquerades and Northern Edo Masquerades. The masks are usually carved with an extraordinary skill and variety by artists who will usually have received their training as an apprentice to a master carver – frequently it is a tradition that has been passed down within a family through many generations. Such an artist holds a respected position in tribal society because of the work that he or she creates, embodying not only complex craft techniques but also spiritual/social and symbolic knowledge.[24] African masks are also used in the Mas or Masquerade of the Caribbean Carnival.

Djolé (also known as Jolé or Yolé) is a mask-dance from Temine people in Sierra Leone. Males wear the mask, although it does depict a female.

Many African masks represent animals. Some African tribes believe that the animal masks can help them communicate with the spirits who live in forests or open savannas. People of Burkina Faso known as the Bwa and Nuna call to the spirit to stop destruction. The Dogon of Mali have complex religions that also have animal masks. Their three main cults use seventy-eight different types of masks. Most of the ceremonies of the Dogon culture are secret, although the antelope dance is shown to non-Dogons. The antelope masks are rough rectangular boxes with several horns coming out of the top. The Dogons are expert agriculturists and the antelope symbolizes a hard-working farmer.[25]

Another culture that has a very rich agricultural tradition is the Bamana people of Mali. The antelope (called Chiwara) is believed to have taught man the secrets of agriculture. Although the Dogons and Bamana people both believe the antelope symbolises agriculture, they interpret elements the masks differently. To the Bamana people, swords represent the sprouting of grain.

Masks may also indicate a culture's ideal of feminine beauty. The masks of Punu of Gabon have highly arched eyebrows, almost almond-shaped eyes and a narrow chin. The raised strip running from both sides of the nose to the ears represent jewellery. Dark black hairstyle, tops the mask off. The whiteness of the face represents the whiteness and beauty of the spirit world. Only men wear the masks and perform the dances with high stilts despite the fact that the masks represent women. One of the most beautiful representations of female beauty is the Idia's Mask of Benin in present-day Edo State of Nigeria. It is believed to have been commissioned by a king of Benin in memory of his mother. To honor his dead mother, the king wore the mask on his hip during special ceremonies.[26]

The Senoufo people of the Ivory Coast represent tranquility by making masks with eyes half-shut and lines drawn near the mouth. The Temne of Sierra Leone use masks with small eyes and mouths to represent humility and humbleness. They represent wisdom by making bulging forehead. Other masks that have exaggerated long faces and broad foreheads symbolize the soberness of one's duty that comes with power. War masks are also popular. The Grebo of the Ivory Coast and Liberia carve masks with round eyes to represent alertness and anger, with the straight nose to represent unwillingness to retreat.[27]

Today, the qualities of African art are beginning to be more understood and appreciated. However, most African masks are now being produced for the tourist trade. Although they often show skilled craftsmanship, they nearly always lack the spiritual character of the traditional tribal masks.

Oceania

[edit]The variety and beauty of the masks of Melanesia are almost as highly developed as in Africa. It is a culture where ancestor worship is dominant and religious ceremonies are devoted to ancestors. Inevitably, many of the mask types relate to use in these ceremonies and are linked with the activities of secret societies. The mask is regarded as an instrument of revelation, giving form to the sacred. This is often accomplished by linking the mask to an ancestral presence, and thus bringing the past into the present.

As a culture of scattered islands and peninsulars, Melanesian mask forms have developed in a highly diversified fashion, with a great deal of variety in their construction and aesthetic.[28] In Papua New Guinea, six-metre-high totem masks are placed to protect the living from spirits; whereas the duk-duk and tubuan masks of New Guinea are used to enforce social codes by intimidation. They are conical masks, made from cane and leaves.[29]

North America

[edit]

North American indigenous cultures in the Arctic and para-Arctic regions have tended towards simple religious practice but a highly evolved and rich mythology, especially concerning hunting. In some areas, annual shamanic ceremonies involved masked dances and these strongly abstracted masks are arguably the most striking artifacts produced in this region. Inuit groups vary widely and share neither a common mythology nor language. Not surprisingly their mask traditions are also often different, although their masks are often made out of driftwood, animal skins, bones, and feathers. In some areas Inuit women use finger masks during storytelling and dancing.[30]

Indigenous Pacific Northwest coastal cultural groups generally included highly skilled woodworkers. Their masks were often masterpieces of carving, sometimes with movable jaws, with the parts sometimes moved by pulling cords, or a mask within a mask to represent a magical transformation. The carving of masks was an important feature of woodcraft, along with many other features that often combined the utilitarian with the symbolic, such as shields, canoes, poles, and houses.

Woodland tribes, especially in the northeastern and around the Great Lakes, cross-fertilized culturally with one another. The Iroquois made spectacular wooden 'false face' masks, used in healing ceremonies and carved from living trees. These masks appear in a great variety of shapes, depending on their precise function.

Pueblo craftsmen produced impressive work for masked religious ritual, especially the Hopi and Zuni. The kachinas (gods and spirits) frequently take the form of highly distinctive and elaborate masks that are used in ritual dances. These are usually made of leather with appendages of fur, feathers, or leaves. Some cover the face, some the whole head, and are often highly abstracted forms. Navajo masks appear to be inspired by the Pueblo prototypes.[31][32]

In modern immigrant Euro-American culture, masking is a common feature of Mardi Gras traditions, most notably in New Orleans. Costumes and masks (originally inspired by masquerade balls) are frequently worn by "krewe"-members on Mardi Gras Day; local laws against using a mask to conceal one's identity are suspended for the day.

Latin America

[edit]

Distinctive styles of masks began to emerge in pre-Hispanic America about 1200 BC, although there is evidence of far older mask forms. In the Andes, masks were used to dress the faces of the dead. These were originally made of fabric, but later burial masks were sometimes made of beaten copper or gold, and occasionally of clay.

For the Aztecs, human skulls were prized as war trophies, and skull masks were not uncommon. Masks were also used as part of court entertainments, possibly combining political with religious significance.

In post-colonial Latin America, pre-Columbian traditions merged with Christian rituals, and syncretic masquerades and ceremonies, such as All Souls/Day of the Dead developed, despite efforts of the Church to stamp out the indigenous traditions. Masks remain an important feature of popular carnivals and religious dances, such as The Dance of the Moors and Christians. Mexico, in particular, retains a great deal of creativity in the production of masks, encouraged by collectors. Wrestling matches, where it is common for the participants to wear masks, are very popular, and many of the wrestlers can be considered folk heroes. For instance, the popular wrestler El Santo continued wearing his mask after retirement, revealed his face briefly only in old age, and was buried wearing his silver mask.[33][34]

Asia

[edit]China

[edit]

In China, masks are thought to have originated in ancient religious ceremonies. Images of people wearing masks have been found in rock paintings along the Yangtze. Later mask forms brings together myths and symbols from shamanism and Buddhism.[35]

Shigong dance masks were used in shamanic rituals to thank the gods, while nuo dance masks protected from bad spirits. Wedding masks were used to pray for good luck and a lasting marriage, and "Swallowing Animal" masks were associated with protecting the home and symbolised the "swallowing" of disaster. Opera masks were used in a basic "common" form of opera performed without a stage or backdrops. These led to colourful facial patterns that we see in today's Peking opera.

India/Sri Lanka/Indo-China

[edit]Masked characters, usually divinities, are a central feature of Indian dramatic forms, many based on depicting the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana. Countries that have had strong Indian cultural influences – Cambodia, Burma, Indonesia, Thailand, and Lao – have developed the Indian forms, combined with local myths, and developed their own characteristic styles.

The masks are usually highly exaggerated and formalised, and share an aesthetic with the carved images of monstrous heads that dominate the facades of Hindu and Buddhist temples. These faces or Kirtimukhas, 'Visages of Glory', are intended to ward off evil and are associated with the animal world as well as the divine. During ceremonies, these visages are given active form in the great mask dramas of the South and South-eastern Asian region.[35]

Indonesia

[edit]In Indonesia, the mask dance predates Hindu-Buddhist influences. It is believed that the use of masks is related to the cult of the ancestors, which considered dancers the interpreters of the gods. Native Indonesian tribes such as Dayak have masked Hudoq dance that represents nature spirits. In Java and Bali, masked dance is commonly called topeng and demonstrated Hindu influences as it often feature epics such as Ramayana and Mahabharata. The native story of Panji also popular in topeng masked dance. Indonesian topeng dance styles are widely distributed, such as topeng Bali, Cirebon, Betawi, Malang, Yogyakarta, and Solo.

Japan

[edit]

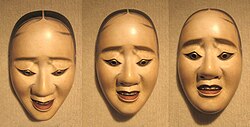

Japanese masks are part of a very old and highly sophisticated and stylized theatrical tradition. Although the roots are in prehistoric myths and cults, they have developed into refined art forms. The oldest masks are the gigaku. The form no longer exists, and was probably a type of dance presentation. The bugaku developed from this – a complex dance-drama that used masks with moveable jaws.

The nō or noh mask evolved from the gigaku and bugaku and are acted entirely by men. The masks are worn throughout very long performances and are consequently very light. The nō mask is the supreme achievement of Japanese mask-making. Nō masks represent gods, men, women, madmen and devils, and each category has many sub-divisions. Kyōgen are short farces with their own masks, and accompany the tragic nō plays. Kabuki is the theatre of modern Japan, rooted in the older forms, but in this form masks are replaced by painted faces.[36]

Korea

[edit]

Korean masks have a long tradition associated with shamanism and later in ritual dance. Korean masks were used in war, on both soldiers and their horses; ceremonially, for burial rites in jade and bronze and for shamanistic ceremonies to drive away evil spirits; to remember the faces of great historical figures in death masks; and in the arts, particularly in ritual dances, courtly, and theatrical plays. The present uses are as miniature masks for tourist souvenirs, or on mobile phones, where they hang as good-luck talismans.

Middle East

[edit]

Theatre in the Middle East, as elsewhere, was initially of a ritual nature, dramatising human relationships with nature, the deities, and other human beings. It grew out of sacred rites of myths and legends performed by priests and lay actors at fixed times and often in fixed locations. Folk theatre – mime, mask, puppetry, farce, juggling – had a ritual context in that it was performed at religious or rites of passage such as days of naming, circumcisions, and marriages. Over time, some of these contextual ritual enactments became divorced from their religious meaning and they were performed throughout the year. Some 2500 years ago, kings and commoners alike were entertained by dance and mime accompanied by music where the dancers often wore masks, a vestige of an earlier era when such dances were enacted as religious rites. According to George Goyan, this practice evoked that of Roman funeral rites where masked actor-dancers represented the deceased with motions and gestures mimicking those of the deceased while singing the praise of their lives (see Masks in Performance above).[37]

Europe

[edit]

The oldest representations of masks in Europe are animal masks, such as the cave paintings of Lascaux in the Dordogne in southern France. Such masks survive in the alpine regions of Austria and Switzerland, and may be connected with hunting or shamanism. Masks are used throughout Europe in modern times, and are frequently integrated into regional folk celebrations and customs. Old masks are preserved and can be seen in museums and other collections, and much research has been undertaken into the historical origins of masks. Most probably represent nature spirits, and as a result many of the associated customs are seasonal. The original significance would have survived only until the introduction of Christianity, which incorporated many of the customs into its own traditions. In that process their meanings were changed also so, for example, old gods and goddesses originally associated with the celebrations were demonised and viewed as mere devils, or were subjugated to the Abrahamic God.

Many of the masks and characters used in European festivals belong to the contrasting categories of the 'good', or 'idealised beauty', set against the 'ugly' or 'beastly' and grotesque. This is particularly true of the Germanic and Central European festivals. Another common type is the Fool, sometimes considered to be the synthesis of the two contrasting types, Handsome and Ugly.[39] Masks also tend to be associated with New Year and Carnival festivals.

The debate about the meaning of these and other mask forms continues in Europe, where monsters, bears, wild men, harlequins, hobby horses, and other fanciful characters appear in carnivals throughout the continent. It is generally accepted that the masks, noise, colour, and clamour are meant to drive away the forces of darkness and winter, and open the way for the spirits of light and the coming of spring.[40] In Sardinia existed the tradition of Mamuthones e Issohadores of Mamoiada; Boes e Merdules of Ottana; Thurpos of Orotelli; S'Urtzu, Su 'Omadore and Sos Mamutzones of Samugheo. The celebration of Giubiana in Canzo (Lombardy) preserves a tradition of masks of anguane, wild man, bear and its hunter, and Giubiana herself, among others.

Another tradition of European masks developed, more self-consciously, from court and civic events, or entertainments managed by guilds and co-fraternities. These grew out of the earlier revels and had become evident by the 15th century in places such as Rome and Venice, where they developed as entertainments to enliven towns and cities. Thus the Maundy Thursday carnival in St. Marks Square in Venice, attended by the Doge and aristocracy, also involved the guilds, including a guild of maskmakers.[41] There is evidence of 'commedia dell'arte'-inspired Venetian masks and by the late 16th century the Venetian Carnival began to reach its peak and eventually lasted a whole 'season' from January until Lent. By the 18th century, it was already a tourist attraction, Goethe saying that he was ugly enough not to need a mask. The carnival was repressed during the Napoleonic Republic, although in the 1980s its costumes and the masks aping the 18th century heyday were revived.[42][failed verification] It appears other cities in central Europe were influenced by the Venetian model.

During the Reformation, many of these carnival customs began to die out in Protestant regions, although they seem to have survived in Catholic areas despite the opposition of the ecclesiastical authorities. So by the 19th century, the carnivals of the relatively wealthy bourgeois town communities, with elaborate masques and costumes, existed side by side with the ragged and essentially folkloric customs of the rural areas.[22] Although these civic masquerades and their masks may have retained elements drawn from popular culture, the survival of carnival in the 19th century was often a consequence of a self-conscious 'folklore' movement that accompanied the rise of nationalism in many European countries.[39] Nowadays, during carnival in the Netherlands masks are often replaced with face paint for more comfort.

In the beginning of the new century, on 19 August 2004, the Bulgarian archaeologist Georgi Kitov discovered a 673 g gold mask in the burial mound "Svetitsata" near Shipka, Central Bulgaria. It is a very fine piece of workmanship made out of massive 23 karat gold. Unlike other masks discovered in the Balkans (of which three are in Republic of Macedonia and two in Greece), it is now kept in the National Archaeological Museum in Sofia. It is considered to be the mask of a Thracian king, presumably Teres.

Masks in theatre

[edit]Masks play a key part within world theatre traditions. They continue to be a vital force within contemporary theatre, and their usage takes a variety of forms and has often developed from, or continues to be part of old, highly sophisticated, stylized theatrical traditions.

In many cultural traditions, the masked performer is a central concept and is highly valued. In the western tradition, actors in Ancient Greek theatre wore masks, as they do in traditional Japanese Noh drama. In some Greek masks, the wide and open mouth of the mask contained a brass megaphone enabling the voice of the wearer to be projected into the large auditoria. In medieval Europe, masks were used in mystery and miracle plays to portray allegorical creatures, and the performer representing God frequently wore a gold or gilt mask. During the Renaissance, masques and ballet de cour developed – courtly masked entertainments that continued as part of ballet conventions until the late eighteenth century. The masked characters of the Commedia dell'arte included the ancestors of the modern clown. In contemporary western theatre, the mask is often used alongside puppetry to create a theatre that is essentially visual, rather than verbal, and many of its practitioners have been visual artists.

Contemporary theatre

[edit]

Masks and puppets were often incorporated into the theatre work of European avant-garde artists from the turn of the nineteenth century. Alfred Jarry, Pablo Picasso, Oskar Schlemmer, other artists of the Bauhaus School, as well as surrealists and Dadaists, experimented with theatre forms and masks in their work.

In the 20th century, many theatre practitioners, such as Meyerhold, Edward Gordon Craig, Jacques Copeau, and others in their lineage, attempted to move away from Naturalism. They turned to sources such as Oriental Theatre (particularly Japanese Noh theatre) and commedia dell'arte,[43] both of which forms feature masks prominently.

Edward Gordon Craig (1872–1966) in A Note on Masks (1910) proposed the virtues of using masks over the naturalism of the actor.[44] Craig was highly influential, and his ideas were taken up by Brecht, Cocteau, Genet, Eugene O'Neill – and later by Arden, Grotowski, Brook, and others who "attempted to restore a ritualistic if not actually religious significance to theatre".[45]

Copeau, in his attempts to "Naturalise" actors,[46] decided to use masks to liberate them from their "excessive awkwardness". In turn, Copeau's work with masks was taken on by his students including Etienne Decroux and later, via Jean Daste and Jacques Lecoq.[43] Lecoq, having worked as movement director at Teatro Piccalo in Italy, was influenced by the Commedia tradition. Lecoq met Amleto Satori, a sculptor, and they collaborated on reviving the techniques of making traditional leather Commedia masks. Later, developing Copeau's "noble mask", Lecoq would ask Satori to make him masques neutre (the neutral mask). For Lecoq, masks became an important training tool, the neutral mask being designed to facilitate a state of openness in the student-performers, moving gradually on to character and expressive masks, and finally to "the smallest mask in the world" the clown's red-nose. One highly important feature of Lecoq's use of mask, wasn't so much its visual impact on stage, but how it changed the performers movement on stage. It was a body-based approach to mask work, rather than a visually led one.[43][47] Lecoq's pedagogy has been hugely influential for theatre practitioners in Europe working with mask and has been exported widely across the world. This work with masks also relates to performing with portable structures and puppetry. Students of Lecoq have continued using masks in their work after leaving the school, such as in John Wright's Trestle Theatre.

In America, mask-work was slower to arrive, but the Guerrilla Theatre movement, typified by groups such as the San Francisco Mime Troupe and Bread and Puppet Theatre took advantage of it. Influenced by modern dance, modern mime, Commedia dell'arte and Brecht such groups took to the streets to perform highly political theatre. Peter Schumann, the founder of Bread and Puppet theatre, made particular use of German Carnival masks.[48] Bread and Puppet inspired other practitioners around the world, many of whom used masks in their work. In the US and Canada, these companies include In the Heart of the Beast Puppet and Mask Theater of Minneapolis; Arm-of-the Sea Theatre from New York State; Snake Theater from California; and Shadowland Theatre of Toronto, Ontario. These companies, and others, have a strong social agenda, and combine masks, music and puppetry to create a visual theatrical form. Another route masks took into American Theatre was via dancer/choreographers such as Mary Wigman, who had been using masks in dance and had emigrated to America to flee the Nazi regime.

In Europe, Schumann's influence combined with the early avant-garde artists to encourage groups such as Moving Picture Mime Show and Welfare State (both in the UK). These companies had a big influence on the next generation of groups working in visual theatre, including IOU and Horse and Bamboo Theatre, who create a theatre in which masks are used along with puppets, film and other visual forms, with an emphasis on the narrative structure.[49]

Functional masks

[edit]Masks are also familiar as pieces of kit associated with practical functions, usually protective, including in sports and during plagues:

Medical

[edit]

Some masks are used for medical purposes:

- N95 respirator, used for the prevention of tuberculosis and other pathogens

- FFP2, European equivalent

- Oxygen mask, a piece of medical equipment that assists breathing.

- Anesthetic mask.

- Burn mask, a piece of medical equipment that protects the burn tissue from contact with other surfaces, and minimises the risk of infection.

- Surgical mask, a tool for respiratory source control.

- Face shield, to protect a medical professional from bodily fluids.

- Pocket mask or CPR mask, used to safely deliver rescue breaths during a cardiac arrest or respiratory arrest.

- Cloth face mask, an alternative to respirators and surgical masks during shortages.

Protective

[edit]

Protective masks are pieces of kit or equipment worn on the head and face to afford protection to the wearer, and today usually have these functions:

- Providing a supply of air or filtering the outside air (respirators and dust masks).

- Protecting the face against flying objects or dangerous environments, while allowing vision.

In Roman gladiatorial tournaments masks were sometimes used. From archaeological evidence it is clear that these were not only protective but also helped make the wearer appear more intimidating. In medieval Europe and in Japan soldiers and samurai wore similarly ferocious-looking protective armour, extending to face-masks.

In the 16th century, the Visard was worn by women to protect from sunburn. Today this function is attributed to thin balaclavas.

In sport the protective mask will often have a secondary function to make the wearer appear more impressive as a competitor.

Before strong transparent materials such as polycarbonate were invented, visors to protect the face had to be opaque with small eyeslits, and were a sort of mask, as often in mediaeval suits of armour, and (for example) Old Norse grímr meant "mask or visor".

Disguise

[edit]

Masks are sometimes used to avoid recognition. As a disguise the mask acts as a form of protection for the wearer who wishes to assume a role or task without being identified by others.

- Robbers and other criminal perpetrators may wear masks as a means in concealing their faces and thus identities from their victims and from law enforcement.

- Occasionally a witness for the prosecution appears in court in a mask to avoid being recognized by associates of the accused.

- Participants in a black bloc at protests usually wear masks, often bandannas, to avoid recognition, and to try to protect against any riot control agents used.

- In fiction, superheroes and supervillains often wear masks or cowls for protection and to brand themselves.[50]

Masks are also used to prevent recognition while showing membership of a group:

- Masks are use by penitents in ceremonies to disguise their identity in order to make the act of penitence more selfless. The Semana Santa parades throughout Spain and in Hispanic or Catholic countries throughout the world are examples of this, with their cone-shaped masks known as capirote.

- Masks are used by vigilante groups.

- The cone-shaped mask in particular is identified with the Ku Klux Klan in a self-conscious effort to combine the hiding of personal identity with the promotion of a powerful and intimidating image.

- Members of the group Anonymous frequently wear masks (usually Guy Fawkes masks, best known from V for Vendetta) when they attend protests.

While the niqāb usually shows membership of some Islamic community, its purpose is not to hinder recognition, although it falls under some anti-mask laws such as the French ban on face covering.

Occupational

[edit]- Beaked masks containing herbs in the beak were worn in early modern Europe by plague doctors[51][better source needed] to try to ward off the Black Death.

- Filter mask, a piece of safety equipment.

- Full-face diving mask as part of self-contained breathing apparatus for divers and others; some let the wearer talk to others through a built-in communication device

- Respirator (gas or particulate mask), a mask worn on the face to protect the body from airborne pollutants and toxic materials, and fine particulate matter or infectious particles.

- Oxygen mask worn by high-altitude pilots, or used in medicine to deliver oxygen, anesthetic, or other gases to patients

- Welding mask to protect the welder's face and eyes from the brightness and sparks created during welding

Sports

[edit]

- American football helmet face mask

- Balaclava, also known as a "ski mask", to protect the face against cold air.

- Baseball catcher's mask.

- Diving mask, an item of diving equipment that allows scuba divers, free-divers, and snorkelers to see clearly underwater.

- Fencing mask.

- Goaltender mask, a mask worn by an ice or field hockey goaltender to protect the head and face from injury.

- Hurling helmets were made mandatory in 2010, and have a wire mask on the front to protect the player's face.

- Kendo, a mask called Men is used in this Japanese sword-fighting martial art.

- Paintball mask.

- Visor (ice hockey).

An interesting example of a sports mask that confounds the protective function is the wrestling mask, a mask most widely used in the Mexican/Latin lucha libre style of wrestling. In modern lucha libre, masks are colourfully designed to evoke the images of animals, gods, ancient heroes, and other archetypes. The mask is considered "sacred" to some degree, placing its role closer to the ritual and performance function.[52]

Punitive

[edit]

Masks are sometimes used to punish the wearer either by signalling their humiliation or causing direct suffering:

- Particularly uncomfortable types, such as an iron mask, for example the Scold's bridle, are fit as devices for humiliation, corporal punishment or torture.

- Masks were used to alienate and silence prisoners in Australian jails in the late 19th century. They were made of white cloth and covered the face, leaving only the eyes visible.

- Use of masks is also common in BDSM practices.

Fashion

[edit]Decorative masks may be worn as part of a costume outside of ritual or ceremonial functions. This is often described as a masque, and relates closely to carnival styles. For example, attendants of a costume party will sometimes wear masks as part of their costumes.

Several artists in the 20th and 21st century, such as Isamaya Ffrench and Damselfrau, create masks as wearable art.[53]

- Wrestling masks are used most widely in Mexican and Japanese wrestling. A wrestler's mask is usually related to a wrestler's persona (for example, a wrestler known as 'The Panda' might wear a mask with a panda's facial markings). Often, wrestlers will put their masks on the line against other wrestlers' masks, titles or an opponent's hair. While in Mexico and Japan, masks are a sign of tradition, they are looked down upon in the United States and Canada.

- Several bands and performers, notably members of the groups Slipknot, Mental Creepers and Gwar, and the guitarist Buckethead, wear masks when they perform on stage. Several other groups, including Kiss, Alice Cooper, and Dimmu Borgir simulate the effect with facepaint. Hollywood Undead also wears masks but often remove them mid-performance.

- Leather-working, steampunk, and other methods and themes are occasionally used to create artisanal gas masks.

One user of masks in fashion is musician and fashion designer Kanye West.[54] West has donned masks from Balenciaga and Maison Margiela, most notably on his Yeezus Tour.

In works of fiction

[edit]Masks have been used in many horror films to conceal the identities of the killer. Notable examples include Jason Voorhees of the Friday the 13th series, Jigsaw Killer from Saw, Ghostface of the Scream series, and Michael Myers of the Halloween series.

Drama

[edit]- Bridal Mask - 2012 South Korean television series

Other types

[edit]- A "buccal mask" is a mask that covers only the cheeks (hence the adjective "buccal") and mouth.

- A death mask is a mask either cast from or applied to the face of a recently deceased person.

- A "facial" (short for facial mask) is a temporary mask, not solid, used in cosmetics or as therapy for skin treatment.

- A "life mask" is a plaster cast of a face, used as a model for making a painting or sculpture.

- An animal roleplay mask is used for people to create a more animal-like image in fetish role play.

- A variety of technologies attempt to fool facial recognition software by the use of anti-facial recognition masks.[55]

Gallery

[edit]-

Kwakwaka'wakw, Baleen Whale Mask, 19th century, Brooklyn Museum

-

A Cherokee ceremonial mask made of wood

-

Various Balinese topeng dance masks

-

Fools Meeting or Parade, Meßkirch, Germany

-

Dance Mask (Takü), 20th century, Brooklyn Museum. These full-body masks are worn for the mourning, or ónyo ("weeping") ceremony, a multi-day ritual held approximately a year after an individual's death.

-

Life mask of Ludwig van Beethoven, c. 1812. The Wellcome Collection, London.

-

Life mask of Abraham Lincoln by Leonard Volk, 1860

-

Mask wearing customers in downtown Budapest.

-

From the picture album "Shunyū bijo no yukaeri", 19th Century

-

Performers with masks, mosaic, House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii

-

Mask of Silen, bronze, first half of the 1st century BC

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The oldest known example of the Venus figurines is the Venus of Hohle Fels, carbon-dated as 35,000 to 40,000 years old.

- ^ A famous example is the images of the Trois-Frères cave (circa 15,000 years old). According to John W. Nunley, "The earliest evidence of masking comes from the Mousterian site of Hortus in the south of France. There the archaeologist Henry de Lumley found remnants of a leopard skin that was probably worn as a costume more than 40,000 years ago" (Nunley, 1999, p. 22).

- ^ Pernet emphasizes that masks are not a wholly universal cultural phenomenon, raising the question why some cultures do not have a masking tradition.

References

[edit]- ^ "mask (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. n.d. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ von Wartburg, Walther (1992). Französisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch: Eine Darstellung galloromanischen sprachschatzes. Basel: Zbinden Druck und Verlag. ISBN 978-2745309372. OCLC 3488833.

- ^ Kupferblum, Markus (2007). "Menschen, masken, Charaktere: the Arbeit mit Masken am Theater". In Kreissl, Eva (ed.). Die Macht der Maske. Weitra, Austria: Bibliothek der Provinz Verlag für Literatur, Kunst und Musikalien. pp. 165, 193n. ISBN 978-3852528205.

- ^ Pernet, Henry (1992). Ritual Masks: Deceptions and Revelations. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9780872497931. LCCN 91045396.

- ^ Dall, William Healey (2010) [1884], "On masks, labrets, and certain aboriginal customs, with an inquiry into the bearing of their geographical distribution", Bureau of American Ethnology, Annual Report, vol. 3, Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 73–151

- ^ Klemm, Harald; Winkler, Reinhard (1996). Masken. Gesichter hinter dem Gesicht: Persönlichkeitsentfaltung und Therapie in der Arbeit mit Masken [Masks. Faces Behind the Face: Personality Development and Therapy in Working with Masks] (in German). Oberhofen: Zytglogge-Verlag. ISBN 978-3729605121.

- ^ Hitchcock, Don (6 October 2019). "Other Mousterian (Neanderthal) Sites". Don's Maps.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (2 December 2003). "Neanderthal 'face' found in Loire". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Guénon, René (2004). Symbols of Sacred Science. Hillsdale, New York: Sophia Perennis. p. 141.

- ^ Forbes, Jamie Ellin (Spring 2010). "The resurrection of the beauty of Spring: Jeanette Korab at Carnevale de Venezia". Fine Art Magazine. p. 21.

- ^ Danan, Julie Hilton (21 March 1997). "Purim wears many masks". Jewish News of Greater Phoenix. Vol. 49, no. 27. Archived from the original on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

...in many parts of the world and throughout Jewish history it was the time for adults to engage in masquerade.

- ^ Pannier, François; Mangin, Stéphane (1989). Masques de l'Himalaya, du primitif au classique. Paris: Editions Raymond Chabaud. p. 44.

- ^ Bradley, Lisa; Chazot, Eric (1990). Masks of the Himalayas. New York: Pace Primitive Gallery.

- ^ Blanc, Dominique; d'Hauterives, Arnaud; Geoffroy-Schneiter, Bérénice; Pannier, François (2009). Masks of the Himalayas. Milan: 5 Continents Editions.

- ^ Charette, Phillip John (n.d.). "About Yup'ik Masks". Phillip Charette, Contemporary Art in the Yupik Tradition. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010.

- ^ Fienup-Riordan, Ann (1996). The Living Tradition of Yup'ik Masks: Agayuliyararput (Our Way of Making Prayer). University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295975237. LCCN 95023296.

- ^ Lubin, David M. (Fall 2008). "Masks, Mutilation, and Modernity: Anna Coleman Ladd and the First World War". Archives of American Art Journal. 47 (3/4). Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution: 4–15. doi:10.1086/aaa.47.3_4.25435155. S2CID 192771456.

- ^ Edson, Gary (2005). Masks and Masking: Faces of Tradition and Belief Worldwide. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. ISBN 9780786421183.

- ^ Gregor, Joseph (2002). Masks of the World. Dover Publications. LCCN 68-18150.

- ^ Herold, Erich (1992). The World of Masks. Hamlyn. ISBN 9780600574422.

- ^ Kak, Subhash (2004). "Ritual, masks, and sacrifice". Studies in Humanities and Social Services. 11. Shimla, India: Indian Institute of Advanced Study.

- ^ a b Revelard, Michel; Kostadonova, Guergana (2000). Masques du Monde... L'univers du Masque Dans les Collections du Musée International du Carnaval et du Masque de Binche [Masks of the World... The Universe of Masks in the Collections of the International Museum of Carnivals and the Binche Mask] (in French). Tournai, Belgium: La Renaissance du Livre. ISBN 2-8046-0413-6.

- ^ Griffith, Jeremy (2013). Freedom Expanded: Book 1 – The Human Condition Explained. WTM Publishing & Communications. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-74129-011-0.

- ^ Lommel, Andreas (1981) [1970]. Masks: Their Meaning and Function. London: Ferndale Editions. p. Introduction, after Himmelheber Afrikanische Masken. ISBN 0-905746-11-2.

- ^ Ray, Benjamin C. "Faces of the Spirits". Department of Religious Studies, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ Bortolot, Alexander Ives (October 2003). "Idia: The First Queen Mother of Benin". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ^ Kahler, Wendy (16 May 1986). "African mask symbolism". Pagewise, Inc. Archived from the original on 5 February 2004. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ Lommel (1970), chapter: "Oceania: Melanesia, Polynesia, Australia".

- ^ Rainier, Chris; Taylor, Meg (1996). Where the Masks Still Dance: New Guinea. Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown & Co. ISBN 0-8212-2261-9.

- ^ Fienup-Riordan, Ann (1996). The Living Tradition of Yup'ik Masks: Agayuliyararput. The Anchorage Museum. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97501-6 – via Google books.

- ^ Feder, Norman (1973). American Indian Art. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams. LCCN 73-4857.

- ^ "Masks from North America, from the Edward S. Curtis Collection". Gallery. American Ethnography (americanethnography.com). Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ "Spotlight on El Santo". Professional Wrestling Online Museum. 5 February 1984. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ Lommel (1970), chapter: "South America/Central America".

- ^ a b Emigh, John (1996). Masked Performance. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1336-X.

- ^ Lommel (1970), chapter: "Japan".

- ^ Floor, Willem (2005). The History of Theater in Iran. MAGE. ISBN 0-934211-29-9.

- ^ Roze, Inese (4 April 2013), LAUKU CEĻOTĀ – Praktiskais seminārs: "Masku tradīcijas latviešu kultūrā" [COUNTRY TRAVEL – Practical seminar: "MASK TRADITIONS IN LATVIAN CULTURE"] (PDF) (in Latvian), Latvian Country Tourism Association, retrieved 26 February 2016

- ^ a b Poppi, Cesayo (1994). "The other within: masks and masquerades in Europe". In Mack, John (ed.). Masks: the Art of Expression. British Museum. ISBN 0-7141-2507-5.

- ^ Lommel (1970), chapter: "Europe/Conclusion".

- ^ Auguet, Roland (1975), Festivals and Celebrations, Collins, LCCN 73-15299

- ^ "Cornell University Library Digital Collections". Digital Collections. Cornell University Library.

- ^ a b c Callery, Dympha (2001). Through the Body: A Practical Guide to Physical Theatre. London: Nick Hern Books. ISBN 9781315059785. LCCN 2002510526.

- ^ Bablet, Denis (1981). The Theatre of Edward Gordon Craig. London: Eyre Methuen. ISBN 0413-4788-07.

- ^ Smith, Susan Harris (1984). Masks in Modern Drama. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05095-9.

- ^ Rudlin, John (1999). "3: Jacques Copeau: the quest for sincerity". In Hodge, Alison (ed.). 20th Century Actor Training. Routeledge.

- ^ Lecoq, Jacques (2002). The Moving Body: Teaching Creative Theatre. Routeledge. ISBN 978-1408111468.

- ^ Shank, Theodore (1982). American Alternative Theatre. Macmillan Modern Dramatists. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-28883-1.

- ^ Frith, Bob (2008). Veil. Horse + Bamboo Theatre. ISBN 978-0-9558841-0-8.

- ^ Aitchison, Sean (12 May 2017). "The 15 COOLEST Masks In Comics". CBR. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ "plaguedoctor". Discovery Channel Canada. Archived from the original on 16 October 2006.

- ^ Brandt, Stacy (12 October 2008). "Who Was That Masked Man?". The Daily Aztec. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009.

- ^ Solbakken, Per Kristian (10 February 2019). "damselfrau: a peek behind the many masks of the london-based artist". designboom. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ "Kanye West perfected the art of the face mask as a fashion accessory. Here's how". GQIndia. 24 August 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ Bryson, Kevin (20 May 2023). "Evaluating Anti-Facial Recognition Tools News Physical Sciences Division The University of Chicago". physicalsciences.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Burch, Ernest S. (junior); Forman, Werner (1988). The Eskimos. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2126-2.

- Hessel, Ingo; Hessel, Dieter (1998). Inuit Art. An introduction. foreword by George Swinton. 46 Bloomsbury Street, London WCIB 3QQ: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-2545-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Huteson, Pamela Rae (2007). Transformation Masks. Hancock House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-88839-635-8.

- Kleivan, Inge; B. Sonne (1985). Eskimos: Greenland and Canada. Iconography of religions, section VIII, "Arctic Peoples", fascicle 2. Leiden, The Netherlands: Institute of Religious Iconography • State University Groningen. E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-07160-1.

- Mauss, Marcel (1979) [c1950]. Seasonal variations of the Eskimo: a study in social morphology. in collab. with Henri Beuchat; translated, with a foreword, by James J. Fox. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-415-33035-1.

- Oosten, Jarich G. (1997). "Cosmological Cycles and the Constituents of the Person". In S. A. Mousalimas (ed.). Arctic Ecology and Identity. ISTOR Books 8. Budapest • Los Angeles: Akadémiai Kiadó • International Society for Trans-Oceanic Research. pp. 85–101. ISBN 963-05-6629-X.

- Rasmussen, Knud (1926). Thulefahrt. Frankfurt am Main: Frankurter Societăts-Druckerei.

- Rasmussen, Knud (1965). Thulei utazás. Világjárók (in Hungarian). translated by Detre, Zsuzsa. Budapest: Gondolat. Hungarian translation of Rasmussen 1926.

- Sivin, Carole (1986). Maskmaking. Worcester, Massachusetts, USA: Davis Publications. ISBN 978-0-87192-178-9.

- Wilsher, Toby (2007). The Mask Handbook: A Practical Guide. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41436-4.

External links

[edit]- Ritual, Masks, and Sacrifice (archived 26 July 2014)

- The Mythic Mask: mask history and contemporary mask art (archived 11 November 2006)

- The Noh Mask Effect: A Facial Expression Illusion

- Mask Makers of Mas, Bali (video on YouTube)

- Smithsonian Institution African Mask Links[permanent dead link]

- Virtual Museum of Death Mask Archived 8 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Gallery of Masks from Around the World Archived 18 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Costa Rica Traditional Face Mask

Etymology

Linguistic Origins and Evolution

The English word "mask" first appeared in the 1530s, borrowed from Middle French masque, denoting a covering to conceal or protect the face, often in the context of theatrical or festive disguises.[9] This French term, in turn, derives from Italian maschera, which carried similar meanings of a face disguise or satirical representation, reflecting its association with commedia dell'arte performances emerging in 16th-century Italy.[9] [10] The borrowing into English coincided with the popularity of court masques under Henry VIII and later Tudor entertainments, where the term adapted to describe elaborate facial coverings used in dramatic interludes.[9] The origins of Italian maschera remain debated among philologists, with no consensus on a single precursor. One hypothesis traces it to medieval Romance forms like Provençal mascarar or Catalan mascarar, meaning "to blacken the face" (as in smearing with soot for disguise), possibly evolving from Old French mascurer through vernacular speech in southern Europe.[11] [12] An alternative theory posits influence from Arabic maskharah ("buffoon" or "mockery"), derived from sakhira ("to ridicule"), introduced via Islamic Spain or Sicilian trade routes during the medieval period, though direct attestation is lacking and the connection relies on phonetic and semantic parallels rather than documented borrowing.[11] Less supported is a link to Latin masca ("witch" or "specter"), which denoted a malevolent face-like entity in late antiquity but lacked the covering connotation until later reinterpretations.[12] Semantically, the term expanded in European languages during the Renaissance, shifting from ritualistic or theatrical concealment—tied to carnival traditions in Venice and France by the 14th-15th centuries—to broader notions of obfuscation, as in the verb "to mask" (first attested in English around 1570), implying deliberate hiding of features or intentions.[9] This evolution paralleled the diffusion of masking customs across Romance and Germanic tongues, with cognates like German Maske (17th century) and Spanish máscara (16th century) adopting the Italianate form, underscoring the word's trajectory as a cultural loanword rather than a native Indo-European inheritance.[12] No Proto-Indo-European root directly underlies maschera, distinguishing it from indigenous terms for face coverings in older IE branches, such as Sanskrit mukhá ("face," from PIE *múk-).[9]Historical Development

Ancient and Pre-Modern Masks

The earliest indications of mask use emerge from Paleolithic cave art in Europe, featuring therianthropic (human-animal hybrid) figures dated to around 30,000–35,000 years ago, such as those in Chauvet Cave, France, which archaeologists interpret as evidence of shamanic rituals involving animal disguises or masks to invoke spirits or facilitate trance states for hunting success or communal survival rites.[13][14] These depictions, lacking physical artifacts, suggest masks functioned symbolically in early human societies to bridge the natural and supernatural, potentially aiding group cohesion during existential threats like scarcity, though direct causal efficacy in survival remains unprovable without ethnographic parallels. The oldest surviving physical masks are Neolithic stone carvings from the Judean Desert in present-day Israel, dated to approximately 7000–9000 BCE (Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period), crafted from local limestone with stylized human features including pierced eyes and mouths, likely employed in ancestor cults, fertility rituals, or shamanic ceremonies rather than practical disguise or protection.[15][16] In broader ancient contexts, such as Sumerian or Egyptian rituals circa 3000 BCE, masks of wood, cloth, or metal represented deities or the dead in funerary and initiation rites, emphasizing transformation over empirical utility, with no verified role in warding off environmental hazards beyond cultural placebo effects. By the late medieval period, masks entered rudimentary medical practice during bubonic plague epidemics, notably the Black Death (1347–1351 CE) and recurring outbreaks through the 17th century, when physicians like Charles de Lorme formalized the "plague doctor" attire in 1619, including a waxed linen overcoat and a prominent beak-shaped mask extending 15–20 cm from the face.[17][18] The beak, stuffed with herbs like lavender, cloves, and camphor, aimed to filter "miasma"—foul vapors theorized since Hippocratic times (circa 400 BCE) to cause putrefaction and disease—reflecting a pre-germ theory worldview where corruption of air, not pathogens, drove contagion.[19] Empirically, these masks offered negligible protection against Yersinia pestis, the plague bacterium transmitted via flea bites (bubonic form) or respiratory droplets (pneumonic form, responsible for up to 10–20% of cases); the loose-fitting design and herbal filling provided no microbial barrier, as confirmed by modern retrospective analyses, though the full ensemble may have incidentally reduced direct contact with infected fluids or fleas.[17][20] Survival rates among plague doctors varied, with many succumbing despite precautions, underscoring the masks' primary roles as psychological bulwarks against fear and symbolic adherence to humoral balance rather than causal intervention in disease transmission.[21]Emergence in Medicine and Protection

In the mid-19th century, early formalized respiratory protection emerged in industrial contexts to shield workers from airborne hazards. Lewis P. Haslett received U.S. Patent 6,529 on June 12, 1849, for his "Inhaler or Lung Protector," a device designed to filter dust, smoke, and noxious particles inhaled by painters, miners, and others exposed to contaminated air, marking one of the first patented efforts to create a reusable barrier for occupational safety.[22] This invention relied on a bellows-like mechanism with absorbent materials, reflecting growing recognition of inhalation risks in dusty environments, though its efficacy was limited by rudimentary filtration.[23] The shift toward medical applications accelerated in the late 19th century amid advances in bacteriology, which identified respiratory droplets as vectors for infection. German hygienist Carl Flügge demonstrated in 1897 that pathogens could spread via airborne droplets expelled during speech and coughing, providing empirical evidence that prompted surgeons to experiment with barriers to reduce contamination in operating theaters.[24] This causal understanding—linking droplet emission to wound sepsis—drove the transition from informal coverings to structured masks, prioritizing source control over ad hoc practices.[25] Polish surgeon Jan Mikulicz-Radecki, working in Breslau (now Wrocław), pioneered the modern surgical mask in 1897 by introducing gauze barriers worn over the mouth and nose to block droplet-borne bacteria from reaching surgical sites.[24] His innovation, often a multi-layer gauze pad secured to the face, was motivated by observations of postoperative infections and early tests showing reduced bacterial counts in masked environments; Mikulicz also advocated sterile gloves, integrating masks into aseptic protocols.[26] These masks targeted surgeon-to-patient transmission, with initial adoption in European clinics verifying lower infection rates through bacteriological sampling of air and wounds.[25] By the 1910s and 1920s, gauze surgical masks gained routine use in operating rooms across Germany and the United States, supported by accumulating evidence from controlled studies demonstrating their role in curbing droplet dispersion of bacteria like Staphylococcus and Streptococcus.[27] German surgeon Martin Kirschner and U.S. pioneers such as those at Johns Hopkins formalized masking in aseptic surgery, with bacteriologic assays confirming masks filtered over 90% of exhaled microbes in some setups, though debates persisted on fit and material durability.[28] This era's adoption emphasized empirical validation over tradition, distinguishing medical masks from industrial predecessors by focusing on sterile, disposable gauze to minimize cross-contamination in high-stakes procedures.[26]20th-Century Advancements and Public Health Applications

During World War I, the advent of chemical warfare necessitated rapid innovations in respiratory protection, leading to the development of advanced gas masks. The British Small Box Respirator, introduced in August 1916, marked a pivotal advancement with its rubberized fabric facepiece connected via a hose to a canister containing activated charcoal layers for adsorbing toxic gases such as chlorine and phosgene.[29] [30] This design improved upon earlier hoods by providing reliable filtration and became standard issue for British Empire forces by spring 1917.[29] Activated carbon filtration, building on Russian chemist Nikolay Zelinsky's 1915 charcoal-based prototype capable of neutralizing a range of chemical agents, enabled effective protection against evolving battlefield threats.[31] The 1918 influenza pandemic prompted early public health applications of masks in the United States, where cities enacted ordinances to promote widespread use amid inconsistent compliance. In San Francisco, mask-wearing became mandatory in late 1918, enforced through fines and public shaming of "mask slackers," though a second ordinance in January 1919 faced organized defiance and low adherence.[32] [33] Public health officials in affected areas, including Oakland and Seattle, advocated masks as a pragmatic measure to sustain urban functions while curbing transmission, yet enforcement varied by locality, with some jurisdictions publishing non-compliers' names in newspapers.[34] [35] These campaigns represented one of the first large-scale civilian mobilizations for mask use in Western public health responses to respiratory illness. Post-World War II industrialization drove further refinements in mask design for occupational hazards, with the U.S. Bureau of Mines establishing the first federal respirator certification program in 1919 to address dust and particulate risks in mining and manufacturing.[36] By the 1950s, standards emerged for protection against atmospheric contaminants like asbestos fibers, mandating respirators with improved particle filtration in high-risk industries.[37] Precursors to modern particulate respirators included 3M's 1961 patented lightweight disposable masks with elastic headbands, designed for medical and dust exposure settings.[38] The N95 respirator, developed by 3M and certified under NIOSH standards in the 1970s, achieved 95% efficiency against non-oil-based airborne particles, initially targeting industrial applications such as asbestos abatement and silica dust control.[39] These developments laid groundwork for standardized public health and occupational protections by emphasizing disposable, high-filtration materials.[40]Cultural and Ritual Uses

Masks in Performance and Theatre

In ancient Greek tragedy, originating in the 5th century BCE during festivals honoring Dionysus, actors wore oversized masks constructed from materials such as linen, wood, or cork, painted to exaggerate facial features for visibility in large amphitheaters seating up to 15,000 spectators.[41] These masks featured open mouths functioning as rudimentary megaphones to amplify the actor's voice across the open-air venues, while their fixed expressions denoted character types, ages, genders, and emotional states, enabling a single actor—typically one of three males—to portray multiple roles by swift mask changes without altering costumes significantly.[42] This technique emphasized archetypal representation over individual psychology, allowing the chorus and protagonists to convey universal tragic themes to distant audiences. During the Renaissance in 16th-century Italy, commedia dell'arte troupes employed half-masks made of leather or cartapesta to define stock characters like Harlequin (Arlecchino), Pantalone, and the Zanni servants, facilitating improvisation within lazzi—standard comic routines—while leaving the mouth free for agile dialogue and physical comedy.[43] These masks, often grotesque and regionally stylized, codified social types such as the miserly old man or cunning servant, promoting ensemble dynamics in performances that toured Europe until the 18th century and influenced later forms like pantomime.[44] The masks' durability and expressiveness supported rapid scene shifts and character consistency, contrasting scripted drama by prioritizing physicality and audience interaction over naturalistic facial cues. In Japanese Noh theatre, formalized in the 14th century by Zeami Motokiyo, wooden masks carved with subtle asymmetries allow skilled performers to alter perceived expressions through precise head tilts: upward (terasu) to simulate joy by catching light on carved smiles, or downward (kumorasu) to evoke sorrow via shadowing. This technique, combined with slow, grounded movements, conveys layered emotions from a neutral base, maintaining historical continuity from medieval rituals into professional performance while demanding actors relinquish personal expressiveness for the mask's illusory depth.[45] Twentieth-century experimental theatre revived masks in works by directors like Jacques Lecoq and in mime traditions descending from commedia, using them to externalize gesture and archetype amid reactions against psychological realism.[46] Proponents argued masks heightened stylized emotion and universality, as in Lecoq's neutral mask training for physical neutrality before character building, yet critics like those favoring Stanislavski's system contended they obscured authentic emotional vulnerability, prioritizing collective symbolism over individual actor-audience empathy.[47] This tension underscores masks' enduring role in challenging naturalistic conventions, fostering expressive techniques that prioritize form and tradition over unmediated facial authenticity.Regional Ceremonial Traditions

In West Africa, Dogon communities in Mali employ wooden masks during sacred dama funeral rituals and initiation ceremonies to invoke ancestral spirits, facilitating communal renewal and alignment with cosmological cycles that underpin agricultural practices.[48] These masks, often carved from specific woods like marula for symbolic potency, embody sigi and other rites where dancers channel supernatural forces to ensure fertility and social harmony, though ethnographic interpretations vary due to interpretive challenges in early French studies.[49] In Asia, Japanese Noh theatre, formalized in the mid-14th century during the Muromachi period, utilizes wooden masks to depict ghosts, deities, and warriors, enabling performers to transcend human expression through stylized tilts that alter perceived emotions via shadow and angle.[50] Similarly, Korean Hahoe tal masks feature in byeolsingut talnori performances, a shamanic tradition tracing to at least the Goryeo era, where grotesque carvings satirize officials and exorcise malevolent spirits to purify villages and appease guardian deities.[51] Indian tribal groups, such as those in central and northeastern regions, integrate masks into harvest dances and spirit invocations, where they serve as conduits for ancestral mediation in animist rites, preserving social cohesion amid historical syncretism with Hindu elements.[52] Among Northwest Coast indigenous peoples, Kwakwaka'wakw transformation masks—intricately carved to open revealing inner forms like thunderbirds—feature in potlatch ceremonies to affirm clan hierarchies and supernatural transformations, with dancers animating them via strings to embody ancestral power.[53] Colonial prohibitions from 1884 to 1951 disrupted these practices, leading to suppressed authenticity in surviving artifacts and performances, as Christianization and artifact confiscations altered ceremonial continuity and material traditions.[4] In Latin America, Mexican calavera masks, typically wooden skulls painted vibrantly, are donned during Día de los Muertos observances on November 1-2 to symbolize mortality and facilitate dances honoring the deceased, blending pre-Columbian indigenous ancestor veneration with Catholic All Saints' customs.[54] European folk traditions persist in Italy's Venetian carnival, where the bauta—a white, chin-extending mask permitting speech and eating—has been documented since the 13th century, originally enabling anonymous social leveling during pre-Lenten festivities before state regulations curtailed excesses by the 18th century.[55]Functional Applications

Protective and Occupational Masks

Protective masks in occupational settings are designed to shield workers from airborne hazards such as dust, fumes, and particulates, excluding biological agents. Half-face respirators, covering the nose and mouth, emerged prominently post-1970s with models like 3M's reusable elastomeric designs equipped with particulate filters for substances including silica dust.[56] These devices achieve an assigned protection factor (APF) of 10, meaning they reduce contaminant exposure to one-tenth of ambient levels when properly fitted and used.[57] In industries prone to silica exposure, such as construction and mining, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) mandates respiratory protection when exposures exceed the permissible exposure limit (PEL) of 50 micrograms per cubic meter over an 8-hour shift, established in 2016.[58] Employers must select NIOSH-approved respirators, conduct fit testing, and implement programs ensuring maintenance and training to comply with standards under 29 CFR 1910.134.[59] Half-face models with high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters effectively capture respirable crystalline silica particles, reducing inhalation risks associated with silicosis and lung cancer.[60] In recreational and sports contexts, masks provide impact protection against physical hazards. Baseball catchers' masks, standardized since the early 1900s following initial adoption in the late 19th century, consist of wire cages or polycarbonate shells mounted on padded helmets to deflect foul tips and wild pitches.[61] Empirical testing demonstrates these masks attenuate head accelerations from impacts by approximately 85%, significantly lowering risks of facial fractures and concussions compared to unprotected exposure.[62] Firefighting operations integrate masks within self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) systems, delivering clean air from cylinders to facepieces that seal against toxic smoke and oxygen-deficient environments. SCBAs weigh up to 35.25 pounds (16 kg) fully loaded, as limited by federal regulations, but this bulk impairs mobility, dynamic balance, and joint kinematics during tasks like crawling or stair ascent.[63] Studies indicate added SCBA mass elevates physiological strain, reduces work output, and heightens fatigue, prompting critiques that current designs prioritize respiratory integrity over ergonomic optimization in confined spaces.[64][65] Despite these limitations, SCBAs have enabled extended interior operations, correlating with decreased smoke inhalation injuries since their widespread NFPA-standardized adoption in the 1970s.[66]Medical and Hygienic Masks

Surgical masks, also known as medical procedure masks, emerged in operating rooms in Germany and the United States during the 1920s to reduce the risk of surgical site infections by containing exhaled droplets from healthcare personnel.[27] These masks typically consist of three layers of non-woven polypropylene material, with pleats for conformability and ties or ear loops for securing to the face.[67] In the United States, performance standards are defined by ASTM International's F2100 specification, which classifies masks into three levels based on bacterial filtration efficiency, differential pressure (breathability), and fluid resistance to synthetic blood penetration.[68] Level 1 masks offer the lowest fluid resistance (80 mmHg), suitable for general procedures with minimal splash risk; Level 2 provides moderate resistance (120 mmHg) for low-to-moderate fluid exposure; and Level 3 offers the highest (160 mmHg) for high-risk scenarios involving heavy fluid splatter.[69] In healthcare protocols, surgical masks are mandated during invasive procedures such as endotracheal intubation, bronchoscopy, or surgery to shield personnel from large-particle droplets, splashes, sprays, or splatter potentially containing pathogens.[70] For instance, during intubation, masks are paired with eye protection or face shields to form a barrier against aerosolized bodily fluids, adhering to guidelines from bodies like the CDC for standard precautions in patient care environments.[71] Masks must be donned prior to entering sterile fields or patient proximity zones and discarded after single use or if contaminated, with proper fit ensuring coverage of nose and mouth without gaps.[72] Hygienic cloth masks, often fabricated from cotton or similar fabrics in multiple layers, serve as alternatives in resource-limited healthcare settings where disposable surgical masks are scarce, enabling reuse to maintain basic barrier functions amid supply constraints.[73] These are typically laundered and disinfected between uses via boiling, autoclaving, or chemical agents to mitigate contamination risks, though empirical studies highlight challenges such as persistent bacterial colonization if decontamination is inadequate.[74] Protocols in such contexts emphasize daily replacement or rotation of multiple masks to prevent microbial buildup, with designs incorporating adjustable ties for better sealing in diverse facial anatomies.[75]Disguise, Sports, and Other Practical Uses

Masks have been employed for disguise to conceal identity during criminal activities throughout history. In the 19th-century American West, outlaws commonly wore bandanas or similar coverings over their faces during bank and train robberies to obscure their features, as documented in contemporary accounts and a 1901 news report confirming the practice's prevalence.[76] Similarly, European highwaymen in the 17th and 18th centuries utilized masks to hide their identities while committing robberies on public roads, enhancing the mystique and difficulty of apprehension.[77] In contemporary settings, balaclavas and similar full-face coverings are used by protesters to maintain anonymity amid potential surveillance or identification risks. Such masks facilitate anonymous participation in demonstrations, shielding wearers from facial recognition technology and legal repercussions, though they have also been associated with evading accountability for violent acts during unrest.[78][79] Anti-mask laws in various jurisdictions aim to deter their use in intimidating or criminal contexts by mandating facial visibility.[80] In sports, masks provide targeted protection during recreational or competitive activities emphasizing agility and precision. Fencing masks, invented in the mid-18th century by French master Texier de la Boëssière, feature wire mesh to safeguard the face from blade impacts while allowing visibility, revolutionizing the sport by enabling safer, faster techniques.[81] Ice hockey goaltenders adopted protective masks starting in 1959, when Jacques Plante introduced a fiberglass model during an NHL game, reducing facial injuries from high-speed pucks and evolving into hybrid designs combining cages and shells for enhanced coverage.[82][83] Other practical applications include specialized visors and veils for hobbyist pursuits involving environmental hazards. Welding visors, equipped with darkened filters, prevent over 50% of arc-related eye and face injuries by blocking ultraviolet radiation and flying debris, with studies showing significant reductions in foreign body incidents when combined with respiratory features.[84][85] Beekeeping veils, typically mosquito netting over hats, substantially lower facial sting risks by creating a physical barrier, though no gear offers complete immunity as bees may penetrate gaps or sting through thin fabric.[86][87]Scientific Evaluation of Efficacy

Mechanisms of Filtration and Protection