Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

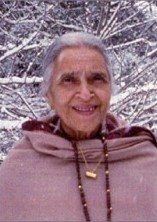

Shivani

View on Wikipedia

Gaura Pant (17 October 1923[1] – 21 March 2003), better known as Shivani, was a Hindi writer of the 20th century and a pioneer in writing Indian women-centric fiction. She was awarded the Padma Shri for her contribution to Hindi literature in 1982.[2]

Key Information

She garnered a following in the pre-television era of 1960s and 1970s, and her literary works such as Krishnakali, were serialised in Hindi magazines like Dharmayug and Saptahik Hindustan.[3] During the career, she wrote over 30 novels, prominently 'Bhairvi', 'Krishnakali', 'Chaudhan Phere', 'Atithi', 'Kalindi' and 'Akash'.[4] Through her writings, she also made the culture of Kumaon known to the Hindi speakers in India. Her novel Kariye Chima was made into a film, while her other novels including Surangma, Rativilaap, Mera Beta, and Teesra Beta have been turned into television serials.[5]

Early life

[edit]Gaura Pant 'Shivani' was born on 17 October 1923, the Vijaya Dasami day in Rajkot, Gujarat, where her father, Ashwini Kumar Pande was a teacher with the princely state of Rajkot. He was a Kumaoni Brahmin. Her mother was a Sanskrit scholar, and the first student of Lucknow Mahila Vidyalaya. Later her father became the Diwan with the Nawab of Rampur and the member of Viceroy's Bar Council,[6] thereafter the family moved to the princely state of Orchha, where her father held an important position. Thus Shivani's childhood had influences from these varied places, and an insight into women of privilege, which reflected in much of her work. At Lucknow, she became the first student of the local Mahila Vidyalaya Lucknow (Lucknow University).[7]

In 1935, Shivani's first story was published in the Hindi Children's magazine Natkhat, at age twelve.[8] That was also when the three siblings were sent to the study at Rabindranath Tagore's Visva-Bharati University at Shantiniketan. Shivani remained at Shantiniketan for another 9 years and left as a graduate in 1943. Her serious writings started during the years spent at Shantiniketan. It was this period that she took to writing whole-heartedly and had the most profound influence in her writing sensibilities,[9] a period she recounts vividly in her book, Amader Shantiniketan.[10]

Family

[edit]Shivani was married to Shuk Deo Pant, a teacher who worked in the Education Department of Uttar Pradesh, which led to the family travelling to various places including Allahabad and Priory Lodge in Nainital, before settling in Lucknow, where she stayed till her last days.[7] She had four children, seven grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Her husband died at an early age, leaving her to take care of the four children. She had three daughters, Veena Joshi, Mrinal Pande and Ira Pande, and a son Muktesh Pant[11]

Literary career

[edit]In 1951, her short story, Main Murga Hun ('I am a Chicken') was published in Dharmayug under the pen name Shivani. She published her first novel Lal Haveli in the sixties, and over the next ten years she produced several major works which were serialised in Dharmayug. Shivani received the Padma Shri for her contribution to Hindi literature in 1982.[2]

She was a prolific writer; her bibliography consists of over 40 novels, many short stories and hundreds of articles and essays. Her most famous works include Chaudah Phere, Krishnakali, Lal Haveli, Smashan Champa, Bharavi, Rati Vilap, Vishkanya, Apradhini. She also published travelogues such as Yatriki, based on her London travels, and Chareivati, based on her travels to Russia.[12]

Towards the end of her life, Shivani took to autobiographical writings, first sighted in her book, Shivani ki Sresth Kahaniyan, followed by her two-part memoir, Smriti Kalash and Sone De, whose title she borrowed from the epitaph of 18th-century Urdu poet Nazeer Akbarabadi:[13]

Shivani continued to write till her last days, and died on 21 March 2003 in New Delhi, after a prolonged illness.[4]

Death and legacy

[edit]Upon her death, the Press Information Bureau said that "the Hindi literature world has lost a popular and eminent novelist and the void is difficult to fill".[14]

In 2005, her daughter, Hindi writer Ira Pande, published a memoir based on Shivani's life, titled Diddi My Mother's Voice. Diddi in Kumaoni means elder sister, and that's how her children used to address her, as she really was a friend to them.[15] In 2021, IIT Kanpur established the Shivani Centre for the nurture and re-integration of Hindi and other Indian languages.[16][17] In 2023, making her birth centenary, a literary festival was organised at IIT Kanpur.[18]

Bibliography

[edit]- Chareiveti — A narrative of travel in Russia and her encounters with literary figures

- Atithi (1991) — A novel whose central character, Jaya, after a failed marriage meets Shekhar who proposes to her

- Pootonvali (1998) — A collection of two novelettes and three short stories

- Jharokha (1991)

- Chal Khusaro Ghar Aapne (1998)

- Vatayan (1999)

- Ek Thi Ramrati (1998)

- Mera Bhai/Patheya (1997) — A novella and her recollections of events and personages

- Yatrik (1999) — Her experiences in England where she travelled for the marriage of her son

- Jaalak (1999) — 48 short memoirs

- Amader Shantiniketan (1999) — Reminiscences of Shantiniketan

- Manik — Novellette and other stories (Joker and Tarpan)

- Shmashan Champa (1997)

- Surangma — A novel about a political figure and his personal life shadowed by sordid relationships

- Mayapuri — A novel about relationships

- Kainja — A novel and 7 short stories

- Bhairvee — A novel

- Gainda — A novel and two long stories

- Krishnaveni — A novelette and two short stories

- Swayam Sidha — A novel and 6 short stories

- Kariya Cheema — 7 short stories

- Up Preti — 2 short novels, a story and 13 nonfictional articles

- Chir Swayamvara — 10 short stories and 5 sketches

- Vishkanya — A novelette and 5 short stories

- Krishnakali — A novel

- Kastoori Mrig — A short novel and several articles

- Aparadhini — A novel

- Rathya — A novel

- Chaudah Phere — A novel

- Rati Vilap — 3 novelettes and 3 short stories

- Shivani ki Sresth Kahaniyan —13 short stories

- Smriti Kalash — 10 essays

- Sunhu Taat Yeh Akath Kahani — Autobiographical narratives

- Hey Dattatreya — Folk culture and literature of Kumaon

- Manimala Ki Hansi — Short stories, essays, memoirs and sketches

- Shivani ki Mashhoor Kahaniyan — 12 short stories[19]

English translations

[edit]- Trust and other stories. Calcutta: Writers Workshop, 1985.

- Krishnakali and other stories. Trans. by Masooma Ali. Calcutta: Rupa & Co., 1995. ISBN 81-7167-306-6.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ A Memoir, Ira Pande

- ^ a b Shivani Guara Pant Official Padma Shri List.

- ^ Shivani The Hindu, 4 May 2003

- ^ a b Gaura Pant Shivani dead The Tribune, 22 March 2003.

- ^ Shivani Profile www.abhivyakti-hindi.org.

- ^ Shivani Gaura Pant – Biography Biography at readers-café.

- ^ a b The stories of Kumaon..[dead link] Indian Express, 22 March 2003.

- ^ First story Archived 4 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine Biography at kalpana.it.

- ^ Shivani Archived 17 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine Deccan Herald, 23 July 2005.

- ^ "Calcutta years, kalpana". Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ Shivani Gaura Pant: A Tribute Archived 27 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gaura Pant Shivani, List of works

- ^ Lokvani interviews Shivani, 2002

- ^ Obituary, 2003 pib.nic.in.

- ^ Ira Pande remembers kamlabhattshow.com.

- ^ SHIVANI CENTRE FOR NURTURE AND REINTEGRATION OF HINDI AND OTHER INDIAN LANGUAGES IIT Kanpur Official website.

- ^ IIT Kanpur sets up Shivani Centre for the Nurture and Re-Integration of Hindi and Other Indian Languages Curriculum magazine, August 23, 2021.

- ^ Birth centenary festival of ‘Shivani’ celebrated The Times of India, Oct 18, 2023 .

- ^ Books of Shivani Archived 20 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine www.indiaclub.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Diddi, My Mother's Voice. Ira Pande, January 2005, Penguin. ISBN 0-14-303346-8.