Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

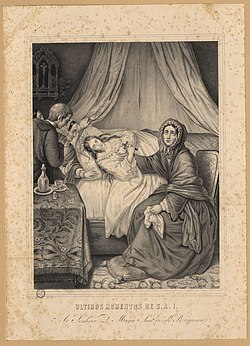

Last rites

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

The last rites, also known as the Commendation of the Dying, are the last prayers and ministrations given to an individual of Christian faith, when possible, shortly before death.[1] The Commendation of the Dying is practiced in liturgical Christian denominations, such as the Roman Catholic Church and the Lutheran Church.[2] They may be administered to those mortally injured, terminally ill, or awaiting execution. Last rites cannot be performed on someone who has already died.[3] Last rites, in sacramental Christianity, can refer to multiple sacraments administered concurrently in anticipation of an individual's passing (such as Holy Absolution and Holy Communion).[2][4]

Catholic Church

[edit]

The Latin Church of the Catholic Church defines last rites as Viaticum (Holy Communion administered to someone who is dying), and the ritual prayers of Commendation of the Dying, and Prayers for the Dead.[5]

The sacrament of Anointing of the Sick is usually postponed until someone is near death. Anointing of the Sick has been thought to be exclusively for the dying, though it can be received at any time. Extreme Unction (Final Anointing) is the name given to Anointing of the Sick when received during last rites.[6] If administered to someone who is not just ill but near death, Anointing of the Sick is generally accompanied by celebration of the sacraments of penance and Viaticum.

The order of the three is important and should be given in the order of penance (confessing one's sins), then Anointing of the Sick, and finally the Viaticum.[7] The principal reason penance is administered first to the seriously ill and dying is because the forgiveness of one's sins, and most especially one's mortal sins, is for Catholics necessary for being in a state of grace (in a full relationship with God). Dying while in the state of grace ensures that a Catholic will go to heaven (if they are in a state of grace but still attached to sin, they will eventually make it to heaven but must first go through a spiritual cleansing process called purgatory).

Although these three (penance, Anointing of the sick, and Viaticum) are not, in the proper sense, the last rites, they are sometimes spoken of as such; the Eucharist given as Viaticum is the only sacrament essentially associated with dying.[8] "The celebration of the Eucharist as Viaticum is the sacrament proper to the dying Christian".[9]

In the Roman Ritual's Pastoral Care of the Sick: Rites of Anointing and Viaticum, Viaticum is the only sacrament dealt with in Part II: Pastoral Care of the Dying. Within that part, the chapter on Viaticum is followed by two more chapters, one on Commendation of the Dying, with short texts, mainly from the Bible, a special form of the litany of the saints, and other prayers, and the other on Prayers for the Dead. A final chapter provides Rites for Exceptional Circumstances, namely, the Continuous Rite of Penance, Anointing, and Viaticum, Rite for Emergencies, and Christian Initiation for the Dying. The last of these concerns the administration of the sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation to those who have not received them.[10]

In addition, the priest has authority to bestow a blessing in the name of the Pope on the dying person, to which a plenary indulgence is attached.[11]

Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches

[edit]

In the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite, the last rites consist of the Sacred Mysteries (sacraments) of confession and the reception of Holy Communion.

Following these sacraments, when a person dies, there are a series of prayers known as The Office at the Parting of the Soul From the Body. This consists of a blessing by the priest, the usual beginning, and after the Lord's Prayer, Psalm 50. Then a Canon to the Theotokos is chanted, entitled, "On behalf of a man whose soul is departing, and who cannot speak". This is an elongated prayer speaking in the person of the one who is dying, asking for forgiveness of sin, the mercy of God, and the intercession of the saints. The rite is concluded by three prayers said by the priest, the last one being said "at the departure of the soul."[12]

There is an alternative rite known as The Office at the Parting of the Soul from the Body When a Man has Suffered for a Long Time. The outline of this rite is the same as above, except that Psalm 71 (70) and Psalm 144 (143) precede Psalm 51 (50), and the words of the canon and the prayers are different.[13]

The rubric in the Book of Needs (priest's service book) states, "With respect to the Services said at the parting of the soul, we note that if time does not permit to read the whole Canon, then customarily just one of the prayers, found at the end of the Canon, is read by the Priest at the moment of the parting of the soul from the body."[14]

As soon as the person has died the priest begins The Office After the Departure of the Soul From the Body (also known as The First Pannikhida).[15]

In the Orthodox Church Holy Unction is not considered to be solely a part of a person's preparation for death, but is administered to any Orthodox Christian who is ill, physically or spiritually, to ask for God's mercy and forgiveness of sin.[16] There is an abbreviated form of Holy Unction to be performed for a person in imminent danger of death,[16] which does not replace the full rite in other cases.

Lutheran Churches

[edit]In the Lutheran Churches, last rites are formally known as the Commendation of the Dying, in which the priest "opens in the name of the triune God, includes a prayer, a reading from one of the psalms, a litany of prayer for the one who is dying, [and] recites the Lord’s Prayer".[2] The dying individual is then anointed with oil and receives the sacraments of Holy Absolution and Holy Communion.[2]

Anglican Communion

[edit]The proposed 1928 revision of the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer would have permitted reservation of the Blessed Sacrament for use in communing the sick, including during last rites. This revision failed twice in the Parliament of the United Kingdom's House of Commons.[17]

In the Episcopal Church in the United States a rite is found in the 1979 Book of Common Prayer called the Ministration at the Time of Death. This rite consists of "a prayer for a person near death," a "litany at the time death" asking God to deliver the person from evil, sin, and tribulation and to grant them forgiveness, and peace. This litany is followed by the Lord's Prayer and a commendation of the Soul to God. After death prayers for the persons eternal rest are offered.

This rite is oftentimes administered alongside Unction, and Holy Communion.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of THE LAST RITES". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Liturgies for the end of life" (PDF). Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. 2017. p. 4. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Kerper, Rev. Fr. Michael (July–August 2016), vonHaack, Sarah J. (ed.), "When can Last Rites be given?", Dear Father Kerner, Parable, vol. 10, no. 1, Manchester, N.H.: Diocese of Manchester, pp. 10–11, USPS 024523, archived from the original on 6 May 2021, retrieved 15 November 2020,

The priest was correct: only a living person can receive a sacrament, including the sacrament of the sick.

- ^ Dotan Arad; Kathleen Ashley; Martin Christ; Hildegard Diemberger (10 December 2018). Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World. BRILL. p. 86. ISBN 978-90-04-37588-8.

- ^ "M. Francis Mannion, "Anointing or last rites?" in Our Sunday Visitor Newsweekly". Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church - The anointing of the sick". www.vatican.va.

- ^ Arnold, Michelle (29 December 2017). "A Guide to the Last Rites". Catholic Answers. Archived from the original on 4 June 2018.

- ^ Stolz, Eric. "Anointing of the Sick/Last Rites". St. Brendan Catholic Church. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Sacramental Guidelines" (PDF). Diocese of Gallup. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ "Other Sacraments – St Patrick's Catholic Parish Mortlake". stpatsmortlake.org.au. Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ Armentrout, Don S.; Slocum, Robert Boak (1999). An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church: A User-Friendly Reference for Episcopalians. Church Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89869-211-2.

- ^ Hapgood, Isabel Florence (1975), Service Book of the Holy Orthodox-Catholic Apostolic Church (Revised ed.), Englewood, NJ: Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese, pp. 360–366

- ^ A Monk of St. Tikhon's Monastery (1995), Book of Needs (Abridged) (2nd ed.), South Canaan PA: St. Tikhon's Seminary Press, pp. 123–136, ISBN 1-878997-15-7

- ^ A Monk of St. Tikhon's Monastery, Op. cit., p. 153.

- ^ A Monk of St. Tikhon's Monastery, Op. cit., pp. 137–154.

- ^ a b Hapgood, Op. cit., pp. 607–608.

- ^ Wohlers, Charles. "The Proposed Book of Common Prayer (1928) of the Church of England". Society of Archbishop Justus. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

External links

[edit]- Extreme Unction article in The Catholic Encyclopedia (1909)

- Preparation for Death article in The Catholic Encyclopedia (1909)

- Higgins, Jethro (6 March 2018). "Last Rites and the Anointing of the Sick". Oregon Catholic Press. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Sacramental Catechesis: An Online Resource for Dioceses