Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

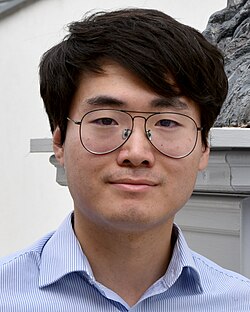

Simon Cheng

View on Wikipedia

Simon Cheng Man-kit (Chinese: 鄭文傑; born 10 October 1990) is a Hong Kong activist. He was formerly a trade and investment officer at the British Consulate-General in Hong Kong. Cheng was detained by Chinese authorities in August 2019 in West Kowloon station when he returned from a business trip in Shenzhen. Chinese government agents tortured Cheng to induce his confession on video that he was a British spy who was involved in instigating the 2019 Hong Kong protests. Cheng subsequently fled to London and was granted asylum in June 2020.

Key Information

Early life and career

[edit]Cheng was born in Hong Kong in 1990, and he was a Hong Kong permanent resident. He graduated from National Taiwan University with a degree in political science and pursued a M.Sc. in the Political Economy of Europe at the London School of Economics.

Cheng returned to Hong Kong in 2017 and worked as a trade and investment officer at the British Consulate-General Hong Kong. His work was in the Scottish Development International section with his main responsibility being to encourage the mainland business community to invest in Scotland.[1]

Detention in China

[edit]Disappearance

[edit]On 8 August 2019, Cheng, on behalf of the British Consulate-General of Hong Kong, left Hong Kong for Shenzhen to attend a business event via the Lo Wu control point. He was expected to return on the same day via the Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong Express Rail Link. At 10:37 pm that day, he messaged his Taiwanese girlfriend, indicating that he was about to pass through the border checkpoint in West Kowloon station, which is under Mainland China's jurisdiction despite the fact that the station itself is located in Hong Kong after the controversial co-location agreement was passed in the Legislative Council in 2018. However, his family and friends were unable to contact him, and he did not show up for work on the following day.[2] His family and friends worried that he was arrested because he had expressed his support for the ongoing 2019 Hong Kong protests through his social media accounts.[3]

On 14 August, a group of protesters gathered outside the UK consulate in Hong Kong to stand in solidarity with Cheng and asked the UK government to assist him. His disappearance caught public attention, since it was reported that officers at the border had been searching civilians' belongings and phones to identify anyone who had attended the protests.[3] China has also accused foreign powers including the United Kingdom of instigating the protests, though has failed to produce evidence to support such accusations.[4]

His family met with Nicola Barrett, a consulate official, who advised them to seek help from the police. The Hong Kong Police Force launched an investigation into the issue and listed Cheng as a "missing person". When asked by journalists from HK01, officers at the West Kowloon station checkpoint claimed that no one was arrested on 8 and 9 August inside the station. The Immigration Department also assisted Cheng's family and had contacted the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in Guangdong for more information and later reported on August 10 that Cheng was under administrative detention in Shenzhen, though the reason for detainment was not disclosed.[2] The British Consul General stated that they were "extremely concerned" about Cheng's disappearance and asked the Chinese authorities to release more details about his detainment.[5]

On 21 August, at a press conference held by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, spokesperson Geng Shuang revealed that China had detained Cheng using the Security Administration Punishment Law, which covers mostly minor offences. Geng added that his arrest was China's "internal affair" since Cheng was a Hong Kong citizen.[5] The following day, Chinese state-owned tabloid Global Times added that Cheng was arrested for allegedly "soliciting a prostitute". Under Article 66 of the law, offenders can be fined and detained for "no less than ten days but no more than fifteen days".[3] According to Hu Xijin, a Global Times editor, Cheng's family was not informed by the police because it was supposedly requested by Cheng to "...reduce damage to his reputation". However, Cheng's family rejected such accusations, telling Hong Kong Free Press that "Everyone knows it is not the truth. But time will tell". The family, who operated a Facebook page named "Release Simon Cheng" then re-posted the Global Times news piece on Facebook and added that the piece was "a joke".[6] Global Times had previously attacked Cheng for his political views and accused him of supporting Hong Kong independence.[7] On 24 August, he returned to Hong Kong.[8]

Recounting the incident

[edit]In November, Cheng published an article named "For the Record: An Enemy of the State" on Facebook, in which he disclosed the details during his detention and his side of the story. He admitted that the British consulate had asked him to observe the protests. He had joined several legal and peaceful rallies, and joined several Telegram groups which were used by the protesters for coordination. He stated that the protest movement was leaderless and all actions were coordinated using digital platforms. Cheng added that his role was to purely observe the movement then report back to the British consulate, meaning that he would not attempt to direct the movement or instigate any conflict. He further added that it was "the kind of civil society monitoring work many embassies do". He believed that his position as a member of the British consulate staff, as well as his relationship with a mainland Chinese friend who was detained for participating in the protests, were the main reasons why Chinese authorities chose to detain him. During his trip in Shenzhen, he met with the relatives of the friend and collected money for him in a private capacity.[1]

He recounted that he was handed over to three plain-clothed officers who he suspected to be secret police after he was escorted back to Shenzhen from West Kowloon station.[1][9] The mainland agents inquired about the UK's role in the protests, and questioned him about what kind of assistance the UK government had provided to the protesters. According to Cheng, they subjected him to torture in order to make him confess that he had instigated and organised the protests "on behalf of the British government". Cheng added that he was "shackled, blindfolded and hooded" during his detention. He was forced to maintain stress positions for a sustained period, and that he would be beaten when he moved. He also reported being subjected to solitary confinement and sleep deprivation, as interrogators forced him to sing the Chinese national anthem whenever he tried to sleep. He was also strapped on a "tiger chair", which completely disabled the movement of the detainees, for a sustained period of time. His glasses were removed throughout his detention, causing him to feel "dizzy" constantly, and he was not allowed to contact his family. He also believed that other Hongkongers were detained by China.[1]

Cheng added that the interrogators showed him pictures of protesters and asked him if he recognised any of them or if he was able to point out their political affiliation. He was also asked to draw out an organisation chart as the agents hoped to identify the protest leaders and "core" protesters. They also forced him to unlock his phone, allowing them to print out email conversations he had with the British consulate. The agents then forced him to record two confession videos, one for soliciting prostitutes, another for "betraying the motherland".[1] Throughout the process, the agents verbally assaulted him, calling him "worse than shit", "enemy of the state", and that he did not deserve any "human rights" as he was an "intelligence officer".[1][10] They also threatened that they would never release him, and claimed they would charge him for "subversion and espionage" if he refused to admit that the British were the masterminds behind the protests.[10][11] Commenting on the interrogators, Cheng believed that they were not keen on finding the truth, and wanted to "fulfil and prove their pre-written play by filling in the information they want from the detainees".[12] Before he was allowed to leave, the police reportedly threatened him by claiming that he would be "taken back" to mainland China from Hong Kong if he disclosed "anything other than 'soliciting prostitution' publicly".[1]

When asked by a reporter from BBC News if he paid for sex, Cheng said he visited a massage parlour for "relaxation" after his business trip, and that he had done "nothing regrettable to the people I cherish and love".[1] On 21 November, Chinese state media China Global Television Network (CGTN) released his confession video and a two-minute long CCTV footage of him visiting a clubhouse. CGTN claimed that the footage was taken on 23 July, 31 July and 8 August, and wrote that Cheng stayed in the parlour for approximately two and a half hours in each visit. In the confession video, wearing prison uniform, Cheng claimed that he did not contact his family or seek help from a lawyer because "he felt ashamed and embarrassed". Cheng, in his earlier written statement, added that he was forced to confess and that he had to record it several times.[13] Cheng stated that he recorded the video under duress and he was coerced into filming the video as a condition for his release.[11] He added that he would be put under "indefinite criminal detention" if he refused to film the video.[14] He filed a complaint to Ofcom over CGTN's broadcast of his forced confession on 28 November 2019.[15] On 4 February 2021, Ofcom revoked CGTN's licence to broadcast in the UK.[16] On 8 March 2021, CGTN was fined a total of £225,000 by Ofcom for serious breaches of fairness, privacy and impartiality rules. "We found the individuals (Simon Cheng and Gui Minhai) concerned were unfairly treated and had their privacy unwarrantably infringed," Ofcom said, adding that the broadcaster had "failed to obtain their informed consent to be interviewed." It concluded that "material facts which cast serious doubt on the reliability of their alleged confessions" had been left out of the programmes, which aired pre-trial "confessions" of the two men while they were being detained. Ofcom said it was considering further sanctions.[17]

Reactions

[edit]According to BBC News, UK government sources deemed his account about forced confession and torture credible, and the UK government had subsequently offered Cheng support. Dominic Raab, the Foreign Secretary, condemned the Chinese government and summoned Chinese ambassador Liu Xiaoming:[18]

Simon Cheng was a valued member of our team. We were shocked and appalled by the mistreatment he suffered while in Chinese detention, which amounts to torture. I summoned the Chinese Ambassador to express our outrage at the brutal and disgraceful treatment of Simon in violation of China's international obligations. I have made clear we expect the Chinese authorities to investigate and hold those responsible to account.[18]

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang criticised the summoning of Liu and responded by warning the UK not to interfere in China's internal affairs and describing the UK's "actions and comments on all issues relating to Hong Kong" as "false".[19][12] Liu also responded by saying that Cheng had already made the confession, and that his legal rights were protected during his detention.[20] Hong Kong's Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng declined to comment.[19]

Amnesty International responded by saying that Cheng's account of his treatment during his detention aligned with the "documented pattern of torture" commonly seen in Chinese prisons.[11] Peter Dahlin, who served as the director for Safeguard Defenders, commented that Cheng's confession videos have no validity. He added that Beijing has a history of forcing detainees who have ties with foreign governments to record confession videos to deflect criticism. He added that these videos "paint the process with a veneer of judicial process and legality".[13] Willy Lam, a professor from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, commented that the incident reflects Beijing's "vindictive attitude" towards Hong Kong citizens who have ties to foreign countries, and that the incident would likely further fuel the ongoing protests.[21]

Life after detention

[edit]After he returned to Hong Kong, Cheng claimed that he was "asked to resign" by the consulate as he was considered a "security risk", though the consulate responded by saying that it was Cheng's decision to resign.[10] Cheng later clarified that he left the post because his job would require him to visit mainland China frequently. He briefly stayed in Taiwan from 30 August to 29 November 2020. In Xinyi District, he found himself being followed by an unknown individual. The Taiwanese government then provided bodyguards for him to ensure his personal safety.[22]

The UK government granted him a two-year working holiday visa, and on 27 December 2019, he submitted a request for asylum, which was granted to him and his fiancée on 26 June 2020. This indicated that after five years, he would become eligible to apply for full British citizenship.[23] After he left Hong Kong, he advocated internationally for Hong Kong's and Taiwan's freedom and democracy. As China imposed a national security law on Hong Kong, Cheng collaborated with other exiled activists, including Ray Wong, Brian Leung and Lam Wing-kee to launch an online advice platform named "Haven Assistance" to help Hongkongers who were also facing political prosecution and seeking asylum.[24] Cheng also advocated for the establishment of a "parliament-in-exile" as he believed that the formation of such council can "send a very clear signal to Beijing and the Hong Kong authorities that democracy need not be at the mercy of Beijing".[25] He also established "Hongkongers in Britain", a platform which aids Hongkongers already in Britain and those who sought to emigrate there to integrate into the society.[26]

On 30 July 2020, the Hong Kong police announced that they had issued arrest warrants to six exiled activists including Cheng, Nathan Law, Ray Wong, Wayne Chan, Honcques Laus, and Samuel Chu for breaching the national security law "on suspicion of inciting secession or colluding with foreign forces". Responding to becoming a political fugitive, Cheng said "the totalitarian regime now criminalises me, and I would take that not as a shame but an honour".[27] On 14 December 2023, the Hong Kong government issued an arrest warrant against Cheng and put a bounty of HK$1 million on his capture.[28]

On 10 January 2024, Hong Kong national security police searched Cheng's parents' and two sisters' home and brought them to police stations for questioning. Cheng had broken off contact with his family for four years.[29] On 12 June 2024, the Hong Kong government revoked the passport of Cheng, exercising powers that it had been granted under the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Sudworth, John (20 November 2020). "Simon Cheng: Former UK consulate worker says he was tortured in China". BBC News. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b Cheng, Kris (20 August 2019). "China detains staff member from UK's consulate in Hong Kong for over 10 days after business trip". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Mackintosh, Eliza; George, Steve (23 August 2019). "British consulate employee detained for 'solicitation of prostitution,' Chinese state-run newspaper reports". CNN. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Tian, Long-lee (20 August 2019). "Girlfriend of U.K. Consulate Worker Says China Has Detained Him". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b Hollingsworth, Julia (21 August 2019). "Hong Kong: British consulate employee Simon Cheng detained in China". CNN. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Cheng, Kris (22 August 2020). "Family of detained British consulate staffer refutes Chinese state media's prostitution claim". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Zheng, Sarah (22 August 2019). "Britain in urgent quest for contact with Hong Kong consulate employee Simon Cheng Man-kit". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Tong, Elson (24 August 2019). "British consulate staffer Simon Cheng returns to Hong Kong after China detention". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Fan, Wenxin (21 November 2020). "Former U.K. Consulate Employee Says Chinese Secret Police Tortured Him". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Yu, Verna (20 November 2019). "Former UK employee in Hong Kong 'tortured in 15-day China ordeal'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Yan, Sophia (20 November 2019). "UK to grant visa to Hong Kong consulate worker tortured in China". The Telegram. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b Qin, Amy (20 November 2019). "Ex-Worker at U.K. Consulate in Hong Kong Says China Tortured Him". New York Times. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b Chan, Holmes (21 November 2019). "Chinese state media publish 'confession' video of former UK consulate staffer Simon Cheng". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "China releases video of UK consulate worker's confession to 'soliciting prostitution' amid torture allegations". Straits Times. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Simon Cheng: UK media watchdog receives 'China forced confession' complaint". BBC. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Ofcom revokes Chinese broadcaster CGTN's UK licence". BBC.

- ^ "Chinese state broadcaster CGTN fined £225,000 by UK regulator". Financial Times.

- ^ a b Faulconbridge, Guy (20 November 2020). "China tortured me over Hong Kong, says former British consulate employee". Reuters. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b Chan, Holmes (21 November 2019). "UK gov't summons China ambassador over 'torture' of former consulate staffer". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Chinese ambassador denies torture claims". RTHK. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Marlow, Iain (20 November 2019). "U.K. Accuses China of Torturing Hong Kong Consulate Worker". Time. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Chung, Li-hua; Hetherington, William (9 December 2019). "Simon Cheng says he was tailed in Taipei". Taipei Times. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (2 July 2020). "Simon Cheng, Hong Kong consulate worker 'tortured' in China, is granted UK asylum". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Wong, Rachel (3 July 2020). "UK grants exiled ex-consulate staffer Simon Cheng asylum as Hong Kong activists launch advice platform". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Natalie; Faulconbridge, Guy (2 July 2020). "Exclusive: Hong Kong activists discuss 'parliament-in-exile' after China crackdown". Reuters. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "鄭文傑創英國港僑協會 助港人英國重建生活 (10:36)". Ming Pao. 16 July 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Hong Kong 'seeking arrest' of fleeing activists". BBC. 31 July 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Leung, Hillary (14 December 2023). "Hong Kong national security police issue arrest warrants, HK$1 million bounties for 5 overseas activists". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ "流亡英國港人家人遭國安警帶走調查 鄭文傑盼望來生再見". 美國之音. 10 January 2024. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Grundy, Tom (12 June 2024). "Hong Kong cancels passports of 6 'fugitive' activists in UK, inc. Nathan Law, under new security law provision". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

Simon Cheng

View on GrokipediaSimon Cheng is a Hong Kong-born pro-democracy activist and former trade and investment officer at the British Consulate-General in Hong Kong.[1][2]

In August 2019, Cheng was detained by Chinese authorities at the Shenzhen border while returning from a business trip, held under administrative detention for 15 days on charges including "picking quarrels and provoking trouble" and alleged prostitution-related offenses.[3][4]

He later recounted being subjected to torture, including beatings and forced stress positions, during interrogations focused on his consulate work and support for Hong Kong's pro-democracy protests, prompting the UK government to condemn the mistreatment of its former staff member.[2][5]

Chinese officials released a video of Cheng confessing to the charges under duress and denied torture allegations, attributing his detention to violations of China's Security Administration Punishment Law. [6]

After his release and subsequent flight to the United Kingdom, Cheng was granted asylum in 2020 amid ongoing threats, establishing himself as a human rights advocate and co-founder of the diaspora organization Hongkongers in Britain to support exiled Hong Kongers and highlight transnational repression by Beijing.[7][8][1]

.jpg/250px-Simon_Cheng_(2022).jpg)

.jpg)