Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Snowbasin

View on Wikipedia

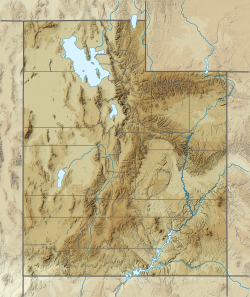

Snowbasin Resort is a ski resort in the western United States, located in Weber County, Utah, 33 miles (53 km) northeast of Salt Lake City, on the back (east) side of the Wasatch Range.[1]

Key Information

Opened 86 years ago in 1939,[1] as part of an effort by the city of Ogden to restore the Wheeler Creek watershed, it is one of the oldest continually operating ski resorts in the United States. One of the owners in the early days was Aaron Ross. Over the next fifty years Snowbasin grew, and after a large investment in lifts and snowmaking by owner Earl Holding, Snowbasin hosted the 2002 Winter Olympic alpine skiing races for downhill, combined, and super-G, and is expected to reprise these roles for the 2034 Winter Olympics. The movie Frozen was filmed there in 2009.

Snowbasin was ranked as the No. 1 ski resort in the U.S. by SKI Magazine [2], Outside [3] and USA Today [4] in 2025. Snowbasin is located on Mount Ogden at the west end of State Route 226, which is connected to I-84 and SR-39 via SR-167 (New Trappers Loop Road).

History

[edit]Snowbasin is one of the oldest continuously operating ski areas in the United States.[5] Following the end of World War I and the Great Depression numerous, small ski resorts were developed in Utah's snow-packed mountains, and Weber County wanted one of their own. They decided to redevelop the area in and around Wheeler Basin, a deteriorated watershed area that had been overgrazed and subjected to aggressive timber-harvesting.[6]

Lands were restored and turned over to the U.S. Forest Service, and by 1938 the USFS and Alf Engen had committed to turning the area into a recreational site. The first ski tow was built in 1939 and in service at the new Snow Basin ski park.[6] In 1940, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) crew built the first access road to the new resort, allowing easy access for the general public.[5]

In the 1950s, Sam Huntington of Berthoud Pass, Colorado, purchased Snow Basin from the City of Ogden and proceeded to expand the uphill capacity beyond the Wildcat single-seat wooden tower lift and the old rope tow. Overall, he installed a twin chair in place of the rope tow, and a platter-pull tow, later replaced by a twin chair, was installed at Porcupine, to the left of the steep rocky face of Mount Ogden.[7]

The fourth NCAA Skiing Championships, the first in Utah, were held at Snow Basin in 1957.[8][9] The downhill race course was set on the right side of the steep face of Mt. Ogden, on the slope named "John Paul Jones", after an early Snow Basin skier. The John Paul Jones' run was only accessible with a 45-minute hike from the top of the Porcupine lift.[7]

Anderl Molterer, of the Austrian national ski team competing there that weekend, approached Huntington and told him if a lift was built directly to the top of the John Paul Jones run, he would bring his world famous Austrian team to Snow Basin to train on it. Molterer said John Paul was the best downhill run in the world. Huntington ignored this proposal, and a lift to the top of John Paul would not be built until Snowbasin received the rights to hold the alpine speed events for the 2002 Winter Olympics.

Huntington was killed five years later in 1962, as he was performing post-season maintenance, replacing an electrical fuse at the Porcupine lift.[7][10] Several Ogden businessmen purchased Snow Basin from the Huntington family.

Another major personality to come out of Snow Basin was M. Earl Miller, who ran the ski school from the mid-1950s until 1987. Miller played a key role in drafting the Professional Ski Instructors of America (PSIA) American Ski Technique in 1961.

Pete Seibert, founder of Vail, led a partnership which bought Snow Basin in 1978,[11][12] but ran into financial difficulty in 1984. The area was sold that October to Earl Holding, owner of Sun Valley in Idaho, and it became "Snowbasin".[13][14][15][16]

2002 Winter Olympics & Paralympics

[edit]Because it was to serve as an Olympic venue site, the U.S. Congress passed the Snowbasin Land Exchange Act in 1996 as part of the Omnibus Lands Bill.[17] The act transferred 1,377 acres (5.57 km2) of National Forest System lands near the resort to the private ownership of Snowbasin, and identified a set of projects that were necessary for the resort to host the Olympic events.[5] Six years earlier in 1990, a similar swap had been denied by the U.S. Forest Service.[18] These projects allowed Snowbasin to double in size in 1998 with new terrain expansions onto Allen Peak to the north and Strawberry and DeMoisy Peaks to the south.

During the 2002 Olympics, Snowbasin hosted the downhill, combined (downhill and slalom), and super-G events. The spectator viewing areas consisted of a stadium at the foot of the run, with two sections of snow terraces for standing along both sides of the run.[19] The spectator capacity was 22,500 per event; 99.1 percent of tickets were sold, and 124,373 spectators were able to view events at the Snowbasin Olympic venue.[20] During the 2002 Winter Paralympics, Snowbasin hosted the Alpine Skiing events, including downhill, super-G, slalom, and giant slalom.[21]

Statistics

[edit]Mountain information

[edit]

at the 2002 Winter Olympics

- Top elevation: 9,350 feet (2,850 m)[22]

- Base elevation: 6,391 feet (1,948 m)[22]

- Vertical rise: 2,959 feet (902 m)[22]

- Average yearly snowfall: 350 inches (890 cm)[22]

- Skiable area: 3,000 acres (12.1 km2)[23]

- Snowmaking area: 600 acres (240 ha)[23]

Trails

[edit]

- Total runs: 104

- Run ratings: 7 easier, 30 more difficult, 35 most difficult, 32 expert only

- Total Nordic trails: 5, approximately 16 miles (26 km)

- Nordic trail ratings: 3 easier, 1 more difficult, 1 most difficult

- Terrain parks: 3

- Terrain park ratings: The Crazy Kat (easier), Coyote (Intermediate), and Apex (Advanced) parks.

- Superpipe: none

Lifts

[edit]- Total lifts: 13[22]

- Chairlifts: 9

- 1 15-Person Tram

- Allen Peak Tram (Doppelmayr, 1998)

- 2 Gondolas

- Strawberry Express (Doppelmayr, 1998)

- Needles Express (Doppelmayr, 1998)

- 3 high speed six packs

- Wildcat Express (Doppelmayr, 2017)

- Middle Bowl Express (Leitner-Poma, 2021)

- DeMoisy Express (Leitner-Poma, 2023)

- 3 high speed quads

- John Paul Express (Doppelmayr, 1998)

- Little Cat Express (Doppelmayr-CTEC, 2008)

- Becker Express (Leitner-Poma, 2025)

- 1 triple chairlift

- Porcupine (Albertsson-Stadeli, 1985)

- 1 15-Person Tram

- Surface lifts: 3

- 2 Magic carpet

- 1 Hand rope surface tow (tubing hill)

- Chairlifts: 9

Death

[edit]- 1 male skier collided with a weather station on February 11, 2022.

- Paramedics intended live saving measures on the unresponsive victim.

- Skier was pronounced dead on the scene.

Winter season

[edit]- Ski season dates: late-November to mid-April (conditions permitting)

- Operating hours: Gondola: 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. daily (some lifts close at 3:30 p.m. daily)

Grizzly Center retail and rentals: 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

Summer season

[edit]- Summer season dates: Father's Day Weekend in June to First Weekend in October (conditions permitting)

- Operating hours: 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday, Sunday and holidays

- Total trails: 17, approximately 25 miles (40 km)

- Trail ratings: 4.5 easy, 6.5 moderate, 3 difficult, 3 hike only

References

[edit]- ^ a b Grass, Ray (March 11, 1982). "SnowBasin". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). p. D3.

- ^ "Best Ski Resorts in the United States: 2025 Resort Guide". Ski Magazine. October 20, 2025.

- ^ "Your Guide to the Top 11 Ski Resorts in the U.S. and Canada". Outside Magazine. November 18, 2024.

- ^ "USA TODAY Names Snowbasin Resort No. 1 in US and Canada". Snowbasin Resort Blog. November 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c Snowbasin Resort Company (2010). "Our History". Snowbasin Resort website. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ a b State of Utah. "History of Snowbasin". Utah History to Go. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ a b c Kadleck, Dave (March 5, 1966). "Snow Basin "natural" for Olympic ski site". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). p. A5.

- ^ Aldous, Kay (April 1, 1957). "Same pattern: Denver atop NCAA ski standings". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). p. B3.

- ^ "Denver nabs crown in NCAA ski meet". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. April 1, 1957. p. 10.

- ^ "Ski lift owner electrocuted at Snow Basin". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). April 24, 1962. p. B2.

- ^ "Vail founder buys resort". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). Associated Press. October 21, 1978. p. 13.

- ^ Knudson, Max B. (March 20, 1981). "Snow Basin hopes Trapper's Loop will let cat out of bag". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). p. D11.

- ^ Sevack, Maxine (April 1985). "Big Mountains: Snowbasin". SKI. p. 26.

- ^ "Sun Valley Co. buys Snow Basin resort". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). October 11, 1984. p. 2B.

- ^ Grass, Dan (January 24, 1985). "Snowbasin is finally headed in right direction". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). p. D3.

- ^ Grass, Dan (September 11, 1986). "Snowbasin". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). p. D3.

- ^ "Snowbasin swap gets green light". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). Associated Press. November 12, 1996. p. A1.

- ^ Grass, Ray (February 8, 1990). "Forest Service turns down swap, so Snowbasin halts resort plans". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). p. D2.

- ^ Salt Lake Organizing Committee (2001). Official Spectator Guide. p. 64.

- ^ Salt Lake Organizing Committee (2002). Official Report of the XIX Olympic Winter Games (PDF). p. 75. ISBN 0-9717961-0-6. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ Salt Lake Organizing Committee (2001). Official Spectator Guide. p. 186.

- ^ a b c d e Ski Utah (2010). "Snowbasin, A Sun Valley Resort". Ski Utah website. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Snowbasin Resort Company (2010). "Press Kit: Facts". Snowbasin Resort website. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Ski Utah - Resort Profile

- First Tracks online magazine - Article on Snowbasin's 2002 improvements

- Future Plans as of 2014 - 2014 Article about expansion and upgrades to Snowbasin

Snowbasin

View on GrokipediaSnowbasin Resort is an alpine ski area in Huntsville, Utah, established in 1940 as one of the oldest continuously operating ski resorts in North America.[1] Located approximately 40 minutes northeast of Salt Lake City International Airport in Weber County, it offers 3,000 acres of skiable terrain across three peaks—Strawberry, Needles, and John Paul—with a base elevation of 6,450 feet, a summit elevation of 9,465 feet, and a vertical drop of 3,000 feet.[2][3] The resort features 13 lifts serving 115 trails and receives an average annual snowfall of 325 inches, supporting a range of skiing from beginner slopes to expert bowls and Olympic-caliber downhill courses such as Grizzly and Wildflower.[2] Snowbasin gained international prominence by hosting the men's and women's downhill, super-G, and combined alpine skiing events at the 2002 Winter Olympics, where significant infrastructure upgrades, including high-speed lifts and expanded runs, were implemented to meet competition standards.[1] These enhancements, combined with its uncrowded slopes and varied terrain, have earned it accolades such as No. 1 ranking in SKI Magazine's annual reader's resort guide.[4] Beyond winter sports, the resort supports year-round activities like hiking and biking, emphasizing its role as a world-class, independently owned destination focused on natural beauty and accessibility.[2]

Geography and Location

Terrain and Climate

Snowbasin Resort is situated in the Wasatch Range of the Rocky Mountains, approximately 40 miles northeast of Ogden, Utah, within Weber County. The resort's base elevation stands at 6,450 feet (1,965 meters), while the summit reaches 9,465 feet (2,886 meters) at the top of Mount Allen, providing a vertical drop exceeding 3,000 feet (914 meters). This substantial elevation range contributes to diverse skiing conditions, from beginner-friendly lower slopes to advanced terrain at higher altitudes.[2][5] The climate at Snowbasin features a cold, snowy winter season typical of the northern Wasatch front, with average annual snowfall of 325 inches (826 centimeters). Precipitation is enhanced by lake-effect snow originating from the nearby Great Salt Lake, which warms prevailing westerly winds and increases moisture content before storms interact with the mountain barrier, though Pacific frontal systems remain the primary snow source. Historical data from regional weather stations indicate reliable snow cover from December through April, supporting extended ski seasons.[2][6] Terrain at Snowbasin encompasses over 3,000 acres of varied slopes, including north- and northeast-facing aspects that preserve powder snow by minimizing solar exposure and wind scouring. These orientations, combined with open bowls, gladed runs, and steep chutes, offer conditions favorable for deep snow retention and diverse snow types, from dry powder to groomed cruisers, influenced by the mountain's topographic exposure to prevailing storm tracks.[5][7]

History

Early Development and Naming

In the late 1930s, amid a surge in skiing interest following the Great Depression, local officials in Ogden, Utah, identified Wheeler Basin—located in the Wasatch Range—as a promising site for a new recreational ski area, building on early efforts to restore the Wheeler Creek watershed and expand public access to winter sports in Weber County.[8][9] This development aligned with the grassroots emergence of small ski resorts across Utah's mountains, where communities installed basic rope tows to capitalize on abundant snowfall and promote outdoor recreation.[8] To establish an identity for the undeveloped basin east of Ogden, the Ogden Chamber of Commerce sponsored a naming contest in 1939, which drew entries envisioning its potential as a natural snow repository for water supply and skiing. Geneve Woods won with her submission "Snow Basin," reflecting the area's topographic basin shape filled with powder snow that would melt into pure drinking water—a name that encapsulated its hydrological and recreational promise.[10][11] The first rope tow became operational on Becker Hill that same year, with formal opening proclaimed by the mayor on November 27, 1940, marking Snowbasin's entry as one of Utah's pioneering ski venues under initial city management.[12] World War II delayed further infrastructure, but post-war advancements included the installation of Snowbasin's first chairlift in 1946, alongside the establishment of a ski school and dedication ceremonies, solidifying its status as one of the oldest continuously operating ski areas in the United States.[8][13] These early facilities—rope tows, basic trails, and minimal lodges—catered to local skiers and laid the foundation for gradual expansion in the 1950s, prior to private ownership transitions.[14]Ownership Changes and Pre-Olympics Era

Throughout the 1970s, Snowbasin—then known as Snow Basin—experienced frequent ownership transitions amid efforts to stabilize operations as a modest ski area.[10] These changes reflected challenges in attracting consistent investment for a resort reliant on natural snowfall and basic infrastructure in remote Weber County.[11] In 1978, a partnership led by Peter Seibert, founder of Vail Resorts, acquired the property and formalized the name as "Snowbasin," dropping the space to streamline branding under new private proprietorship.[10] This era emphasized incremental enhancements, such as the construction of the Glendale Inn Lodge, replacement of a ropetow with the Porcupine chairlift, and completion of the Wildcat double chairlift in the early 1970s, all funded through owner capital without significant public support.[10] By 1979, following the name standardization, Snowbasin added the Middle Bowl triple chairlift and expanded its day lodge by 2,700 square feet, boosting capacity for local day-trippers and extending accessible terrain modestly.[10] However, Seibert's group encountered financial strain by 1984, leading to the sale of the resort that October to Earl Holding, an oil executive and owner of Sun Valley Resort in Idaho, via his Sun Valley Company.[11] Holding's acquisition marked a shift toward sustained private stewardship, with initial focus on operational viability rather than aggressive expansion; for over a decade, investments remained conservative, prioritizing maintenance amid annual losses and a skier base drawn largely from nearby Ogden and Salt Lake City communities.[15] In the late 1980s and 1990s, Holding revised the resort's master development plan in 1985 to envision year-round use, incorporating private funds for access improvements like the Trappers Loop road segment completed between 1989 and 1991, which eased travel from the Salt Lake City airport without relying on major subsidies.[10] Lift upgrades addressed aging infrastructure—decommissioning the Wildcat double in 1985, Porcupine double in 1986, and Becker double in 1987—while trail grooming and snowmaking enhancements supported steady, self-financed growth in skiable acres, catering to a niche of intermediate and advanced local skiers with minimal national marketing.[16] This period preserved Snowbasin's character as an under-the-radar destination, avoiding debt-fueled overdevelopment until external opportunities arose.[17]2002 Winter Olympics Preparation and Hosting

Snowbasin Resort was selected as the venue for the men's and women's downhill, super-G, and combined alpine skiing events at the 2002 Winter Olympics due to its steep terrain and expansive base area capable of accommodating large-scale operations.[18] Preparations began in the late 1990s under owner Earl Holding, involving significant upgrades to meet International Ski Federation (FIS) standards, including the construction of new race courses designed by Olympic course architect Bernhard Russi.[19] The Grizzly Downhill course for men measured 9,895 feet in length with a 2,897-foot vertical drop and a steepest pitch of 74 degrees, while the Wildflower course served the women's events; both were completed by late 1999.[20] Additional infrastructure included new high-speed lifts such as the John Paul gondola, expanded snowmaking systems among the world's most advanced at the time, and the mid-mountain John Paul Lodge for athlete support.[21][22] The Olympic competitions commenced on February 10, 2002, with the men's downhill on the Grizzly course, where Fritz Strobl of Austria won gold in a time of 1:39.13, achieving speeds up to 80 mph on sections of the run.[23][24] Subsequent events included the super-G on February 16, won by Kjetil André Aamodt of Norway in 1:21.48, and the combined downhill on February 13, with events proceeding without major safety incidents or race delays due to course conditions.[25] A 25,000-seat spectator stadium was erected at the finish area to facilitate viewing.[10] Overall, the venue hosted five alpine events successfully, contributing to the Games' alpine skiing program alongside slalom and giant slalom at other Utah resorts, with official results documenting 55 competitors from 22 nations in the men's downhill alone.[26] The preparations ensured compliance with FIS technical requirements, enabling high-performance racing metrics reflective of the courses' demanding profiles.[27]Post-Olympics Expansions and Modernization

Following the 2002 Winter Olympics, Snowbasin Resort has maintained a program of private capital investments in infrastructure upgrades, emphasizing lift modernizations, terrain access improvements, snowmaking enhancements, and base area expansions to sustain operational capacity and visitor experience amid growing demand.[28] These efforts, funded under family ownership, have incrementally increased lift-served terrain and uphill transport efficiency without relying on public subsidies.[29] Key lift developments include the addition of the Wildcat Handle Tow in 2020 for beginner areas, the Middle Bowl Express in 2021 to access intermediate bowls, and the DeMoisy Express in 2023, which opened additional gladed terrain on DeMoisy Peak.[28] In August 2024, the resort announced the full replacement of the Becker Chairlift—installed as a fixed-grip triple in 1986—with a high-speed detachable quad ahead of the 2025-26 season; the new lift covers over 5,800 linear feet with a 1,300-foot vertical ascent, doubling capacity to 1,800 skiers per hour and shortening ride times to six minutes while serving varied intermediate and beginner runs.[29] This marks the fourth such lift project in six years, directly expanding usable terrain.[28] Snowmaking coverage has been broadened across the resort's 3,000 acres since 2002 to mitigate seasonal variability, enabling earlier openings and consistent base conditions through automated systems and energy-efficient nozzles, though exact acreage metrics remain proprietary.[28] Terrain modifications tied to these lifts, such as the 2025 widening of Family Zone trails including Bear Hollow, Snowshoe, and Slow Road, prioritize improved sightlines, grooming flow, and safety for novice skiers.[29] Base facilities have seen parallel upgrades, including expanded parking lots, doubled shuttle bus services, and a revised 2024 traffic pattern via Trapper’s Loop entry that accelerated vehicle ingress by 25 percent; dining venues have multiplied with added mid-mountain options like the reconstructed John’s Café.[29] Operational modernizations for 2025-26 further include RFID-enabled ticketing and pass gates for streamlined access, alongside refurbished cabins on the John’s Gondola to enhance reliability.[28]Ownership and Management

Earl Holding Era and Family Ownership

In 1984, Robert Earl Holding and his wife Carol acquired Snowbasin Resort through their Sun Valley Company, which had purchased the flagship Sun Valley Resort in Idaho seven years earlier.[30][11] This acquisition linked Snowbasin to a portfolio of luxury properties, including high-end hotels under the Little America and Grand America brands, reflecting Holding's strategy of investing in premium, experience-focused assets rather than mass-market operations.[31] As owner of Sinclair Oil Corporation, Holding applied a private-enterprise model emphasizing long-term capital improvements over short-term revenue maximization, enabling substantial infrastructure upgrades at Snowbasin without the constraints of public markets or external investors.[32] Following Earl Holding's death on April 19, 2013, at age 86, the family maintained full control of Snowbasin, with spokesperson Jack Sibbach confirming that "the resort is and will continue to be owned by the Holding family."[33] This continuity avoided sales or public listings, preserving decision-making autonomy for multi-decade planning horizons. In 2021, the Holdings divested Sinclair Oil assets but retained the ski resorts and associated hospitality ventures, underscoring a deliberate focus on leisure properties.[34] Even after Carol Holding's passing on December 22, 2024, family representatives affirmed "zero plans" to sell, prioritizing sustained private stewardship over liquidity events.[35] Under Holding family ownership, Snowbasin cultivated an ethos of exclusivity through controlled access policies, such as historically limiting season pass availability to manage skier density and enhance on-mountain quality—decisions rooted in observed correlations between lower visitor volumes and superior terrain preservation.[36] This approach, distinct from volume-driven models at corporate resorts, supported investments in uncrowded skiing experiences, aligning with empirical patterns of reduced lift lines and better snow grooming at lower-density operations.[37] The family's reticence toward multi-resort alliances until partnerships like the Ikon Pass in recent years further reinforced this vision of independent, high-caliber operation.[38]Operational Philosophy and Investments

Snowbasin's management philosophy centers on delivering a premium, low-volume skiing experience that prioritizes terrain quality, minimal crowds, and luxurious guest amenities over maximizing visitor throughput, setting it apart from mass-market competitors. This strategy, continued under family ownership since Earl Holding's acquisition in 1984, focuses on controlled capacity to preserve slope density and enhance enjoyment for affluent, discerning skiers willing to pay higher ticket prices without reliance on multi-resort passes.[39][40] The approach yields consistently low crowd levels, as evidenced by guest reports of crowd-free conditions even during peak periods.[41] Post-2002 Olympics, the resort has funded infrastructure upgrades through private capital from operations and family resources, eschewing taxpayer support that characterized Olympic-era developments. Key recent investments include a high-speed six-person chairlift (DeMoisy Express), refurbished gondola cabins, expanded parking for improved traffic flow, and additions like 22 new snowmaking machines in prior seasons, all announced in resort updates from 2022 to 2024.[29][42] These expenditures enhance operational efficiency and accessibility while upholding free parking without reservations, reinforcing self-sustaining business realism.[43] Operational decisions are informed by data analytics, including targeted marketing to high-end demographics via campaigns like "Go North" and "No. 1," which have driven record visitation and earned awards from Utah Business and NSAA finalists in 2024-2025. This has correlated with elevated consumer satisfaction, including rising net promoter scores reported by marketing director Michael Rueckert, and top placements in reader surveys such as SKI Magazine's No. 1 North American resort for 2025 and USA TODAY's best ski resort.[44][45][46]Facilities and Infrastructure

Mountain Statistics and Vertical Drop

Snowbasin Resort encompasses 3,000 acres of lift-served skiable terrain, providing expansive access for skiers and snowboarders across its north- and south-facing aspects.[2] The resort's vertical drop measures 3,000 feet, calculated from a base elevation of 6,450 feet at the primary Grizzly base area to a top lift-served elevation of 9,465 feet near the Needles Gondola summit.[2] [5] This lift-served vertical ranks as the second-highest in Utah, surpassing many regional peers like Alta's 2,020 feet while trailing Snowbird's 3,240 feet, enabling long, continuous descents that emphasize the mountain's scale for advanced and intermediate terrain exploration.[5] [47]| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Skiable Acres | 3,000 |

| Vertical Drop | 3,000 feet |

| Base Elevation | 6,450 feet |

| Summit Elevation | 9,465 feet |