Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Spacetime topology

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Spacetime |

|---|

|

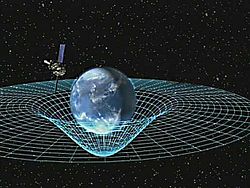

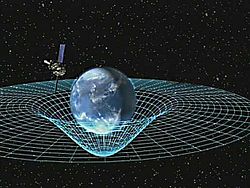

Spacetime topology is the topological structure of spacetime, a topic studied primarily in general relativity. This physical theory models gravitation as the curvature of a four dimensional Lorentzian manifold (a spacetime) and the concepts of topology thus become important in analysing local as well as global aspects of spacetime. The study of spacetime topology is especially important in physical cosmology.

Types of topology

[edit]There are two main types of topology for a spacetime M.

Manifold topology

[edit]As with any manifold, a spacetime possesses a natural manifold topology. Here the open sets are the image of open sets in .

Path or Zeeman topology

[edit]Definition:[1] The topology in which a subset is open if for every timelike curve there is a set in the manifold topology such that .

It is the finest topology which induces the same topology as does on timelike curves.[2]

Properties

[edit]Strictly finer than the manifold topology. It is therefore Hausdorff, separable but not locally compact.

A base for the topology is sets of the form for some point and some convex normal neighbourhood .

( denote the chronological past and future).

Alexandrov topology

[edit]The Alexandrov topology on spacetime, is the coarsest topology such that both and are open for all subsets .

Here the base of open sets for the topology are sets of the form for some points .

This topology coincides with the manifold topology if and only if the manifold is strongly causal but it is coarser in general.[3]

Note that in mathematics, an Alexandrov topology on a partial order is usually taken to be the coarsest topology in which only the upper sets are required to be open. This topology goes back to Pavel Alexandrov.

Nowadays, the correct mathematical term for the Alexandrov topology on spacetime (which goes back to Alexandr D. Alexandrov) would be the interval topology, but when Kronheimer and Penrose introduced the term this difference in nomenclature was not as clear[citation needed], and in physics the term Alexandrov topology remains in use.

Planar spacetime

[edit]Events connected by light have zero separation. The plenum of spacetime in the plane is split into four quadrants, each of which has the topology of R2. The dividing lines are the trajectory of inbound and outbound photons at (0,0). The planar-cosmology topological segmentation is the future F, the past P, space left L, and space right D. The homeomorphism of F with R2 amounts to polar decomposition of split-complex numbers:

- so that

- is the split-complex logarithm and the required homeomorphism F → R2, Note that b is the rapidity parameter for relative motion in F.

F is in bijective correspondence with each of P, L, and D under the mappings z → –z, z → jz, and z → – j z, so each acquires the same topology. The union U = F ∪ P ∪ L ∪ D then has a topology nearly covering the plane, leaving out only the null cone on (0,0). Hyperbolic rotation of the plane does not mingle the quadrants, in fact, each one is an invariant set under the unit hyperbola group.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Luca Bombelli website Archived 2010-06-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ *Zeeman, E.C. (1967). "The topology of Minkowski space". Topology. 6 (2): 161–170. doi:10.1016/0040-9383(67)90033-X.

- ^ Penrose, Roger (1972), Techniques of Differential Topology in Relativity, CBMS-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics, p. 34

References

[edit]- Zeeman, E. C. (1964). "Causality Implies the Lorentz Group". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 5 (4): 490–493. Bibcode:1964JMP.....5..490Z. doi:10.1063/1.1704140.

- Hawking, S. W.; King, A. R.; McCarthy, P. J. (1976). "A new topology for curved space–time which incorporates the causal, differential, and conformal structures" (PDF). Journal of Mathematical Physics. 17 (2): 174–181. Bibcode:1976JMP....17..174H. doi:10.1063/1.522874.