Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

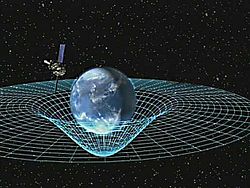

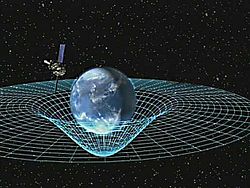

Curved space

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Spacetime |

|---|

|

Curved space often refers to a spatial geometry which is not "flat", where a flat space has zero curvature, as described by Euclidean geometry.[1] Curved spaces can generally be described by Riemannian geometry, though some simple cases can be described in other ways. Curved spaces play an essential role in general relativity, where gravity is often visualized as curved spacetime.[2] The Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric is a curved metric which forms the current foundation for the description of the expansion of the universe and the shape of the universe.[citation needed] The fact that photons have no mass yet are distorted by gravity, means that the explanation would have to be something besides photonic mass. Hence, the belief that large bodies curve space and so light, traveling on the curved space will, appear as being subject to gravity. It is not, but it is subject to the curvature of space.

Simple two-dimensional example

[edit]A very familiar example of a curved space is the surface of a sphere. While to our familiar outlook the sphere looks three-dimensional, if an object is constrained to lie on the surface, it only has two dimensions that it can move in. The surface of a sphere can be completely described by two dimensions, since no matter how rough the surface may appear to be, it is still only a surface, which is the two-dimensional outside border of a volume. Even the surface of the Earth, which is fractal in complexity, is still only a two-dimensional boundary along the outside of a volume.[3]

Embedding

[edit]

One of the defining characteristics of a curved space is its departure from the Pythagorean theorem.[citation needed] In a curved space

- .

The Pythagorean relationship can often be restored by describing the space with an extra dimension. Suppose we have a three-dimensional non-Euclidean space with coordinates . Because it is not flat

- .

But if we now describe the three-dimensional space with four dimensions () we can choose coordinates such that

- .

Note that the coordinate is not the same as the coordinate .

For the choice of the 4D coordinates to be valid descriptors of the original 3D space it must have the same number of degrees of freedom. Since four coordinates have four degrees of freedom it must have a constraint placed on it. We can choose a constraint such that Pythagorean theorem holds in the new 4D space. That is

- .

The constant can be positive or negative. For convenience we can choose the constant to be

- where now is positive and .

We can now use this constraint to eliminate the artificial fourth coordinate . The differential of the constraining equation is

- leading to .

Plugging into the original equation gives

- .

This form is usually not particularly appealing and so a coordinate transform is often applied: , , . With this coordinate transformation

- .

Without embedding

[edit]The geometry of a n-dimensional space can also be described with Riemannian geometry. An isotropic and homogeneous space can be described by the metric:

- .

This reduces to Euclidean space when . But a space can be said to be "flat" when the Weyl tensor has all zero components. In three dimensions this condition is met when the Ricci tensor () is equal to the metric times the Ricci scalar (, not to be confused with the R of the previous section). That is . Calculation of these components from the metric gives that

- where .

This gives the metric:

- .

where can be zero, positive, or negative and is not limited to ±1.

Open, flat, closed

[edit]An isotropic and homogeneous space can be described by the metric:[citation needed]

- .

In the limit that the constant of curvature () becomes infinitely large, a flat, Euclidean space is returned. It is essentially the same as setting to zero. If is not zero the space is not Euclidean. When the space is said to be closed or elliptic. When the space is said to be open or hyperbolic.

Triangles which lie on the surface of an open space will have a sum of angles which is less than 180°. Triangles which lie on the surface of a closed space will have a sum of angles which is greater than 180°. The volume, however, is not .

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. II Ch. 42: Curved Space". www.feynmanlectures.caltech.edu. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

- ^ "Curved Space". www.math.brown.edu. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

- ^ "Curved Space - Special and General Relativity - The Physics of the Universe". www.physicsoftheuniverse.com. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

Further reading

[edit]- The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. II Ch. 42: Curved Space

- Papastavridis, John G. (1999). "General n-Dimensional (Riemannian) Surfaces". Tensor Calculus and Analytical Dynamics. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 211–218. ISBN 0-8493-8514-8.

External links

[edit]- Curved Spaces, simulator for multi-connected universes developed by Jeffrey Weeks