Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Spinal board

View on Wikipedia| Spinal board | |

|---|---|

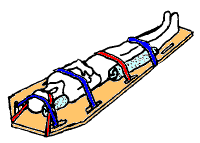

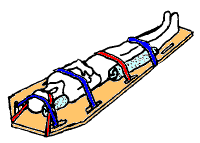

Spinal motion restriction with a long spine board | |

| Other names | |

A spinal board,[4] is a patient handling device used primarily in pre-hospital trauma care. It is designed to provide rigid support during movement of a person with suspected spinal or limb injuries.[5] They are most commonly used by ambulance staff, as well as lifeguards and ski patrollers.[2][6] Historically, backboards were also used in an attempt to "improve the posture" of young people, especially girls.[7]

Due to lack of evidence to support long-term use, the practice of keeping people on long boards for prolonged periods of time is decreasing.[8][9]

Extrication uses

[edit]The spinal backboard was originally designed as a device to remove people from a vehicle. After a time people were simply kept on the spine board for transport without evidence supporting this need.[5][10]

Medical uses

[edit]A spinal board is primarily indicated for judicious use to transport people who may have had a spinal injury, usually due to the mechanism of injury, and the attending team are not able to rule out a spinal injury.[11] The person should be transferred from the board to a hospital bed as soon as possible.[11] For comfort and safety reasons, it is recommended to transfer the person to a vacuum mattress instead, in which case a scoop stretcher or long spine board is just used for the transfer.[12]

Despite its history of use, there is no evidence that backboards immobilize the spine, nor do they improve the person's outcomes. Additionally, cervical spine motion restriction has been shown to increase mortality in people with penetrating trauma and can cause pain, agitation, respiratory compromise, and can lead to the development of bedsores.[11][13]

Adverse effects

[edit]Common clinical issues found with spinal boards include pressure sore development, inadequacy of spinal motion restriction, pain and discomfort, respiratory compromise and effects on the quality of radiological imaging.[4] For this reason, some professionals view them as unsuitable for the task, preferring alternatives.[14]

It is advised that no patient should spend more than 30 minutes on a spine board, due to the development of discomfort and pressure sores.[5]

Backboards were invented to be a "highly polished surface" to move a person to an EMS bed, not to be used as spinal securing device.[citation needed]

Construction

[edit]

Backboards are almost always used in conjunction with the following devices:[citation needed]

- a cervical collar with occipital padding as needed;

- side head supports, such as a rolled blanket or head blocks (head immobilizer) made specifically for this purpose, used to avoid the lateral rotation of the head;

- straps to secure the patient to the long spine board, and tape to secure the head

Spine boards are typically made of wood or plastic, although there has been a strong shift away from wood boards due to their higher level of maintenance required to keep them in operable condition and to protect them from cracks and other imperfections that could harbor bacteria.

Backboards are designed to be slightly wider and longer than the average human body to accommodate the immobilization straps, and have handles for carrying the patient. Most backboards are designed to be completely X-ray translucent so that they do not interfere with the exam while patients are strapped to them. They are light enough to be easily carried by one person, and are usually buoyant.

Alternatives

[edit]The vacuum mattress may reduce sacral pressures compared to backboards.[15] The conforming nature of the vacuum mattress means that people can be kept immobilized on it for longer periods of time and the immobilisation offers superior stability and comfort.[16] The Kendrick extrication device is another alternative.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ "Online training manual for Neann Long Spine Board". Neann.

- ^ a b Whatling, Shaun. Beach Lifeguarding. Royal Life Saving Society.

- ^ Sen, Ayan (2005). "Spinal Immobilisation in Prehospital Trauma Patient". Journal of Emergency Primary Health Care. 3 (3). ISSN 1447-4999.

- ^ a b Vickery, D. (2001). "The use of the spinal board after the pre-hospital phase of trauma management". Emergency Medicine Journal. 18 (1): 51–54. doi:10.1136/emj.18.1.51. PMC 1725508. PMID 11310463.

- ^ a b c Ambulance Service Basic Training 3rd Edition. IHCD. 2003.

- ^ "Red Cross Lifeguard Management Guide".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Cf. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, Chapter 3.

- ^ Sundstrøm, Terje; Asbjørnsen, Helge; Habiba, Samer; Sunde, Geir Arne; Wester, Knut (2013-08-20). "Prehospital Use of Cervical Collars in Trauma Patients: A Critical Review". Journal of Neurotrauma. 31 (6): 531–540. doi:10.1089/neu.2013.3094. ISSN 0897-7151. PMC 3949434. PMID 23962031.

- ^ Singletary, Eunice M.; Charlton, Nathan P.; Epstein, Jonathan L.; Ferguson, Jeffrey D.; Jensen, Jan L.; MacPherson, Andrew I.; Pellegrino, Jeffrey L.; Smith, William “Will” R.; Swain, Janel M. (2015-11-03). "Part 15: First Aid". Circulation. 132 (18 suppl 2): S574 – S589. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000269. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 26473003.

- ^ Wesley, Karen. "Weighing the Pros & Cons of Current Spine Immobilization Techniques". JEMS. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ a b c National Association of EMS Physicians and American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. January 15, 2013 Position Statement: EMS Spinal Precautions and the Use of the Long Backboard

- ^ Morrissey, J (Mar 2013). "Spinal immobilization. Time for a change". Journal of Emergency Medical Services. 38 (3): 28–30, 32–6, 38–9. PMID 23717917.

- ^ "The Evidence Against Backboards". EMS World. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Tasker-Lynch, Aidan. "Spinal Boards do NOT work". 18 (1). Emergency Medicine Journal: 51–54.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Maschmann, Christian; Jeppesen, Elisabeth; Rubin, Monika Afzali; Barfod, Charlotte (2019-08-19). "New clinical guidelines on the spinal stabilisation of adult trauma patients - consensus and evidence based". Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 27 (1): 77. doi:10.1186/s13049-019-0655-x. ISSN 1757-7241. PMC 6700785. PMID 31426850.

- ^ Luscombe, MD; Williams, JL (2003). "Comparison of a long spinal board and vacuum mattress for spinal immobilisation". Emergency Medicine Journal. 20 (5): 476–478. doi:10.1136/emj.20.5.476. PMC 1726197. PMID 12954698.

- ^ The trauma handbook of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004. p. 37. ISBN 9780781745963.

Spinal board

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

A spinal board, also known as a long spine board (LSB), backboard, or spineboard, is a rigid, flat patient-handling device used primarily in pre-hospital trauma care to support and immobilize the spine and limbs in cases of suspected injury.[1] It consists of a hard, rectangular surface designed to distribute the patient's weight evenly while restricting movement.[4] Typical dimensions of a spinal board are approximately 72 inches (183 cm) in length, 16 to 18 inches (41 to 46 cm) in width, and 1 to 2 inches (2.5 to 5 cm) in thickness, allowing it to accommodate adult patients while remaining portable for emergency responders.[5] The primary purpose of the device is to maintain neutral spinal alignment during initial handling and transfer, thereby minimizing the risk of secondary injury to the spinal cord in trauma scenarios.[1] Common users of spinal boards include emergency medical services (EMS) personnel for routine trauma response.[1] They are also used by firefighters for rescue operations, lifeguards for water-related incidents, and ski patrollers for slope accidents.[6][7]History

The development of the spinal board in emergency medicine began in the 1960s, amid growing recognition of spinal injuries from motor vehicle accidents and other blunt trauma, prompting the adoption of rigid immobilization devices to prevent secondary neurological damage.[8] Spinal motion restriction practices emerged during this period, with trauma surgeon J.D. "Deke" Farrington recommending backboards for prehospital use in 1968, influencing early EMS textbooks and protocols.[9] By 1971, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons proposed combining a cervical collar with a long spine board as a standard for managing suspected spinal injuries based on mechanism and symptoms.[1] In the 1980s, the spinal board became a standardized tool in emergency medical services through protocols like the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) program, developed in response to a 1976 incident and first introduced in 1980, which incorporated spinal immobilization guidelines emphasizing rigid boards for trauma patients at risk of cervical spine injury.[10] This era saw widespread integration into EMS curricula, such as the 1984 U.S. Department of Transportation EMT standards, shifting from selective application to routine use for many trauma cases.[9] Wooden boards, often plywood with nylon straps introduced around 1979, were common but porous and difficult to clean.[11] The 1990s and 2000s marked a transition to plastic materials for improved hygiene and durability, accelerated by concerns over infections like HIV; rotational molding produced lightweight polyethylene boards with polyurethane foam cores, while manufacturers like Ferno (established 1955) and Laerdal (with spine board patents in 1996 and 1998) drove innovations in design and accessories.[11][12] These advancements made boards more practical for field use, with Ferno offering early folding aluminum models and Laerdal developing adaptable rigid systems.[11] Post-2010, accumulating evidence from systematic reviews questioned the routine use of long spine boards, highlighting risks like pressure ulcers and no proven benefit in reducing spinal cord injury incidence, leading to updated guidelines such as the 2018 joint position statement by NAEMSP and ACS recommending selective application over universal immobilization.[1][13] Studies from 2013 onward supported protocols minimizing board time and favoring alternatives like scoop stretchers for non-critical cases.[14] As of 2025, further innovations, such as the adaptive spine board overlay, aim to mitigate risks like pressure ulcers while maintaining immobilization efficacy.[15]Applications

Extrication

The spinal board plays a critical role in vehicle extrication by providing a rigid platform to immobilize the spine and maintain alignment during the removal of patients from confined or hazardous environments, such as motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) or structural entrapments. This device allows rescuers to secure the patient prior to extraction maneuvers, minimizing secondary injury risk from spinal motion while integrating with tools like hydraulic cutters (e.g., the Jaws of Life) or inflatable airbags to create safe access. In these scenarios, the board facilitates hands-free stabilization, enabling a coordinated team effort to free the patient without compromising spinal integrity.[1][13] The extrication process begins with rapid on-scene assessment to identify patients at risk for spinal injury, based on mechanisms like high-speed impacts or ejections in MVCs, followed by immediate manual inline stabilization of the head and neck by a designated rescuer. A rigid cervical collar is then applied to restrict cervical motion, after which a team of four to five personnel positions themselves around the patient—one at the head, others at the torso, hips, and legs—to prepare for the log-roll maneuver. On a coordinated command, the patient is gently rolled laterally away from the entrapment (e.g., vehicle door), the spinal board is slid underneath, and the patient is rolled back onto the board in a centered position. The patient is secured using multiple straps across the torso, pelvis, and legs, with the head immobilized via lateral blocks or towels and tape across the forehead; in tighter spaces, a Kendrick Extrication Device (KED) may assist before full board application. This sequence ensures minimal flexion, extension, or rotation of the spine throughout removal.[1][13][16] Protocols from the 1970s and 1990s, developed by organizations like the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, emphasized the spinal board's role strictly for short-term extrication to prevent neurological worsening in suspected unstable fractures, rather than prolonged use. Influential studies and guidelines from this era, such as those by Riggins and Kraus (1977), advocated immobilization based on injury mechanism alone, with the board enabling efficient patient transfer from the scene to an ambulance cot. By the 1990s, evidence began highlighting limitations, including inadequate motion restriction in some maneuvers, reinforcing its application as a temporary tool during initial rescue phases only.[17][1]Patient Transport

In pre-hospital emergency medical services (EMS), the spinal board plays a key role in securing patients after extrication for safe transfer to an ambulance, maintaining spinal alignment during movement from the scene to the transport vehicle. Historically, its use became standardized in EMS protocols following the introduction of Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines in the 1980s, which emphasized full spinal immobilization for trauma patients with suspected injuries.[1] Over time, reliance on the spinal board for routine transport has diminished, with current practices limiting its application to high-risk cases where spinal motion restriction is essential, such as in patients with altered mental status or focal neurologic deficits.[13] Securing the patient to the spinal board typically involves a multi-point strapping system, often configured as a 5-point harness that includes straps across the chest, pelvis, and legs to prevent movement while allowing access for vital interventions. The board integrates with ambulance stretchers by being placed directly onto the cot for conveyance, facilitating smooth transfer without log-rolling the patient mid-transport. Upon arrival at the hospital, the immobilized patient is transferred to a gurney using techniques like slider boards or coordinated log-rolls to remove the board promptly.[1] Guidelines emphasize minimizing the duration of spinal board use during transport to reduce potential harm, with recommendations to limit time on the board to under 30 minutes where possible, as tissue interface pressures can lead to complications like sacral hypoxia in healthy individuals after this interval. In practice, EMS teams aim to remove extrication devices like the spinal board once the patient is on the ambulance cot if spinal stability is maintained, or immediately upon hospital arrival.[1][13] Logistically, spinal boards are designed for practicality in EMS operations, with typical weight capacities ranging from 350 to 500 pounds to accommodate most adult patients, and features that ensure compatibility with essential equipment such as defibrillators and intravenous access points during transit.[5] These boards often include multiple handholds for safe handling by EMS crews and are constructed to remain stable under dynamic conditions like ambulance movement.[1]Specialized Uses

In water rescue operations, spinal boards are employed by lifeguards to immobilize and extract victims with suspected spinal injuries from aquatic environments such as pools or oceans. These devices are typically floatable and lightweight to facilitate safe handling in water, allowing for buoyancy support during extrication while maintaining spinal alignment through manual in-line stabilization. Flotation attachments, such as foam-filled or buoyant polyethylene constructions, enable the board to keep the victim afloat, and water-resistant straps are used sparingly to avoid complications like entanglement or delayed rescue, with protocols recommending their application only when essential for secure transport. The International Life Saving Federation (ILSF) integrates spinal boards into its spinal injury management protocols, emphasizing minimal movement and team-based extraction to prevent further harm.[18][19][20] In wilderness and sports settings, spinal boards facilitate remote spinal immobilization and patient transport by teams like ski patrollers or hikers, where access to advanced medical facilities is limited. These applications prioritize portability, with lightweight, compact designs that can be carried in backpacks or toboggans for rapid deployment on slopes, trails, or rugged terrain. The Wilderness Medical Society guidelines endorse the use of rigid backboards for temporary movement in austere environments, focusing on spinal motion restriction rather than prolonged immobilization to minimize risks during evacuation (as of 2024 update). The National Ski Patrol incorporates spinal boards in its outdoor emergency care protocols for sports-related incidents, adapting them for integration with rescue sleds or litters to ensure safe downhill or cross-country transport.[21][22] In mass casualty incidents, spinal boards are used for stabilizing and transporting selected victims with suspected spinal trauma, allowing for efficient movement of high-priority patients to secondary care areas, consistent with selective spinal motion restriction protocols (as of 2025). Specialized variants, such as the MCI spine board, feature multiple handholds and high load capacities (e.g., 600 lbs) for rapid handling in chaotic scenarios. Adaptations for helicopters include secure strapping points compatible with hoist systems, while versions for boats incorporate flotation to maintain stability during water-based evacuations. These tools support protocols from emergency response organizations, enhancing scalability in high-volume events like disasters or multi-vehicle accidents.[23][24][25]Design and Features

Construction Materials

Early spinal boards were constructed from wooden materials, such as plywood, which provided rigid support but were prone to splintering and difficult to disinfect effectively, increasing infection risks from porous surfaces that harbored pathogens.[11][26] This led to their phase-out in favor of more hygienic alternatives, marking a key evolution in material selection for emergency immobilization devices. Contemporary spinal boards are predominantly fabricated from high-density polyethylene (HDPE), a durable thermoplastic known for its impact resistance, lightweight properties (typically 10-15 pounds for standard adult models), and X-ray translucency that allows radiographic imaging without board removal.[27][28] Composite plastics, including carbon fiber-reinforced variants, are also used in premium designs for enhanced rigidity while maintaining low weight and buoyancy for water rescue applications.[29] These materials ensure ease of cleaning and decontamination, critical for repeated use in clinical and prehospital settings.[27] Key design features of these boards prioritize patient safety and handler efficiency, including rounded edges to minimize pressure points and skin abrasions during prolonged contact, multiple integrated handholds (often 12 or more) for secure carrying by teams, and textured non-slip surfaces to prevent patient sliding.[30][27][31] Spinal boards must comply with FDA Class I medical device regulations under general hospital and personal use categories, subjecting them to general controls for safety, labeling, and manufacturing quality without requiring premarket approval.[32] Load-bearing specifications vary by model but typically support patient weights up to 350-1,100 pounds, with static load capacities exceeding 1,000 pounds to ensure structural integrity during extrication and transport.[27][33][34]Accessories

Spinal boards are commonly used in conjunction with cervical collars to provide comprehensive stabilization of the head and neck during suspected spinal injuries. These collars are applied to immobilize the cervical spine, preventing flexion, extension, and rotation, and are typically paired with the board for full spinal motion restriction in prehospital settings. Rigid collars, constructed from stiff foam or plastic materials, are preferred in trauma scenarios for their superior motion restriction capabilities compared to softer variants, which use simpler foam padding and are less effective at limiting movement.[35][36] Head blocks or foam pads serve as essential accessories to restrict lateral and rotational head movement when a patient is secured to the spinal board. These devices, often made from styrofoam or rigid foam, are positioned on either side of the head and secured with tape or straps to the board, enhancing overall cervical immobilization. Disposable versions of head blocks are increasingly utilized to maintain hygiene and reduce cross-contamination risks in emergency medical services (EMS).[1][37] Straps and harnesses are critical for securely fastening the patient to the spinal board, minimizing movement during transport. Common configurations include 3-point or 5-point systems, which anchor the torso, pelvis, and legs using durable nylon webbing equipped with Velcro closures or plastic buckles for quick adjustment and release. These systems effectively limit spinal motion but must be applied carefully to avoid compromising respiratory function.[38][1] Additional accessories enhance the spinal board's practicality and safety. Lifting handles, often padded and integrated or attachable, facilitate safe patient extrication and transport by multiple rescuers. Disposable covers are employed over the board to promote infection control, as studies indicate high contamination rates on reusable equipment, with up to 57% of spinal boards testing positive for blood residues. Spinal boards are also designed for compatibility with the Kendrick Extrication Device (KED), allowing seamless integration during confined-space rescues.[39][40][37]Clinical Aspects

Indications and Guidelines

Spinal boards are indicated for use in prehospital settings when there is suspicion of cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spine injury, particularly in patients with acutely altered mental status (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale score less than 15), evidence of intoxication, midline spinal tenderness or pain, focal neurologic deficits such as numbness or weakness, anatomic spinal deformity, or distracting injuries like long bone fractures or significant burns.[13] These indications align with clinical decision rules such as the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) criteria, which recommend immobilization if any of the following are present: posterior midline cervical spine tenderness, altered mental status, neurologic deficit, or distracting painful injury, and the Canadian C-Spine Rule, which prompts immobilization for high-risk factors including age over 65, dangerous mechanism of injury, or certain clinical findings like extremity paresthesia.[41][42] Additionally, in cases of penetrating trauma accompanied by neurologic deficits, spinal board application may be considered to facilitate extrication and initial stabilization, though routine use is not recommended without such deficits.[43] Contraindications to spinal board use include stable patients without clinical red flags for spine injury, such as those who can be cleared via NEXUS or Canadian C-Spine Rule criteria, and penetrating trauma without associated neurologic deficits, as immobilization in these scenarios has been linked to increased mortality and no mitigation of neurologic harm.[13][44] The 2013 position statement from the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS-COT) and National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP) emphasized selective application, a stance reinforced in subsequent updates. Key guidelines from major organizations advocate for selective and judicious use of spinal boards as part of spinal motion restriction (SMR) protocols. The 2018 joint position statement from ACS-COT, American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), and NAEMSP prioritizes SMR over rigid immobilization, recommending spinal boards primarily for extrication in mechanism-based concerns rather than routine transport, with updates through 2020 maintaining this selective approach to minimize complications.[13] The NAEMSP's 2025 position further limits spinal board use to active extrication only, advising against routine cervical collars or backboards for transport due to lack of proven benefit and potential harm, emphasizing resuscitation and shock management instead.[45] In remote or wilderness settings, the Wilderness Medical Society's 2024 guidelines recommend against rigid spinal boards, favoring vacuum mattresses or nonrigid methods for suspected injuries, with self-extrication encouraged for alert patients and no SMR for penetrating trauma.[21] The American Heart Association's 2025 Basic Life Support guidelines integrate manual SMR for cardiac arrest scenarios involving suspected head or neck trauma, using techniques like jaw thrust to open the airway while minimizing cervical movement, without rigid devices that could impede compressions or ventilation.[46] Protocols for spinal board application begin with manual SMR, involving inline stabilization of the head and neck by trained personnel to maintain neutral alignment before device placement, followed by log-roll maneuvers for board application during extrication.[13] Post-extrication, guidelines stress rapid removal of the spinal board—ideally within 10-15 minutes of hospital arrival or sooner if possible—to avoid pressure-related complications, transitioning to alternative SMR methods like collars or mats only if ongoing restriction is warranted.[45][21]Evidence Base

The evidence base for spinal boards primarily stems from retrospective analyses, biomechanical studies, and systematic reviews, which collectively indicate limited effectiveness in preventing neurological deterioration while highlighting potential risks. A seminal 1998 retrospective study by Hauswald et al. compared outcomes in blunt trauma patients from Malaysia (where routine spinal immobilization was not used) and New Mexico (where it was standard), finding no significant difference in neurological outcomes and suggesting that out-of-hospital immobilization has little or no beneficial effect on preventing injury progression.[47] Similarly, the 2018 Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) practice management guideline, informed by earlier analyses like Haut et al. (2010), concluded that spinal immobilization in penetrating trauma is associated with increased mortality (odds ratio 2.0) without mitigating neurologic injury, based on data from over 45,000 patients showing higher unadjusted mortality rates (14.7% vs. 7.2%) in immobilized cases.[44] Biomechanical studies further demonstrate that spinal boards fail to achieve complete immobilization. A 2016 randomized crossover trial involving healthy volunteers found that the long spine board allowed greater lateral displacement during simulated transport compared to a stretcher mattress alone, with mean movements of up to 2.22 cm at the chest level and 0.97 cm at the head, indicating residual motion that could exacerbate unstable injuries.[48] Overall, meta-analyses and reviews confirm no reduction in neurological injury rates attributable to spinal boards; for instance, the 2001 Cochrane review of prehospital spinal immobilization for trauma patients analyzed available trials and found insufficient high-quality evidence to support routine use, a position unchanged by subsequent updates through 2022 due to the lack of new randomized controlled trials. Recent developments reinforce these findings and advocate for more selective application. The 2023 StatPearls update on EMS long spine board immobilization reviewed international and volunteer studies, noting no difference in spinal cord injury incidence after protocols limited precautions to high-risk cases, and emphasized the absence of level 1 evidence supporting boards for neurologic protection.[1] A 2024 EMOttawa review compared spinal motion restriction (SMR) to traditional immobilization, citing Cochrane analyses (2001–2015) and biomechanical data showing boards increase rather than restrict motion in some scenarios, while a 2025 JournalFeed analysis questioned longstanding dogma by synthesizing evidence that cervical collars and backboards lack therapeutic benefit and may cause net harm.[8][49] In special populations, evidence suggests amplified limitations. For pediatrics, a 2023 PECARN study of over 7,700 cases challenged routine immobilization, finding no increase in disabling spinal injuries after adopting selective SMR protocols, with biomechanical data indicating collars and boards fit poorly and allow excessive motion in children.[50] In the elderly, a 2018 literature review highlighted increased risks of complications without proven neurologic benefits, as age-related spinal degeneration reduces the efficacy of rigid boards, supported by systematic analyses showing higher injury detection rates in non-immobilized groups but no outcome improvements.[51] These findings underscore a shift away from universal use toward evidence-based, patient-specific strategies.Adverse Effects

The use of spinal boards for immobilization can lead to pressure ulcers, particularly in cases of prolonged immobility exceeding 30 minutes, with the risk concentrated over bony prominences such as the sacrum and heels due to sustained interface pressures.[1] Incidence rates have been reported as high as 30.6% in trauma patients subjected to spinal board immobilization, though rates of 10% to 22% are noted in scenarios involving extended transport like intercontinental air evacuations.[1][52] Pain and discomfort are commonly reported among awake patients immobilized on spinal boards, with symptoms including headaches, back pain, and mandibular discomfort emerging as early as 30 minutes of use.[1] Respiratory compromise arises from restricted diaphragmatic and chest wall movement, often exacerbated by securing straps, resulting in reduced forced vital capacity—typically by 17% to 20% of baseline values in healthy volunteers and up to 80% in children.[1][17] Additional complications include an elevated risk of aspiration, stemming from potential impairment of protective airway reflexes during immobilization, as well as challenges in airway access that can complicate intubation efforts.[53] Hypothermia may also occur due to prolonged exposure on the rigid surface, particularly in uncontrolled environments.[54] These risks are amplified in vulnerable populations, such as obese individuals—where uneven pressure distribution over adipose tissue heightens ulcer formation—and the elderly, who exhibit diminished tissue tolerance and respiratory reserve.[55][1] Mitigation strategies include the application of padding to distribute pressure and adherence to time limits on board use, such as those recommended in clinical guidelines to minimize duration beyond initial extrication.[1] Studies from 2015 to 2025 indicate that adverse events associated with spinal boards occur 2 to 5 times more frequently compared to alternative immobilization methods, such as vacuum mattresses, underscoring the need for prompt removal once at a medical facility.[56]Alternatives and Modern Practices

Alternative Devices

Vacuum mattresses, also known as vacuum splints, are flexible immobilization devices consisting of an inflatable mattress filled with polystyrene beads that conform to the patient's body contours once the air is evacuated, providing enhanced spinal stability and patient comfort compared to rigid spinal boards.[58] These devices have been utilized in prehospital care since the 1990s, evolving from earlier vacuum splint technology designed for limb immobilization to full-body spinal support.[59] Studies demonstrate that vacuum mattresses offer superior immobilization by significantly reducing movement in the longitudinal and lateral planes during tilting maneuvers, with one comparison showing they prevent more spinal displacement than long spinal boards under similar conditions. Additionally, they improve patient comfort, lowering the risk of pressure sores due to better pressure distribution over bony prominences.[58] The Kendrick Extrication Device (KED) is a vest-like apparatus designed primarily for extricating patients in seated positions, such as those trapped in vehicles, by securing the torso, pelvis, and head while allowing controlled movement without full log-rolling.[60] Weighing approximately 3.6 kg (8 lb),[61] it is substantially lighter than traditional spinal boards, facilitating easier application in confined spaces and reducing rescuer fatigue during operations. Research indicates that the KED minimizes cervical spine motion during extrication, particularly in non-obese patients, by limiting rotation compared to rapid extrication techniques, though it may increase movement in larger individuals.[60] Scoop stretchers are two-piece aluminum or polymer devices that split longitudinally, enabling rescuers to slide each half under the patient from opposite sides without requiring a full log-roll maneuver, which minimizes spinal disruption during loading.[62] This design enhances efficiency in time-critical scenarios, with studies showing application times comparable to or faster than vacuum mattresses while providing equivalent or superior limitation of spinal motion in destabilized spines relative to manual handling.[63] For instance, the Ferno Scoop EXL model reduces multi-planar movement by 6-8 degrees during placement compared to long backboards, promoting better patient security and comfort.[62] Other alternatives include Ferno's boardless systems, such as the Model 192 vacuum mattress and the FERNO XT Pro half-board for rapid extrication, which prioritize minimal rigid contact to avoid pressure-related complications associated with full spinal boards.[64] Padded mats, often integrated with scoop stretchers or used standalone, further supplement these by offering cushioned support that conforms to the body, reducing interface pressures.[65] Comparative analyses highlight that vacuum-based alternatives like mattresses can reduce involuntary thoracic-lumbar movements more effectively than spinal boards, with some studies reporting significantly less displacement in controlled tests, underscoring their role in modern spinal motion restriction.[66]Shift to Spinal Motion Restriction

Spinal motion restriction (SMR) refers to techniques aimed at maintaining the spine in anatomic alignment and minimizing gross movement, often through manual stabilization or minimal adjuncts like a cervical collar and stretcher, without the routine use of rigid backboards, particularly for low-risk patients with suspected spinal injury.[67][68] The shift toward SMR in emergency medical services (EMS) was driven by the 2013 position statement from the National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP), which recommended against routine use of long backboards due to evidence of associated harms outweighing benefits in most cases. This was reinforced by the 2018 joint position statement from the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS-COT), American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), and NAEMSP, which defined SMR as the preferred approach to limit spinal movement while emphasizing selective application to avoid unnecessary immobilization.[69] Subsequent updates, including the 2025 NAEMSP position on prehospital spinal cord injury management—which emphasizes SMR over traditional immobilization and evaluates device harms/benefits—and the 2024 Wilderness Medical Society guidelines, further promoted SMR protocols that prioritize patient safety by excluding rigid devices unless specifically indicated.[45][21] Implementation of SMR involves prehospital clearance protocols using validated tools such as the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) criteria or the Canadian C-Spine Rule (CCR) to identify low-risk patients who can forgo backboards, allowing manual techniques like hands-on stabilization during extrication and transport.[70][67] EMS training curricula have shifted accordingly, with organizations like the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians incorporating SMR education since 2016 to emphasize evidence-based assessment and selective immobilization.[67] Outcomes of this paradigm shift include reduced complications such as pressure ulcers, respiratory compromise, and pain from prolonged rigid immobilization, as highlighted in the 2024 Wilderness Medical Society guidelines, which strongly recommend nonrigid SMR methods for wilderness and austere environments to enhance overall patient and provider safety.[21][45] Global adoption of SMR has accelerated, with earlier integration in European and Australian EMS protocols compared to the United States, where liability concerns delayed widespread implementation until the mid-2010s.[71][72]References

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36173127/