Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

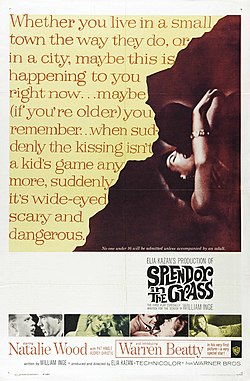

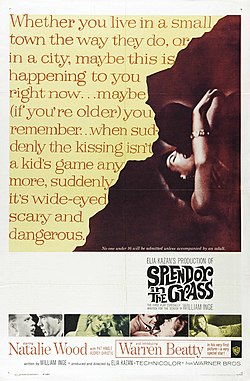

Splendor in the Grass

View on Wikipedia

| Splendor in the Grass | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold | |

| Directed by | Elia Kazan |

| Written by | William Inge |

| Produced by | Elia Kazan |

| Starring | Natalie Wood Warren Beatty Pat Hingle Audrey Christie |

| Cinematography | Boris Kaufman, A.S.C. |

| Edited by | Gene Milford |

| Music by | David Amram |

Production companies | Newtown Productions NBI Company |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $4 million (US / Canada)[1] or $5.5 million[2] |

Splendor in the Grass is a 1961 American period drama film produced and directed by Elia Kazan, from a screenplay written by William Inge. It stars Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty (in his film debut) as two high school sweethearts, navigating feelings of sexual repression, love, and heartbreak. Pat Hingle, Audrey Christie, Barbara Loden, Zohra Lampert, and Joanna Roos are featured in supporting roles.

Splendor in the Grass was released theatrically on October 10, 1961, by Warner Bros. to critical and commercial success. It grossed $4 million, and received two nominations at the 34th Academy Awards for Best Actress (for Wood) and Best Original Screenplay, winning the latter.

Plot

[edit]In 1928 Kansas, teenagers Wilma Dean "Deanie" Loomis and her boyfriend, Bud Stamper, want a more physically intimate relationship, but heed the advice of their parents not to become more involved for the sake of Deanie's reputation and Bud's future plans for college. Bud's sister, Ginny, a flapper, is more worldly, having returned from Chicago after an annulment and rumors of an abortion to the disappointment and shame of her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Ace Stamper. Soon, Bud rescues Ginny from an attempted rape at a New Year's Eve party. Disturbed by what he has seen, he tells Deanie they should stop fooling around, and they break up.

Bud has a liaison with a friend, Juanita. Shortly afterward, Deanie explodes in anger when her mother asks if she is still a virgin. Allen "Toots" Tuttle takes Deanie to a school dance where she sees Bud, and tries to entice him into having sex. Bud rebuffs her and Deanie runs back to Toots, who drives her to a private spot. While there, Deanie realizes that she can't go through with sex, at which point she is almost raped. Escaping from Toots and driven close to madness, she attempts suicide by jumping in the pond, but is rescued just before reaching the waterfalls. Her parents sell their oil stock to pay for her institutionalization, and fortuitously turn a profit prior to the Crash of 1929 that leads to the Great Depression.

While Deanie is in the institution, she meets patient Johnny Masterson, who has anger issues targeted at his parents, who want him to be a surgeon. The two form a bond. Meanwhile, Bud is sent to Yale, where he fails practically all his courses but meets Angelina, the daughter of Italian immigrants who run a local restaurant in New Haven. In October 1929, Bud's father Ace travels to New Haven in an attempt to persuade the dean not to expel Bud from school. Bud tells the dean he only aspires to own a ranch. The stock market crashes while Ace is in New Haven, and he loses almost everything. He takes Bud to New York for a weekend, including to a cabaret nightclub, and has a prostitute sent to Bud's room. Bud rebuffs her. Ace commits suicide by jumping from a building – something he was joking about a short time earlier.

Deanie returns from the asylum after two years and six months, "almost to the day." Ace's widow has gone to live with relatives, and Bud's sister has died in a car crash. Deanie's mother wants to shield her from any potential anguish from meeting Bud, so she pretends to not know where he is. When Deanie's friends from high school come over, her mother gets them to agree to feign ignorance about Bud's whereabouts. However, Deanie's father refuses to coddle his daughter and tells her that Bud has taken up ranching and lives on the old family farm. Her friends drive Deanie to meet Bud at an old farmhouse. He is dressed in plain clothes and married to Angelina; they have an infant son named Bud Jr. and another child on the way. Deanie lets Bud know she is going to marry John (who is now a doctor in Cincinnati). During their brief reunion, Deanie and Bud realize that both must accept what life has thrown at them. Bud says, "What's the point? You gotta take what comes." They each relate that they "don't think about happiness very much anymore."[3]

As Deanie leaves with her friends, Bud only seems partially satisfied by the direction his life has taken. After the others are gone, he reassures Angelina, who has realized that Deanie was once the love of his life.[3] Driving away, Deanie's friends ask her if she is still in love with Bud. She does not answer them, but her voice is heard reciting four lines from Wordsworth's "Intimations of Immortality":

- "Though nothing can bring back the hour

- Of splendor in the grass, glory in the flower

- We will grieve not; rather find

- Strength in what remains behind."

Cast

[edit]- Natalie Wood as Wilma Dean "Deanie" Loomis

- Pat Hingle as Ace Stamper

- Audrey Christie as Frieda Loomis

- Barbara Loden as Virginia "Ginny" Stamper

- Zohra Lampert as Angelina

- Warren Beatty as Bud Stamper

- Fred Stewart as Del Loomis

- Joanna Roos as Mrs. Stamper

- John McGovern as Doc Smiley

- Jan Norris as Juanita Howard

- Martine Bartlett as Miss Metcalf

- Gary Lockwood as Allen "Toots" Tuttle

- Sandy Dennis as Kay

- Crystal Field as Hazel

- Marla Adams as June

- Lynn Loring as Carolyn

- Phyllis Diller as Texas Guinan

- Sean Garrison as Glenn

- Charles Robinson as Johnny Masterson (uncredited)

- Ivor Francis as Dr. Judd (uncredited)

- Peter Romano as Brian Stacy (uncredited)

Production

[edit]

Filmed in New York City at Filmways Studios, Splendor in the Grass is based on people whom screenwriter William Inge knew while growing up in Kansas in the 1920s. He told the story to director Elia Kazan when they were working on a production of Inge's play The Dark at the Top of the Stairs in 1957. They agreed that it would make a good film and that they wanted to work together on it. Inge wrote it first as a novel, then as a screenplay.

The film's title is taken from a line of William Wordsworth's poem "Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood":

- What though the radiance which was once so bright

- Be now for ever taken from my sight,

- Though nothing can bring back the hour

- Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower;

- We will grieve not, rather find

- Strength in what remains behind...

Two years before writing the screenplay for the film, Inge wrote Glory in the Flower (1953), a stage play whose title comes from the same line of the Wordsworth poem. The play relates the story of two middle-aged, former lovers who meet again briefly at a diner after a long estrangement; they are essentially the same characters as Bud and Deanie, though the names are Bus and Jackie.

Scenes of Kansas and the Loomis home were shot in the Travis section of Staten Island, New York City.[4] Exterior scenes of the high school campus were shot at Horace Mann School in the Bronx. The gothic buildings of the North Campus of The City College of New York stand in for Yale University in New Haven.[5] The scenes at the waterfall were shot in High Falls, New York, summer home of director Kazan.[5]

Warren Beatty, while having appeared on television (in particular a recurring role on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis), made his screen debut in this film. He had met Inge the year before while appearing in Inge's play A Loss of Roses on Broadway.[6]

Inge also made his screen debut in the film,[7] as did Sandy Dennis who appeared in a small role as a classmate of Deanie.[6] Marla Adams and Phyllis Diller were others who made their first appearances in this film.[6] Diller's role was based on Texas Guinan, a famous actress and restaurateur, who owned the famous 300 Club in New York City in the 20s.

Reception

[edit]This section contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (August 2024) |

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called the film a "frank and ferocious social drama that makes the eyes pop and the modest cheek burn"; he had comments on several of the performances:[8]

- Pat Hingle "gives a bruising performance as the oil-wealthy father of the boy, pushing and pounding and preaching, knocking the heart out of the lad"

- Audrey Christie is "relentlessly engulfing as the sticky-sweet mother of the girl"

- Warren Beatty is a "surprising newcomer" and an "amiable, decent, sturdy lad whose emotional exhaustion and defeat are the deep pathos in the film"

- Natalie Wood has a "beauty and radiance that carry her through a role of violent passions and depressions with unsullied purity and strength. There is poetry in her performance, and her eyes in the final scene bespeak the moral significance and emotional fulfillment of this film."

Writing in Esquire magazine, however, Dwight Macdonald confirmed the notion that Elia Kazan was "as vulgar a director as has come along since Cecil B. De Mille." He further commented:

I've never been in Kansas, but I suspect that parents there even way back in 1928 were not stupid to the point of villainy and that their children were not sexually frustrated to the point of lunacy...Kazan is "forthright" the way a butcher is forthright when he slaps down a steak for the customer's inspection. [He] won't give up anything that can be exploited.[9]

As for the performances, Variety stated that Wood and Beatty "deliver convincing, appealing performances" and Christie and Hingle were "truly exceptional", but also found "something awkward about the picture's mechanical rhythm. There are missing links and blind alleys within the story. Several times it segues abruptly from a climax to a point much later in time at which is encountered revelations and eventualities the auditor cannot take for granted. Too much time is spent focusing attention on characters of minor significance in themselves."[10] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "The picture does have its theatrical excesses and falls short idealistically in that its morality remains unresolved; nevertheless, it is film-making of the first order and one of the few significant American dramas we have had this year."[11] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post found "beauty and truth" in the story but thought "the parents' incessant nagging and unlistening ears are not convincing" and that Christie and Hingle's characters "could do all that they do in far less footage."[12] Harrison's Reports awarded a grade of "Very Good" and wrote that the adult themes "do not blow up the story into a soap-opera bubble. The emotional cheapness and the sordid crudeness that are evidencing themselves in so many of the yarns being spun, these days, out of the sexual pattern of young, immoral behavior is not to be found here. Instead, you find a poignantly appealing and warmly touching performance of lovely Natalie Wood that gives the story meaning."[13] Brendan Gill of The New Yorker disagreed and slammed the film for being "as phony a picture as I can remember seeing," explaining that Inge and Kazan "must know perfectly well that the young people whom they cause to go thrashing about in 'Splendor in the Grass' bear practically no relation to young people in real life ... one has no choice but to suppose that this unwholesome sally into adolescent sexology was devised neither to instruct our minds nor to move our hearts but to arouse a prurient interest and produce a box-office smasheroo. I can't help hoping they have overplayed their hand."[14]

Time magazine said "the script, on the whole, is the weakest element of the picture, but scriptwriter Inge can hardly be blamed for it" because it had been "heavily edited" by Kazan; the unidentified reviewer called the film a "relatively simple story of adolescent love and frustration" that has been "jargoned-up and chaptered-out till it sounds like an angry psychosociological monograph describing the sexual mores of the heartless heartland."[15]

The film holds a score of 72% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 29 reviews.[16] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 74 out of 100, based on 10 critics, indicating "generally favorable" reviews.[17]

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Actress | Natalie Wood | Nominated | [18] |

| Best Story and Screenplay – Written Directly for the Screen | William Inge | Won | ||

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Foreign Actress | Natalie Wood | Nominated | [19] |

| Directors Guild of America Awards | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Elia Kazan | Nominated | [20] |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Nominated | [21] [5] | |

| Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama | Warren Beatty | Nominated | ||

| Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama | Natalie Wood | Nominated | ||

| Most Promising Newcomer – Male | Warren Beatty | Won | ||

| Laurel Awards | Top Female Dramatic Performance | Natalie Wood | Nominated | |

| Photoplay Awards | Gold Medal | Won | ||

- The film ranked No. 50 on Entertainment Weekly's list of the 50 Best High School Movies.[22] In 2002, the American Film Institute ranked Splendor in the Grass number 47 on its list of the Top 100 Greatest Love Stories of All Time.[23]

Remake

[edit]Splendor in the Grass was re-made as the 1981 television film Splendor in the Grass with Melissa Gilbert, Cyril O'Reilly, and Michelle Pfeiffer.

In popular culture

[edit]The movie's story line and main character inspired a hit song by Shaun Cassidy entitled, "Hey Deanie".[1] It was written by Eric Carmen, who also later recorded the song.[24] Cassidy's rendition reached No. 7 on the US Billboard Hot 100 during the winter of 1978.[25] "Hey Deanie" was the second of two songs directly inspired by the movie, the first being Jackie DeShannon's 1966 song, "Splendor in the Grass".[2]

In 1973 Judy Blume published a young adult novel entitled Deenie. The first few lines of the book have the central character introduce herself and explain that shortly before she was born her mother saw a movie about a beautiful girl named Wilmadeene whom everybody called Deenie for short, and that the first time that she held her baby daughter she knew the baby would turn out beautiful and so named her Deenie too. Blume's Deenie goes on to explain that it took her almost 13 years to find out that the girl in the movie went crazy and "ended up on the funny farm", and that her mother advised her to forget that part of the story.[citation needed]

In True Detective season 2 episode 7 the movie is featured and watched.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "All-Time B.O. Champs", Variety, January 3, 1968 p. 25. Please note these figures refer to rentals accruing to the distributors.

- ^ "1961 Rentals and Potential". Variety. January 10, 1961. p. 13.

- ^ a b "filmsite – Splendor in the Grass".

- ^ "TRAVIS, Staten Island". Forgotten New York. March 11, 2006.

- ^ a b c "Splendor in the Grass (1961)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2013. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Filmreference.com".

- ^ "Bill Inge To Act". Variety. July 6, 1960. p. 3. Retrieved February 6, 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (October 11, 1961). "'Splendor in the Grass' Is at 2 Theatres". The New York Times: 53. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ Macdonald, Dwight. On Movies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969. pp. 141–142.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Splendor In The Grass". Variety. August 30, 1961. 6.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (October 12, 1961). "'Splendor in Grass' Dilemma of Youth". Los Angeles Times. Part III, p. 11.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (October 14, 1961). "Lush Grows Inge's 'Grass'". The Washington Post. A17.

- ^ "'Splendor in the Grass' film review". Harrison's Reports. September 2, 1961. p. 138.

- ^ Gill, Brendan (October 14, 1961). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. 176.

- ^ "Cinema: Love in Kazansas". Time. October 13, 1961. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ^ "Splendor in the Grass". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 28, 2025.

- ^ "Splendor in the Grass". Metacritic. Retrieved September 28, 2025.

- ^ "The 34th Academy Awards (1962) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1963". British Academy Film Awards. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ "14th Annual DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ "Splendor in the Grass". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ "50 Best High School Movies". www.filmsite.org.

- ^ "AFI listing". www.afi.com.

- ^ "Hey Deanie by Shaun Cassidy Songfacts". Songfacts.com. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ^ Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles 1955-1990 - ISBN 0-89820-089-X

- ^ "True Detective Season Two: Everyone's Fired". The Atlantic.

External links

[edit]Splendor in the Grass

View on GrokipediaBackground and Development

Literary Origins

The title of the film Splendor in the Grass derives from William Wordsworth's 1807 poem "Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood," specifically the lines from stanza IX: "Though nothing can bring back the hour / Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower."[7] Published in Poems, in Two Volumes, the ode reflects the Romantic era's emphasis on the sublime power of nature, the intensity of human emotion, and the introspective exploration of personal experience, marking a shift from Enlightenment rationalism toward subjective individualism in early 19th-century British literature.[8] Wordsworth, a key figure in English Romanticism alongside Samuel Taylor Coleridge, composed the work amid the cultural turbulence following the French Revolution, drawing on his own reflections in the Lake District to evoke a nostalgic reverence for natural beauty and inner vision.[9] At its core, the poem grapples with the inevitable fading of childhood innocence, where the young perceive the world with a divine, almost immortal clarity infused by nature's vibrancy, only for adulthood to impose a "shades of the prison-house" that dulls this splendor.[10] Wordsworth consoles that while the "visionary gleam" of youth cannot return, maturity offers philosophical strength through memory, sympathy with nature, and enduring human connections, urging readers to "find / Strength in what remains behind."[11] This transition from untrammeled joy to tempered wisdom underscores Romantic ideals of emotional authenticity and the redemptive role of recollection in confronting loss.[12] Playwright William Inge selected the title during the screenplay's development in 1959, incorporating the poem's lines directly into the narrative when the protagonist Deanie recites them in a classroom scene, symbolizing the characters' struggle with irretrievable youthful passion.[13] Inge's choice aligns the story's depiction of disrupted teenage romance—fractured by economic pressures, family expectations, and premature maturity—with the ode's meditation on innocence eroded by time, evoking a parallel loss of "glory" in personal and natural splendor.[14] Through this literary tether, the film echoes Wordsworth's theme of finding resilience amid irrevocable change, framing its exploration of love's transience within a broader humanistic tradition.[15]Screenplay and Pre-Production

William Inge, a native of Independence, Kansas, began developing the original screenplay for Splendor in the Grass in the late 1950s, drawing heavily from his personal experiences growing up in rural Kansas during the early 20th century.[1] The story was inspired by real people and events Inge knew from his youth, capturing the social constraints and emotional turmoil of small-town life in the fictional New Kira, Kansas.[1] As a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright best known for Picnic (1953), Inge infused the script with his signature naturalistic dialogue and deep psychological insight into characters grappling with societal expectations, a style honed through his Broadway successes that emphasized interpersonal tensions in Midwestern settings.[15] By early 1958, Inge had completed a first draft of the screenplay, which he wrote specifically for his collaborator Elia Kazan, with whom he had worked on the stage production of Inge's play The Dark at the Top of the Stairs.[1] Kazan, impressed by the script's emotional depth and thematic resonance, committed to directing and producing the film, encouraging further revisions to refine its exploration of youthful passion amid familial and cultural pressures.[1] Warner Bros. acquired the rights that year, registering the title with the Motion Picture Association of America and initially scheduling principal photography for May 1959, though delays pushed filming to 1960.[13] Pre-production advanced through 1959 and into 1960, with Inge and Kazan collaborating on script revisions to heighten the dramatic tension between the protagonists' desires and external inhibitions.[16] Budget planning with Warner Bros. focused on a modest production scale suitable for a character-driven drama, allocating resources for period authenticity without extravagant sets.[13] Initial location scouting occurred in New York and Kansas, evaluating sites to evoke the rural Midwest while ultimately favoring East Coast proxies for practicality, as New York's varied landscapes could substitute for the Kansas terrain Inge envisioned.[13] Central to the screenplay's structure is its 1920s setting in post-World War I rural America, a period of fleeting prosperity marked by booming oil wealth and loosening social mores, contrasted with a 1930s framing device amid the Great Depression to underscore themes of lost innocence and enduring regret.[17] This temporal framework, rooted in Inge's observations of economic cycles in his hometown, highlights how historical upheavals amplify personal tragedies, with the script's revisions emphasizing the era's impact on young love and mental health.[1]Production

Casting

Natalie Wood was cast in the lead role of Wilma Dean "Deanie" Loomis, drawing on her established reputation from earlier films like Rebel Without a Cause (1955), which had showcased her ability to portray complex teenage emotions. Director Elia Kazan selected Wood for the part because her vulnerable and intelligent personality aligned closely with Deanie's character, a young woman grappling with sexual repression and societal expectations.[18] The role of Bud Stamper marked Warren Beatty's film debut at age 23, despite his limited acting experience primarily from theater and television. Screenwriter William Inge recommended Beatty to Kazan after spotting him in a television appearance, leading to his screen test and casting; Kazan, known for his method acting approach, provided personal mentoring to guide the newcomer through the role's emotional depth.[19] The supporting cast included seasoned performers and newcomers to enhance the film's naturalistic tone. Pat Hingle portrayed Ace Stamper, Bud's domineering father, bringing gravitas from his stage background. Barbara Loden made her film debut as Virginia "Ginny" Stamper, Bud's wild sister, a role secured through her marriage to Kazan, who favored authentic, personality-driven selections over established stars. Zohra Lampert played Angelina, a school friend adding to the ensemble's youthful dynamic, while Phyllis Love appeared as Toots, contributing to the small-town authenticity.[1][20]Filming Locations and Techniques

Principal photography for Splendor in the Grass took place from May to mid-August 1960, primarily in New York state locations selected to evoke the rural Kansas setting of the story.[13] Exteriors were shot in areas such as High Falls for scenic waterfall sequences, Staten Island's Travis neighborhood for the Loomis family home, and West Islip on Long Island for ranch house scenes mimicking small-town Kansas life.[21][13] School-related scenes, including prom moments, utilized Horace Mann High School in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, while interiors for urban Kansas City elements were filmed at Filmways Studios in New York City.[13] The production wrapped in August 1960, allowing time for post-production ahead of the film's October premiere.[22] The film's visual style was captured on black-and-white 35mm film by cinematographer Boris Kaufman, whose work emphasized emotional intimacy through innovative close-ups that highlighted the nuanced expressions of leads Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty.[23] Kaufman's approach, informed by his prior collaborations with director Elia Kazan, used stark monochrome contrasts to underscore psychological tension and youthful vulnerability, contributing to the film's raw dramatic impact.[24] Kazan employed an improvisational directing style on set, drawing from Method acting techniques to encourage performers' personal input and spontaneous interactions, which enhanced the authenticity of the teen romance and family dynamics.[25] This approach, while fostering deeper character explorations, occasionally led to extended takes and logistical adjustments during the outdoor shoots in upstate New York. In post-production, editor Gene Milford assembled the footage by early 1961, refining the narrative flow to balance intimate dialogues with broader period atmosphere. Composer David Amram crafted the score, integrating folk music elements like guitar and harmonica to reflect the 1920s Midwest setting and amplify emotional undercurrents without overpowering the performances.[26]Plot

In 1928, in the small town of Newley, Kansas, amid the local oil boom, high school students Wilma Dean "Deanie" Loomis and Bud Stamper are deeply in love. Deanie, a popular and virginal girl, is the daughter of hardware store owner Del Loomis and his strict wife. Bud is the son of Ace Stamper, a wealthy oilman who expects Bud to attend Yale University and join the family business, advising him against early marriage. Deanie's mother reinforces traditional values of chastity until marriage, creating tension as the young couple grapples with their physical desires.[1] Unable to consummate their relationship due to these pressures, Bud suggests they wait until marriage, but the strain leads him to break up with Deanie. Heartbroken, Deanie becomes increasingly unstable. At a party, she attempts to seduce Bud publicly, leading to humiliation. Later, overwhelmed by grief, she tries to drown herself in a local river but is rescued. Deanie is subsequently committed to a mental institution for over two years. Meanwhile, Bud attends Yale but struggles academically and emotionally, eventually dropping out and returning home. His wild older sister, Ginny, who has been rejected by her lover, dies in a car crash on New Year's Eve. The stock market crash ruins Ace, who, unable to cope, commits suicide by jumping from an oil derrick.[1] In 1933, Deanie is released from the sanitarium and returns to Newley. She visits her former teacher, who encourages her to move forward. Learning Bud has married Angelina, a former "fast" girl, and has a young son while working in the oil fields, Deanie seeks him out at his ranch. They share a poignant conversation reflecting on their lost youth and past love. Deanie realizes that clinging to the past prevents growth and departs, finding peace in the idea that "though nothing can bring back the hour / Of splendor in the grass, of glory in the flower," blessings remain in the present.[1]Cast

The following table lists the principal cast and their characters:| Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Natalie Wood | Wilma Dean "Deanie" Loomis |

| Warren Beatty | Bud Stamper |

| Pat Hingle | Ace Stamper |

| Audrey Christie | Mrs. Frieda Loomis |

| Barbara Loden | Virginia "Ginny" Stamper |

| Zohra Lampert | Angelina |

| Phyllis Love | Juanita Hedges |

| Sandy Dennis | Kay |