Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of Superfund sites

View on Wikipedia

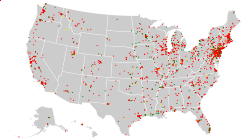

Superfund sites are polluted locations in the United States requiring a long-term response to clean up hazardous material contaminations. Sites include landfills, mines, manufacturing facilities, processing plants where toxic waste has either been improperly managed or dumped. They were designated under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980. CERCLA authorized the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to create a list of such locations, which are placed on the National Priorities List (NPL).[1]

The NPL guides the EPA in "determining which sites warrant further investigation" for environmental remediation.[2] As of June 6, 2024[update], there were 1,340 Superfund sites in the National Priorities List in the United States.[2] Thirty-nine additional sites have been proposed for entry on the list, and 457 sites have been cleaned up and removed from the list.[2] New Jersey, California, and Pennsylvania have the most sites.[3]

Lists of Superfund sites

[edit]U.S. states and federal district

[edit]- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

Insular areas

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "CERCLA". Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Superfund: National Priorities List (NPL)". United States Environmental Protection Agency. June 6, 2024. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ^ Johnson, David (March 22, 2017). "Do You Live Near Toxic Waste? See 1,317 of the Most Polluted Spots in the U.S." Time. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

External links

[edit]List of Superfund sites

View on GrokipediaProgram Background

Establishment and Legal Framework

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) was enacted by the U.S. Congress on December 11, 1980, establishing the federal Superfund program to address uncontrolled hazardous substance releases into the environment that posed risks to public health or welfare.[7] Signed into law by President Jimmy Carter, CERCLA provided the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) with broad authority to identify, investigate, and remediate contaminated sites, including provisions for short-term removal actions to abate immediate threats and long-term remedial actions for permanent cleanup.[3] The Act created the Hazardous Substance Superfund, initially financed through a tax on the chemical and petroleum industries, to cover costs when responsible parties could not be identified or were unwilling to act.[3] CERCLA's legal framework imposes strict, joint, and several liability on potentially responsible parties (PRPs), including current and past owners or operators of sites, generators of hazardous waste, and transporters, without requiring proof of fault or negligence.[8] This liability extends to natural resource damages and response costs, enabling the federal government to compel PRPs to perform cleanups or reimburse the Superfund for government-led efforts.[9] The Act mandates the development of a National Contingency Plan (NCP) to outline response procedures, including the Hazard Ranking System (HRS) for prioritizing sites on the National Priorities List (NPL), which as of its inception focused on the most serious uncontrolled releases.[3] Implementation falls under the President's delegated authority to the EPA, which coordinates with states, tribes, and other agencies, though the program's trust fund faced chronic shortfalls after the initial excise taxes expired in 1995, leading to reliance on general appropriations and recoveries from PRPs.[10] CERCLA does not preempt state laws but allows federal preemption in cases of inconsistency, emphasizing a cooperative federalism approach while prioritizing federal intervention for sites warranting national attention.[8] Subsequent amendments, such as the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986, refined enforcement mechanisms and community involvement requirements but did not alter the core establishment framework from 1980.[10]Site Designation Criteria

Sites qualify for designation as Superfund sites through placement on the National Priorities List (NPL), which identifies locations of known or threatened releases of hazardous substances, pollutants, or contaminants that may present an imminent and substantial endangerment to public health, welfare, or the environment.[1] The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) uses the Hazard Ranking System (HRS), a standardized scoring model, as the principal mechanism to assess and prioritize sites for NPL inclusion.[11] Established under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980 and revised in 1990, the HRS evaluates sites based on three main components: the likelihood of release or migration of hazardous substances, the characteristics of the waste (including toxicity, persistence, and volume), and the potential targets affected (such as human populations, resources, or sensitive ecosystems).[12] The HRS assigns scores ranging from 0 to 100 across four environmental migration pathways—groundwater, surface water, soil exposure, and air migration—with the overall site score determined by the highest pathway score.[11] For each pathway, the score integrates factors like observed releases (e.g., contaminated monitoring wells or observed contamination), potential for migration based on hydrogeological data, waste quantity (measured in observed or potential volumes), and hazard potential (derived from toxicity benchmarks such as carcinogenic risk or chronic toxicity).[13] Targets are scored by proximity to populated areas (e.g., residential or commercial zones with weighted population counts), sensitive environments (e.g., wetlands or national parks), and critical facilities (e.g., wells serving over 500 people daily).[14] A site achieves eligibility for NPL proposal if its HRS score reaches or exceeds 28.5, serving as a cutoff to indicate relative priority among thousands of potential sites without implying a fixed risk level.[11] Following HRS evaluation—typically after a preliminary assessment and site inspection—the EPA proposes sites meeting the threshold for NPL listing via a Federal Register notice, triggering a minimum 60-day public comment period and coordination with state agencies and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry for health consultations.[1] Final designation occurs through rulemaking, after which the site becomes eligible for long-term remedial action under Superfund authorities, including funding from the Superfund Trust Fund or responsible parties.[15] Federal facilities follow a parallel process under CERCLA Section 120, often bypassing HRS if deferred to Department of Defense or Energy programs.[16] This criteria-driven approach ensures prioritization of sites with the greatest demonstrated threats, though scores can be updated with new data during remedial investigations.[17]Current Status and Metrics

Total Sites and Distribution

As of October 1, 2025, the Environmental Protection Agency's National Priorities List (NPL) includes 1,343 Superfund sites requiring long-term remedial action, consisting of 1,186 non-federal sites and 157 federal facilities.[1] An additional 38 sites await final listing after proposal and public comment periods.[1] Cumulatively, 459 sites have been deleted from the NPL upon verification that cleanup remedies protect human health and the environment, though partial deletions have occurred at 118 of these, allowing reuse of uncontaminated portions.[18][19] Superfund sites exhibit a non-uniform geographic distribution reflective of historical concentrations of heavy industry, mining, and waste management. Among the states, New Jersey has the highest count at 113 NPL sites, followed by California (97 sites) and Pennsylvania (95 sites); these figures stem from dense clustering of chemical manufacturing, refineries, and landfills in urban-industrial corridors.[20] Fewer than 10 sites exist in less industrialized states such as Wyoming, South Dakota, and Vermont, underscoring causal links between site prevalence and prior economic activities involving hazardous substances. Federal facilities, often military or energy-related, contribute disproportionately to tallies in states like California and Washington. Sites in U.S. territories remain limited, with none currently on the NPL in areas such as Guam or the U.S. Virgin Islands beyond occasional proposals.[16]Cleanup Completion Rates

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) considers a Superfund site's cleanup complete when it is deleted from the National Priorities List (NPL), signifying that all required response actions have been implemented, the remedy is protective of human health and the environment, and no further EPA remedial action is necessary.[18] As of March 2025, 459 sites have been deleted from the NPL, including both full and partial deletions.[5] With 1,340 sites remaining active on the NPL at that time, this equates to roughly 26% of all sites ever finalized on the list achieving deletion status.[5] Deletion typically follows the completion of physical construction of the selected remedy and a subsequent period—often 10 years or more—of operation, maintenance, and five-year reviews to verify long-term effectiveness.[21] However, progress toward deletion has varied, with annual full-site deletions averaging fewer than 20 in recent fiscal years, including just four sites reaching construction-complete status in fiscal year 2024.[22] Historical trends show a decline in remedial action completions at nonfederal NPL sites, dropping about 37% from fiscal years 1999 through 2013, attributed to reduced federal funding and increasing site complexities.[23] EPA tracks intermediate environmental indicators to gauge partial progress, such as whether current human exposures and groundwater migration of contaminants are under control; these metrics indicate protectiveness at approximately 85-90% of sites but do not equate to full cleanup completion.[21] Delays in achieving deletion often stem from ongoing monitoring needs, unresolved responsible party contributions, or litigation, leaving hundreds of sites in post-construction phases for extended periods.[5] Overall, the Superfund program's deletion rate reflects incremental but slow advancement, with funding constraints exacerbating a 79% real decline in program appropriations since 1999 despite persistent site backlogs.[24]Geographic Listings

Sites by U.S. State and Federal District

The National Priorities List (NPL) comprises hazardous waste sites designated for priority cleanup under the Superfund program, with distribution reflecting historical concentrations of manufacturing, mining, and waste disposal activities. States in the Northeast and Midwest, regions with extensive early-20th-century industrialization, host disproportionately high numbers relative to population or land area. As of January 2016, 1,303 NPL sites existed across the 50 states, excluding the District of Columbia.[20] New Jersey led with 113 sites, attributed to dense chemical and pharmaceutical industries in areas like the Meadowlands and Passaic River corridor.[20] Pennsylvania followed with 95, many linked to steel production and coal-related contamination. California had 97, driven by aerospace, electronics, and agricultural pesticide legacies in the Central Valley and urban bays. By March 2025, the national total reached 1,340 active sites, indicating modest additions amid ongoing designations and deletions upon cleanup completion.[4] The District of Columbia maintains one NPL site, primarily associated with institutional and urban contamination sources.[25] No sites were recorded in North Dakota as of 2016, though peripheral assessments occur in neighboring states; all other states had at least one. The table below details state-level counts from 2016 EPA data, which remain indicative of broader patterns despite incremental changes.[20]| State | Number of Sites |

|---|---|

| Alabama | 13 |

| Alaska | 6 |

| Arizona | 9 |

| Arkansas | 9 |

| California | 97 |

| Colorado | 19 |

| Connecticut | 14 |

| Delaware | 13 |

| Florida | 53 |

| Georgia | 16 |

| Hawaii | 3 |

| Idaho | 6 |

| Illinois | 44 |

| Indiana | 38 |

| Iowa | 11 |

| Kansas | 12 |

| Kentucky | 13 |

| Louisiana | 11 |

| Maine | 13 |

| Maryland | 20 |

| Massachusetts | 32 |

| Michigan | 65 |

| Minnesota | 25 |

| Mississippi | 8 |

| Missouri | 33 |

| Montana | 16 |

| Nebraska | 15 |

| Nevada | 1 |

| New Hampshire | 20 |

| New Jersey | 113 |

| New Mexico | 15 |

| New York | 85 |

| North Carolina | 39 |

| North Dakota | 0 |

| Ohio | 37 |

| Oklahoma | 7 |

| Oregon | 13 |

| Pennsylvania | 95 |

| Rhode Island | 12 |

| South Carolina | 25 |

| South Dakota | 2 |

| Tennessee | 17 |

| Texas | 51 |

| Utah | 15 |

| Vermont | 12 |

| Virginia | 31 |

| Washington | 51 |

| West Virginia | 9 |

| Wisconsin | 37 |

| Wyoming | 2 |