Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

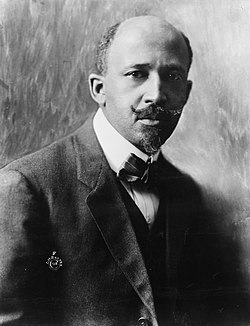

Talented tenth

View on WikipediaThe talented tenth is a term that designated a leadership class of African Americans in the early 20th century. Although the term was created by white Northern philanthropists, it is primarily associated with W. E. B. Du Bois, who used it as the title of an influential essay, published in 1903. It appeared in The Negro Problem, a collection of essays written by leading African Americans and assembled by Booker T. Washington.[1]

Historical context

[edit]

The phrase "talented tenth" originated in 1896 among White Northern liberals, specifically the American Baptist Home Mission Society, a Christian missionary society strongly supported by John D. Rockefeller. They had the goal of establishing Black colleges in the South to train Black teachers and elites. In 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote The Talented Tenth; Theodore Roosevelt was president of the United States and industrialization was skyrocketing. Du Bois thought it was a good time for African Americans to advance their positions in society.[2]

The "Talented Tenth" refers to the one in ten Black men that have cultivated the ability to become leaders of the Black community by acquiring a college education, writing books, and becoming directly involved in social change. In The Talented Tenth, Du Bois argues that these college educated African American men should sacrifice their personal interests and use their education to lead and better the Black community.[3]

He strongly believed that the Black community needed a classical education to reach their full potential, rather than the industrial education promoted by the Atlanta Compromise, endorsed by Booker T. Washington and some White philanthropists. He saw classical education as the pathway to bettering the Black community and as a basis for what, in the 20th century, would be known as public intellectuals:

Men we shall have only as we make manhood the object of the work of the schools—intelligence, broad sympathy, knowledge of the world that was and is, and of the relation of men to it—this is the curriculum of that Higher Education which must underlie true life. On this foundation we may build bread winning, the skill of hand and quickness of brain, with never a fear lest the child and man mistake the means of living for the object of life.[4]

In his later life, Du Bois came to believe that leadership could arise on many levels, and grassroots efforts were also important to social change. His stepson David Du Bois tried to publicize those views, writing in 1972: "Dr. Du Bois' conviction that it's those who suffered most and have the least to lose that we should look to for our steadfast, dependable and uncompromising leadership."[5]

Du Bois writes in his Talented Tenth essay that

The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth; it is the problem of developing the Best of this race that they may guide the Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst.[citation needed]

Later in Dusk of Dawn, a collection of his writings, Du Bois redefines this notion, acknowledging contributions by other men. He writes that "my own panacea of an earlier day was a flight of class from mass through the development of the Talented Tenth; but the power of this aristocracy of talent was to lie in its knowledge and character, not in its wealth."[citation needed]

Du Bois and betterment

[edit]Du Bois believed that college educated African Americans should set their personal interests aside and use their education to better their communities. To him, this meant that the "Talented Tenth" should seek to acquire elite roles in politics. By doing so, Black communities could have representation in government, allowing college educated African Americans to take "racial action."[6]

That is, Du Bois believed that segregation was a problem that needed to be dealt with, and having African Americans in politics would start the process of dealing with it. He also believed that an education would allow one to pursue business endeavors that would better the economic welfare of Black communities, and would also encourage White people to see Black people as more equal to them, thus encouraging integration and allow African Americans to enter the mainstream business world.[6]

The "Guiding Hundredth"

[edit]In 1948, Du Bois revised his "Talented Tenth" thesis into the "Guiding Hundredth". This revision was an attempt to democratize the thesis by forming alliances and friendships with other minority groups that also sought to better their conditions in society. Whereas the "Talented Tenth" only pointed out problems that African Americans were facing in their communities, the "Guiding Hundredth" would be open to mending the problems other minority groups were encountering as well. Moreover, Du Bois revised this theory to stress the importance of morality. He wanted the people leading these communities to have values synonymous with altruism and selflessness. Thus, when it came to who would be leading these communities, Du Bois placed morality above education.[7]

The "Guiding Hundredth" challenged the proposition that the salvation of African Americans should be left to a select few. It reimagined the concept of Black leadership from "The Talented Tenth" by combining racial, cultural, political, and economic ideologies. Without much success,[citation needed] Du Bois tried to keep the idea of education around, taking on a new view that education was a gateway to new opportunities for all people. However, it was viewed as a step in the wrong direction, a threat of reverting to the old ways of thinking, and continued to promote elitism. This revision was also Du Bois' attempt at creating a program for African Americans to follow after World War II, to strengthen their "ideological conscience."[8]

Du Bois emphasized forming alliances with other minority groups because it helped promote equality among all Black people. Both "The Talented Tenth" and "The Guiding Hundredth" exhibit the idea that a plan for political action would need to be evident in order to continue to speak to large populations of Black people. In Du Bois' view, Black people's ability to express themselves in politics was the epitome of Black cultural expression. To gain emancipation was to separate Black and White. The cultures could not combine as a way to avoid and protect the spirit of "the universal black."[8]

Contemporary interpretations

[edit]The concept of the "Talented Tenth" and the responsibilities assigned to it by Du Bois have been received both positively and negatively by contemporary critics.

Positively, some argue that current generations of college-educated African Americans abide by Du Bois' prescriptions by sacrificing their personal interests to lead and better their communities.[7] This, in turn, leads to an "uplift" of those in the Black community. On the other hand, some argue that current generations of college educated African Americans should not abide by Du Bois' prescriptions, and should indeed pursue their own private interest. That is, they believe that college-educated African Americans are not responsible for bettering their communities, whereas Du Bois thinks that they are.[2]

Advocates of Du Bois' prescriptions explain that key characteristics of the "Talented Tenth" have changed since Du Bois' time. One author writes, "The potential Talented Tenth of today is a 'me generation,' not the 'we generation' of the past."[2] That is, the Talented Tenth of today focuses more on its own interests as opposed to the general interests of its racial community. Advocates of Du Bois' ideals believe that African Americans have lost sight of the importance of uplifting their communities. Rather, they have pursued their own interests and now dwell in the fruits of their "financial gain and strivings."[2] Although the percentage of college-educated African Americans has gone up, it is still far lower than the percentage of college-educated White Americans.[2] Therefore, these advocates believe that modern-day members of the "Talented Tenth" should still bear responsibility to use their education to help the African American community, which continues to suffer the effects of racial discrimination.

In contrast, those not in favor of Du Bois' prescriptions believe that individual African Americans have the right to pursue their own interests. Critics of Du Bois, and especially feminist critics, tend to believe that marginalized groups are often "put in boxes" and are expected to either remain within those constructs or abide by their stereotypes. These critics believe that what an African American decides to do with their college education should not become a stereotype. Furthermore, many of Du Bois' original texts, including The Talented Tenth, receive feminist criticism for exclusively using the word "man", implying that only African American men could seek out a college education. According to these feminists, this acts to perpetuate the persistence of a culture that only encourages or allows men to pursue higher education.[2]

Attainability

[edit]This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (April 2022) |

To be a part of this "Talented Tenth," an African American must be college educated. This is a qualification that many view as unattainable for many members of the African American community because the percentage of African Americans in college is much lower than the percentage of White people in college. There are multiple explanations for this fact.

Some argue that this disparity is the result of government policies. For instance, financial aid for college students in low income families decreased in the 1980s because problems regarding monetary inequality began to be perceived as problems of the past.[9] A lack of financial aid can deter or disable an individual from pursuing higher education. Thus, since Black and African-American families make up about 2.9 million of the low income families in the U.S., members of the Black community surely encounter this problem.[citation needed][improper synthesis]

Moreover, because African Americans make up such a large number of the low income families in the U.S., many African Americans face the problem of their children being placed in poorly funded public schools. Because poor funding often leads to poor education, getting into college will be more difficult for students. Additionally, these schools often lack resources that can prepare students for college. For instance, schools with poor funding do not have college guidance counselors, a resource that is available at many private schools and well funded public schools.[10]

Therefore, some argue that Du Bois' prescription or plan for this "Talented Tenth" is unattainable.

See also

[edit]- African-American upper class – Contemporary successors of the Talented Tenth

- Class rank – Comparative measure of students' performance

- Meritocracy and Myth of meritocracy

- Natural aristocracy – similar concept developed by Thomas Jefferson, in a more broad context

- Negro Academy – scholarly institute that published many works of the Talented Tenth

References

[edit]- ^ Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). "The Talented Tenth". In Washington, Booker T. (ed.). The Negro Problem: a series of articles by representative American Negroes of today. New York: James Pott and Company. pp. 31–75. Archived from the original on 2025-04-22.

- ^ a b c d e f King, L'Monique (2013). "The Relevance and Redefining of Du Bois's Talented Tenth: Two Centuries Later". Papers & Publications: Interdisciplinary Journal of Undergraduate Research. 2: 7 – via University of North Georgia.

- ^ Battle, Juan; Wright, Earl (2002). "W.E.B. Du Bois's Talented Tenth: A Quantitative Assessment". Journal of Black Studies. 32 (6): 654–672. doi:10.1177/00234702032006002. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 3180968. S2CID 143962872.

- ^ W.E.B. Du Bois, "The Talented Tenth" (text), Sep 1903, TeachingAmericanHistory.org, Ashland University, accessed 3 Sep 2008

- ^ James, Joy (1997). Transcending the Talented Tenth: Black Leaders and American Intellectuals. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-91763-6.

- ^ a b Gooding-Williams, Robert (2017-09-13). "W. E. B. Du Bois". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ a b Rabaka, Reiland (2003). "W. E. B. Du Bois's Evolving Africana Philosophy of Education". Journal of Black Studies. 33 (4): 399–449. doi:10.1177/0021934702250021. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 3180873. S2CID 144101148.

- ^ a b Jucan, Marius (2012-12-01). "'The Tenth Talented' v. 'The Hundredth Talented': W. E .B. Du Bois's Two Versions on the Leadership of the African American Community in the 20th Century". American, British and Canadian Studies. 19 (2012): 27–44. doi:10.2478/abcsj-2013-0002.

- ^ Carnoy, Martin (1994). "Why Aren't more African Americans Going to College?". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (6): 66–69. doi:10.2307/2962468. ISSN 1077-3711. JSTOR 2962468.

- ^ Boschma, Janie; Brownstein, Ronald (2016-02-29). "Students of Color Are Much More Likely to Attend Schools Where Most of Their Peers Are Poor". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2025-01-25. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

Further reading

[edit]- The Negro Problem, New York: James Pott and Company, 1903

- W. E. B. Du Bois, Dusk of Dawn, "Writings," (Library of America, 1986), p. 842

Talented tenth

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Formulation

Pre-Du Bois Conceptual Roots

The concept of an educated elite within the Black population assuming leadership roles predates W.E.B. Du Bois's formulation, tracing back to mid-19th-century discussions on racial uplift amid emancipation. In his final public address on April 11, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln advocated extending voting rights selectively to "very intelligent" free Black men and those who had served as Union soldiers, estimating this group at approximately one-tenth of the Black population based on contemporary demographics of about 4 million enslaved and freed individuals, with soldiers numbering around 180,000 and educated freemen a small fraction. This proposal reflected an implicit recognition of a natural leadership stratum capable of guiding broader advancement, though it was framed within white paternalism and limited to political enfranchisement rather than comprehensive social elevation. Black intellectuals in the late 19th century further developed these notions, emphasizing the necessity of an exceptional minority to counteract the debilitating legacies of slavery. Alexander Crummell, an Episcopal priest and Pan-Africanist (1819–1898), argued that the Black masses, incapacitated by centuries of enslavement, required guidance from a cultivated vanguard of educated leaders to foster moral, intellectual, and civilizational progress; he viewed this elite as inherently responsible for "lifting" the race through exemplary conduct and institution-building, as articulated in his addresses to the American Negro Academy, founded in 1897 but rooted in his earlier writings from the 1860s onward.[9] Crummell's ideas, influenced by his Cambridge education and encounters with European intellectual traditions, prefigured elite-driven uplift by positing that innate talents, when honed, could redeem the collective without diluting focus on the majority's immediate needs.[10] The specific phrase "talented tenth" emerged in 1896 from white Baptist leader Henry Lyman Morehouse, corresponding secretary of the American Baptist Home Mission Society, in an essay published in The Independent magazine. Morehouse contended that while nine-tenths of Black Americans could thrive with practical, industrial training suited to manual labor, the exceptional tenth—possessing superior natural endowments—demanded advanced liberal education to emerge as teachers, ministers, and professionals capable of inspiring and directing the masses toward self-reliance.[11] This formulation arose amid post-Reconstruction debates over educational philanthropy, contrasting with Booker T. Washington's emphasis on vocationalism at Tuskegee, and underscored a hierarchical view of racial progress where elite cultivation would yield disproportionate societal benefits.[2] Morehouse's concept, drawn from observations of missionary work and census data on Black literacy rates (around 40-50% in the 1890s South), prioritized resource allocation to high-potential individuals to maximize long-term uplift, though it carried assumptions of innate talent distribution verifiable only through selective opportunity.[12]Du Bois's 1903 Essay and Core Thesis

W.E.B. Du Bois's essay "The Talented Tenth," published in September 1903 as a contribution to the anthology The Negro Problem: A Series of Articles by Representative American Negroes of To-Day, introduced the concept that the African American race would advance through the leadership of its most capable members, estimated at ten percent of the population.[1] [3] Du Bois argued that "the Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men," referring to this elite group as the "best blood of the black race" who, through superior intellect and moral character, would guide the masses toward progress.[1] [10] The core thesis emphasized cultivating these leaders via rigorous higher education, particularly at institutions offering classical liberal arts curricula rather than vocational training. Du Bois contended that the Talented Tenth must function as "leaders of thought and missionaries of culture among their people," with no others equipped for this role, as they would demonstrate self-sacrifice and dedication to racial upliftment.[13] [1] To substantiate the existence and viability of this class, he cited data on Black college graduates from institutions like Harvard, Fisk, and Atlanta University, noting their production of professionals such as physicians, lawyers, and educators who had risen despite systemic barriers.[1] Du Bois outlined two primary objectives in the essay: first, to demonstrate the Talented Tenth's historical worthiness for leadership through empirical examples of achievement; second, to prescribe methods for their further education and development, advocating for selective investment in elite training to maximize societal impact.[1] This approach rested on the assumption that broad industrial education alone would fail to elevate the race, necessitating a vanguard capable of intellectual and cultural innovation.[10]Theoretical Foundations

Assumed Leadership Mechanism

Du Bois envisioned the Talented Tenth assuming leadership primarily through an elitist, top-down mechanism rooted in higher education and moral exemplarity, whereby this educated cadre would filter culture and progress downward to the masses. He asserted that "the Talented Tenth rises and pulls all that are worth the saving up to their vantage ground," emphasizing that no civilization had ever advanced from the bottom upward but rather through the influence of an exceptional minority acting as an "aristocracy of talent and character."[3] This process presumed the natural percolation of the most capable individuals into positions of influence, where they would set community ideals, inspire emulation, and counteract degradation among the lower strata.[14] Central to this mechanism was the role of the Talented Tenth as "leaders of thought and missionaries of culture," tasked with developing intelligence, sympathy, and broad knowledge to civilize their people. Du Bois argued that colleges should prioritize training this group to produce teachers, professionals, and reformers who would then educate and elevate the broader population, stating, "Out of the colleges... went teachers, and around the normal teachers clustered other teachers."[13] He assumed their leadership would emerge organically from merit-based achievement in professions and intellect, unhindered in principle by prejudice once proven, as historical examples showed educated Negroes leading despite slavery and discrimination.[3] The mechanism further relied on a selective filtration: by focusing resources on the "Best of this race" to guide the "Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst," the Talented Tenth would foster manhood defined by "intelligence, broad sympathy, [and] knowledge of the world," thereby enabling collective advancement without diluting efforts on universal mass education.[14] This presupposed that the elite's moral and intellectual superiority would compel deference and upward mobility among the capable, while the unworthy elements self-selected out, aligning with Du Bois's view that races are "saved by [their] exceptional men."[13]Emphasis on Higher Education and Merit

In W.E.B. Du Bois's formulation of the Talented Tenth, higher education served as the primary mechanism for identifying and cultivating exceptional Black leaders, prioritizing rigorous academic training over vocational skills. Du Bois contended that "the best and most capable of their youth must be schooled in the colleges and universities of the land," emphasizing curricula in Greek, Latin, mathematics, and philosophy to foster broad intelligence, moral character, and cultural understanding.[15] [14] This approach contrasted with industrial education models, which Du Bois viewed as insufficient for producing guiding elites, arguing instead that liberal arts education enabled the "transmission of knowledge and culture" through "quick minds and pure hearts."[14] Merit formed the cornerstone of selection for the Talented Tenth, defined by innate talent and demonstrated excellence rather than social status or heredity. Du Bois asserted that the race would be "saved by its exceptional men," requiring the development of "the Best of this race" to elevate the masses from the influence of the "Worst."[15] [14] Identification occurred through performance in higher education, where the talented naturally rose to form an "aristocracy of talent," capable of setting community ideals and directing social movements.[14] By 1903, Du Bois cited evidence of approximately 2,000 college-educated Black men who had already trained 50,000 others in morals and manners, illustrating the meritocratic filtering of progress "from the top downward."[15] This emphasis positioned the college-bred Negro as the "group leader," tasked with missionary-like roles in disseminating culture and thought leadership among the broader population.[15] Du Bois warned that neglecting higher education for the talented risked systemic failure, as "to attempt to establish any sort of a system of common and industrial school training, without first providing for the higher training of the very best teachers," wasted resources.[14] Thus, merit-based higher education was theorized not merely as personal advancement but as causal prerequisite for racial uplift, with the Talented Tenth pulling "all that are worth the saving up to their vantage ground."[15]Contemporary Debates in Du Bois's Era

Conflict with Booker T. Washington's Approach

Du Bois articulated a fundamental opposition to Washington's philosophy of racial uplift, which prioritized vocational training and economic accommodation over higher education and political confrontation. In his 1903 essay "The Talented Tenth," Du Bois contended that the most capable segment of the Black population—estimated at one in ten—required rigorous liberal arts education to develop intellectual leaders capable of advocating for full civil rights, contrasting Washington's emphasis on industrial skills for the masses to foster self-reliance without challenging white supremacy.[1] Washington's 1895 Atlanta Compromise speech had promoted gradual economic progress through manual labor and deference to segregation, urging Blacks to "cast down your bucket where you are" in agriculture and industry, a stance Du Bois viewed as conceding too much ground on voting rights and higher learning.[16] This rift intensified in Du Bois's chapter "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others" from The Souls of Black Folk (1903), where he accused Washington of inducing Blacks to relinquish three core demands: political power through enfranchisement, persistent civil rights agitation, and advanced education for the exceptional few. Du Bois argued that Washington's dominance, bolstered by Northern philanthropy and Southern tolerance, had sidelined the role of a cultivated elite in favor of a "policy of submission" that risked perpetuating subordination by limiting aspirations to trades like farming and mechanics.[17] He posited that true progress demanded the Talented Tenth's emergence as a "vanguard of revolt and progress," trained in universities to secure legal equality and cultural elevation, rather than Washington's mass-oriented Tuskegee model, which enrolled over 1,500 students by 1900 primarily in practical curricula.[18] The disagreement extended to leadership paradigms: Washington envisioned uplift through exemplary individual achievement and institutional building at Tuskegee, founded in 1881, without elite exceptionalism, while Du Bois's framework relied on the top decile's meritocratic guidance to counteract widespread illiteracy—over 44% among Southern Blacks in 1900 per U.S. Census data—by example and advocacy.[19] Du Bois critiqued Washington's accommodation as empirically shortsighted, noting that post-Reconstruction disenfranchisement laws like literacy tests had already eroded political gains, rendering economic focus alone insufficient without educated agitators to dismantle Jim Crow barriers.[20] This philosophical clash polarized Black intellectuals, with Du Bois co-founding the Niagara Movement in 1905 partly to counter Washington's influence through the National Negro Business League, established in 1900 to promote entrepreneurship over protest.[21]Responses from Other Black Intellectuals

Kelly Miller, dean of Howard University's College of Arts and Sciences, responded to Du Bois's thesis by directing the Talented Tenth toward the ministry as a primary avenue for racial leadership and moral influence. In his pamphlet The Ministry: The Field for the Talented Tenth, Miller argued that college-educated Black clergy possessed the intellectual and ethical capacity to unify the race, countering secular skepticism and addressing the spiritual needs of the masses amid widespread disillusionment with organized religion.[22] He emphasized that ministers from this elite could serve as "leaders of thought" in communities, fostering self-reliance and ethical development without relying solely on political agitation or industrial training.[23] Archibald H. Grimké, a lawyer, diplomat, and president of the American Negro Academy from 1903 to 1919, aligned with Du Bois's vision through the Academy's promotion of advanced scholarship among Black intellectuals. The organization, established in 1897, functioned as a intellectual hub for the Talented Tenth, publishing works on history, literature, and sociology to cultivate leaders capable of refuting racial stereotypes and advocating for higher education.[24] Grimké's leadership reinforced the idea that a cultivated minority could elevate the entire race by producing rigorous scholarship and public discourse, though he prioritized diplomatic and legal avenues over Du Bois's broader cultural missionary role. William Monroe Trotter, a Harvard-educated journalist and fierce critic of Booker T. Washington, endorsed the Talented Tenth's emphasis on classical education as essential for militant civil rights advocacy. Co-founding the Niagara Movement with Du Bois in 1905, Trotter advocated training an elite cadre to demand immediate equality, viewing vocational-focused approaches as insufficient for combating disenfranchisement and lynching. His newspaper, The Boston Guardian, amplified calls for educated Black professionals to lead uncompromising protests, interpreting the tenth's role as agitators for constitutional rights rather than gradual uplifters.[25]Evolution Under Du Bois

Shift to the "Guiding Hundredth"

In 1948, W.E.B. Du Bois delivered "The Talented Tenth Memorial Address" to the Sigma Pi Phi fraternity, where he re-examined and revised his earlier thesis, transforming the "Talented Tenth" into the doctrine of the "Guiding Hundredth."[5] This evolution reflected Du Bois's assessment that the original concept's reliance on a naturally emerging educated elite had proven insufficient amid post-World War II global shifts, including decolonization movements and the rise of socialist influences, necessitating a more deliberate, organized leadership structure.[5][26] The "Guiding Hundredth" narrowed the focus to roughly 30,000 individuals—about 1% of the Black population at the time—who would serve as a compact cadre committed to systematic guidance of the broader community.[5] Unlike the broader Talented Tenth, which assumed leadership would arise organically from college-educated talent, the new model proposed a formalized organization featuring a directing council of experts and a paid executive committee to coordinate efforts in education, economic planning, and cultural alliances with other marginalized groups worldwide.[5] Du Bois emphasized this group's role in "drawing out human powers" through collective struggle, sacrifice, and service, incorporating Marxian principles of class solidarity and rejecting individualistic ascent in favor of enforced communal responsibility.[5][27] Du Bois articulated the revision as follows: "This, then, in my re-examined and restated theory of the 'Talented Tenth,' which has thus become the doctrine of the 'Guiding Hundredth.'"[5] The shift aimed to mitigate the observed failures of many within the original tenth, who prioritized personal gain over racial uplift, by institutionalizing accountability and broader participation in leadership selection.[26] This framework sought to foster democratic elements within an elite vanguard, aligning with Du Bois's growing emphasis on international proletarian alliances while preserving merit-based selection rooted in intelligence, achievement, and opportunity.[5][28]Du Bois's Repudiation and Reasons

In 1948, W. E. B. Du Bois delivered an address titled "The Talented Tenth" to the Sigma Pi Phi fraternity, in which he explicitly re-examined and revised his 1903 concept, transforming it from reliance on a naturally emerging educated elite comprising roughly 10 percent of the Black population into the more structured "Guiding Hundredth."[5] This shift reduced the leadership cadre to approximately 1 percent, or 30,000 individuals, selected and trained deliberately through higher education with an emphasis on specialized qualities like self-sacrifice, sympathy for the masses, and alignment with global cultural and economic forces.[5] Du Bois proposed organizing this group under a directing council and executive committee to coordinate efforts in education, economic planning, and advocacy, reflecting his evolving view that unstructured exceptionalism alone could not drive racial progress.[5] Du Bois attributed the original theory's shortcomings to its overreliance on innate talent without sufficient safeguards for character and commitment, admitting that he had "failed to emphasize" the need for "honest" and "self-sacrificing" leaders in his initial formulation.[6] Empirical observation over four decades revealed that many in the supposed Talented Tenth—college-educated professionals—had not fulfilled their anticipated role in uplifting the broader Black population; instead, a significant portion pursued personal wealth and social status, fostering a detached, "moneyed elite" prone to corruption and disconnection from the masses' struggles.[29] This failure manifested in limited widespread progress despite increased Black educational attainment, as the elite often prioritized individual advancement over collective sacrifice or alliances with labor and progressive movements.[30] Broader ideological evolution underpinned the revision, as Du Bois, increasingly influenced by Marxist principles in his later years, critiqued the original idea's individualism for neglecting systemic economic barriers and the necessity of organized, class-conscious action.[5] He argued that true leadership required integration with global proletarian forces and a "new world culture" beyond isolated racial exceptionalism, warning that without deliberate structure, the Talented Tenth risked perpetuating internal divisions rather than resolving them through coordinated economic and political strategy.[5] This restatement aimed to democratize leadership by mandating alliances across classes and emphasizing planned cooperation, though Du Bois maintained faith in education's centrality while subordinating it to collective mechanisms.[5]Empirical Assessment

Historical Outcomes and Data on Black Leadership

Despite the rise of a Black intellectual and professional elite—embodying Du Bois's "talented tenth" concept—empirical data indicate limited broad-based upliftment for the wider Black population, with persistent socioeconomic gaps and challenges in communities under prolonged Black political leadership. U.S. Census and Federal Reserve analyses show Black household wealth at about one-sixth of white household wealth in 2020, a ratio that improved from 1:60 post-emancipation to 1:10 by 1920 but has stagnated or widened relative to income growth since the mid-20th century, amid factors like lower homeownership (44% for Blacks vs. 74% for whites in 2022) and asset accumulation disparities.[31][32] Black median income reached 59% of white median income by 2019, up from 40% in 1967, yet this progress stalled post-2000, coinciding with expansions in Black elite representation without proportional gains in family structure stability or poverty reduction beyond initial civil rights-era advances.[33][34] Educational outcomes reflect partial elite-driven progress but enduring gaps. Black high school completion rates climbed to 88% by 2019, approaching the national average of 90%, largely through expanded access post-Brown v. Board of Education (1954).[35] However, college degree attainment lags at 30.8% for Black adults versus 47.1% for whites as of recent surveys, while NAEP scores show Black-white reading and math gaps narrowing modestly from the 1970s (e.g., 1.2 standard deviations in 1971 to 0.9 by 2008) but persisting at 0.8-1.0 standard deviations through 2022, with Black 13-year-olds' gains plateauing amid cultural and behavioral factors like family instability.[36][37][38] Studies attribute stalled convergence not solely to discrimination but to differences in study habits, school choice, and household environments, challenging assumptions of elite leadership as sufficient for mass educational parity.[39] In urban centers with extended Black mayoral leadership—testing the talented tenth's guiding role—outcomes often show fiscal distress, population exodus, and elevated crime despite some targeted ZIP-code gains. Cities like Detroit (Black mayor since 1974) experienced bankruptcy in 2013 after decades of leadership, with population dropping 60% since 1950 amid manufacturing loss and governance issues; Baltimore (Black mayor since 1971) maintains homicide rates exceeding 50 per 100,000, far above the national average of 5, correlating with underclass dysfunction rather than elite policy success.[40] NBER research finds Black political representation boosts localized Black economic metrics modestly (e.g., income in majority-Black areas), yet broader city-level data reveal no systemic crime reduction or wealth convergence, with high-violence locales like New Orleans and St. Louis (frequent Black leadership) sustaining rates 10-15 times national norms through 2020.[41][42] Recent post-2020 crime dips in some Black-led cities (e.g., 20-40% homicide reductions in Memphis and Birmingham) stem from policing reforms rather than inherent elite efficacy, underscoring causal limits of representation alone.[43][44]| Metric | Black Outcome (Recent Data) | White Comparison | Historical Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth Ratio | 1:6 (2020) | Baseline | Narrowed 1900-1950, stalled since[31] |

| HS Completion | 88% (2019) | 90% national | Near parity post-1960s[35] |

| College Degree | 30.8% adults | 47.1% | Gap persistent[36] |

| Homicide Rate (Select Cities) | 40-70/100k (e.g., Baltimore) | 3-5/100k national | Elevated under long Black leadership[40] |