Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

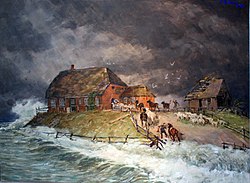

A terp, also known as a wierde, woerd, warf, warft, werf, werve, wurt or værft, is an artificial dwelling mound found on the North European Plain that has been created to provide safe ground during storm surges, high tides and sea or river flooding. The various terms used reflect the regional dialects of the North European region.

Terps are found in the coastal regions of the Netherlands, particularly in the provinces of Zeeland, Friesland and Groningen, as well as in southern Denmark and northwestern Germany. Before the construction of dykes, these mounds provided protection against floodwaters that regularly disrupted daily life. They are especially common in East Frisia (Ostfriesland) and Nordfriesland in Germany. On the Halligen islands in Kries Norfriesland, people continue to live on terps without the protection of dykes. Terps are also present in the Rhine and Meuse river plains in central Netherlands. Further examples occur in North Holland, such as Avendorp near Schagen, and in the towns of Bredene and Leffinge near Oostende in Belgium. Additional terps are located at mouth of the IJssel River, including at Kampereiland in the province of Overijssel, as well as on the former island of Schokland in the Zuiderzee, now part of the reclaimed Noordoostpolder. An old terp, known as Het Torp is also located beneath the town of Den Helder in North Holland.

Terpen in the province of Friesland

[edit]In the Dutch province of Friesland, an artificial dwelling hill is called terp (plural terpen).[1] Terp means "village" in Old Frisian and is cognate with English thorp, Danish torp, German Dorf, modern West Frisian doarp and Dutch dorp.

Terpen were built to "curb natural influences" such as floods by being a part of a network of terpen that rerouted large-scale flooding.[1]

Historical Frisian settlements were built on artificial terpen up to 15 metres (49 ft) high to be safe from floods in periods of rising sea levels. The first terp-building period dates to 500 BC, the second from 200 BC to 50 BC. In the mid-3rd century, the rise of sea level was so dramatic that the clay district was deserted, and settlers returned only around AD 400. A third terp-building period dates from AD 700 (Old Frisian times). This ended with the coming of the dike somewhere around 1200. During the 18th and 19th centuries, many terps were destroyed to use the fertile soil they contained to fertilize farm fields. Terpen were usually well fertilized by the decay of the rubbish and personal waste deposited by their inhabitants over centuries.

Wierden in the province of Groningen

[edit]In the Dutch province of Groningen an artificial dwelling mound is called a wierde (plural wierden). As in Friesland, the first wierde was built around 500 BC or maybe earlier.

List of artificial dwelling mounds

[edit]Place names in the Frisian coastal region ending in -werd, -ward, -uert etc. refer to the fact that the village was built on an artificial dwelling mound (wierde). The greater part of the terp villages, though, have names ending in -um, from -heem or -hiem, meaning (farm)yard, grounds. There are a few village names in Friesland ending with -terp (e.g. Ureterp), referring not to a dwelling mound but merely to the Old Frisian word for village. The first element of the toponyms is quite often a person's name or is simply describing the environmental features of the settlement (e.g. Rasquert (prov. Groningen) Riazuurđ: wierde with reed, where reed grows).

Some 1,200 terpen are recorded in Groningen and Friesland alone. They range from abandoned settlements to mounds with only one or a few farmhouses, to larger villages and old towns. A few of them are listed below.

Friesland

[edit]- Aalsum (West Frisian: Ealsum)

- Bolsward (Boalsert)

- Britsum

- Cornwerd (Koarnwert)

- Dokkum

- Ee

- Ferwert

- Ginnum

- Hegebeintum

- Hitzum

- Jannum

- Jouswier

- Leeuwarden (Ljouwert)

- Metslawier

- Wijnaldum

Groningen

[edit]Northern Germany

[edit]- Loquard (East Frisia)

- Rysum (East Frisia)

- Eckwarden (Butjadingen)

- Itzwärden (Land Wursten)

See also

[edit]Literature

[edit]- Dirk Meier (2006), Die Nordseeküste: Geschichte einer Landschaft (in German), Heide: Boyens, ISBN 978-3-8042-1182-7

- Moritz Heyne (1899): Das deutsche Wohnungswesen. Von den ältesten geschichtlichen Zeiten bis zum 16. Jahrhundert, Bremen 2012.

References

[edit]External links

[edit]- Warften/Wurten (page of the Society for Schleswig-Holstein History)

- Webseite zu den Warftendörfern Ziallerns und Rysum (private site)

- Historical site of Wüppel in the Wangerland

- Water supply in the North Frisian Marshland (private site)

- Manual making a Terp in 12 Steps (post of the Frisia Coast Trail)

- Vereniging voor terpenonderzoek (Foundation for terp research, the Netherlands)