Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tri-oval

View on Wikipedia

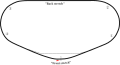

A tri-oval is a shape which derives its name from the two other shapes it most resembles, a triangle and an oval. Rather than meeting at sharp, definable angles as the sides of a triangle do, in a tri-oval these angles are instead rounded into smooth curves.[1]

While an oval has four turns, a tri-oval has six. More formally, according to the four-vertex theorem, every smooth simple closed curve has at least four vertices, points where its curvature reaches a local minimum or maximum. In a tri-oval, there are six such points, alternating between three minima and three maxima.

Use in racetracks

[edit]

This term is most often used to describe the shape of many automobile racetracks.

The use of the tri-oval shape for automobile racing was conceived by Bill France Sr. during the planning for Daytona. The triangular layout allowed fans in the grandstands an angular perspective of the cars coming towards and moving away from their vantage point. Traditional ovals (such as Indianapolis) offered only limited linear views of the course, and required fans to look back and forth much like a tennis match. The tri-oval shape prevents fans from having to "lean" to see oncoming cars, and creates more forward sight lines.

In other racing vernacular, the term "tri-oval" is also used to specifically describe the part of the track which represents the top triangular point of the course, which is used as the main stretch, the pit straight and usually the start–finish line. It is recognizable in most tracks by a manicured grass area.

The modern tri-ovals were often called cookie cutters because of their (nearly) identical shape and identical kind of races. [by whom?]

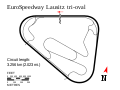

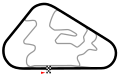

| Type | Examples | Maps |

|---|---|---|

| rounded triangle | Trióvalo Bernardo Obregón, EuroSpeedway Lausitz, Pocono Raceway, Sanair Super Speedway, Walt Disney World Speedway |   , ,  , ,  , ,

|

| Daytona type | Daytona International Speedway, Talladega Superspeedway |  , ,

|

| Las Vegas type | Chicagoland Speedway, Kansas Speedway, Kentucky Speedway, Las Vegas Motor Speedway, Nashville Superspeedway, Phakisa Freeway |  , ,  , ,  , ,  , ,  , ,

|

See also

[edit]- Bean curve, a quartic curve

- n-ellipse, a family of curves that includes some tri-ovals

- Reuleaux triangle, also called a spherical triangle

References

[edit]- ^ "NASCAR Glossary T-Z". NASCAR. Retrieved 6 December 2009.