Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

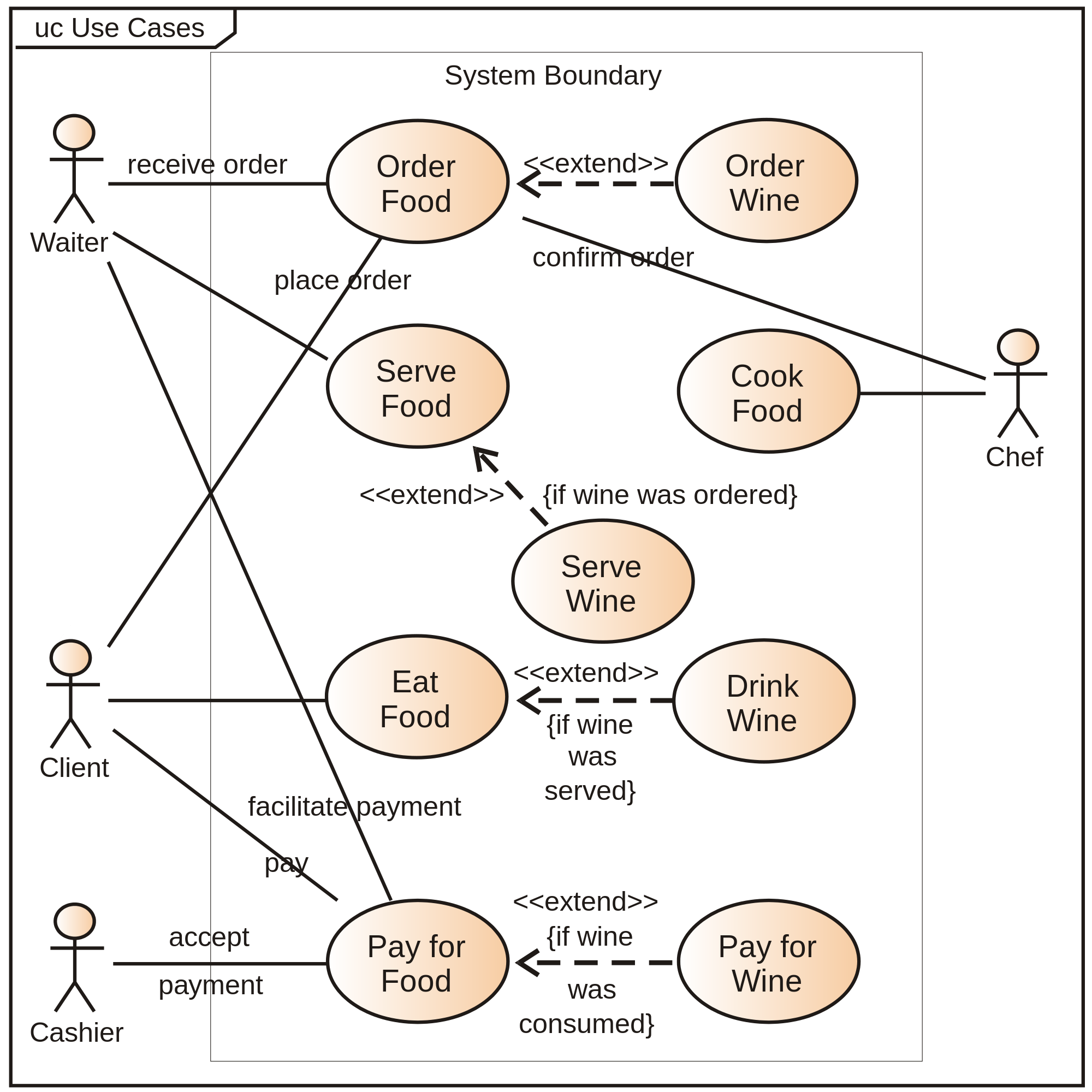

Use case diagram

View on Wikipedia

| UML diagram types |

|---|

| Structural UML diagrams |

| Behavioral UML diagrams |

A use case diagram[1] is a graphical depiction of a user's possible interactions with a system. A use case diagram shows various use cases and different types of users the system has and will often be accompanied by other types of diagrams as well. The use cases are represented by either circles or ellipses. The actors are often shown as stick figures.

Application

[edit]While a use case itself might drill into a lot of detail about every possibility, a use-case diagram can help provide a higher-level view of the system. It has been said before that "Use case diagrams are the blueprints for your system".[2][3]

Due to their simplistic nature, use case diagrams can be a good communication tool for stakeholders. The drawings attempt to mimic the real world and provide a view for the stakeholder to understand how the system is going to be designed. Siau and Lee conducted research to determine if there was a valid situation for use case diagrams at all or if they were unnecessary. What was found was that the use case diagrams conveyed the intent of the system in a more simplified manner to stakeholders and that they were "interpreted more completely than class diagrams".[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Use case". Unified Modeling Language 2.5.1. OMG Document Number formal/2017-12-05. Object Management Group Standards Development Organization (OMG SDO). December 2017. p. 639.

- ^ "Chapter 5. UML & Requirement Diagram (1. Use Case Diagram)". Visual Paradigm User's Guide. Visual Paradigm Community Circle. May 11, 2018.

- ^ Brett D. McLaughlin; Gary Pollice; David West (December 1, 2006). Head First Object Oriented Analysis and Design. Shroff Publishers & Distributors Pvt Ltd. p. 297. ISBN 978-8-184-04221-4.

- ^ Keng Siau; Lihyunn Lee (October 7, 2004). "Are use case and class diagrams complementary in requirements analysis? An experimental study on use case and class diagrams in UML". Requirements Engineering. 9: 229–237. doi:10.1007/s00766-004-0203-7.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gemino, A., Parker, D.(2009) "Use case diagrams in support of use case modeling: Deriving understanding from the picture", Journal of Database Management, 20(1), 1-24.

- Jacobson, I., Christerson M., Jonsson P., Övergaard G., (1992). Object-Oriented Software Engineering - A Use Case Driven Approach, Addison-Wesley.

- Kawabata, R., Kasah, K. (2007). "Systems Analysis for Collaborative System by Use Case Diagram", Journal of Integrated Design & Process Science, 11(1), 13–27.

- Brett D. McLaughlin; Gary Pollice; David West (December 1, 2006). Head First Object Oriented Analysis and Design. Shroff Publishers & Distributors Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-8-184-04221-4.

Use case diagram

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

A use case diagram is a behavioral diagram defined in the Unified Modeling Language (UML) that provides a graphical representation of the functional specifications of a system, illustrating the interactions between external entities known as actors and the system's use cases to demonstrate observable behaviors of value. It captures the high-level requirements by focusing on what the system should accomplish from an external viewpoint, without specifying the internal implementation details or processes. The primary role of a use case diagram is to model system functionality in terms of end-user goals, enabling stakeholders to understand and validate the system's intended behaviors early in the development process.[2] By depicting use cases as units of useful functionality performed in collaboration with actors, the diagram highlights the external perspective on the system's capabilities, distinguishing it from structural diagrams like class diagrams that focus on internal components and relationships.[2] At its core, the basic structure of a use case diagram includes a system boundary that encloses the use cases representing the system's services, with actors positioned outside this boundary to signify their role in initiating or participating in those use cases through defined relationships. This structure emphasizes the black-box view of the system, prioritizing functional requirements and external interactions over sequence of events or data flows seen in other UML behavioral diagrams such as activity or sequence diagrams.[2]History and Standards

The concept of use cases originated in the late 1980s through the work of Ivar Jacobson, a Swedish computer scientist at Ericsson, who developed textual and visual modeling techniques for specifying system behaviors from a user's perspective. In 1987, Jacobson presented these ideas at the OOPSLA conference, laying the groundwork for use case methodology in object-oriented analysis. This approach was further formalized in his 1992 book, Object-Oriented Software Engineering: A Use Case Driven Approach, which introduced use cases as a core practice for capturing functional requirements in software development.[4][5][6] The use case diagram emerged as part of the Unified Modeling Language (UML) in the mid-1990s, driven by the collaboration of Jacobson with Grady Booch and James Rumbaugh—known as the "Three Amigos"—at Rational Software. Their efforts unified various object-oriented modeling notations, incorporating Jacobson's use cases into a standardized graphical representation. UML version 1.0 was submitted to the Object Management Group (OMG) in January 1997, with version 1.1 adopted as the first official standard in November 1997, where use case diagrams were defined as a key behavioral diagram for depicting system interactions with actors.[7][8][9] UML evolved through subsequent revisions to enhance expressiveness and clarity in use case modeling. The major update in UML 2.0, released in July 2005, refined use case diagrams by improving support for relationships and stereotypes, making them more suitable for complex systems. Further iterations culminated in UML 2.5.1, adopted by OMG in December 2017, which remains the current standard and details use case diagrams in its superstructure specification under behavioral diagrams (sections 15–18). These standards are maintained by the OMG to ensure interoperability in software engineering practices.[10][11][12]Components

Actors

In use case diagrams, actors represent external entities that interact with the system, such as human users, other software systems, hardware devices, or even abstract entities like time that trigger events. These actors embody roles rather than specific individuals or instances, allowing them to encapsulate the perspective from which the system is utilized or affected. According to the Unified Modeling Language (UML) 2.5 specification, an actor is defined as a kind of classifier that specifies a coherent set of roles that users of an entity can play when interacting with the entity, and actors may be connected to use cases through associations to denote interactions. Actors are graphically depicted as simple stick figures in UML notation, consisting of a head, body, and limbs to symbolize human-like roles, though alternative icons may be used for non-human actors like systems or devices to enhance clarity. This representation emphasizes their external nature, distinguishing them from internal system elements. The stick figure notation has been standard since early UML versions and facilitates quick identification in diagrams.[13] Actors are classified into primary, secondary, and generalized types based on their interaction patterns with use cases. Primary actors are those that initiate a use case to achieve a goal and directly benefit from its outcome, representing the main stakeholders driving system functionality. For instance, a "Customer" in an e-commerce system acts as a primary actor by initiating actions like placing an order. Secondary actors, also known as supporting actors, do not initiate use cases but provide essential services or resources to enable them, often appearing on the right side of diagrams for convention. An example is a "Payment Gateway" external API that processes transactions on behalf of the e-commerce system. Generalized actors involve inheritance relationships, where a more specific actor (e.g., "Registered Customer") inherits properties from a general one (e.g., "Customer"), allowing reuse and specialization of roles without redundancy. These type distinctions, while not formally mandated in UML, are widely adopted in practice to clarify responsibilities and improve diagram readability.[14][15] In the diagram, actors are positioned outside the system boundary—a rectangle enclosing the use cases—to underscore their external status, and they connect to relevant use cases via solid lines called associations, which may include multiplicity or stereotypes to specify interaction details. This placement and connection mechanism highlights how actors drive or support system behavior without delving into internal implementation. For example, in an automated teller machine (ATM) system, the "Bank Customer" primary actor associates with use cases like "Withdraw Cash," while the "Bank Information System" secondary actor associates with "Validate Account" to provide backend support.[15][14]Use Cases

In UML use case diagrams, a use case represents a unit of useful functionality provided by the system, encapsulating a sequence of actions that yields an observable result of value to one or more actors.[11] This functionality is specified from an external perspective, focusing on what the system does rather than how it achieves the result internally. Use cases are characterized as atomic units of behavior, though they may incorporate sub-use cases through relationships to handle variations or common steps.[11] They are typically named using a verb-noun phrase to clearly indicate the action and its target, such as "Withdraw Cash" for an ATM system or "Place Order" in an e-commerce application.[16] This naming convention ensures clarity and aligns with the goal-oriented nature of use cases, as originally emphasized by Ivar Jacobson in his foundational work on object-oriented analysis. Use cases should be phrased as goal-oriented descriptions from the user's perspective, avoiding implementation-specific or UI-oriented terms (for example, prefer "Authenticate User" over "Login"). Improper naming, such as using implementation details instead of user goals, is a common mistake that can lead to lower scores in academic grading or professional evaluations. Within the use case diagram, use cases are positioned inside the system boundary to denote the functionalities offered by the system as a black box, abstracting away implementation details like algorithms or data structures.[11] This placement highlights the system's external interface, where interactions with actors occur via associations that connect actors to the relevant use cases. The scope of use cases is limited to functional requirements, describing the observable behaviors and outcomes without addressing non-functional aspects such as performance, security, or usability metrics.[11] This focus ensures that use cases serve as a high-level model for requirements elicitation, prioritizing the "what" over the "how" or "how well."[16]System Boundary

In UML use case diagrams, the system boundary is depicted as a rectangular box that encloses all the use cases of the system under consideration, with the name of the system typically placed in the top-left corner of the rectangle.[17] This graphical element serves as a visual delimiter, clearly distinguishing the internal functionalities represented by the use cases from the external environment, thereby defining the scope of the system being modeled.[18] The primary purpose of the system boundary is to establish the conceptual limits of the subject—often the system itself—by grouping related use cases within it while positioning actors and other external elements outside.[17] Only the use cases that pertain to the system's observable behaviors are placed inside this boundary; actors, which interact with the system but are not part of it, remain external to reinforce the separation between the system and its surroundings.[18] This enclosure does not imply formal ownership in the model but rather indicates the applicability of the enclosed use cases to the specified subject.[17] In more complex diagrams, variations may include multiple system boundaries to represent subsystems or modular components, each enclosing a subset of use cases relevant to that subsystem while maintaining the overall system's scope.[19] Such boundaries can be styled with adjustable opacity or dividing lines for clarity, but they remain non-UML model elements used solely for diagrammatic organization.[17]Relationships

Association

In use case diagrams, an association represents the fundamental relationship between an actor and a use case, depicted as a solid line connecting the actor's symbol to the use case oval, signifying direct interaction or communication between them. This notation, as specified in the UML standard, indicates that the actor either initiates the use case or participates in its execution, without implying any specific sequence or conditionality.[20] Semantically, the association conveys that instances of the actor can invoke or engage with the use case to achieve a system goal, modeling the structural link in behavioral terms rather than detailed flow. It is the simplest form of relationship in use case modeling, often bidirectional by default to reflect mutual communication, though an open arrowhead may be added at the use case end to denote unidirectional initiation by the actor if the interaction direction is explicitly constrained. Multiplicity can be annotated at the ends of the line (e.g., 1..* for multiple actor instances per use case), but basic associations typically omit such details unless needed for clarity.[15][20] For basic usage, no stereotypes such as <Include and Extend

In use case diagrams, the include and extend relationships enable the modularization of use cases by allowing common or optional behaviors to be factored out and reused, promoting clarity and reducing duplication in the model. These relationships are directed dependencies between use cases, distinct from associations with actors, and are essential for representing complex system interactions without inflating individual use case descriptions. The include relationship specifies that the behavior of one use case (the included use case) is inserted into another use case (the base use case), making the included behavior mandatory for the base to complete successfully. This is particularly useful for factoring out common subprocesses shared across multiple use cases, such as authentication steps that appear in various login scenarios. Semantically, the base use case depends on the included use case to execute its full behavior sequence, and the inclusion occurs at a specific point defined in the base use case's flow. The notation consists of a dashed arrow pointing from the base use case to the included use case, labeled with the stereotype <Generalization

In UML use case diagrams, generalization is a taxonomic relationship that enables inheritance between classifiers, specifically allowing one actor or use case to specialize another, forming an "is-a" hierarchy. This relationship is graphically represented by a solid line terminating in a hollow triangle arrowhead at the more general (parent) element, similar to generalization in class diagrams. For instance, a "VIP Customer" actor may generalize a "Customer" actor, indicating that the VIP Customer is a specialized type of Customer.[22] When applied to actors, generalization means the child actor inherits all associations and relationships of the parent actor, including connections to use cases. This inheritance allows the child actor to participate in all use cases associated with the parent without needing explicit links, promoting model reuse while maintaining clarity in roles. For example, if a "Customer" actor is associated with a "Place Order" use case, a specializing "Wholesale Customer" actor automatically inherits that association and may add further specializations. However, generalization between actors and use cases is not permitted, as it would violate the separation of concerns in the diagram.[13] For use cases, the generalization relationship indicates that the child use case inherits the behavior, properties, and associations of the parent use case, potentially refining or overriding aspects of that behavior to provide more specific functionality. The child use case thus represents a specialized variant, inheriting any actor associations from the parent. This supports abstraction by allowing common behaviors to be defined once in the parent and specialized as needed, such as a "Process Credit Card Payment" use case generalizing from a broader "Process Payment" use case. In practice, use case generalization is employed to model hierarchical refinements but is used judiciously, as overuse can introduce complexity and reduce the diagram's readability in simpler systems.[4][18]Notation

Graphical Symbols

The graphical symbols in use case diagrams, as defined in the official Object Management Group (OMG) Unified Modeling Language (UML) 2.5.1 specification, provide a standardized visual vocabulary for depicting actors, use cases, system boundaries, and relationships between them. These symbols ensure consistency and clarity in representing system interactions.[11][2] Actors are visually represented as a stick figure (the conventional and preferred form) or as a rectangle containing the actor's name with the stereotype <Diagram Conventions

In use case diagrams, layout follows established conventions to enhance readability. Actors are typically positioned on the left or right side outside the system boundary, while use cases are placed inside the rectangle to visualize the separation between external participants and system behaviors. Relationship lines should be drawn to minimize crossings and maintain an uncluttered appearance.[23][2] Naming conventions emphasize consistency and descriptiveness. Use cases are named with a verb-object structure starting with a strong action verb (e.g., "Process Order" or "Validate Payment") to indicate functionality. Actor names use descriptive nouns reflecting roles (e.g., "Customer" or "System Administrator"), with the first letter capitalized per UML classifier guidelines.[23][18] Stereotypes for relationships, such as <Development Process

Steps to Create

Creating a use case diagram follows a structured process derived from UML standards, beginning with requirements analysis and progressing to validation. This sequential approach ensures the diagram accurately captures the system's interactions with external entities without delving into implementation details.[2] Step 1: Identify actors from stakeholders and external systems. Actors represent entities outside the system boundary that interact with it, such as human users, other software systems, or hardware devices. Begin by reviewing project requirements, conducting stakeholder interviews, and analyzing system context to list potential actors; for instance, in an online banking system, actors might include "Customer" and "Bank Administrator." Prioritize primary actors who initiate interactions and secondary ones that support them. This identification establishes who drives the system's functionality.[26][4] Step 2: List main use cases based on user goals. Use cases encapsulate the system's observable behaviors or goals that actors aim to achieve, phrased as verb-noun pairs like "Withdraw Cash" or "Process Payment." Derive these from actor goals by brainstorming scenarios, functional requirements, and user stories, ensuring each use case provides value and remains at a high level of abstraction. Avoid decomposing into sub-steps here, as that belongs to textual use case descriptions. Aim for a focused set of primary use cases initially to maintain clarity.[18][16] Step 3: Draw the system boundary and place use cases inside. Represent the system as a rectangle labeled with its name, enclosing all use cases to delineate the scope of functionality. Position actors outside this boundary, typically on the left or as stick figures, to visually separate internal behaviors from external initiators. This step clarifies what the system does versus what it interfaces with, preventing scope creep.[2][27] Step 4: Add associations, then include, extend, and generalization relationships as needed. Draw solid lines connecting actors to relevant use cases to indicate direct interactions, specifying multiplicity if an actor participates in multiple instances. Subsequently, incorporate relationships among use cases: use dashed arrows for "include" (mandatory sub-use cases, e.g., authentication included in login) and "extend" (optional extensions, e.g., applying overdraft fees); employ generalization arrows for inheritance between actors or use cases. These elements, as defined in UML, refine the diagram without altering the core structure.[26] Step 5: Validate against requirements for completeness. Review the diagram by cross-checking against original requirements, ensuring all actors, use cases, and relationships align with stakeholder needs and cover edge cases without omissions or redundancies. Iterate with team feedback to confirm the diagram communicates the system's functional scope effectively; tools like traceability matrices can aid this verification. This final check upholds the diagram's role as a reliable requirements artifact.[28][29]Best Practices

To ensure clarity and maintainability in use case diagrams, practitioners should limit the number of use cases in a single diagram to avoid visual overload, typically keeping it focused and simple; for more complex systems, employ hierarchies through subsystems, packages, or multiple interconnected diagrams to organize content without sacrificing overview.[30][31] Use case diagrams must focus exclusively on external interactions between actors and the system, avoiding any depiction of internal implementation details, algorithms, or data flows, which could confuse stakeholders and shift attention from functional requirements to design concerns.[4][32] For enhanced precision and completeness, always pair use case diagrams with detailed textual descriptions of scenarios, including preconditions, postconditions, main success paths, and alternative flows, as the diagram serves primarily as a high-level visual summary while the narrative provides the substantive elaboration necessary for development and validation.[32][33] Iterative review is essential, involving stakeholders such as end-users, domain experts, and developers in regular validation sessions to refine the diagram, ensuring it accurately reflects intended behaviors and addresses ambiguities early in the process.[34][32] Generalization relationships should be applied judiciously, only when there is clear inheritance of behavior that adds meaningful abstraction and reuse—such as a specialized "VIP Customer Checkout" inheriting from a general "Customer Checkout"—to avoid unnecessary complexity that could obscure the primary functional structure.[2][30]Common Mistakes to Avoid

Several common errors in UML use case diagrams can lead to lower scores in academic grading or professional reviews, typically due to incorrect notation, lack of clarity, incomplete coverage of requirements, or violation of UML standards such as wrong arrow directions for include/extend relationships.- Focusing on internal system processes instead of user goals and interactions: Use cases should describe what the system does from the user's (actor's) perspective, emphasizing goals and interactions (the "what"), rather than internal mechanisms or processes (the "how"). This error shifts the diagram toward design or implementation details, undermining its role as a requirements tool and often resulting in deductions for lack of user-centric focus.[4]

-

Incorrect use of <

> and < : Examples include using <> relationships > for optional behavior (which should use < >) or < > for mandatory behavior (which should use < >), as well as incorrect arrow directions (include arrow points to the included use case; extend arrow points to the extending use case). Such mistakes violate UML conventions and commonly lead to grading penalties for improper notation.[30] - Naming use cases with implementation details or simple verbs instead of goal-oriented phrases: Using names like "Login" instead of "Authenticate User" or including technical details reduces clarity and fails to capture the user's goal. Use cases should be phrased as goal statements, typically verb-noun combinations from the actor's viewpoint.[31]

- Treating the system as an actor or including non-human actors incorrectly: The system itself cannot be an actor; actors are always external entities (human users or other systems) interacting with the system. Incorrectly including the system as an actor or misclassifying non-human entities confuses the diagram scope and boundaries.

- Overloading the diagram with too many use cases, relationships, or unnecessary details: Excessive elements cause visual clutter, reduce readability, and obscure key interactions. Diagrams should remain simple and focused, with decomposition handled via packages or multiple diagrams for complex systems.[30]

- Missing system boundary or not clearly identifying actors: Failing to draw the system boundary or clearly label and position actors outside it leads to ambiguity about scope and interactions, a frequent source of grading deductions.

- Confusing use cases with sequence diagrams or detailed flow of events: Use case diagrams provide a high-level overview of functionality and interactions, not detailed sequences, steps, or internal flows. This confusion results in inappropriate levels of detail and detracts from the diagram's purpose.