Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

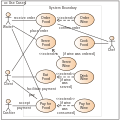

Component diagram

View on Wikipedia

| UML diagram types |

|---|

| Structural UML diagrams |

| Behavioral UML diagrams |

In Unified Modeling Language (UML), a component diagram[1] depicts how components are wired together to form larger components or software systems. They are used to illustrate the structure of arbitrarily complex systems.

Overview

[edit]A component diagram allows verification that a system's required functionality is acceptable. These diagrams are also used as a communication tool between the developer and stakeholders of the system. Programmers and developers use the diagrams to formalize a roadmap for the implementation, allowing for better decision-making about task assignment or needed skill improvements. System administrators can use component diagrams to plan ahead, using the view of the logical software components and their relationships on the system.[2]

Diagram elements

[edit]The component diagram extends the information given in a component notation element. One way of illustrating a component's provided and required interfaces is through a rectangular compartment attached to the component element.[3] Another accepted way of presenting the interfaces is the ball-and-socket graphic convention. A provided dependency from a component to an interface is illustrated with a solid line to the component using the interface from a "lollipop", or ball, labelled with the name of the interface. A required usage dependency from a component to an interface is illustrated by a half-circle, or "socket", labelled with the name of the interface, attached by a solid line to the component that requires this interface. Inherited interfaces may be shown with a lollipop, preceding the name label with a "caret symbol". To illustrate dependencies between the two, use a "solid line" with an "open arrowhead" joining the socket to the lollipop.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Components". Unified Modeling Language 2.5.1. OMG Document Number formal/2017-12-05. Object Management Group Standards Development Organization (OMG SDO). December 2017. p. 208.

- ^ Bell, Donald (December 15, 2004). "UML basics: The component diagram". IBM Developer. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- ^ Bell, Donald (December 15, 2004). "UML basics: The component diagram". IBM Developer. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2009) |

External links

[edit]

- "Components". Unified Modeling Language 2.5.1. OMG Document Number formal/2017-12-05. Object Management Group Standards Development Organization (OMG SDO). December 2017. p. 208.

Component diagram

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A component diagram is a type of structural diagram in the Unified Modeling Language (UML) that depicts the organization, dependencies, and interactions among software components in a system, with a primary focus on the physical aspects of implementation rather than abstract logical design. It illustrates how components are wired together to form larger assemblies or complete systems, emphasizing the modular breakdown of software into deployable units such as binaries, libraries, or executables.[2] In this context, a component is defined as a modular, replaceable part of a system that encapsulates its internal implementation details and exposes its functionality through well-defined interfaces, allowing for independent development, testing, and deployment. These interfaces serve as the entry points for interactions with other components, enabling loose coupling and promoting reusability across different environments.[2] Components can represent both logical groupings, such as business processes, and physical artifacts, like source code files or runtime executables, but the diagram prioritizes the latter to model real-world software assembly. Unlike logical diagrams such as class diagrams, which focus on the static structure of classes and their relationships in terms of inheritance and associations, component diagrams highlight runtime and deployment considerations, including how components are realized and distributed in execution environments.[2] This emphasis on physical software architecture aligns with the UML 2.5 standard, where component diagrams are specified to model the tangible building blocks of systems in component-based development.Purpose and Benefits

Component diagrams primarily serve to visualize the modularity of software systems, illustrating how independent units interact to achieve overall functionality while emphasizing the physical implementation aspects of object-oriented designs. They enable the identification of dependencies among components, which is crucial for planning integration and ensuring seamless assembly during development. By providing a static view of the system's structure, these diagrams support component-based development methodologies, such as those used in service-oriented architectures, and facilitate comprehensive architecture documentation for ongoing maintenance and evolution.[2][3][4] The use of component diagrams offers several key benefits in software engineering practices. They promote reusability by clearly delineating components as self-contained, modular units that can be deployed across multiple projects with minimal adaptation, thereby reducing redundant development efforts. Scalability is enhanced through the isolation of changes, allowing updates to individual components without propagating effects throughout the system, which supports growth in complex applications. These diagrams improve team collaboration by establishing explicit boundaries between modules, enabling parallel work by distributed development groups while maintaining a shared understanding of interdependencies. Additionally, they aid in risk assessment for large-scale systems by exposing potential integration points and failure modes early in the design phase.[5][6][7] In practical applications, component diagrams are instrumental in early architecture planning, where they outline the high-level decomposition of requirements into deployable units to guide subsequent design decisions. They prove effective in refactoring legacy systems, helping to dissect monolithic codebases into reusable components to enhance maintainability and extensibility. Furthermore, these diagrams contribute to compliance with international standards like ISO/IEC/IEEE 42010, which prescribes architecture description languages such as UML for capturing and analyzing system structures in a standardized manner.[8]Historical Development

Origins in UML

The component diagram was introduced as part of the Unified Modeling Language (UML) 1.0 specification, proposed to the Object Management Group (OMG) in January 1997 and formally adopted as UML 1.1 later that year. This addition addressed the growing needs of component-based software engineering, enabling modelers to visualize the physical organization and dependencies among modular, replaceable parts of a system, such as source code, binaries, or executables. Developed during the standardization efforts at Rational Software Corporation under OMG oversight, the diagram provided a standardized way to represent implementation-level architectures, filling a gap in earlier object-oriented notations that lacked explicit support for component modularity in large-scale systems.[9] The origins of the component diagram trace back to the unification of three prominent object-oriented modeling methods: the Booch method, which contributed concepts of modules and processes for structural decomposition; Object Modeling Technique (OMT), emphasizing class and object relationships extended to physical components; and Object-Oriented Software Engineering (OOSE), incorporating use-case-driven approaches to component interactions. These were integrated to form UML's foundational elements, with component modeling drawing further inspiration from industry standards like the Common Object Request Broker Architecture (CORBA) for distributed object interfaces and Microsoft's Component Object Model (COM) for reusable, binary-level components. This synthesis allowed UML to support interoperable, black-box views of software units, aligning with the era's shift toward distributed and enterprise-level development.[10][9] Key figures in this unification were Grady Booch, Ivar Jacobson, and James Rumbaugh—often called the "Three Amigos"—who led the efforts at Rational Software starting in 1994, merging their respective methods into a cohesive language by 1997. Their work focused on enabling component diagrams to model distributed systems, where components could encapsulate implementation details while exposing standardized interfaces, facilitating reuse across heterogeneous environments. This foundational role in UML emphasized scalability for complex, multi-vendor applications, reflecting the collaborative standardization process driven by OMG.[9] In its initial scope within UML 1.x, the component diagram emphasized black-box perspectives of components, prioritizing their external interfaces and dependencies over internal details to promote reuse in enterprise applications. This approach was particularly relevant amid the late 1990s software boom, when component-based development surged with technologies like CORBA and COM, demanding notations that could abstract large-scale systems for better maintainability and integration. The diagram thus served as a bridge between design and deployment, setting the stage for modeling physical software architectures in an increasingly modular computing landscape.[10]Evolution Across UML Versions

Component diagrams in the Unified Modeling Language (UML) have evolved progressively to address increasing complexities in software architecture modeling, with key refinements occurring across major version releases managed by the Object Management Group (OMG). During the UML 1.1 to 1.5 iterations (1998–2003), component diagrams incorporated refinements to support interfaces and dependencies, enabling better representation of modular interactions in response to the rise of web services and distributed systems. These enhancements allowed modelers to depict provided and required interfaces using compartment notations or delegation connectors, facilitating the visualization of service-oriented contracts without relying solely on class diagrams. These changes were particularly relevant for emerging technologies like SOAP-based web services, where profiles extended UML to map WSDL descriptions to component structures.[11] The UML 2.0 specification (2005) marked a substantial advancement by introducing ports and assembly connectors, which enhanced encapsulation and supported more precise protocol modeling between components. Ports act as interaction points on component boundaries, separating external interfaces from internal realizations, while assembly connectors explicitly link required and provided interfaces across components or their ports, promoting black-box reusability and reducing coupling in large-scale systems. This version also introduced the lollipop notation for provided interfaces and socket notation for required interfaces. This shift from UML 1.x's simpler dependency lines to these structured elements improved the diagram's ability to model runtime assemblies and deployment topologies. UML 2.5.1 (2017) further refined component diagrams through expanded support for profiles tailored to domain-specific languages (DSLs) and seamless integration with the Systems Modeling Language (SysML) for systems engineering applications. Profiles enable customization of component notation for specialized domains, such as embedded systems or real-time applications, while SysML's block definition diagrams build on UML components to incorporate hardware-software co-design elements like allocation relationships. These updates maintained backward compatibility but added semantic richness for interdisciplinary modeling, with no major syntactic overhauls to the core diagram elements. In recent years (2020–2025), OMG-sanctioned extensions and community-driven profiles have adapted component diagrams to contemporary paradigms like microservices and containerization, preserving the core syntax while extending stereotypes for concepts such as service boundaries, API gateways, and Docker/Kubernetes deployments. These adaptations ensure UML remains relevant for cloud-native architectures without mandating changes to the foundational metamodel.Key Elements

Components

In UML, a component is defined as a modular, replaceable part of a system that encapsulates its content and interacts through well-defined provided and required interfaces, allowing it to be substituted within its environment without affecting the overall system behavior. This abstraction promotes reusability and modularity, where components can represent physical implementation units such as JAR files in Java, DLLs in Windows environments, or executable binaries in various platforms.[12][6] Components possess key properties that facilitate their modeling and specification. Each component has a name for identification, often accompanied by a stereotype such as <Interfaces

In UML component diagrams, interfaces serve as the contractual boundaries that specify the services a component offers to or requires from its environment, defining sets of operations, signals, or data types without detailing their internal implementation.[13] This abstraction allows components to interact based on agreed-upon contracts, promoting modularity and independence in system design.[14] Provided interfaces represent the functionalities or services that a component exposes to other components or the external environment, enabling them to utilize these capabilities.[13] In notation, a provided interface is depicted using the "lollipop" symbol—a small circle attached to a line extending from the component's boundary—indicating what the component offers.[2] Conversely, required interfaces specify the external services or operations that a component depends on to fulfill its responsibilities, ensuring it can request necessary interactions from surrounding elements.[13] These are notated with the "socket" symbol—a semicircle resembling a receptacle attached to a line from the component—highlighting dependencies on the environment.[2] For more complex interactions, interfaces can be delegated through ports, which act as connection points on the component boundary to route provided or required services internally or externally.[13] This ball-and-socket notation facilitates clear visualization of how components wire together via compatible interfaces, without exposing implementation details.[15] The use of interfaces in component diagrams is essential for achieving loose coupling between components, as it enforces a contract-based design where changes to internal logic do not affect dependent elements, provided the interface remains stable.[13] This approach is particularly crucial in plug-and-play architectures, such as component-based development and service-oriented systems, where reusability and substitutability enhance system maintainability and scalability.[2]Ports

In UML component diagrams, ports serve as defined points of interaction on the boundary of a component or classifier, distinctly separating the internal implementation and behavior from external interactions with the environment or other components. As a specialization of Property, a port acts as a connectable element that enables controlled communication, typically typed by one or more interfaces to specify the nature of the interactions. This boundary mechanism ensures that external entities cannot directly access or manipulate the internal structure of the component, promoting encapsulation and modularity in system design.[1] Ports are categorized into two primary types based on their communication style: behavioral ports, which facilitate asynchronous signal-based interactions by delegating incoming requests directly to the owning classifier's behavior, and structural ports, which enable synchronous operation calls through explicit provided and required interfaces. Behavioral ports are denoted by setting the isBehavior attribute to true, allowing them to handle signals and reception operations without exposing service contracts. In contrast, structural ports, often configured as service ports with isService set to true, emphasize the provision and consumption of stable, synchronous services, supporting complex typing by multiple interfaces when needed.[1] Ports incorporate multiplicity to specify the number of instances they can instantiate, with a default of 1 but supporting ranges like 0..1 (optional single instance) or 0..* (multiple instances), and they exhibit directionality to manage data and control flows—provided interfaces for outgoing services (ball notation) and required interfaces for incoming dependencies (socket notation). Directionality can be unidirectional, bidirectional, or reversed via conjugated ports (where isConjugated is true), which invert provided and required roles to enable compatible connections between components. This flexibility allows ports to aggregate multiple interfaces, ensuring precise control over interaction flows.[1] The primary role of ports is to support delegation of provided and required interfaces, permitting composite components to route external requests—via assembly connectors—to internal parts, external entities, or the component's own behavior without revealing implementation details. This delegation mechanism enhances reusability and hierarchical composition, as internal structures remain hidden while external views remain consistent. Ports were introduced in UML 2.0 to explicitly model interaction protocols and enforce boundaries against direct internal access, with refinements in later versions like UML 2.5.1 improving support for protocol conformance and encapsulation in distributed systems.[1]Artifacts

In UML component diagrams, artifacts represent the physical entities that provide concrete implementations for abstract components, serving as tangible deployable units such as executable files (.exe), web application archives (.war), libraries (.dll or .jar), source code files, or documents. These elements embody the runtime manifestations of components, bridging the gap between logical design and actual system deployment.[1] The manifestation relationship defines how an artifact realizes a component, modeled as a specialized dependency stereotyped as <Relationships and Connectors

Dependency

In UML component diagrams, a dependency relationship represents a "uses" interaction where one component (the client) requires the services or elements provided by another component (the supplier) for its specification, implementation, or operation.[17] This directed relationship indicates that the client's behavior or structure relies on the supplier, but without implying a permanent or structural binding.[18] The notation for a dependency is a dashed arrow line extending from the client component to the supplier component, with the arrowhead pointing toward the dependee.[17] It may be optionally labeled with stereotypes such as<<use>> for general usage dependencies or <<import>> for package-level imports, enhancing clarity about the nature of the reliance.[18]

Dependencies in component diagrams can be categorized by their occurrence: compile-time dependencies, which involve static requirements like importing libraries during development (e.g., a component linking to a shared code module), and runtime dependencies, which manifest during execution such as dynamic loading of services.[17] These distinctions help model both design-time and operational needs without conflating them.[18]

Such relationships highlight potential fragility in the system architecture, as modifications to the supplier could necessitate changes in the client, underscoring the importance of stabilizing interfaces to minimize ripple effects.[17] For instance, in a web application, a frontend component might depend on a database access library for query operations, using a dashed arrow to denote this non-structural reliance.[18]

Assembly

Assembly connectors in UML component diagrams represent structural links between ports of components or parts, enabling the explicit wiring of required and provided interfaces to form composite structures. Specifically, an assembly connector defines that one or more parts provide services that other parts require, thereby realizing matches between conjugate interfaces—where a provided interface on one end aligns with a required interface on the other.[1] This mechanism supports the composition of subsystems by specifying communication or data flow between connected elements within a structured classifier, such as a component.[1] In notation, assembly connectors are depicted as solid lines connecting the ports of the involved parts, often incorporating ball-and-socket symbols to indicate the direction of interface provision (a circle for provided interfaces and a semicircle for required ones). Flow directions may be annotated with arrows to denote input or output, emphasizing the runtime interaction.[1] A filled diamond may appear at the assembly end to signify the connector's role in linking specific instances.[1] These connectors play a crucial role in component diagrams by illustrating how components collaborate at runtime to build assemblies or larger subsystems, contrasting with abstract dependencies by providing concrete structural composition. Constraints ensure compatibility: the connector must link ports whose effective required interfaces conform to the provided interfaces at the opposing ends, supporting both binary and n-ary connections while adhering to type conformance rules.[1] For advanced usage within composite components, assembly connectors integrate with delegation connectors, which route interactions from external ports to internal parts, further enabling hierarchical system assembly without exposing internal details.[1] This delegation supports the realization of external requirements through internal provisions, maintaining encapsulation in complex designs.[1]Realization

In UML component diagrams, the realization relationship denotes a specialized form of dependency where a component or classifier implements the specification defined by an interface or another component, thereby fulfilling a contract that ensures behavioral conformance and runtime substitutability.[19] This relationship specifies that the realizing element (client) provides the features and operations outlined in the realized element (supplier), without inheriting structure, and is essential for modeling how abstract specifications are concretely implemented in a system.[20] Unlike mere dependencies, realization implies a binding commitment to the contract, supporting model-driven development by linking high-level designs to executable artifacts.[19] The notation for realization consists of a dashed line terminating in a hollow (open) triangular arrowhead, directed from the realizing component toward the realized interface or component, often stereotyped as «realization».[20] This visual form distinguishes it from generalization (solid line with hollow triangle) by emphasizing implementation over inheritance.[19] For provided interfaces, an alternative lollipop notation—a circle attached to the component—may imply realization when connected via a dependency line, simplifying diagrams while conveying the same semantic intent.[20] Realization manifests in two primary types within component diagrams. Interface realization occurs when a component directly or indirectly provides the operations and signals specified by an interface, enabling the component to act as a supplier of that functionality; for instance, a component might realize a "Logger" interface to handle logging operations across the system.[19] Component realization, conversely, describes how a higher-level component is refined and implemented by subordinate classifiers, such as classes or other components, often detailed in a dedicated "realizations" compartment within the component's notation.[20] The importance of realization relationships lies in their role in establishing traceability from requirements and specifications to implementation, facilitating verification that components conform to defined contracts and aiding in system integration and maintenance.[19] For example, in an e-commerce system, a "PaymentProcessor" component might realize a "PaymentService" interface, ensuring it implements methods like processPayment() and refund(), thus guaranteeing interoperability with other components relying on that contract.[20] This traceability supports modular design principles, allowing independent development and testing of components while verifying overall system coherence.[19]Notation and Conventions

Symbols and Representations

In UML component diagrams, symbols provide a standardized visual notation to represent the physical and replaceable aspects of a system's architecture, as defined in the UML 2.5 specification. These graphical elements emphasize modularity, interfaces, and dependencies without prescribing implementation details. The core symbols include rectangles for components, lollipop and socket notations for interfaces, and specific line styles for connectors, enabling clear depiction of how components interact at a high level.[19] Components are depicted as classifier rectangles, typically with the stereotype<<component>> placed above the name or within guillemets. An optional iconic representation features a small rectangle in the top-right corner, or a legacy UML 1.x style with two protruding smaller rectangles on the left side, to distinguish them from other classifiers. These rectangles may include compartments listing provided and required interfaces, but the primary visual cue is the rectangle shape augmented by the icon for quick identification.[19][20]

Provided interfaces, which specify services offered by a component, are represented using the lollipop notation: a small circle (ball) attached to a line extending from the component, port, or directly from the component boundary, labeled with the interface name. Required interfaces, indicating services needed by the component, use the socket notation: a small semi-circle (receptacle) on the component or port, similarly labeled. These interface symbols attach directly to components for external views or to ports for more detailed internal structure.[19][21]

Ports serve as interaction points on component boundaries and are shown as small squares attached to the edges of the component rectangle, often labeled with a name and type (e.g., a tilde ~ for conjugated ports). They facilitate the connection of provided and required interfaces, acting as gateways without altering the core component shape.[19][20]

Connectors link components, ports, or interfaces and are rendered as lines with specific styles to denote relationship types. Assembly connectors, which represent runtime wiring between provided and required interfaces, use solid lines, potentially with ball-and-socket endpoints for clarity, and may include arrowheads to indicate direction if the connection is directional. Dependency relationships, such as usage or realization, employ dashed lines with open arrowheads pointing toward the depended-upon element; realization specifically uses a dashed line ending in a hollow triangle. These line conventions ensure directional flow is unambiguous.[19][21]

Artifacts, representing physical deployment units like files or executables, are symbolized as rectangles with the <<artifact>> stereotype and an optional document-like icon (a rectangle with a folded corner). They may appear nested within component shapes or connected via dependency lines to indicate manifestation.[19][20]

UML imposes no strict color conventions for component diagrams, allowing tool-dependent variations such as shading for compartments or color-coding for emphasis, but black-and-white line drawings remain the baseline for portability. Layout practices prioritize clarity, with related components often grouped within dashed rectangular frames (e.g., for subsystems or packages) to denote boundaries, though such frames are optional and derived from broader structured classifier notations. Stereotypes like <<component>> enhance these symbols semantically, as explored further in annotations.[19][21]

| Symbol | Description | Notation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Component | Rectangle with optional icon (two small rectangles) | <<component>> MyComponent (with top-right icon) |

| Provided Interface | Lollipop (circle on line) | Circle attached to boundary, labeled "IService" |

| Required Interface | Socket (semi-circle) | Semi-circle on boundary, labeled "IRequired" |

| Port | Small square on boundary | Square icon labeled "portName" |

| Assembly Connector | Solid line (optional ball/socket ends) | Line between ports with direction arrow if needed |

| Dependency Connector | Dashed line with open arrow | Dashed arrow from source to target |

| Artifact | Rectangle with document icon | <<artifact>> file.exe (folded corner icon) |

Stereotypes and Annotations

Stereotypes in UML serve as an extensibility mechanism to tailor the language for specific domains by extending the semantics of metaclasses, such as those used in component diagrams, without modifying the core UML metamodel. They are denoted by guillemets (e.g.,<<stereotypeName>>) and can be applied to components, interfaces, or connectors to convey additional properties or behaviors. Standard stereotypes from the UML specification for components include <<subsystem>>, which designates a component as a cohesive grouping of elements providing coherent functionality, and <<specification>>, which defines a component's interfaces without specifying its implementation.[1][12]

These stereotypes enhance component diagrams by clarifying roles and interactions. Custom stereotypes, such as <<microservice>>, extend this further for domain-specific modeling, like representing independently deployable services in distributed systems.[12] UML profiles, a feature of UML 2.x, organize sets of stereotypes, tagged values, and constraints into reusable packages for targeted applications, ensuring extensions remain backward-compatible with core UML.[1] For instance, the SoaML profile defines SOA-specific stereotypes like <<service>> for modeling service-oriented components and interfaces in enterprise architectures.[22]

Annotations complement stereotypes by adding explanatory or restrictive details to diagram elements. Notes appear as dog-eared rectangles connected by dashed lines, providing informal textual clarifications for components or relationships.[1] Constraints, denoted in braces (e.g., {reentrant}), impose formal conditions such as allowing concurrent invocations on a component's operations.[1] For more rigorous specifications, the Object Constraint Language (OCL) enables precise expressions of invariants, preconditions, or postconditions, such as verifying interface compatibility in a component assembly.[1]

Stereotypes and annotations collectively improve the precision and readability of component diagrams, aligning with OMG's emphasis on lightweight extensions that preserve UML's foundational structure, as outlined in the current specification.[23]

Creating Component Diagrams

Steps to Develop a Diagram

Developing a component diagram involves a systematic process that translates system requirements into a visual representation of modular components, their interfaces, and interactions. This methodology assumes prior familiarity with the system's functional and non-functional requirements, such as those derived from use cases or architectural documentation, ensuring the diagram remains traceable to implementation details like code modules or deployable units. The process emphasizes modularity and replaceability, aligning with the UML definition of components as classifiers that encapsulate system parts with specified interfaces.[1] Step 1: Identify system boundaries and major components from use cases or architecture docs. Begin by delineating the overall system scope to establish boundaries, distinguishing it from external entities. Review use case diagrams or high-level architecture documents to pinpoint major components, which may represent logical groupings (e.g., business logic modules) or physical elements (e.g., executable files). Components should be coarse-grained, replaceable units that encapsulate related functionality, avoiding overly fine details at this stage to maintain a high-level view of the system's structure. This step ensures the diagram captures the system's modular decomposition as per UML's structured classifier semantics.[1][2] Step 2: Define provided/required interfaces based on functional requirements. Analyze functional requirements to specify interfaces that components offer (provided) or depend on (required). Provided interfaces represent services or operations a component exposes to others, often modeled as contracts for incoming interactions, while required interfaces indicate dependencies on external services. Use the requirements to detail these interfaces with operations, signals, or data types, ensuring compatibility for inter-component communication. This definition supports UML's interface realization mechanism, where components conform to these specifications to enable loose coupling.[1][2] Step 3: Add ports and connect via assembly/dependency relationships. Introduce ports as explicit interaction points on component boundaries to mediate access to interfaces, distinguishing between external and internal connections. Connect components using assembly connectors for direct structural wiring between compatible ports or dependency relationships to denote usage without physical linkage. These relationships, as detailed in the UML specification, facilitate the representation of how components collaborate while hiding internal implementations. Limit connections to essential interactions to avoid cluttering the diagram.[1] Step 4: Incorporate artifacts for deployment mapping and validate against specifications. Map components to physical artifacts, such as source code files, binaries, or libraries, using manifestation relationships to indicate how abstract components realize concrete deployables. This step bridges design to deployment by associating artifacts with execution environments, though without detailing nodes (reserved for deployment diagrams). Validate the diagram against original specifications by checking interface conformance, relationship consistency, and boundary accuracy, ensuring no violations of UML constraints on component nesting or instantiation.[1][2] Step 5: Iterate with stakeholders, using tools for simulation or validation. Review the diagram with stakeholders, such as developers and architects, to gather feedback on completeness and clarity, refining elements like interfaces or connections as needed. Employ simulation or validation techniques to test interaction flows, confirming the diagram's alignment with system behavior. This iterative refinement promotes traceability, allowing mappings back to code artifacts for implementation guidance, in line with UML's emphasis on iterative modeling in component-based development.[1]Tools and Software

Several open-source tools facilitate the creation of component diagrams through accessible and customizable interfaces. PlantUML, a text-based diagramming tool, enables users to generate UML component diagrams using simple declarative syntax, supporting the visualization of components, interfaces, and dependencies without requiring graphical editing software.[24] It integrates seamlessly with documentation workflows, such as Markdown files, and is particularly valued for its version control compatibility via Git. yEd, developed by yWorks, offers free graphing capabilities with built-in UML stencil support, allowing users to drag-and-drop UML elements like components and assembly connectors to construct diagrams efficiently.[25] Commercial tools provide advanced functionality for enterprise-level UML modeling. Enterprise Architect from Sparx Systems supports the full UML 2.5 specification, including comprehensive component diagram features, and extends to the entire software lifecycle with capabilities like forward and reverse code engineering.[26][27] This tool excels in generating code from diagrams and importing existing source code to produce component models, making it suitable for large-scale projects requiring traceability and simulation. Cloud-based platforms emphasize collaboration and ease of access for distributed teams. Lucidchart provides UML templates specifically for component diagrams, enabling real-time co-editing and integration with tools like Google Workspace and Microsoft Office.[3] Similarly, Draw.io (now diagrams.net) offers free UML 2.5 shape libraries for component diagrams, with export options to various formats and support for embedding in wikis or Confluence.[5] These tools facilitate the steps outlined in diagram development by providing pre-built symbols and automated layout suggestions. Advanced features in modern tools enhance automation and integration. Many support CI/CD pipeline incorporation, such as PlantUML's GitHub Actions plugins that automatically render diagrams from source code commits during builds.[28] Visual Paradigm's 2025 edition introduces AI-assisted diagramming, where natural language prompts or code snippets guide the generation of component diagrams, including suggestions for relationships and validations against UML standards.[29][7] When selecting tools for component diagrams, key criteria include compliance with UML 2.5 for standardized notation, export capabilities to XMI for interoperability with other modeling environments, and reverse engineering from code to populate diagrams automatically.[4] Enterprise Architect and Visual Paradigm both offer robust XMI export and import, ensuring model portability.[30] Reverse engineering is prominent in tools like Enterprise Architect, which parses languages such as Java and C++ to derive component structures.[31]| Tool Category | Examples | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|

| Open-Source | PlantUML, yEd | Text-based simplicity, free UML stencils |

| Commercial | Enterprise Architect, Visual Paradigm | Full lifecycle support, AI assistance, code generation |

| Cloud-Based | Lucidchart, Draw.io | Collaborative editing, template libraries |

Examples and Applications

Simple System Example

To illustrate the core concepts of a component diagram, consider a simple e-commerce checkout system for a standalone application, comprising components for user interface (UI), business logic, and database access.[32] This scenario models the process of a customer adding items to a cart, processing payment, and updating inventory and orders, emphasizing modularity in a small-scale setup without distributed complexities.[32] In this diagram, the UI component, represented as the WebStore subsystem, provides the UserInterface through the Search Engine for product browsing and cart management. It requires the PaymentService (modeled as Manage Orders interface) from the business logic layer. The BusinessLogic component assembles internal elements like the Shopping Cart and Authentication via ports to connect with the Database component, which handles inventory and customer data through provided interfaces such as Search Inventory and Manage Customers.[32] Key relationships include a dependency from the BusinessLogic (Shopping Cart) to an external Logging library for transaction recording, and realizations where components like Orders realize the Manage Orders interface to fulfill contractual obligations. These connections use assembly connectors for internal composition within subsystems and delegation connectors for external interactions, ensuring loose coupling.[32] This example demonstrates modularity in a small-scale application by encapsulating four to five components—WebStore (UI and cart), Authentication, Warehouses (inventory database), and Accounting (orders database)—with basic provided/required interfaces and dependencies, allowing independent development and testing of each part.[32] For clarity, a textual representation of the diagram layout is shown below:+---------------+ +----------------+ +-------------+

| WebStore | | Warehouses | | Accounting |

| (UI Component)|<--req-| (Database) | | (Database) |

| | | | | |

| +----------+ | | +------------+ | | +---------+ |

| |Search | | | |Search | | | |Manage | |

| |Engine |prov User | |Inventory |prov | |Orders | |

| | |Interface | | |Search | | | |

| +----------+ | | +------------+ |Inv. | +---------+ |

| | | | | |

| +----------+ | | +------------+ | | +---------+ |

| |Shopping |req | |Manage | | | |Manage | |

| |Cart |Payment | |Inventory | | | |Customers| |

| | (Bus.Log)|Service | +------------+ | | | |realizes

| +----------+ | +----------------+ +---------+ |

| | dep. to Logging Lib. |

| +----------+ | |

| |Authenti-| | |

| |cation | | |

| +----------+ | |

+---------------+ |

+---------------+ +----------------+ +-------------+

| WebStore | | Warehouses | | Accounting |

| (UI Component)|<--req-| (Database) | | (Database) |

| | | | | |

| +----------+ | | +------------+ | | +---------+ |

| |Search | | | |Search | | | |Manage | |

| |Engine |prov User | |Inventory |prov | |Orders | |

| | |Interface | | |Search | | | |

| +----------+ | | +------------+ |Inv. | +---------+ |

| | | | | |

| +----------+ | | +------------+ | | +---------+ |

| |Shopping |req | |Manage | | | |Manage | |

| |Cart |Payment | |Inventory | | | |Customers| |

| | (Bus.Log)|Service | +------------+ | | | |realizes

| +----------+ | +----------------+ +---------+ |

| | dep. to Logging Lib. |

| +----------+ | |

| |Authenti-| | |

| |cation | | |

| +----------+ | |

+---------------+ |